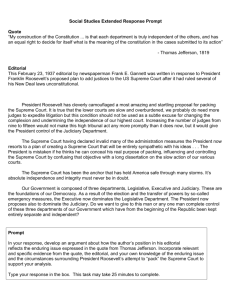

LEARNING STATIONS: SUPREME COURT CASES This activity will

advertisement

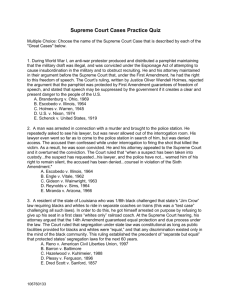

LEARNING STATIONS: SUPREME COURT CASES This activity will enable students to recognize landmark Supreme Court cases. It is assumed that the students will have a general knowledge of LANDMARK U.S. Supreme Court Cases. Instructions: 1. Post the learning stations on the wall around the room. 2. Assign students (individually or in small groups depending on class size) to go around the room to each station and read the cards. [Students can begin at any station and continue around the room until they return to their starting point.] 3. Students (or groups) should record the station number and determine the correct case described in the scenario along with their reason for their decision. [Groups should discuss their decisions and come to a consensus among members.] 4. After all students (groups) have completed the assignment, discuss the correct responses. Answers: Station 1 Station 2 Station 3 Station 4 Station 5 Station 6 Station 7 Station 8 Station 9 Station 10 Station 11 Station 12 Station 13 Station 14 Station 15 E. A. D. B. A. B. A. E. D. C. D. B. B. D. D. Schenck v. United States, 1919 Escobedo v. Illinois, 1964 Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896 Marbury v. Madison, 1803 Dred Scott v. Sanford, 1857 Gideon v. Wainwright, 1963 Reynolds v. Sims, 1964 Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824 Korematsu v. U.S., 1944 Engel v. Vitale, 1962 Miranda v. Arizona, 1966 McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 1978 Brown v. board of Education, 1954 Roe v. Wade, 1973 STATION 1 During World War I, an anti-war protestor produced and distributed a pamphlet maintaining that the military draft was illegal, and was convicted under the Espionage Act of attempting to cause insubordination in the military and to obstruct recruiting. He and his attorney maintained in their argument before the Supreme Court that, under the First Amendment, he had the right to this freedom of speech. The Court’s ruling, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, rejected the argument that the pamphlet was protected by First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech, and stated that speech may be suppressed by the government if it creates a clear and present danger to the people of the U.S. A. Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969 B. Escobedo v. Illinois, 1964 C. Holmes v. Warren, 1945 D. U.S. v. Nixon, 1974 E. Schenck v. United States, 1919 STATION 2 A man was arrested in connection with a murder and brought to the police station. He repeatedly asked to see his lawyer, but was never allowed out of the interrogation room. His lawyer even went so far as to come to the police station in search of him, but was denied access. The accused then confessed while under interrogation to firing the shot that killed the victim. As a result, he was soon convicted. He and his attorney appealed to the Supreme Court and it overturned the conviction. The Court ruled that “when a suspect has been taken into custody...the suspect has requested...his lawyer, and the police have not... warned him of his right to remain silent, the accused has been denied...counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment." A. Escobedo v. Illinois, 1964 B. Engle v. Vitale, 1962 C. Gideon v. Wainwright, 1963 D. Reynolds v. Sims, 1964 E. Miranda v. Arizona, 1966 STATION 3 A resident of the state of Louisiana who was 1/8th black challenged that state’s “Jim Crow” law requiring blacks and whites to ride in separate coaches on trains (this was a “test case” challenging all such laws). In order to do this, he got himself arrested on purpose by refusing to give up his seat in a first class “whites only” railroad coach. At the Supreme Court hearing, his attorney argued that the 14th Amendment guaranteed equal protection and due process under the law. The Court ruled that segregation under state law was constitutional as long as public facilities provided for blacks and whites were “equal,” and that any discrimination existed only in the mind of the black community. This ruling established the precedent of “separate but equal” that protected states’ segregation laws for the next 60 years. A. Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 1997 B. Barron v. Baltimore C. Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 1988 D. Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896 E. Dred Scott v. Sanford, 1857 STATION 4 First Supreme Court decision to declare an act of Congress unconstitutional; it established the Court’s power of “judicial review.” A president’s last-minute appointment of a political supporter as a federal judge was rejected by the newly-elected president, when the papers arrived after his inaugural. The appointee then sued to get his judgeship, to force the Secretary of State to give him his job. The power to force a president to give such commissions was granted by the Judiciary Act of 1789, part of which was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court; the appointee did not end up getting his federal judgeship. A. Barron v. Baltimore, 1833 B. Marbury v. Madison, 1803 C. Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824 D. Fletcher v. Peck, 1810 E. McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819 STATION 5 A slave from Missouri sued for his freedom, arguing that since his master traveled with him to “free” territories (in the old Northwest Territories where slavery was banned), he should have been released. The Supreme Court ruled that blacks, whether free or slave, could not become citizens because they were not considered citizens by Constitution; that Missouri Compromise’s ban against slavery in newly-gained territories was unconstitutional; and that slavery was a matter of state law and could not be protected or banned by either the Congress or the President. A. Dred Scott v. Sanford, 1857 B. Schenck v. United States, 1919 C. Barron v. Baltimore, 1833 D. Weeks v. United States, 1914 E. Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896 STATION 6 A drifter from Missouri was charged in Florida with breaking into a pool hall and stealing a small amount of cash and beverages. Denied a courtappointed attorney during his trial, he was convicted of felony burglary and sentenced to five years in prison. He wrote his own appeal to the Florida Supreme Court and later the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the trial court's refusal to appoint legal counsel for him denied him rights "guaranteed by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.” The Court agreed with the prisoner’s attorney’s statement that “the right to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours.” He was granted a new trial with a lawyer appointed for him, was found not guilty, and set free. Since that time, all states’ justice systems have provided attorneys for poor defendants. A. Stack v. Boyle, 1951 B. Gideon v. Wainwright, 1963 C. Feiner v. New York, 1951 D. Miranda v. Arizona, 1966 E. Denis v. United States, 1951 STATION 7 Numerous states had allowed an imbalance in the population of legislative districts to occur, usually resulting in urban (often ethnic minority) residents being under-represented in Congress and state legislatures. After hearing the case, the Court ruled that seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and in both houses of state legislatures must be apportioned on the basis of “one person, one vote.” In his written opinion for the majority, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote: "The right to vote freely for the candidate of one's choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government." A. Korematsu v. United States, 1944 B. Reynolds v. Sims, 1964 C. Roe v. Wade, 1973 D. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 1978 E. Gideon v. Wainright, 1963 STATION 8 Federal laws take priority over state laws in regulating commerce among and between the states, in this case involving a monopoly granted by the state of New York to a steamship company. The ruling by the Court established that the Constitution defines federal power to regulate commerce and no part of such power can be exercised by a state. Finally, the decision by the Court further established the supremacy of the national government over the states. A. Marbury v. Madison, 1803 B. Kramer v. Kramer, 1982 C. Munn v. Illinois, 1877 D. United States v. Nixon, 1974 E. Gibbons v. Ogden, 1824 STATION 9 This case centered around an American citizen of Japanese ancestry who was arrested and convicted for not reporting to a re-location center for Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II. He and his attorney argued that his civil rights had been violated, that the re-location program was not based on a reasonable fear of sabotage and/or espionage during wartime – that it was based on discrimination against a particular racial group, and thus was unconstitutional. The Court’s ruling sustained the legality of the order to re-locate this large groups of people (including the defendant), stating that the government’s actions were “an exercise of the power of the government to take steps necessary to prevent espionage and sabotage in an area threatened by Japanese attack…” A. Mineta v. Busch, 1942 B. Sulu v. Kirk, 1968 C. Gitlow v. New York, 1925 D. Korematsu v. U.S., 1944 E. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 1978 STATION 10 Public schools cannot require students to recite prayers. In New York, the state Board of Regents had prepared a "non-denominational" prayer for use in the public schools, trying to avoid anything that might offend one particular religious group or another. But in one school district a group of parents challenged the prayer as "contrary to the beliefs, religions, or religious practices of both themselves and their children." The state's highest court upheld the use of the prayer, on the grounds that state law did not force any student to join in the prayer over a parent's objections. The parents appealed. The Supreme Court of the United States ruled against state-sponsored prayers, stating that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment rests upon the belief that "a union of government and religion tends to destroy government and degrade religion." A. Wesberry v. Sanders, 1964 B. Reynolds v. Sims, 1964 C. Engel v. Vitale, 1962 D. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg County Schools, 1971 E. Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965 STATION 11 A man was arrested and taken directly to the police station. A victim of rape and kidnapping identified him as the perpetrator. The police then brought the accused into the interrogation room, questioned him for two hours, and received a signed confession. The police had never advised him of his right to an attorney or the fact that anything he said could be used against him in a court of law. The Court ruled that "the defendant's confession was inadmissible because he was not in any way [informed] of his right to council nor was his privilege against self-incrimination effectively protected in any other manner." He was granted a new trial, this time without use of the signed confession, and was again found guilty and sentenced to prison. A. Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965 B. Katz v. United States, 1967 C. Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969 D. Miranda v. Arizona, 1966 E. Reynolds v. Sims, 1964 STATION 12 This ruling by the Court allowed a broad interpretation of the Constitution in determining the federal government’s implied powers. The Chief Justice wrote, “The power to tax involves the power to destroy,” therefore states are not allowed under the Constitution to destroy the national government, and therefore they (states) would not be allowed the power to tax a branch of the Bank of the United States. A. U.S. v. Nixon, 1974 B. McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819 C. Brown v. Board of Education, 1954 D. Roe v. Wade, 1973 E. Marbury v. Madison, 1803 STATION 13 A medical student had twice been rejected by the medical school of his choice, even though he had a higher grade point average than a number of minority candidates who were admitted. He sued the university system, claiming “reverse discrimination.” As a result of the decision, he was admitted to the medical school and eventually graduated. This had a chilling effect on affirmative action in college admissions programs. Due to the Court’s ruling, race could be one of the factors considered in choosing a diverse student body in university admissions decisions, but the use of quotas in such affirmative action programs was not permissible. A. Cantwell v. Connecticut, 1940 B. Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 1978 C. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg County Schools, 1971 D. Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 1989 E. Cruzan v. Missouri Department of Health, 1990 STATION 14 An elementary student was refused admission to her neighborhood’s “white” elementary school because the local school district followed rules that segregated the races in different schools. A “test case” taken on by the NAACP attorneys, they charged that (in this case and ten others) segregated schools violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and against the practice of segregating public school students by race. The justices concluded that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place… separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” A. Engel v. Vitale, 1962 B. Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896 C. Ford v. Shevvy, 1906 D. Brown v. board of Education, 1954 E. Dred Scott v. Sanford, 1857 STATION 15 This case resulted in legalized abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy. The Court’s decision, based on the right of privacy, struck down dozens of state anti-abortion statutes. It was based on two cases that of an unmarried woman from Texas, where abortion was illegal unless the mother's life was at risk, and that of a poor, married mother of three from Georgia, where state law required permission for an abortion from a panel of doctors and hospital officials. While establishing the right to an abortion, this decision gave states the right to intervene in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy to protect the woman and the “potential” life of the unborn child. A. Furman v. Georgia, 1972 B. Mapp v. Ohio, 1961 C. Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 1989 D. Roe v. Wade, 1973 E. Cruzan v. Missouri Department of Health, 1990