Notes on Orientalism

advertisement

Edward Said: Brief Bio

Edward Said is a preeminent scholar and an important figure in

postcolonial studies. A professor of Comparative Literature at Columbia

University, he is also well known as an activist in Middle Eastern politics.

Said was born in Jerusalem, Palestine in 1935. His mother was of

Lebanese descent and his father was a successful Palestinian book

merchant. The family had homes in Palestine, Cairo, Egypt, and a

vacation home in Lebanon.

In 1948, while Said was a grade school student (at a private English

school in Cairo) the state of Israel was created and 80 percent of the

Palestinian population was left without a home. Said did not return to

Palestine until 1990.

Said was a privileged child and had little interest in the conflict between

Israel and Palestine. His educational life was one of private school wealth,

but perhaps most importantly, it was in a multi-ethnic, multi-religious

community.

In 1951, Said was expelled from Victoria College in Cairo for poor

behavior. Since his father had acquired American citizenship some years

earlier, Edward was also an American citizen. He was sent to the United

States and he finished high school at a private boarding school in New

England. Upon graduation he went to Princeton University and studied

English literature and history. He pursued his graduate studies at

Harvard. His Ph.D. dissertation was on Joseph Conrad.

The Suez Crisis made quite an impact on him as an Arab-Palestinian, but

now established in academic life in the U.S., he did not get involved in

politics of the situation. However, the Israeli victory over the Arab forces

in 1967, and the Israeli occupation of the last remaining Palestinian

territories, forced Said to take a political stance for the liberation of

Palestine. In 1968 he wrote his first article about the Palestinian cause:

"The Arab Portrayed."

In 1970 Said went to visit his family in Beirut, and while there got caught

up in the struggle for the liberation of Palestine. He became part of a

community of academics and writers who were involved in various

colonial and postcolonial struggles. During this time Said translated the

speeches of Yassir Arafat into English for the Western press. He became

an articulate voice for the liberation of Palestine in Europe and the U.S.

He remained independent and never affiliated with a political party.

However in 1977, Said was elected to the Palestinian National Congress in

exile.

Also during the 1970's Said, as an academic in the field of comparative

literature began writing on contemporary Arab literature; such authors as

Naguib Mahfouz, Elias Khouri, and the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

In 1975-1976 Said was a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study at

Stanford University. It was while he was at Stanford that he wrote

Orientalism. Over the next three years, he published Covering Islam

(1981) and The Question of Palestine (1979), which, in conjunction with

Orientalism, has been called his trilogy.

In the 1980's and 1990's Said effectively used his fame to further the

cause of Palestine and to advocate for human rights. In the 1980's Said

actively lobbied the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to re-think the

strategy of armed struggle toward liberation and urged Palestinians and

all Arabs to understand the importance of mutual respect and coexistence with Israelis. He advocated a two-state solution. As a temperate

voice, he made many friends within Israel.

During this period, Said became a target of personal attack by

conservative Jewish and Christian Zionists. These attacks on Said suggest

an "Orientalism" on the part of the right-wing Zionists. As an articulate

Arab intellectual, Said was viewed as a threat. In 1985 the Jewish

Defense League called him a "Nazi." A short time later his office at

Columbia was burned.

In 1991 Said resigned his position on the Palestinian National Congress,

and broke with Arafat. He was critical of the peace agreement between

Israel and the PLO made at Oslo, and felt that the PLO "lacked credibility

and moral authority."

The 1990's was a politically and personally difficult period for Said. In

1991 he was diagnosed with leukemia. The pain, suffering, and lengthy

hospitalization prompted him to write a memoir. Out of Place relates the

experiences of his youth and his feelings of exile. Said's illness went into

remission, but it still took a toll on his health and lifestyle. It was during

this period that he returned to Palestine for the first time since his

childhood.

In 1993 Said published his most comprehensive works on postcolonial

study, Culture and Imperialism, and in 1994, Representations of the

Intellectual. These two books, in his field of comparative literature,

brought him again into prominence in the academic community. Said

became the president of the Modern Language Association in 1998.

Despite his illness, Edward Said has continued to be an activist for the

peace, human rights and social justice. As his health permits, he travels

an international lecture route. He also writes a regular column for the

Egyptian newspaper al-Ahram, which appears in English and Arabic and

also online.

