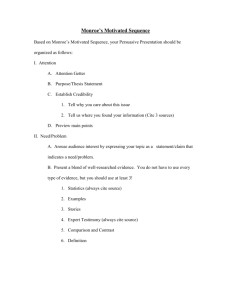

The Limits of Scrupling and the Adoption Act of 1729

advertisement

The Limits of Scrupling and the Adoption Act of 1729: A Brief Analysis of the PUP Task Force's Historical Problem By Toby Brown, Pastor, First Presbyterian Church, Cuero, Texas We Presbyterians suffer today from a terrible case of historical amnesia. Perhaps we caught this from our surrounding culture’s disdain of history and its preference instead for theatrics. We live in a sound-bite driven media culture that leaves little time for patient scholarship and rational discourse. Unfortunately, for such a historic faith, we Presbyterians are showing more and more the symptoms of this historical amnesia from which our nation suffers. We show these symptoms all too often: We quote selectively from our own historical documents and even our own confessions to prove a point. We don’t listen enough to all sides of an argument and we don’t take the time and effort to read the documents in question for ourselves. Instead, we turn to voices who offer quick and superficial readings of our history. Frequently these persons offer emotional appeals that ask us to “feel” at the expense of thinking through the consequences of the very ideas that we are being asked to adopt. Historical documents are often at least quoted as evidence, but too often, all that is really offered are proof-texts lifted up as summarizing entire arguments, while assertions in these same documents that would contradict the proffered analysis are ignored. Only in a historically challenged society, such as ours today, could this be done as frequently and brazenly as it is done these days. In these contentious times, with church unity fractured and our future together in question, we need to ask more of the Task Force than their present offering of a misleading reading of the Adopting Act of 1729. Standing in the historic stream of Presbyterianism in North America, we have the stated standards of Presbyterian polity and essentials that come from this document as an essential guide to our founding principles. Don’t we owe the church a better explanation of why we believe rather than misreading our history? If so, then at the very least, this explanation of our history should flow directly from our historical self-understanding and founding documents. The church deserves an accurate account of our history and our historical documents from our leaders, whether they agree with it or not. I read with disappointment the portion of the recent report of the Task Force on Peace Unity and Purity of the Church that offered a misleading summary of the intent and substance of the Adopting Act of 1729. To address this, I intend here to briefly analyze portions of the Task Force Report that bring up the historical reference to “scrupling” and its limits, as taken from the Adopting Act itself. The Task Force Report argues in a number of places that it is a historic principle of Presbyterianism to allow differences on “nonessential” points in our theology. They also assert that the Adopting Act can be cited to affirm the principle that each presbytery can be left free to determine what these points are. Here is one portion of the Task Force Report that makes this case (Line 716-736, italics mine): The tension between conscience and forbearance, on the one hand, and respect for the will of the whole body, on the other, has naturally occasioned the questions: What matters of belief and discipline are “essential and necessary” and, thus, require strict conformity, and where in such matters can latitude be permitted? As early as 1729, American Presbyterians faced these questions in relation to ministerial ordination. The then highest judicatory of the church, the synod, adopted the Westminster standards as its basis of faith and required all ministers to subscribe to them. This firmly established the American Presbyterian church as a confessional body with a single set of standards for faith and practice. The question of freedom of conscience under Scripture emerged immediately, however, because some ministers of the synod considered certain articles in the standards to be at variance with, or at least not explicitly enjoined by, Scripture. The synod resolved this conflict of conscience by permitting these ministers and, later, candidates for the ministry to declare their disagreements (“scruples”) with particular articles of the Westminster standards. It then delegated to the examining body the responsibility for determining whether the candidate’s disagreement concerned an essential article of the church’s “doctrine, worship or government.” Although the Adopting Act was later modified, it established a precedent that has heavily influenced American Presbyterians’ understanding of their confessional commitments to this day. Therefore, the church has consistently maintained that certain beliefs and practices are indispensable for the church’s theological integrity. At the same time, “differences always have existed and been allowed as to [the] modes of explaining and theorizing within the metes and bounds of the one accepted system.” So, we should ask, what were these “certain articles that were at variance with or at least not explicitly enjoined by, Scripture”? What of these “scruples” on which Presbyterians could differ from Westminster? Are there limits? Let’s go the cited document itself. Here is the relevant portion of the preliminaries of the Adopting Act itself (Italics mine): § 7. Act Preliminary to the Adopting Act. “And in case any Minister of this Synod, or any candidate for the ministry, shall have any scruple with respect to any article or articles of said Confession or Catechisms, he shall at the time of his making said declaration declare his sentiments to the Presbytery or Synod, who shall, notwithstanding, admit him to the exercise of the ministry within our bounds and to ministerial communion if the Synod or Presbytery shall judge his scruple or mistake to be only about articles not essential and necessary in doctrine, worship or government.” Scrupling then, was only allowed on articles that are deemed as “not essential”. The Task Force agrees with this point and there is no argument that the Adopting Act did hold all ministers to the essential articles of the Confession. But the point must then be asked: What are these essential and nonessential points and who defines them? What level of disagreement with Westminster was allowed? Were those essential and nonessential articles defined? Yes, they were! The Presbyteries were not left without guidance in these matters. The limits were set, upon how far we could agree to disagree on essential matters, as the next selection shows. Here is a portion of the actual Adopting Act of 1729: (italics and bold mine) § 8. The Adopting Act. "All the Ministers of this Synod now present, except one,…after proposing all the scruples that any of them had to make against any articles and expressions in the Confession of Faith and Larger and Shorter Catechisms of the Assembly of Divines at Westminster, have unanimously agreed in the solution of those scruples, and in declaring the said Confession and Catechisms to be the confession of their faith, excepting only some clauses in the twentieth and twenty-third chapters, concerning which clauses the Synod do unanimously declare, that they do not received those articles in any such sense as to suppose the civil magistrate hath a controlling power over Synods with respect to the exercise of their ministerial authority; or power to persecute any for their religion, or in any sense contrary to the Protestant succession to the throne of Great Britain.” The above quote shows clearly that the essential matters consisted of every part of the confession, except the selected chapters 20 and 23. The unity of faith and witness for these early American Presbyterians was agreed on every point, as outlined in Westminster, except as regards the role of the civil magistrate and church/state affairs. The limits of allowable differences were clearly defined in the Adopting Act for the ordaining bodies, be they Synods or Presbyteries. This Adopting Act can still be a clear model for the church, if we are willing to read it fairly and in its entirety. Clearly, in referencing the Adopting Act as justification for advocating Presbytery allowance on determining essentials each for itself, as they do later (albeit obliquely) argue in their Recommendation 5, the Task Force misrepresents the point of the Act itself. Presbyteries and Synods could only allow “scruples” up to a certain and designated point. This was seen as the basis for peace, unity and purity: a doctrine that was held in common by all the ordained officers of the newly organized Presbyterian Church. There is no room for making the argument that the Adopting Act leaves room for Presbyterians to define for themselves (individually or as Presbyteries) the essentials of the faith from the nonessentials. According to the Adopting Act and the earliest American Presbyterians, the church itself, as a corporate and unified body, decides what is essential and the church then has the duty of defining these essentials. If the Task Force wants to use our history or confessions to argue for a de facto Local Option on essential matters of faith and practice for ordination, as they do in Recommendation 5, then they should have looked elsewhere for support! The Adopting Act speaks for itself, if only we will take the time to listen.