Corps I

advertisement

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6

Types of Business Associations ................................................................................................................ 6

(a) Sole Proprietorships .......................................................................................................................................... 6

(b) Partnerships ...................................................................................................................................................... 6

History ................................................................................................................................................................ 7

Definition of Partnership .................................................................................................................................... 8

Conduct of the Business of the Partnership ....................................................................................................... 8

(c) Joint Ventures .................................................................................................................................................... 8

(d) Limited Partnership ........................................................................................................................................... 9

(e) Limited Liability Partnership .............................................................................................................................10

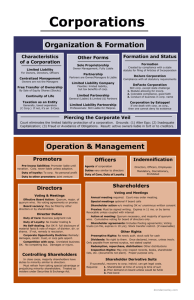

(f) Corporations .....................................................................................................................................................11

Differences b/w partnerships & corporations: ..................................................................................................11

2. Canadian Business Corporations ............................................................................................. 13

History ..................................................................................................................................................... 13

Four Incentives for Incorporation ......................................................................................................................13

Constitutional Basis for Incorporation ................................................................................................. 13

Incorporation and its Consequences ..................................................................................................... 14

BCBCA s.3, 10, 13, 17, 18, 30, 87 .......................................................................................................................14

3. The Corporate Entity ................................................................................................................. 15

(a) Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 15

Salomon v. Salomon & Co. [1897] A.C. 22 (H.L.) ...............................................................................................15

BCA ss.19, 17(2), 64, 121, 136 ...........................................................................................................................15

Lee v. Lee’s Air Farming (1961 J.C.) ...................................................................................................................16

Kosmopolous v. Const. Ins. Co. (1983) Ont CA (REEXAMINE)............................................................................16

Categories of Companies in Canada ..................................................................................................................17

(b) Lifting the Corporate Veil ............................................................................................................... 17

BCBCA, ss. 422 and 423: Dissolutions and cancellations of registration by registrar ......................................17

Clarkson Co. Ltd. v. Zhelka 64 D.L.R. 2d 457 (H.C.) ............................................................................................18

De Salaberry Realties Ltd. v. M.N.R. (1974) 46 D.L.R. (3d) 100 ........................................................................18

Guilford Motors v. Holmes ................................................................................................................................18

Walkowsky v. Carlton [p.138] (1966) 223 N.E. (2d) 6 (N.Y.C.A.)........................................................................19

4. Procedures of Incorporation ..................................................................................................... 20

(a) Place of incorporation ...................................................................................................................... 20

(b) Extra-provincial Licensing .............................................................................................................. 20

BCA ss.1, 374-399 ..............................................................................................................................................20

(c) Continuance ....................................................................................................................................... 22

(d) Widely Held and Closely Held Corporations ................................................................................. 22

Rothstein Purina case ....................................................................................................................................23

(e) Different Classification of Corporations (terminology unique to Canada) ................................. 23

(1) Special Act Corporation / Company [s.1 definition, s.4(1)] ..........................................................................23

(2) One-person Corporation [s.172(3), 140(4)] .................................................................................................23

(3) Constrained Corporation - Constrained by a combination of legislation and self-regulation (to meet

legislation) .........................................................................................................................................................24

(f) Incorporation Techniques................................................................................................................. 24

Two sources of incorporation in Canada: ..........................................................................................................24

(1) “Registration jurisdictions” i.e. BC, AB, Maritimes ...................................................................................24

1

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

(2) “Letters Patent jurisdictions” - Incl’s CBCA, OntBCA, QueBCA .................................................................25

(g) Registrar’s Discretion over Corporate Names [ss. 21-29] ............................................................. 25

5. The Nature of the Corporate Constitution ............................................................................... 26

(a) Generally ........................................................................................................................................... 26

BCA, ss. 10-19 See s.1 definition “articles” ........................................................................................................26

(b) The Concept of Restrictions/Alteration of Corporate Constitution ............................................. 26

Common Law .........................................................................................................................................................26

BCA, ss. 30-33, 154(1)(a), 228(3)(c), 259, 260, 378(2)/(4) .....................................................................................26

Remedies for Restricted Acts ................................................................................................................................27

Altering the Corporate Constitution ......................................................................................................................27

6. Pre-Incorporation Contracts ..................................................................................................... 28

(a) Common Law .................................................................................................................................... 28

Kelner v. Baxter (1866) ......................................................................................................................................28

Black v. Smallwood (1966) (H.C.A.) ...................................................................................................................28

*Heinhuis v. Blacksheep Charter Ltd. (1988) 46 D.L.R. (4th) 67, (B.C.C.A.) ........................................................29

(b) Statutory Reform – [s.20]................................................................................................................. 29

Problems with s. 20: ..............................................................................................................................................29

Landmark Inns of Canada Ltd. v. Horeak 1982 Sask QB ....................................................................................30

7. Management and Control of the Corporation .......................................................................... 31

(a) Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 31

Berle and Means (Managerial Model of Corporate Governance) .........................................................................31

Enter the Contractarians .......................................................................................................................................31

Mechanisms used by Owners for Controlling Agency Costs .................................................................................31

SH Voting, used in 2 ways: .................................................................................................................................31

SH Influences and Markets: ...............................................................................................................................31

Role of Corporate Law in Contractarian Model (Enabling) ....................................................................................32

Criticism of Contractarian Model ..........................................................................................................................32

B.C.C.A., ss. 1(3), 124, 135, 136 and 138 ...........................................................................................................32

(s.136) Vesting of Power in Board as a Whole.......................................................................................................33

Vesting subject to (s.301), (s.136) .....................................................................................................................33

Distinguish BC from Ont/Fed .............................................................................................................................33

Automatic Self-Cleansing Filter Syndicate v. Cunninghame (1906) ...................................................................33

Deadlock Theory / Residual Powers Theory ......................................................................................................34

Barron & Potter (p.176) IN CLASS EXAMPLE .....................................................................................................34

Two Ways in which Vesting of BOD Powers are Compromised in BC ...................................................................34

(b) Delegation .......................................................................................................................................... 34

(s.136): Director’s power to delegate ................................................................................................................35

(s.137): Power of Directors May Be Transferred ...............................................................................................35

(s.141): Officers May Be Appointed...................................................................................................................35

Montreal v. Champagne (1916) 33 DLR .............................................................................................................35

Hayes v. Canada-Atlantic Plant SS Co (1910) ....................................................................................................35

(c) Sale of Undertaking .......................................................................................................................... 36