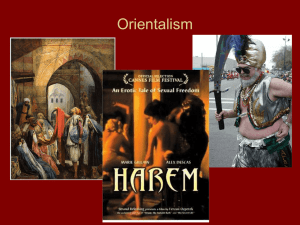

Introduction to Orientalism and Orientalism

Orientalism is:

“the study of Near and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, and peoples by

Western scholars.”

“the imitation or depiction of aspects of Eastern cultures in the West by writers,

designers and artists”

The former meaning has negative connotations because it refers to the study of the East by

Westerners shaped by the attitudes of the era of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th

centuries. It implies old-fashioned and prejudiced outsider interpretations of Eastern cultures

and peoples. This viewpoint was most famously articulated and propagated by Edward Said

in his controversial 1978 book Orientalism, which was critical of this scholarly tradition and

of a few modern scholars, including Princeton University professor Bernard Lewis.

Meaning of the term

Orientalism and Orient, derive from the Latin word oriens ("east", "rising [sun]"),

and, equally likely, from the Greek word ('h'oros', the direction of the rising sun).

"Orient" is the opposite of Occident. (Despite "Occident" being uncommon English

usage, both the "Orient" and "Occident" usages are current in French and Spanish.

Similar words are the French-derived Levant and Anatolia, deriving from the Greek

anatole, two further locutions denoting the direction from which the sun rises.)

The Terms

The Orient signifies a system of representations framed by political forces that brought the

Orient into Western learning, Western consciousness, and Western empire. The Orient exists

for the West, and is constructed by and in relation to the West. It is a mirror image of what is

inferior and alien ("Other") to the West.

Orientalism is "a manner of regularized (or Orientalized) writing, vision, and study,

dominated by imperatives, perspectives, and ideological biases ostensibly suited to the

Orient." It is the image of the 'Orient' expressed as an entire system of thought and

scholarship.

The Oriental is the person represented by such thinking. The man is depicted as feminine,

weak, yet strangely dangerous because he poses a threat to white, Western women. The

woman is both eager to be dominated and strikingly exotic. The Oriental is a single image, a

sweeping generalization, a stereotype that crosses countless cultural and national boundaries.

Latent Orientalism is the unconscious, untouchable certainty about what the Orient is. Its

basic content is static and unanimous. The Orient is seen as separate, eccentric, backward,

silently different, sensual, and passive. It has a tendency towards despotism and away from

progress. It displays feminine penetrability and supine malleability. Its progress and value are

judged in terms of, and in comparison to, the West, so it is always the Other, the conquerable,

and the inferior.

Manifest Orientalism is what is spoken and acted upon. It includes information and changes

in knowledge about the Orient as well as policy decisions founded in Orientalist thinking. It

is the expression in words and actions of Latent Orientalism.

Chronological implications of the Orient

In time, the common understanding of 'the Orient' has continually shifted East, as

Western explorers traveled farther in to Asia.

In terms of The Old World, Europe was considered The Occident (The West), and its

farthest-known extreme The Orient (The East).

In Biblical times, the Three Wise Men 'from the Orient' were actually Magi from "The

East", (relative to Judea), probably meaning the Persian Empire or Arabia. After a

period, as Europe learned of countries farther East, the defined limit of 'the Orient'

shifted eastwards, until reaching the Pacific Ocean, to what Occidentals (westerners)

knew as 'the Far East'.

Dating from the Roman Empire until the Middle Ages, what is now, in the West,

considered 'the Middle East' was then considered 'the Orient'. In that time, the

flourishing cultures of the Far East were unknown; likewise Europe was unknown in

and to the Far East.

In contemporary English, Oriental is usually synonymous for the peoples, cultures,

and goods from the parts of East Asia traditionally occupied by East Asians and

Southeast Asians racially categorised "Mongoloid". This excludes Indians, Arabs, and

the other West Asian peoples. In some parts of the United States, the term is

considered derogatory; for example, Washington state prohibits use of the word

"Oriental" in legislation and government documentation, preferring the word "Asian"

instead.

Earlier Orientalism

The first 'Orientalists' were 19th century scholars who translated the writings of 'the Orient'

into English, based on the assumption that a truly effective colonial conquest required

knowledge of the conquered peoples. This idea of knowledge as power is present throughout

Said's critique. By knowing the Orient, the West came to own it. The Orient became the

studied, the seen, the observed, the object; Orientalist scholars were the students, the seers,

the observers, the subject. The Orient was passive; the West was active.

One of the most significant constructions of Orientalist scholars is that of the Orient itself.

