Chapter 4: Foundations of Decision Making

advertisement

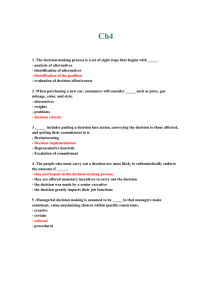

Chapter 4: Foundations of Decision Making Section 4.2 – What is Creative Potential? Key Terms Creativity Bounded rationality Heuristics Availability heuristic Representative heuristic Escalation of commitment Well-structured problems Ill-structured problems Programmed decision Procedure Rule Policy Summary Given that most people have the capacity to be at least moderately creative, what can individuals and organizations do to stimulate employee creativity? The best answer to this question lies in the three-component model of creativity based on an extensive body of research. This model proposes that individual creativity essentially requires expertise, creative-thinking skills, and intrinsic task motivation. Expertise is the foundation of all creative work. The potential creativity is enhanced when individuals have abilities, knowledge, proficiencies, and similar expertise in their fields of endeavor. Creative-thinking skills encompasses personality characteristics associated with creativity, the ability to use analogies, as well as the talent to see the familiar in a different light. On the other hand intrinsic task motivation is the desire to work on something because it is interesting, involving, exciting, satisfying, or personally challenging. This motivational component is what turns creativity potential into actual creative ideas. Most of us make decisions based on incomplete information. When we are faced with complex problems, most of us respond by reducing the problem to something we can readily understand. People often have limited abilities to process and assimilate massive amounts of information to reach an optimal solution, as a result, they satisfice. That is, they seek solutions that are satisfactory and sufficient–or just good enough. Numerous studies have added to our understanding of managerial decision-making. They suggest that decision making often veers from the logical, consistent, and systematic process that rationality implies. The process they follow is frequently referred to as bounded rationality. Because it is impossible for human beings to process and understand all the information necessary to meet the test of rationality, what they do is construct simplified models that extract the essential features from problems without capturing all of their complexities. Simon called this decision-making process bounded rationality. Under the definition of bounded rationality, decision makers can behave rationally (the rational decision-making model) within the limits of the simplified or bounded model. What are the implications of bounded rationality on the manager’s job? In situations in which the assumptions of perfect rationality do not apply (including many of the most important and far-reaching decisions that a manager makes), the details of the decisionmaking process are strongly influenced by the decision maker’s self-interest, the organization’s culture, internal politics, and power considerations. In order to avoid information overload, we rely on judgmental shortcuts called heuristics. Heuristics commonly exist in two forms–availability and representative. Both types create biases in a decision maker. Another bias is the decision maker’s tendency to escalate commitment to a failing course of action. Availability heuristic is the tendency to base judgments on information that is readily available. Representative heuristic causes individuals to match the likelihood of an occurrence with something that they are familiar with. Escalation of commitment is an increased commitment to a previous decision despite negative information. That is, the escalation of commitment represents the tendency to stay the course, despite negative data that suggest one should do otherwise. The types of problems managers face in decision-making situations often determine how a problem is treated. Some problems are straightforward. Such situations are called wellstructured problems. They align closely with the assumptions underlying perfect rationality. Many situations faced by managers, however, are ill-structured problems. They are new or unusual. Information about such problems is ambiguous or incomplete. Just as problems can be divided into two categories, so, too, can decisions. Programmed, or routine, decision making is the most efficient way to handle well-structured problems. However, when problems are ill structured, managers must rely on nonprogrammed decision making in order to develop unique solutions. Decisions are programmed to the extent that they are repetitive and routine and to the extent that a specific approach has been worked out for handling them. Programmed decision-making is relatively simple and tends to rely heavily on previous solutions. In many cases, programmed decision-making becomes decision making by precedent. A procedure is a series of interrelated sequential steps that a manager can use when responding to a well-structured problem. The only real difficulty is identifying the problem. A rule is an explicit statement that tells a manager what he or she ought–or ought not–to do. Rules are frequently used by managers who confront a well-structured problem because they are simple to follow and ensure consistency. A third guide for making programmed decisions is a policy. It provides guidelines to channel a manager’s thinking in a specific direction. Section Outline I. Why is Creativity Important in Decision Making? II. What is Creative Potential? III. The Real World: Modifications of the Rational Model A. What is bounded rationality? B. Are common errors committed in the decision-making process? IV. Decision-Making: A Contingency Approach A. How do problems differ? B. How does a manager make programmed decisions?