BCA, s.301 – Power to Dispose of Undertaking .................................................................................................36

(d) Audit Committee (ss.223-226) ......................................................................................................... 36

8. Enforcement of Duties Owed by Directors and Officers to the Corporation (“Derivative

Action”) .......................................................................................................................................... 37

(a) Introduction – The Rule in “Foss v. Harbottle”............................................................................. 37

2

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

(s.142): Fiduciary Duties of directors are owed to the corporation, not to the shareholders. .........................37

Common Law: The Rule in Foss v. Harbottle .....................................................................................................37

Exceptions to the Foss v. Harbottle Rule (outlined in Edwards v. Halliwell) .........................................................38

Four Procedural Elements (from Foss and Harbottle and Statute, s.233) .............................................................38

Problems with the Common Law ..........................................................................................................................38

(b) The Statutory Derivative Action ..................................................................................................... 38

CBCA s.239 .........................................................................................................................................................38

BC BCA (s. 232) – Standing for Derivative Actions .............................................................................................39

BC BCA (s.233) Four Criteria for getting leave ...................................................................................................39

BC BCA (s.233(6)) Ratification............................................................................................................................39

Differences between CL and statute .................................................................................................................39

Re Northwest Forest Products 1975 BCSC ........................................................................................................40

Re Bellman and Western Approaches 1981 BCCA.............................................................................................40

Other Points re: Derivative Actions [AFTER LEAVE GRANTED] ..........................................................................41

(c) Costs (s.233(3)(b)) ............................................................................................................................. 41

9. Duties of Directors and Officers ............................................................................................... 42

(a) Care and Skill (Negligence) .............................................................................................................. 42

(i) Common Law .....................................................................................................................................................42

Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co. Ltd. (1925)................................................................................................42

A Changing Standard? .......................................................................................................................................43

(ii) Statutory Reform ..............................................................................................................................................43

BCA s.142: Duties of Directors and Officers – declaratory of the CL .................................................................43

BCA s.154: Director’s liability [personal] ...........................................................................................................43

BCA s.157: Limitations on Liability/Reliance [Defences]....................................................................................44

BCA s.228: Compliance or restraining orders ....................................................................................................44

People’s Dept Stores 2003 Que.CA....................................................................................................................44

Brandt investment v. Keep Rite 1991 OntCA .....................................................................................................44

(iii) Business judgment rule in Canada ..................................................................................................................45

(b) Fiduciary Duties................................................................................................................................ 45

BCA s.142(1)(a), (2), (3) .........................................................................................................................................45

(i) Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................45

(ii) Self-dealing / Contracting with the Corporation ..............................................................................................45

(a) Common Law ................................................................................................................................................46

Aberdeen Railway Co. v. Blaikie Bros. 1843-60 UKHL........................................................................................46

Gray v. New Augarita Porcupine Mines Ltd. 1952 UKPC ...................................................................................46

Northwest Transportation v. Beatty (p.528) .....................................................................................................47

NB: Common law was vague about what kind of contract ...........................................................................47

(B) Legislative Response ....................................................................................................................................47

BCA, ss.147 to 153 .........................................................................................................................................47

Differences b/w CL and statutory provisions: ...............................................................................................48

(iii) Corporate Opportunities .................................................................................................................................48

Cook & Deeks 1916 Ont.PC................................................................................................................................49

Regal (Hastings) v. Gulliver 1942 UKHL .............................................................................................................49

Peso Silver Mines Ltd. v. Cropper 1966 BCCA aff’d 1966 SCC ...........................................................................50

CURRENT COMMON LAW TEST .........................................................................................................................50

Canaero v. O’Malley 1973 SCC ..........................................................................................................................50

Approach in American jurisdictions ...................................................................................................................51

(iv) Competition .....................................................................................................................................................51

BCA, s.153: Disclosure of conflict of office or property .....................................................................................51

(v) Compensation ..................................................................................................................................................52

(vi) Hostile Takeover Bids and Defensive Management Tactics ............................................................................52

(A) Introduction .................................................................................................................................................52

3

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

(B) Common Law ...............................................................................................................................................53

Bonisteel v. Collis Leather Co.............................................................................................................................53

Hog v. Cramphorn Ltd [1967] Eng (mentioned in Teck v. Millar) ......................................................................53

***Teck Corp Ltd. v. Millar [1973] BCSC............................................................................................................53

On US Law ..........................................................................................................................................................54

(c) Relief From Liability for Breach of Fiduciary Duty ...................................................................... 54

(i) Ratification {s.233(6)} ........................................................................................................................................55

Northwest Transportation Company v. Beatty (1887) JCPC ..............................................................................55

(ii) Statute ..............................................................................................................................................................55

BCA, s.142(3): Waiver [virtually impossible]......................................................................................................55

BCA, ss.157, 234: Excuse – Breach of duty has occurred, but D is asking court not to hold them liable ..........55

(iii) Indemnification and Insurance (s.159-165):....................................................................................................56

10. Shareholders’ Rights ............................................................................................................... 57

(a) Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 57

Rights come from 4 sources: .............................................................................................................................57

(b) Voting Rights {s.173, 174} ................................................................................................................ 57

BCA, ss. 173-174: Voting, Shareholder Meetings ..............................................................................................57

(c) Shareholders’ Meetings {ss.166-186}............................................................................................... 57

1. Annual General Meeting (AGM), s.182 ..........................................................................................................58

2. Extraordinary/special general meeting, s.181 ...............................................................................................58

3. Court-ordered Meeting, s.186 .......................................................................................................................58

(i) Requisitioned Meetings and Shareholder Proposals (ss.167, 168, 187-191) ....................................................58

Requisitioned Meetings (ss. 167, 168)...............................................................................................................59

SH proposals (ss. 187-191) ................................................................................................................................59

Dow Chemical case (p.771) ...............................................................................................................................60

Jesuit Fathers case (p.772) ................................................................................................................................60

Greenpeace case (p.776) ...................................................................................................................................60

Air Industry Revitalization Co. v. Air Canada (1999) Ont.SCJ .............................................................................60

(ii) Removal of Directors, s.128(3) & (4), 131(a) ....................................................................................................60

11. Shareholders’ Remedies ......................................................................................................... 61

(a) Shareholder Agreements .................................................................................................................. 61

BCA, s. 175: Pooling Agreements.......................................................................................................................61

Voting Agreements (p.836) ...............................................................................................................................61

(i) Voting Trusts .............................................................................................................................................61