What is considered the Orient is a vast region, one that spreads across a myriad of cultures

and countries. It includes most of Asia as well as the Middle East. The depiction of this single

'Orient' which can be studied as a cohesive whole is one of the most powerful

accomplishments of Orientalist scholars. It essentializes an image of a prototypical Oriental-a biological inferior that is culturally backward, peculiar, and unchanging--to be depicted in

dominating and sexual terms. The discourse and visual imagery of Orientalism is laced with

notions of power and superiority, formulated initially to facilitate a colonizing mission on the

part of the West and perpetuated through a wide variety of discourses and policies. The

language is critical to the construction. The feminine and weak Orient awaits the dominance

of the West; it is a defenseless and unintelligent whole that exists for, and in terms of, its

Western counterpart. The importance of such a construction is that it creates a single subject

matter where none existed, a compilation of previously unspoken notions of the Other. Since

the notion of the Orient is created by the Orientalist, it exists solely for him or her. Its identity

is defined by the scholar who gives it life.

Contemporary Orientalism

Said argues that Orientalism can be found in current Western depictions of "Arab" cultures.

The depictions of "the Arab" as irrational, menacing, untrustworthy, anti-Western, dishonest,

and--perhaps most importantly--prototypical, are ideas into which Orientalist scholarship has

evolved. These notions are trusted as foundations for both ideologies and policies developed

by the Occident. Said writes: "The hold these instruments have on the mind is increased by

the institutions built around them. For every Orientalist, quite literally, there is a support

system of staggering power, considering the ephemerality of the myths that Orientalism

propagates. The system now culminates into the very institutions of the state. To write about

the Arab Oriental world, therefore, is to write with the authority of a nation, and not with the

affirmation of a strident ideology but with the unquestioning certainty of absolute truth

backed by absolute force." He continues, "One would find this kind of procedure less

objectionable as political propaganda--which is what it is, of course--were it not accompanied

by sermons on the objectivity, the fairness, the impartiality of a real historian, the implication

always being that Muslims and Arabs cannot be objective but that Orientalists. . .writing

about Muslims are, by definition, by training, by the mere fact of their Westernness. This is

the culmination of Orientalism as a dogma that not only degrades its subject matter but also

blinds its practitioners."

Edward Said and "Orientalism"

Said’s central ideas on “orientalism”

Knowledge about the East is generated not through actual facts, but through imagined

constructs that imagined "Eastern" societies as being all fundamentally similar, all

sharing crucial characteristics that are not possessed by "Western" societies.

This ‘a priori’ knowledge set up the East as the antithesis of the West.

Such knowledge is constructed through literary texts and historical records which are

often limited in terms of their understanding of the actualities of life in the Middle

East.

Before Said’s Orientalism:

"Oriental" was widely used to mean the opposite of "occidental" ('western'). The

comparisons were generally unfavorable to the former, but respected institutions like

the Oriental Institute of Chicago, the London School of Oriental and African Studies

or Università degli studi di Napoli L'Orientale, carried the term with no explicit

reproach.

After Said’s Orientalism:

The word "Orient" fell into disrepute after the word "Orientalism" was coined.

Following Michel Foucault, Said emphasized the relationship between power and

knowledge in scholarly and popular thinking, in particular regarding European views

of the Islamic Arab world. Said argued that Orient and Occident worked as

oppositional terms, so that the "Orient" was constructed as a negative inversion of

Western culture.

Had far-reaching implications beyond area studies in Middle East, to studies of

imperialist Western attitudes to India, China and elsewhere.

One of the foundational texts of postcolonial studies. Said later developed and

modified his ideas in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993).

Said puts forward several definitions of 'Orientalism' in the introduction to Orientalism. Some

of these have been more widely quoted and influential than others:

"A way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient's special place

in European Western experience." (p. 1)

"a style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made

between 'the Orient' and (most of the time) 'the Occident'." (p. 2)

"A Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient."

(p. 3)

"...particularly valuable as a sign of European-Atlantic power over the Orient than it is

as a veridic discourse about the Orient." (p. 6)

"A distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly, economic,

sociological, historical, and philological texts." (p. 12)

In his Preface to the 2003 edition of Orientalism, Said also warned against the "falsely

unifying rubrics that invent collective identities," citing such terms as "America," "The

West," and "Islam," which were leading to what he felt was a manufactured "clash of

civilisations."

Criticisms of Said

Historian Bernard Lewis:

Said's account contains many factual, methodological and conceptual errors.

