Everyman vs. Doctor Faustus: A Morality Play Comparison

advertisement

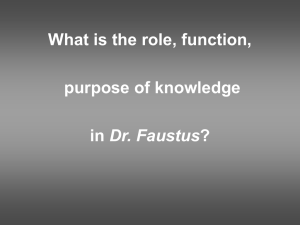

Everyman – Doctor Faustus Comparison Everyman, one of the most famous morality plays was born in 1475, but printed copies were only available from the 16th century. The morality plays were individual plays, performed by professional actors. They were performed on permanent stages, and they rather focused on plot and conflict than sight. Actually, the morality plays were dramatised sermons, visual representations of sins, virtues, etc. The Author of Doctor Faustus was Christopher Marlowe, who was a rival of Shakespeare. Marlowe preserved the morality features in his drama, but the beginning of renaissance had an effect on it as well. Neoplatonic magic and freethinking atheism are characteristics of Doctor Faustus, which was published in 1604. In both dramas, we can observe the same morality structure. They have the same central theme of human predicament, and man’s authentic existence. Both drama deals with transcendental topics, such as life and death, salvation and damnation. Man is responsible to a power higher than himself. The protagonists in the dramas (Faustus and Everyman) impersonates the average man, their name could be “anybody”. In both stories appears a messenger figure, in Doctor Faustus it is Mephistopheles, who tempts Faustus with the magic power in return of his soul. In Everyman comes Death, the “mighty messenger”, to tell Everyman that he should die. Then the protagonists start a journey, have to fight with the difficulties, but at the end they cannot escape their fate. “We are pilgrims on earth” – the medieval idea of life, which is the central topic of the moralities. However, in Doctor Faustus we can see the survival of morality structure, it has its renaissance features. In the medieval world God was in the centre, but in the renaissance the emphasis was on the individual, it was more human centric. Knowledge and learning became important, people wanted to know the world better. In Marlowe’s drama, Faustus is the representation of the renaissance man. He is reading, submerges in sciences. He denies God, and chooses to have magic power, to become a mighty god. “Magic” could be interchangeable with “science” in this case, suggesting Faustus’s craving for knowledge. Faustus gets the divine power indeed, but Evil cannot be defeated by only human intelligence. God’s help is needed as well. Faustus is said to be “a story of a renaissance man who had to pay the medieval price for being one.” At the end Faustus feels remorse, but he is dragged down to hell, which is the medieval approach to the result of sin. He becomes a tragic hero, who cannot cope with the circumstances, and met his downfall at last (as in renaissance tragedies). In contrast, in the Christian world there is no real tragedy. For example, Everyman’s end is elevating. Everyman dies, but Good deeds followed him to the grave, and he meets with God face to face with the most important “fellowpassenger”, and without his superfluous qualities. In both dramas appears the “dance macabre”, the last dance with death. This is a symbolic, picturesque approach to death, it appeared first in the middle ages, at the time of the black death. In both plays death reaches the characters, but while Everyman’s death means union with God, Faustus’s death is the perish of the soul. Source: my notes, and handouts on early English literature lectures in 2010 spring semester