(ii) Buy/Sell Agreements ................................................................................................................................61

Dissent proceedings: s.237-246 (Appraisal Remedy) see below .......................................................................61

Unanimous Shareholder Agreement: (Ont. and Fed. only) LP jurisdictions ......................................................61

Two other ways to derogate from D’s powers: Delegation & Transfer of Powers ............................................62

Ringuet v. Bergeron 1960 SCC ...........................................................................................................................62

(b) The Personal Action: Standing to Sue (i.e. s.227, s.19).................................................................. 62

Farnham v. Fingold OCA ....................................................................................................................................62

Perlman v. Feldman (note on p. 897) ................................................................................................................63

Jones v. H.F Ahmanson (1969 CalSC) (p.906) ....................................................................................................63

GoldEx Mines Ltd. V.Revill (1975 OCA) ..............................................................................................................63

Bottom line (Farnam & GoldEx): ........................................................................................................................63

Beck, “The Shareholders’ Derivative Action” (p.885) ............................................................................................64

(c) The Statutory Oppression Remedy, s.227 (Complaints by SH) .................................................... 65

History ...................................................................................................................................................................65

Standing: s.227(1) ..................................................................................................................................................65

First Edmonton Place Ltd. v. 315888 Alberta Ltd (1988 AltaQB) .......................................................................65

4

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

Grounds for relief: s.227(2) ...................................................................................................................................66

Appropriate relief: .................................................................................................................................................66

Ferguson v. Imax Systems Corp. 1983 Ont.CA ..................................................................................................66

**Scottish Co-op Wholesale Soc. Ltd. v. Meyer 1959 UKHL ..............................................................................66

Ebrahimi v. Westbourne Galleries Ltd (p. 924) (1972) HL .................................................................................67

Diligenti v. RWMD Operations Kelowna (1976 BCSC) (p. 924) ..........................................................................67

Forms of relief & Orders: s.227(3) .........................................................................................................................68

Jackman case 1977 BCSC ...................................................................................................................................68

Relationship b/w Oppression Remedy and Derivative Action, p.940 ....................................................................68

(d) Other Statutory Remedies ............................................................................................................... 69

(i) Compliance and Restraining Orders and Rectification: ss.19(3), 228, and 229 ................................................69

Goldhar v. Quebec Manitou Mines Ltd. (1977 ON Div Ct) .................................................................................69

(ii) Dissent Proceedings (The Appraisal Remedy): ss.237-246 ...............................................................................69

Domglas v. Jarislowsky (1982 QCCA) (p.977).....................................................................................................70

Smeenk v. Dexleigh Corp. (1990 ON HC affirmed at CA 1993) ..........................................................................70

(iii) Winding-Up: s.324 ...........................................................................................................................................71

Ebrahimi v. Westbourne Galleries Ltd (1972 HL) ...............................................................................................72

In Re German Date Coffee Company (CA 1882) (p.989) ....................................................................................72

5

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

1. Introduction

Securities regulators are amoral – enabling people to incorporate and setting up the rules that govern.

Theoretically, you can incorporate anywhere (i.e. incorporate Vancouver corner grocery in PEI). Most likely

BC Business Corporations Act is the primary statute.

The alternative is to incorporate federally. The Federal Business Corporations Act; it is seen by some as

being more modern than the BC statute – also might be useful if you have a national presence.

BCA is difficult to navigate. There may be some provisions of FedBCA that don’t yet exist in the BC Act. BC

Act tends to be standalone…even recent amendments having perpetuated this ‘West Coast approach’.

Contrast to jursid’s like Australia and USA which have uniform (federal) governing statutes/bodies.

Types of Business Associations

(a) Sole Proprietorships

Sole proprietor: single person (of sufficient age to contract) doing business with no associates and without

being involved or accountable to any other person. (They can employ people, of course.)

One owner makes all decisions

Oldest & simplest form; Significant factor in CDN economy

No specific rules governing SP’s. There are rules that may apply depending on what kind of business the SP

is engaging in (i.e. Law Society Rules if SP lawyer, Competition Act rules, IP rules) – this is true throughout

the common law countries, but may not be so in civil law countries.

One of the main concerns is protecting the name of the business. Most prov’s but not BC have business

names protection statutes that enable SPs to register their biz name w/ the province and therefore gain

propriety over the name. May also be protected by CL tort of passing off.

Very common to use “& Associates” or such terms to give impression of bigger deal; however BC requires

such SPs using names that imply plurality that isn’t there to register the name. This gives the same/similar

protection as biz name registration schemes.

Easy to commence & dissolve (barring special munic., prov., or fed., licensing)

Enjoys none of the advantages of business corporations

Owner cannot separate business and personal life/finances; owner liable personally for all business

liabilities

(b) Partnerships

Two or more people carrying on business in common with a view to profit.

o ‘carrying on business’ connotes commercial but also connotes continuity…the wording of s.2

suggests that temporary endeavors (i.e. buying property to flip it) but the Act says that

Partnerships can be for a specific term. The law on this is unclear.

o ‘in common’ – does not mean (CL) that everyone is an active participant in the business. Although

most do, partnerships do not necessarily include all partners as active participants. (‘Active

partners’ and ‘passive partners’). Passive partners choose not to be involved in the day-to-day

running of the business.

Partners as agents –

o (a) They are agents of one another.

o (b) They are also fiduciaries of one another (BCBCA, s.22(1)). This protects (innocent) partners by

way of a claim of fiduciary duty. It also acts as an insurance policy against partners acting in such

a way that puts the other partners at risk.

o Having passive partners complicates things for a partnership b/c partnership contracts are agency

contracts. Every partner is an agent of another partner (every other partner) when that partner is

acting on behalf of the business. There is no such thing as the partnership as a legal person – only

the partners themselves are the legal persons.

NB: corporations as partners

o When suing a partnership, under BC Supreme Court Rules, you would style the cause as ‘Y v. X

carrying on as a firm’. ‘firm’ is a euphemism for partnership and ensures that all partners

(including those that may be unknown at the time) will be jointly and severally liable should the

lawsuit succeed.

6

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

Commercial profit motivation – this excludes clubs/societies/any form of un/incorporated non-profit

organization.

S.27 of the Partnership Act has default provisions for the sharing of profits (partners may vary by contract).

It can arise by the way people behave in relation to one another for a business purpose – no need for a

formal statement of partnership (contract).

Primarily arose b/c of disputes between partners or between partnerships and outsiders.

