New York Times Magazine

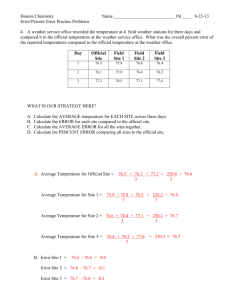

advertisement

New York Times Magazine August 14, 2005 The Other Army There are dozens of private security companies operating in Iraq, and Triple Canopy is one of the largest. How was it formed, who are its men ÷ and what is the line between 'security' and warfare? By Daniel Bergner When Matt Mann needed to buy armored vehicles, he phoned his brother-in-law, Ken Rooke. Rooke didn't know the first thing about bullet-resistant windows or grenade-resistant floors, but he wasn't 100 percent unqualified to do the buying. At least he knew something about cars. At a speedway in North Carolina, he once called races for a local radio station. He was the closest Mann could come to an expert. Mann, a retired U.S. Army Special Operations master sergeant in his late 40's, needed the vehicles quickly. And he needed guns. It was early last year, and the company he and two partners created, Triple Canopy, had just won government contracts to guard 13 Coalition Provisional Authority headquarters throughout Iraq. (The renewable six-month deals were worth, in all, about $90 million.) The C.P.A. was the governing body of the American-led military occupation. Triple Canopy -- not the American military -- would be protecting it. So would other companies. With the insurgency spiking, the job of keeping C.P.A. compounds from being overrun, and of keeping the architects of the occupation from being killed, had been privatized. Yet when Triple Canopy was hired, it scarcely existed. Mann and one of his partners, Tom Katis, an old friend from Special Forces, talked after 9/11 about starting a business that might somehow address the threat of terrorism. They thought they might use their military backgrounds to train government agencies in anti-terrorism techniques. On a Special Forces exercise in Central America (both men were, at that point, in the National Guard, Mann having moved on from the regular Army to work as a civil engineer and Katis having graduated from Yale and begun a career in banking), they dreamed of their unborn enterprise under the jungle foliage -- the layered jungle canopy from which they took their name. They didn't have much else. They were a name, a notion, when heard about the C.P.A. security work and started bidding for contracts. With money borrowed from family and friends, they hiring former Army colleagues on the chance that the company they the began might 1 somehow succeed. They had little but résumés to give them hope. The résumés, though, were impressive. Mann spent six years with the Army's Delta Force, its most selective, most keenly trained and most secretive unit, and he recruited retired Delta operators. He is an irrepressible man with full, close-cropped gray hair, blue eyes and a radiant smile, and as he told me about Triple Canopy's early days, he recalled his disbelief at the men who were drawn to the company. ''He wants to work for me?'' he said he thought, over and over. But his modesty went only so far. ''Rock stars like to work with rock stars,'' he said. The ex-Delta soldiers, heavily decorated and with all kinds of combat and clandestine experience, kept signing on. ''We were the squirrel trying to get a nut,'' Al Buford, an early employee and Delta veteran, remembered about the company's initial prospects for work. And when they were hired to protect well over half of the C.P.A.'s sites in Iraq, and to escort C.P.A. officials along the country's lethal roads, ''we had a whole truckload of nuts dumped down on us.'' So the call went out to Mann's brother-in-law, Ken Rooke. ''I'm a gearhead,'' Rooke told me. ''But we were shooting from the hip on this thing. I never felt competent in what I was doing.'' ''With the war going,'' he continued, there were no new armored vehicles to be had. He searched the Internet, made countless calls and bought a set of armored Mercedes sedans that once belonged to the sultan of Brunei before they were rented out to rappers. He replaced the stylish spoke wheels, and he put on run-flat tires, so the vehicles could be driven out of ambushes even after the tires had been blasted by gunfire. He learned how to ship his makeshift fleet to Iraq. For guns, too, Triple Canopy had to make do. Transporting firearms from the United States required legal documents that the company couldn't wait for; instead, in Iraq, it got Department of Defense permission to visit the dumping grounds of captured enemy munitions. The company took mounds of AK-47's and culled all that were operable. So Triple Canopy had vehicles and it had assault rifles, and when it needed cash in Iraq, to pay employees or buy equipment or build camps, it dispatched someone from Chicago, the company's home, with a rucksack filled with bricks of hundred-dollar bills. ''All the people in Iraq had to say is, 'We need a backpack,''' Mann said. ''Or, 'We need two backpacks.''' Each pack held half a million dollars. And in this way, one of the largest private security companies in Iraq was born. In this way, Triple Canopy went off to war. Plenty of 2 other companies have done the same, some that were more established before the American invasion, some less. The firms employ, in Iraq, a great number of armed men. No one knows the number exactly. In Baghdad in June, in a privately guarded coalition compound in the Green Zone, I talked with Lawrence Peter, a paid advocate for the industry and -- in