Said ignores many genuine contributions to the study of Eastern cultures made by

Westerners during the Enlightenment and Victorian eras.

Said's theory does not explain why the French and English pursued the study of Islam

in the 16th and 17th centuries, long before they had any control or hope of control in

the Middle East.

Said has ignored the contributions of Italian, Dutch, and particularly the massive

contribution of German scholars.

Lewis argued that Orientalism arose from humanism, which was distinct from

Imperialist ideology, and sometimes in opposition to it. Orientalist study of Islam

arose from the rejection of religious dogma, and was an important spur to discovery

of alternative cultures.

Lewis criticised as "intellectual protectionism" the argument that only those within a

culture could usefully discuss it.

Said’s rebuttal:

must be placed into its proper context.

Lewis' critique of his thesis could hardly be judged in the disinterested, scholarly light

that Lewis would like to present himself, but must be understood in the proper

knowledge of (what Said claimed) was Lewis' own (often masked) neo-imperialist

proclivities, as displayed by the latter's political or quasi-political appointments and

pronouncements. Specifically, Lewis is aligned with prominent "think tanks" that

promote "neoconservative" views on U.S. Middle East Policy

Bryan Turner’s critique:

There were a multiplicity of forms and traditions of Orientalism.

Critical of Said’s attempt to try to place them all under the framework of the

orientalist tradition.

Other critics:

While many distortions and fantasies certainly existed, the notion of "the Orient" as a

negative mirror image of the West cannot be wholly true because attitudes to distinct

cultures diverged significantly.

a logical necessity that other cultures will be identified as "different", since otherwise

their distinctive characteristics would be invisible, and that the most striking

differences will hold up the mirror to the observing culture

the criticisms levied by Said at Orientalist scholars of being essentialist can in turn be

levied at him for the way in which he writes of the west as a hegemonic mass,

stereotyping its characteristics.

Orientalism: Summary

All discourse, particularly discourse about other cultures, is inherently ideological -regardless of the subject any historical discourse must be situated within a particular

framework whose overall structure is necessarily ideological -- Said situates his

argument in the realm of Orientalism, particularly the academic study and political

and literary discourse surrounding Arabs, Islam and the Middle East that originated

primarily in England and France and later the United States.

this discourse actually creates (rather than examines or describes) a palpable divide

between East and West -- this divide situates the West as a superior culture to the East

--This became politically useful for colonization

The discourse surrounding these countries is coded by a superiority that is not

necessarily reflected in the realities of the concerned countries. –Therefore the study

of someplace called the "Orient" and of some people known as "Arabs" fails to take

into account the reality of the area as being the same place as the West (i.e., part of

the Earth).

Said summarized his work in these terms:

"My contention is that Orientalism is fundamentally a political doctrine willed over

the Orient because the Orient was weaker than the West, which elided the Orient’s

difference with its weakness. . . . As a cultural apparatus Orientalism is all aggression,

activity, judgment, will-to-truth, and knowledge" (Orientalism, p. 204).

"My whole point about this system is not that it is a misrepresentation of some

Oriental essence — in which I do not for a moment believe — but that it operates as

representations usually do, for a purpose, according to a tendency, in a specific

historical, intellectual, and even economic setting" (p. 273).

On Orientalism

Principally a study of 19th-century literary discourse.

strongly influenced by the work of thinkers like Chomsky, Foucault and Gramsci,

engages contemporary realities and has clear political implications

Orientalism is often classed with postmodernist and postcolonial works that share

various degrees of skepticism about representation itself (although a few months

before he died, Said said he considers the book to be in the tradition of "humanistic

critique" and the Enlightenment).

The book is divided into three chapters:

The Scope of Orientalism

Orientalist Structures and Restructures

Orientalism Now

Chapter 1: The Scope of Orientalism

outlines his argument with several caveats as to how it may be flawed

It fails to include Russian Orientalism and explicitly excludes German Orientalism,.

Not all academic discourse in the West has to be Orientalist in its intent but much of it

is.

All cultures have a view of other cultures that may be exotic and harmless to some

extent, but when this view is taken by a militarily and economically dominant culture

against another it can lead to disastrous results.

Said draws on written and spoken historical commentary by such Western figures as

Arthur James Balfour, Napoleon, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Byron, Henry Kissinger,

Dante and others who all portray the "East" as being both "other" and "inferior."

He also draws on several European studies of the region by Orientalists including the

Bibliotheque Orientale by French author Barthélemy d'Herbelot de Molainville to

illustrate the depth of Orientalist discourse in European society and in their academic,

literary and political interiors.

