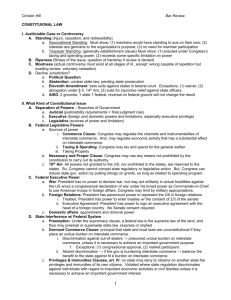

Con Law: State Power To Tax In Interstate Commerce

advertisement