Great flexibility in designing internal management structure

Unlimited liability for partners jointly or jointly & severally

Legal personality for partnerships: although partnership is a legally recognized business entity, it is not a

separate legal person. The partnership is the people (incl. corporations) that make up the partnership.

o Merely being a partner does not make you an employee, however a partner can argue separately

that he/she is an employee.

Majority Rule: (under PA, s.27) If a majority of the partners agree on something, that is binding on the

minority partners; however the Act provides that there are certain fundamental matters that cannot be

dictated by majority rule. For example: changing the partnership agreement.

o However: the partnership agreement can vary this provision. Additionally, the Act provides that a

partnership

No dichotomy of ownership and control. If you are a partner, you have the same power and capacity

(subject to the partnership agreement) as the other partners.

o Some entitlement to profits from the business.

o Ongoing right to assert your power to manage the partnership.

o (Contrast to Corporation): dichotomy b/w ownership and control – Shareholders and directors

respectively. So shareholders have no agency toward the corporation, but they have claims to the

assets of the corporation based on percentage ownership. By contrast, the directors have to be

appointed/elected and have the powers to contract (powers of agency) on behalf of the

corporation.

Management of a partnership is a fairly specialized set of relationships. Same is true for a corporation, it is

just governed by a different set of rules.

o Is partner bound to perform managerial role? Statute says nothing, but Crane & Bromberg:

entitles other partner to seek dissolution where one partner is inherently incapable of performing

his part.

The End of a partnership:

o Section 33 - Partnerships dissolve whenever a partner dies or leaves the partnership. Most

partnership agreements therefore contain provisions for the partnership to immediately reform

as between the remaining partners.

o A corporation can only cease to be when a bureaucrat strikes its name from the registry.

o Great flexibility to commence & dissolve (only comply w/ Business Names Act and notify creditors

if one partner leaves)

Ways to avoid liability in partnership:

(a) Limited Partnership: A partner can limit his/her liability by becoming a Limited Partner, but must then

‘scrupulously avoid playing any part in the direction of the business.’ This has the requirement of statutory

registration (unlike regular partnership).

(b) Limited Liability Partnership: Partners avoid personal liability for negligence or other described wrongful

acts of a partner.

(c) Liability may also be avoided by creating partnership between business corporations. Technically, general

partner which is corporation is still liable, but if it has few assets then the result is limited liability.

History

1890 – British Parliament passed Partnership Act which became foundation for CDN partnership law.

Acts divided into:

o Nature of Partnership

o Relation of Partners to Persons dealing with them

o Relation of Partners to One Another

o Dissolution of Partnerships

7

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

o Miscellaneous

Act is not a complete code – equity & common law rules applicable to partnerships continue in force

except insofar as they are inconsistent with the Act.

Definition of Partnership

Conduct of the Business of the Partnership

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

Equality

Share equally in profit/loss, in managing the business.

Equal access to partnership books and in duty to render to each other true accounts and full

information of all things affecting the partnership. NB: contrast to distribution of power within

corporation (esp. right to participate in management)

Consensualism

Mutual rights & duties of partners may be varied by the consent of all the partners. Rule of

unanimity also governs admission of new partners and any changes in the fundamental character

of the partnership business.

One exception is that majority rules in ‘ordinary matters’. (maybe b/c unanimity would be

paralyzing? Efficiency!)

Fiduciary Character

Partners owe each other a fiduciary duty. Section 22(1) of BC Act: “A partner must act with the

utmost fairness and good faith towards the other members of the firm in the business of the

firm.”

Courts won’t budge or lower standard. Ever.

Personal Character of Partnership Contract

The statute (s.33) states that partnerships are automatically dissolved on death or insolvency of a

partner.

Although overall statutes make partnerships ‘unstable relationships’, a good partnership

agreement can ensure they are not.

(c) Joint Ventures

This may have legal meaning under certain statutory schemes (as do some other terms like conglomerate,

etc.) In Canada, debatable whether JVs are recognized.

Usually concerned with a single undertaking that doesn’t require continuous attention of every

participant. Ie: building/construction work – need pooled equipment/skill/expertise.

A JV is an association created by co-owners of a business undertaking, differing from partnership (if at all)

in having a more limited scope. In all important respects, the JV is treated as a partnership.

Never been unequivocally recognized in Canadian law. The reason there is a debate is because of

recognition in some US states: under American law (in some states) ‘if corporations could be involved in a

JV, their shareholders would be bound by the decisions of the BoD of the JV’. Some concern that the

shareholders should not be bound by directors who are not agents of the corporation.

US got around this by recognizing JVs as separate biz entity: (1) contribution by founders of

money/property/skill to the enterprise (2) some kind of sharing of the business (3) a right to mutually

control management (4) expectation of profit (5) objects of the venture are limited to a single undertaking.

(#1-4 are identical to that required of partnerships. In Canada, though, you can get a partnership that is of

limited duration.)

CANADA: Takeaway: no unequivocal recognition of JV as distinct biz enterprise by CDN courts – most

arrangements of this kind would constitute partnerships and therefore be governed by partnership law.

How do you decide which partnership law is applicable?

o Depends on the law that governs the contract of partnership

o Conflict of law rules apply “Proper Law of Contract” rule to say which jurisdiction is this

contract most connected with? This can be avoided by putting a choice of jurisdiction clause into

the contract (i.e. this contract is governed by the laws of NY)

8

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

Non-profits/Clubs: Non-business associations (used to be called ‘clubs’) are now also governed by many of

the same principles as corporations.

o In the common law, club members paid a membership fee and were only liable for the debts of

the club to the extent of their membership fee. At the same time, members were not entitled to

anything from the club. This parallels ownership in a corporation.

o In Canada most non-profit organizations are primarily concerned about their tax situation. So

almost universally in Canada, non-commercial organizations incorporate under the Society Act of

BC (is mirror image of BC BCA). This clarifies their non-commercial status (prima facie). Federal

Incorporation: if you do so you incorporate under provisions of Canada Corporations Act which

has been repealed (and replace by XX XX) except the parts which apply to non-profits.

(d) Limited Partnership

Introduced in CDN law around 1973 for capital-raising reasons

Definition: [s.50(2)] - a partnership that consists of one or more general partners and one or more limited

partners.

Limited Liability: The LP only enjoys this statutory privilege if they comply with Partnership Act. Liability is

limited to the moneys or property that they have already contributed or agreed to contribute [s.57]. They

are in the very same position as a shareholder in a CDN company. LP can lose its limited liability in certain

situations [ie. S.13(1) – lost if he takes part in the “control” of business]

Any partner who is not a limited partner is a general partner.