what he called a ''private-public partnership'' - a consultant to the Department of Defense on outsourced security. He put the number of armed men around 25,000. (This figure is in addition to some 50,000 to 70,000 unarmed civilians working for American interests in Iraq, the largest percentage by way of Halliburton and its subsidiaries, doing everything from servicing warplanes to driving food trucks to washing dishes.) But the estimates, from industry representatives and the tiny sector of academics who study the issues of privatized war, are so vague that they serve only to confirm the chaos of Iraq and the fact that -despite an attempt at licensing the firms by the fledgling Iraqi Interior Ministry -- no one is really keeping track of all the businesses that provide squads of soldiers equipped with assault rifles and belt-fed light machine guns. Peter's best guess was that there are 60 companies in all. ''Maybe 80,'' he added quickly, mentioning that there were any number of miniature start-ups. He continued: ''Is it a hundred? Possibly.'' Triple Canopy now has about 1,000 men in Iraq, about 200 of them American and almost all the rest from Chile and Fiji. Its rivals include British firms that draw from the elite units of the U.K. military and outfits that draw from South African veterans of the wars to save apartheid. Australians and Ukrainians and Romanians and Iraqis are all making their livings in the business. Many have experience as soldiers; some have been in law enforcement. The firms guard the huge American corporations struggling to carry out Iraq's reconstruction. The private gunmen try to hold the insurgents at bay so that supplies can be delivered and power stations can be built. And companies like Triple Canopy shield American government compounds from attack. With guns poking out from sport utility vehicles, they usher American officials from meeting to meeting. They defend the buildings and people whom the insurgency would most like to reach. Throughout his time as head of the C.P.A., L. Paul Bremer III, whom the insurgency may well have viewed as its highest-value target, was protected by a Triple Canopy competitor, Blackwater USA. Private gunmen, according to Lawrence Peter, are now guarding four U.S. generals. Triple Canopy protects a large military base. And throughout Iraq, the defense of essential military sites like depots of captured munitions has been informally shared by private soldiers and U.S. troops. If the 25,000 figure is accurate, the businesses add about 16 percent to the coalition's total forces. 3 Yet it is hard to discern who authorized this particular outsourcing as military policy. No open policy debate took place; no executive order was publicly issued. And who is in charge of overseeing these armed men? One thing is sure: they are crucial to the war effort. In April 2004, within a few months of Triple Canopy's arrival in Iraq, its men were waging a desperate firefight to defend a C.P.A. headquarters in the city of Kut. The Mahdi Army had launched an onslaught. In the world of companies like Triple Canopy, a great deal of importance is attached to a very few words. The word ''mercenaries'' is despised. The phrase ''private military company'' is heatedly dismissed as inaccurate. ''Private security company'' (or P.S.C.) is the term of art. Semantics aside, private soldiers have been on the battlefield for thousands of years. As P.W. Singer, a scholar of privatized warfare at the Brookings Institution, recounts in his book ''Corporate Warriors,'' mercenaries served in the army of the King of Ur two millennia before Christ; the ancient Greeks supplemented their forces by contracting out for cavalry and for specialists in the slingshot; and private bands of Swiss pikemen, infantry with 18foot-long weapons, proved themselves superior to cavalry in the late 13th century and made themselves a necessary expense to the warring rulers of Europe for hundreds of years. But mercenaries began to fade from the battlefield around the Age of Enlightenment. Partly this was because of breakthroughs in the science of warfare. Better weapons demanded less skill from the fighter. The experience of the mercenary was needed less. With a decently designed musket, a fresh soldier could be trained fairly swiftly and dispatched to the front. And then, too, the 18th and 19th centuries brought new ideas about the sanctity of the nation and the honor of the citizen in soldiering for it. ''Those who fought for profit, rather than patriotism,'' Singer writes, ''were completely delegitimated.'' Still, the British hired 30,000 German Hessians to help them battle the revolutionaries in the American War of Independence. Yet gradually the work of the mercenary grew more and more marginalized and disdained, and in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 it was essentially outlawed, at least in wars between nations. Mercenaries carried on in the ignored and anarchic places of the world; through much of the second half of the 20th century, they played notorious roles in the insurrections of Africa. But then, in 1995, in the tiny West African country of Sierra Leone, private soldiering made a morality-twisting appearance. A rebel army was burning villagers alive and starting to develop its signature atrocity: hacking off the hands of civilians and letting them live 4 as reminders of rebel power. Desperate, the country's ruler hired a South African