2014-05-20 - 20 Years of Sales to IDITs

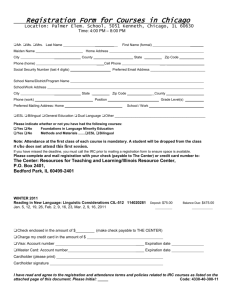

advertisement