LPs are a way for entrepreneurs to gain investment by high-worth individuals who don’t have the

time/interest in running the company.

Advantages:

o Tax treatment can be attractive – profits of a LP can be subject to certain tax credits & deductions.

When a corporation earns a profit it is taxed directly (b/c corporation is separate legal

personality). The profits cannot be attached to the income of the shareholders. B/c LPs are not

legal persons, the profits (and losses) of a partnership are ascribed directly to the partners. The

rules are not quite as attractive as they once were, but there can still be advantages to a

partnership.

o Limited partner not expected (even prohibited) from taking part in management – this suits the

limited partner fine.

o Vendor avoids having to comply with the Securities Act. LPs usually don’t involve very many

people. Usually raising reasonable amount of money. If number of people is small enough (no

magic number) then LP doesn’t have to comply with the provincial Securities Act. If they are

forced to comply w/ Securities Act then they need to meet add’l requirements including

prospectus. Practical reasoning appears to be that ‘the rich can look after themselves’. If people

are wealthy enough to be investing in an LP, they likely have the financial resources to manage

their own risk.

o Transferability. A partnership is akin to a marriage: there is ‘emotional’ involvement on the

business side (who are they, how they behave, trust, etc.). However, a limited partnership doesn’t

impose these same concerns/restrictions on the limited partner. (i.e. if ltd partner decides to sell

LP rights it shouldn’t affect the GP(s) b/c LP can’t be involved in management. S. 18 gives a LP the

right to ASSIGN his interest, but assignee only has limited rights unless (a) all other partners

consent in writing to this assignment, or (b) the partnership agreement gives the assignor the

power. Act facilitates in s.51 and following.

Three formal requirements to establish a ltd partnership:

o (1) File Certificate: Fill out certificate (s.51) and file it with Registrar of Companies (in Victoria),

signed by all partners (general and limited). Announces certain characteristics (name of ptshp,

term of partnership, type of business, names & addresses of partners, their contributions

(including promised future contributions), entitlement to share of profits.

o (2) Name: must announce to the world that it’s a LP. End its name with “Limited Partnership” or

LP. If you fail to do this, the LPs can lose the protection of limited liability. If don’t comply, lose

privilege of limited liability (s.53).

9

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

o

(3) Not Managing: a LP is not liable as general partner unless he or she takes part in the

management/control of the business. [s.64].

More substantive, less formal requirement. This is sort of an estoppel theory – by acting

contrary to the partnership contract the LP loses protection of being a LP.

(1) Why should the statute mandate this? Look at 3rd party’s expectation: If LP is out

trying to sell things and acted as if they had role in management, can contractually bind

the P? If so, then LP may have participation in management. Management roles will

ordinarily involve in expectation on the outside that they are dealing with a GENERAL

partner (with unlimited liability). Since management involves hands-on involvement, LP

should have less opportunity to impose liability on the GPs.

(2) What is management? Test: What does T (outsider) reasonably think? If T thinks that

they are a partner is behaving towards them indicates that they are a general partner,

then that means that person is engaging in “management” so that partner loses their

“limited” liability. That person is estopped from shying away from liability.

Can you have a LP if a general partner is actually a LLcorp? Can individuals designate

themselves as LP and then incorporate themselves separately, then come back and be

the sole general partner?

See Notebook Sept 12 e.g. #1 – some courts have dealt with this by ‘lifting the veil of

incorporation’ while others have allowed this ‘device’ to remain. Paterson: best solution

is that if the arrangement appears to have been set up purely for the purpose of avoiding

liability (i.e. corporation has consistently had no assets and paid all profits through to

shareholders A&B) then the veil of incorporation should be lifted. *NB: this is likely to be

a problem mainly for smaller, unsecured creditors – they will not have spent the

time/money to investigate.

Advantages:

o Can combine advantage of LL with benefits of partnership tax treatment to avoid double taxation

(can be tax benefits)

o Not responsible for day-to-day management of business

o Not subject to Securities Act

Security: form of property right(s) in exchange for them giving money to someone else.

(See also ‘Securities Act’ for def’n.) Includes shares, partnership interest,

Securities Act is all about regulating businesses/businesspeople as they seek money from

unsophisticated investors.

o Transferability – can sell interest w/o permission of other partners [s.51-66]

Extraterritorial Scenarios: Where an LP/corp from another province comes and does business here: do

provinces have jurisdiction over ‘foreign’ LP?

o The BCA (corps) and Partnership Act (part dealing w/ LPs) [s.80] reporting requirements – if

“carrying on business,” the LP/corp must register with the registrar in Victoria. Why? Not to make

them submit themselves to BC regulations per se, but for the purposes of identifying themselves

to 3rd parties so we know who to serve process on (to sue them).

o BCSC has set out basis for its jurisdiction in the Court Rules.

o CL test for jurisdiction: presence. But LP/corp don’t have that physical ‘presence.’ So test if agents

for enterprise are carrying on business in BC, must register!

(e) Limited Liability Partnership

See summary of law in Canada pp.51-53. Did not exist in BC until January 2004.

American invention now present in most if not all CDN jurisdictions. Introduced in CDN law b/c lawyers &

accountants didn’t want to be liable for their crazy partnerships.

They address the problem of the liability of partners for the liabilities and debts of other partners:

o Esp. law firms, which were traditionally partnerships and where all partners wanted to be involved

in the management of the business.

o In respect of the liability of general partners as between one another, a single partner might incur

liability to a client. If that liability was upheld by courts (or agreed to) the client could turn to the

other partners for the amount.

10

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

LLPs create the opportunity for professionals to limit their liability to a portion of the amount that the

partner is held to be liable for.

Main provisions (not examinable): Section 94 - 113

o Partner not liable for ‘partnership obligation’ beyond their own debts and negligence liability.

o Definition of what they’re liable for varies with each statute across Canada.

o An attempt to prevent 3rd parties being able to hold OTHER partners beside A to share in certain

liabilities (debt and negligence).

BC: Amendment introduced (Part VI of Partnership Act) to work in conjunction with Legal Professions Act.

Possible for individual partnerships to incorporate. Most of them will register as LLP, even if they’ve

individually incorporated, to take advantage of limited liability.

