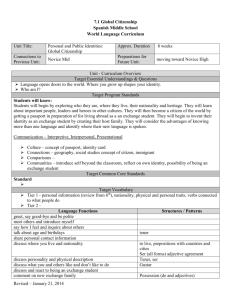

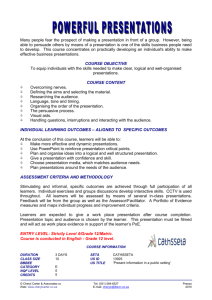

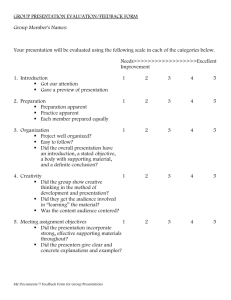

Developing Oral and Written Presentational Communication

advertisement