One apt representation Said gives is a poem by Victor Hugo titled "Lui" written for

Napoleon:

By the Nile I find him once again.

Egypt shines with the fires of his dawn;

His imperial orb rises in the Orient.

Victor, enthusiast, bursting with achievements,

Prodigious, he stunned the land of prodigies.

The old sheikhs venerated the young and prudent emir.

The people dreaded his unprecedented arms;

Sublime, he appeared to the dazzled tribes

Like a Mahomet of the Occident. (Orientalism pg. 83)

Think: What notions of the Orient as ‘other’ do you find depicted here? How does the Orient

compare with the West?

Chapter 2: Orientalist Structures and Restructures

Outlines how Orientalist discourse was transferred from country to country and from

political leader to author.

This discourse was set up as a foundation for all (or most all) further study and

discourse of the Orient by the Occident.

"The four elements I have described - expansion, historical confrontation, sympathy,

classification - are the currents in eighteenth-century thought on whose presence the

specific intellectual and institutional structures of modern Orientalism depend” (120).

In 19th century European exploration by such historical figures as Sir Richard Francis

Burton and Chateaubriand, Said suggests that this new discourse about the Orient was

situated within the old one. Authors and scholars such as Edward William Lane, who

spent only two to three years in Egypt but came back with an entire book about them

(Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians) which was widely circulated and

read as truth throughout Europe, including by people like Burton who in turn based

their studies on all previous Western studies.

Further travelers and academics of the East depended on this discourse for their own

education, and so the Orientalist discourse of the West over the East was passed down

through European writers and politicians (and therefore through all Europe).

Chapter 3: Orientalism Now

Outlines where Orientalism has gone since the historical framework Said outlined in

previous chapters. (The book was written in 1978 and so only covers historical

occurrences that happened up to that date.)

Said suggests that the discovery of oil in the Arabian Peninsula and the shift in

regional power interests from England and France to the United States were important

events that shaped and reshaped Orientalist ideas.

Said suggests that the colonial mentality of the English and French perceptions of the

East shaped much of the United States' view of the region as well

Said also suggests that notions of the Orient were retranslated by people from the

region who had gone to the West to study. So for example a Saudi college student

studying in the US might return to Saudi Arabia with a retranslated notion about

himself that is situated within Western Orientalist discourse.

Said makes his overall statement about cultural discourse: "How does one represent

other cultures? What is another culture? Is the notion of a distinct culture (or race, or

religion, or civilization) a useful one, or does it always get involved either in selfcongratulation (when one discusses one's own) or hostility and aggression (when one

discusses the 'other')?" (325).

While there is much criticism centered on Said's book, the author himself repeatedly admits

his study's shortcomings both in this chapter, chapter 1 and in his introduction.

Influence

Orientalism is certainly Edward Said's most influential work and has been translated into at

least 36 languages. In October 2003, one month after Said died, a commentator wrote in a

Lebanese newspaper that through Orientalism "Said's critics agree with his admirers that he

has singlehandedly effected a revolution in Middle Eastern studies in the U.S." He cited a

critic who claimed since the publication of Orientalism "U.S. Middle Eastern Studies were

taken over by Edward Said's postcolonial studies paradigm" (Daily Star, October 20, 2003).

Even those who contest its conclusions and criticize its scholarship, like George P. Landow

of Brown University, call it "a major work."

However, Orientalism was not the first to produce criticism of Western knowledge of the

Orient and of Western scholarship: ‘Abd-al-Rahman al Jabarti, the Egyptian chronicler and a

witness to Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, for example, had no doubt that the

expedition was as much an epistemological as military conquest.’ Even in recent times (1963,

1969 & 1987) the writings and research of V.G. Kiernan, Bernard S. Cohn and Anwar Abdel

Malek traced the relations between European rule and representations.

Nevertheless, Orientalism is a detailed and influential work within the study of Orientalism

because, as Talal Asad argued, it is “not only a catalogue of Western prejudices about and

misrepresentations of Arabs and Muslims”, but more so an investigation and analysis of the

‘authoritative structure of Orientalist discourse – the closed, self-evident, self-confirming

character of that distinctive discourse which is reproduced again and again through scholarly

texts, travelogues, literary works of imagination, and the obiter dicta of public men [and

women] of affairs.’” Indeed, the book describes how ‘the hallowed image of the Orientalist as

an austere figure unconcerned with the world and immersed in the mystery of foreign scripts

and languages has acquired a dark hue as the murky business of ruling other peoples now

forms the essential and enabling background of his or her scholarship.’.