(f) Corporations

Advantages

Corp has its own legal personality, separate from SH/D/O

Corp has perpetual succession and isn’t affected by any changes in, or deaths/retirements of its members.

Disadvantages

Incorporation must be sought from gov’t agency and requires filing of documents + adoption of a

corporate constitution.

Corp wishing to do business in more than one province will either have to incorporate federally or obtain

an extra-provincial license.

Corps are requires to hold meetings, elect directors, and provide SH with information.

Why wouldn’t a business incorporate?

Some professionals aren’t allowed to conduct business in an incorporated form (i.e. lawyers)

The promoters may only envisage a short-term business relationship (i.e. joint venture)

Partnerships are often formed between corporations

Unincorporated forms of business may offer tax advantages

Differences b/w partnerships & corporations:

(1) Corp is separate legal entity (unlike P) which are fictional (only exist through agents, employees that act

on the Cs behalf.)

o Partnership has no existence in law apart from its members (partners) and ceases to exist as a

partnership in law when one P leaves (unilateral breach of K).

o Lots of theories about corporate personality. A corps remains despite SH/D come and go, because

it’s fictional and can only act through human intermediaries (agents: directors, employees).

(2) Corp has formal steps for formation and dissolution; Partnerships can form by operation of law and

dissolve when a partner dies, retires, etc.

(3) Putting aside LPs, in all other partnerships, all partners can take part in the management of the

business.

o Partners have not only property rights but also right to act as partner and thereby bind your

partners (s.27). Even if they’re “passive investors” (only contribute capital and don’t take active

day-to-day role), they CAN, if called upon.

o In corporation there is an invitation for specialization. Must also have:

Shareholder(s) – ownership: owning something (property rights), also have right to vote

at shareholder meetings

Director(s) - [term of art] power: have the power to manage the company. (s 136) –

vesting of power, to the exclusion of SH.

o NB: In private/closely-held corps, has very few SH, and they’re likely all D. So separation between

ownership/control doesn’t really apply. This distinction more applicable to public/widely-held

corps, where have thousands of SH (investment in shares).

(3)Because partnership is contract, Privity is important – must be unanimity in any change of the business

of the partnership.

11

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

o

o

In a corporation, the directors make the decisions (s.136), not the shareholders.

2 restrictions to D’s power: (1) Company’s constitution can limit them and the type of business the

company is engaged in; amended via “special resolution” (vote). (2) If D tries to make a

“fundamental change in business,” triggers SH’s right to appraisal remedy (right to sell their

shares and exit the enterprise).

(4) Transferability of Ownership

o A Partner can’t transfer partnership interest without unanimous agreement between all Ps

(modification to terms of K); but in a Corp the shares are prima facie transferable.

o Public Corp – fellow SH don’t care who you transfer shares to, b/c can’t be involved in

management. Private Corp – care, so usually have “SH’s agreement” (think pre-nuptial). In private

corp, shares are “unattractive” because no independent market as for public corp, so difficult to

transfer. Why would they want to buy your shares if you want to get rid of them?

o CH companies actually want it to be difficult to transfer share ownership – the intimacy of a

closely held corporation is a key feature of them. So, most CH constitutions will have a clause

limiting the transfer – usually a preemptive right (first right of refusal).

(5) Publication of Trading Capital [value of assets contributing to enterprise when first est.]

o Whether public/private, when you incorporate, must publish its capital = statement of its

ownership in terms of a # of shares. [fractual ownership in terms of shares]

This is filed with the registrar. (i.e. ‘the capital of this company consists of 100 shares’.) It

is important to lawyers b/c it tells an outsider how many shares the company was

allowed to issue. Once the full number of shares has been issued, corporations can’t

issue more shares without amending their constitution.

o By contrast, partnerships do not have to say anything about their ownership to the outside world.

(6) Number of Members [no max # for both P/corp]

o Partnership requires at least 2 members. Could have more, but realistically difficult if too many (all

want to manage); generally only a few.

o Corps: can be ONE person, but can reach multinationals with millions of SHs. As # of SH increases

in a corp, the likelihood that it will be regulated by regimes outside the BCA also increases

[securities regulators].

How to become a shareholder (these apply to both private/public companies):

1. Subscription: Acquire shares upon the company’s incorporation. Ds have the power to issue those shares

upon the incorporation of the company.

2. Allotment: Issuing (unissued) shares after the company has already been incorporated (at some future

time). Sometimes Ds may not issue all the shares possible (under the company’s constitution) right away –

Ds may have power to issue additional shares at a future time.

3. Transfer: this is really just an ordinary sale of goods [stock exchange].

4. Transmission: person [executor of will, usually] becomes a shareholder on death of another, via operation

of law.

Shareholder v. member

SH is anyone who has acquired legal title to share(s).

Member – registered on member list; are SH who has right to vote at meetings.

NB: two types of shares in Canada:

Par-value – shares are described or defined in terms of a monetary amount. i.e. ‘authorized capital consists

of 100 shares of $1 each.’ Par value doesn’t represent value, but rather ownership/entitlement to

dividends, return of capital on winding up, etc.

No-par-value – shares include no monetary amount. i.e. ‘authrorized capital consists of 100 shares.’ This is

the favored approach because they don’t suggest the real value of the shares to anyone. So if you own 50

of shares in 100 share company, you own 50% of the value of the corporation. Contrast to Par-value where

$value doesn’t really tell you anything, although they seem to imply that they are worth x, though they

aren’t.

12

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

2. Canadian Business Corporations

History

Four Incentives for Incorporation

(1) Limited Liability

a. Privilege granted by state to SH of registered corps – s.87. Limit set by amount agreed to pay for

shares at subscription; not liable for anything beyond that.

b. Corps themselves don’t enjoy LL; they are fully liable to their creditors (secured/unsecured).

c. LL beneficial for SH of WH corps, because despite whatever craziness management undertakes,

they are only liable for the amount of the share (originally).

d. LL not beneficial for SH of CH corps. Creditors will find other means to secure the debts. It’s the

unsophisticated unsecure creditors who are at risk. In loans, will want signatures of all SHs too,

not just company.

e. There may be situations where limited liability is lost.

(2) Perpetual succession

a. Results because of the legal fiction of the corporation.

b. Huge advantage for WH corps, but not for CH corps, where there is a greater risk of all SH/D die at

same time. Then there’s no possibility for the SH to elect new D.

c. Personal representatives of deceased have all the rights of deceased members. So they may elect

replacements (s.115).

i. Who wants to become an owner in that situation? CH Corps would often have assets that

are unsaleable. What are the shares worth (in an open-market sense)?

ii. When advising CH corps, numerous measures can be taken to protect against this.

(3) Transferability

a. Shares can be bought/sold, but Ds are maintained, until voted in or out of office at AGM.

b. Not applicable to private companies – don’t really transfer shares much, and don’t want to, and

may go to lengths to prevent shares being acquired by outsiders.

c. But too much transfer? Questionable value of company, but generally go up and down.

d. But recently Cdn companies have been able to buy their own shares – part of a recent “going

private” phenomena, for investment purposes.

(4) Distinction between ownership + control

a. (1) SH (owners) attend AGMs vs. (2) BOD (management)

b. [s.136]– “The directors of a company must, subject to this act, regulations, and company

constitution…, manage or supervise and manage the affairs…” This means (through cases) that

management can do almost anything, including: issue shares, buy shares, distribute dividends (or

not), take the company into new endeavors.

c. Bad for CH Corps?

i. These two overlap. Most of SH will often be the Ds too.

ii. Also, minority SH: if each of 3 people own 1/3 of the shares, any one of them is at risk of

being outvoted at any time. A minority shareholder in a corporation is often in a risky

place b/c they are always potentially on the losing end of the votes. They also have no (or

a very difficult) parachute-out option because where will they sell their shares?

Constitutional Basis for Incorporation

[See pp.62-63]

Parallel authority to incorporate both federally or provincially:

(1) s.92(11) – provinces have power in relation to companies with “provincial objects.”

o Bonanza Creek – “provincial objects” not limited to those heads listed under s.92. No limits based on

subject matter or even geography as to what a provincially-incorporated company can do. So a BC

corps can carry on business throughout Canada and other countries, and can carry on lines of business

that are within s.91, if extra-provincial jurisdiction will allow it.

o So “provincial objects” language largely neutralized by the SCC.

13

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

(2) s.91 POGG

o Parsons/Multiple Access – not just residual power (if not “provincial object”); Feds can incorporate

business to carry on business anywhere.

So what’s the difference? You either like the prov/fed Act better. Although some differences still exist in Acts,

practically no effects.

So WHERE do corps incorporate? Federal? Provincial – which province?

o (1) Custom-made facilitate what you want to do better in Fed over Prov, for example.

o (2) Status Federally if you want that “national presence” or connotes “nation-wide,” which doesn’t

mean that they are, but just gives that impression.

o (3) More name protection for a federal company

o (4) The major difference constitutionally is:

Federally there are articles of incorporation + bylaws

Provincially there are notice of articles + articles

o (5) Geographical convenience if Fed-regulated, would probably need more lawyers in Ottawa to

deal with the fed regulations.

Jurisdiction

o To what extent are fed corps subject to prov regulation?

Depends on characterization of the prov legislation. If it’s just corporate character,

ineffectual, but if double character (legislation affecting property, civil rights) it is valid so

long as it doesn’t conflict w/federal legislation – must have conflict to trigger

paramouncy, not just overlap/duplication (Multiple Access Ltd. v. McCutcheon (1982)

[SCC])

o What about when prov legislation (when legitimately exercising prov power under s. 92(13) of CA)

“sterilizes” business activity of a fed corp?

John Deere Plow and Great West Saddlery (PC): business activities of fed corps have no

immunity from prov control/restrictions. However applied a test of whether prov. leg.

“impairs” or “sterilizes” essential capacities of federal corp.

Can. Indemnity Co. v. A.G. B.C. [1977](SCC): As long as provincial legislation is

constitutionally valid, “it may completely paralyze all activities” of a fed. corp.

Incorporation and its Consequences

BCBCA s.3, 10, 13, 17, 18, 30, 87

s.3

s.10

s.13(1)

s.17

s.18

s.30

s.87

A company is recognized under the Act when the incorporation, conversion, amalgamation, or

continuation occurs.

(1) One or more persons may form a company by (a) entering into an incorp agreement, or (b) filing an

incorporation application.

(2) Each incorporator must sign agreement + set out # of shares of each class for that incorporator.

A company is incorporated (a) at date + time application filed w/ registrar, or (b) at a later specified time.

Effect of incorporation – SH are capable of exercising the functions of an incorporated company with the

powers + with the liability on the part of the SHs provided in this Act.

Whether or not the requirements precedent + incidental to incorporation have been complied with, a

notation in the corporate register that a Co has been incorporated is conclusive evidence that the Co

has been duly incorporated.

A company has the capacity and the rights, powers and privileges of an individual of full capacity.

(1) No SH of a Co is personally liable for the debts/obligations/defaults/acts of Co.

14

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

3. The Corporate Entity

(a) Introduction

Prior to this case, there was a pervasive view that the legal consequences of incorporation were fairly limited…that

the same principles courts had applied to rights & liabilities of partners would still apply to shareholders of

corporations…

Salomon v. Salomon & Co.

[1897] A.C. 22 (H.L.)

Facts: Salomon was sole propietor (leather goods). Assets became the assets of the company (Salomon was then

known as a ‘promoter’). S got in return (i) cash (ii) shares {equity interest} and (iii) debenture over the company’s

assets {debt interest – defined in Act; also, an acknowledgement of debt, usually in writing. It can be registered at

the Business/Incorporation Registrar. It is granting a security for that debt over its assets. If the jurisdiction has the

capacity for that security to be registered, then you have a debenture}. When company was wound-up later, if the

amount realized from company assets was applied to debenture (to Salomon), the creditors would have been

screwed.

I/A:

Trial and Appeal held against Salomon: the company was Salomon’s agent and there was no separation b/w

Salomon and Salomon Ltd. However, on the facts there was no way to say that Salomon had abused the process

that allowed him to incorporate.

HofL said Salomon had not abused the statute; the statute invited him to do what he did. **If the HL had decided

this case differently, it would have seriously undermined the corporate form as we know it today.**

One of the allegations against S was that he had overvalued the business {over-rewarded himself for his business}.

However the court said it would not interfere – the business was good consideration; whether it was adequate is for

the market to decide. This approach to pricing is still good law – companies decide the price of the shares they are

offering and the market decides whether that is an adequate price. (Securities regulators do limit what companies

can get for their shares; add’ly the company may not be able to sell the shares.)

First instance of the Business judgment rule: legal principle that manifests the policy behind this approach: directors

are businesspeople, and courts, who are not businesspeople, should not second-guess directors’ decisions. This

avoids a huge amount of litigation over ‘bad decisions’.