Criticism

In his book Dangerous Knowledge, British historian Robert Irwin criticizes Said's thesis that

throughout Europe’s history, “every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was a

racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.” Irwin points out that long before

notions like third-worldism and post-colonialism entered the academia, many Orientalists

were committed advocates for Arab and Islamic political causes. Goldziher backed the Urabi

revolt against foreign control of Egypt. The Cambridge Iranologist Edward Granville Browne

became a one-man lobby for Persian liberty during Iran’s constitutional revolution in the

early 20th century. Prince Leone Caetani, an Italian Islamicist, opposed his country’s

occupation of Libya, for which he was denounced as a “Turk.” And Massignon may have

been the first Frenchman to take up the Palestinian Arab cause.

George P. Landow is a professor of English and Art History at Brown University in the

United States. According to Landow, Orientalism certainly has had a great influence on

postcolonial theory since its publication in 1978. However, many questions have been raised

by Said’s manifesto.

Landow, in addition to finding Said's scholarship lacking, chides Said for ignoring the

non-Arab Asian countries, non-Western imperialism, the occidentalist ideas that abound

in East towards the Western, and gender issues in Orientalism.

Landow also finds Orientalism's political focus harmful to students of literature since it

has led to the political study of literature at the expense of philological, literary, and

rhetorical issues.

Landow points out that Said’s arguments are made by focusing only on the Middle East

and completely ignore China, Japan, and South East Asia. While Said criticises the

West’s homogenisation of the East, he himself generalizes “the orient” by limiting his

debate to one specific region.

Said failed to capture the essence of the Middle East, not least by overlooking important

works by Egyptian and Arabic scholars.

In addition to poor knowledge about the history of European and non-European

imperialism, another of Landow’s criticisms is that Said sees only the influence of the

West on the East in colonialism. Landow argues that these influences were not simply

one-way, but cross-cultural, and that Said fails to take into account other societies or

factors within the East.

One of the principal claims made by Landow is that Said did not allow the views of other

scholars to feature in his analysis; therefore, he committed “the greatest single scholarly

sin” in Orientalism.

Other critics discuss Said’s background when considering his point of view and his ability to

give a balanced academic assessment of Orientalism. Edward Said was born in the British

Mandate of Palestine to a wealthy family who sent him to the Anglican school of St George

in Jerusalem then to Victoria College in Cairo which Said himself referred to as “designed by

the British to bring up a generation of Arabs with natural ties to Britain”. After studying at

Victoria College he went to live in America at the age of 15 and then went on to study at

numerous academic institutions, and critics cite this as placing him outside the issues he

writes about in his book. Edward Said had an exceptionally privileged upbringing from a

financial perspective financed by his father whom Said described as “overbearing and

uncommunicative” in his book “Out of Place” (1999). This upbringing would place Said in

the “system” that forms much of the focus of his book and which depicts Orientalism as

facilitator of British and French white man's burden in the Arab world.

Bernard Lewis, in his publication Islam and the West, highlights what he considers to be

many historical and ethical errors and omissions from Said’s book and also highlights the

political undertones, citing examples of imperialist administrators' publications being

referenced as Orientalist academic work to portray Said’s hypotheses. Lewis also goes on to

summarize why he feels that Said’s work is so popular:

“There is, as anyone who has browsed a college bookshop knows, a broad market for

simplified versions of complex problems.”

Some of the points that Lewis cited in his criticism:

The isolation of Arabic studies from both their historical and philological contexts. (Said

dates the main development of Arabic studies in Britain and France and dates them after

the British French expansion)

Said's transmutation of events to fit his thesis (for example he claimed that Britain and

France dominated the eastern Mediterranean from about the end of seventeenth century,

knowing that at that time the British and French merchants and travelers could visit the

Arab lands only by permission of the sultan). (p109)

Many leading figures of British and French Arabists and Islamists who are the ostensible

subject of his study are not mentioned, such as Claude Cahen, Henri Corbin, Marius

Canard.

Said's neglecting of Arab scholarship and other writings.

Lewis and other critics of Said’s work feel that omissions and inaccuracies are an attempt by

the author to convey his “attitude” and feelings on Orientalism as academic study to underpin

his personal beliefs and causes.

(Abridged from Wikipedia)