Salomon brought in family members as directors. This was very common in Canada until the 1970s.

RATIO: (see p.85 – good description)

1. Corporation has separate legal existence apart from the personalities of its shareholders

2. There is no requirement that shareholders must hold their shares beneficially and no objection to de facto

one-person corporations.

Seminal case in establishing the corporate form as we know it today: corporation is a separate legal person.

NB: IMPORTANT - There may be situations where corporations may be agents of their shareholders, which lead to

“lifting the corporate veil.”

BCA ss.19, 17(2), 64, 121, 136

s.19 (Company Constitution) - Historical relic: tries to state incorporation and the relationship b/w the corporation

and its owners. In BC, known as “notice of articles” and “articles” OR “memorandum” and “bylaws.” See 19

September 2006 NB.

s.17(2) (BC Interpretation Act) If a company didn’t have directors, s.17(2) says: a majority of the members of a

corporation may bind the company – fallback provision that gives SH the ability to perform acts on behalf of the

15

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

company if there are no Ds. This is important because it indicates that the Ds are agents of the corporation. If Ds

are unable to act, a majority of the SH can act on the company’s behalf and bind it. See s.136 BCA

s.64

Directors have the power to issue shares (at time & price to be decided by them)

s.121

(Company Act) – the names of the first director(s) must be included on incorporation of the company. If a

company is WH (public) there must be at least 3 shareholders (s.120)

s.136

Widely-enough worded that it allows for Ds to be uninvolved in the day-to-day running of the business.

NB: ‘Promoter’ a person actively involved in the formation of a company. They have fiduciary-like duties; has been

problematic in BC.

NB: Priority on a winding up: Preferred creditors, secured creditors, unsecured creditors, shareholders.

Lee v. Lee’s Air Farming (1961 J.C.)

One spouse owned all but one share; he had appointed himself director for life; he was also the sole FT employee.

He was killed at work (plane into hillside). Wife tried to claim on his worker’s compensation but failed at trial and

subsequent appeals. Appealed to Privy Council who said that corporation is separate legal person and is capable of

contracting with someone through its agent. Also confirmed that you can be both a shareholder and an

employee.

What if this had been a partnership (b/w two spouses)? Paterson sees a partner as being able to be an employee of

his own partnership. (Check?)

Kosmopolous v. Const. Ins. Co. (1983) Ont CA (REEXAMINE)

Significant chunk of this is insurance law:

Insurable interest – in order to take out a K with an insurer, you must have an insurable interest in what

you’re seeking to insure. i.e. you can’t take out insurance on other people’s lives. However, this is mainly

relevant to real/personal property interests.

Subrogation – is what happens when an insurer pays an insured the proceeds of an insurance claim. i.e. ICBC

pays you for damage to your car (to have work done on car). Once pay out happens, ICBC can bring a claim in

your name against the other person. (Policy: this is to not bias juries by involving an insurance company in the

suit)

Facts: Classic sole proprietorship that decides to incorporate (under new CDN statutory regimes that allow sole

person-corporations). He transfers his business assets to the newly incorporated company but retains an insurance

policy that is in his own name in respect of the business’ premises. Insurance co says sorry, no insurable interest in

the building since it’s the company’s asset, not his.

Courts responded in two ways:

(a) No difference (esp. when sole shareholder) between you and corporation.

(b) No, you and corporation are separate legal persons; but a person who owns shares in corporation which

has insurable interest, that person should be regarded as having an insurable interest. (What threshold of

holding is required?)

Court gets into law of insurable interests. Says that if Kosmopoulus had taken debenture over property then he

would have had insurable interest and no problem.

However, since he was the sole shareholder…but ONCA uses benefit/detriment test and says Kosmopoulos does

have insurable interest b/c he is sole shareholder. Ziegel (critique) responds that this is wrong in law: (a)

undermines Salomon by modifying the corporate legal person, and (b) what about a company where there is

another shareholder that has a tiny other share? What’s the threshold? Canadian law has never articulated a

definite test of when the courts can modify the rule in Salomon’s case.

16

Corporations I

3/6/16

Audrey C. Lim

Ratio:

Case goes on to SCC which upholds on different grounds: MacIntyre SCJ wants to apply the ONCA reasoning and

rationale for one-person corporations. Majority supports Kosmo by reasoning on insurable interest: the idea that

you must have insurable interest to have insurance coverage is not determinative; instead they apply a moral

certainty / benefits/detriments test from Macina. So as an individual, had an insurable interest in the Co’s assets,

allowing him to take out an insurance policy so can now get benefits.

Important is “SCC not prepared to create any exceptions to the Salomon principle, even in the case of single-person

corporations.” This line of argument may be more susceptible to criticism, but we may not need to worry too much

about it (esp. as regards insurance law)

Categories of Companies in Canada

Two well known types: Widely held (aka. reporting companies; public companies) / closely held (aka. private

companies).

Two other variables exist:

One-person company – whether this is literal (Kosmopoulos) or in fact (i.e. Lee, Salomon). CDN courts don’t

treat them differently. The practical problem w/ 1-person corps is with meetings: CL rule that you cannot

meet with yourself (must be two or more people). Act therefore had to validate and define req’ts for oneperson meetings.

Holding/Subsidiary situation: many large (and some small) corporations own shares in other corporations

(and even in themselves). When is it appropriate to describe a corporation as being a subsidiary of its holding

company.

o {s.2(3)}: when the holding company has control of the subsidiary.

(i) de jure

Holding co owns more than 50% of shares in subsidiary, so can control

outcome of resolution at AGM; can guarantee who is elected to BoD or

(ii) de facto

Whether or not, in fact, the holding co can elect a majority of the BoD even

if you don’t have a clear majority. This is very important w/ WH companies

where it is unlikely to own 50%, but by owning 10-15% (ie) you may well be

able to get self or appointees elected and have de facto control}.

(b) Lifting the Corporate Veil

Lifting the Corporate Veil: Judge is willing, on facts of case, to modify the strict application of Salomon principle.

Importantly, in none of these cases are judges denying that there isn’t a separate legal person; instead they are

saying for the purpose of the issues before the court, we will modify some of the consequences of being a separate

legal entity. Also, despite attempts to categorize/theorize when courts may lift the corporate veil, there seems to be

none. Examples below show situations when courts may be flexible (but there are no hard and fast rules).

BCBCA, ss. 422 and 423: Dissolutions and cancellations of registration by registrar