firm, Executive Outcomes, that was run by a former apartheid-era military commander. It presented itself as something other than a violent, shadowy employment agency for apartheid-era veterans. It had glossy brochures outlining its military services. Its leader called himself a chairman. Its work wasn't that of ''mercenaries'' or ''dogs of war''; it would soon adopt the term ''private military company.'' In Sierra Leone, using a few aircraft and about 200 men, Executive Outcomes rapidly drove the rebel army of perhaps 10,000 back to the country's hinterlands. Brutality erupted again as soon as Executive Outcomes left, but the world had seen that a small, well-trained private force could accomplish immeasurable good. Not long afterward, a London company led by a former British lieutenant colonel, Tim Spicer -- whose latest firm now has a nearly $300 million contract with the U.S. Department of Defense in Iraq -tried again to rescue the West African country. Spicer failed but emerged as a kind of spokesman for the moral value of private military companies. ''The word 'mercenary,' '' he told The Daily Telegraph of London in 1999, ''conjures up a picture in people's minds of a rather ruthless, unaligned individual, who may have criminal, psychotic tendencies. We are not like that at all. All we really do is help friendly, reasonable governments solve military problems.'' (No matter that Spicer had once considered providing his help to Mobutu Sese Seko, the tyrannical dictator of Zaire, for a price.) Britain's foreign secretary, Jack Straw, and a former United Nations under secretary general, Brian Urquhart, were soon talking about the possible use of private military companies to aid the U.N. in stabilizing the world's conflict zones. The U.N. wasn't remotely ready to hire private armies to end civil wars, but a subtle shift in perception had started to take place. In 2002, the U.S. government hired about 40 private gunmen, from the American company DynCorp, to keep President Hamid Karzai alive in Afghanistan. And in the spring of 2003, as Gen. Jay Garner, retired, established the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, the short-lived precursor to the C.P.A., as the occupation's governing body in Iraq, the Pentagon put a small contingent of South Africans and Nepalese Gurkhas from the British firm Global Risk Strategies in charge of protecting him and his staff. ''That,'' Garner told me when we spoke last month, ''was the genesis'' of the rise of private security companies in Iraq. The numbers, at the start of the occupation, were not large. Then, in the second half of 2003, as the C.P.A. expanded its presence across the country in its attempt to rule and rebuild, and as the insurgency mounted, the C.P.A. turned away from the coalition 5 forces, which had been providing a measure of protection, and looked to the companies for safety. Andrew Bearpark, the C.P.A.'s director of operations during that period, explained to me that he was closely and strongly advised by the U.S. military in Iraq -- and financed by the Department of Defense -- to make this move. Major contracts were put out for bidding. Triple Canopy was awarded its work in January 2004. Other companies received, or already had, their portions. (Meanwhile, the corporations actually doing the rebuilding, the hearts-and-minds element of the American occupation's campaign, were spending up to 25 percent of their U.S. government money on hired protection.) The deployment of private gunmen grew and grew into a profusion that may be explained partly by the subtle shift in perception that had removed some of the old mercenary stigma, and partly by the emphasis on outsourcing that had been gathering momentum in the U.S. military since the early 1990's (but that had been focused on logistical, unarmed support). Most immediately, though, the explosive growth may be explained by the strength of the insurgency in Iraq and by the apparent fact that there weren't enough troops on the ground to fight it. ''Sure, they are performing a military role,'' Garner said of the companies. Then, while noting that he wasn't criticizing the Department of Defense, he added, ''The gut problem is the force'' -that is, the U.S. fighting force -''is too small.'' And Bearpark, who has lately become a consultant to a large security firm, maintained that private protection might sometimes be better than what a regular army could offer. The private teams are more streamlined and flexible, he argued; they are often better trained for the job; and they may be willing to take more risks, allowing officials to move more freely. But about the fundamental reason for the C.P.A.'s hiring of the companies, he said: ''The military just hadn't provided enough numbers. It was stretched to the limit.'' The Department of Defense is reluctant to discuss the role of security companies in Iraq and precisely how it got so big. Over several weeks I called the Pentagon repeatedly, asking whether the secretary of defense or one of his under secretaries had, at any point, deliberated about the presence of some 25,000 armed men or perhaps authorized it in one way or another, piecemeal or in its entirety. These questions -- which no one I spoke to was able to answer -- elicited from departmental press officers a series of unfulfilled promises to help me get an answer. In the end, they sent an officially approved written statement, which detoured fully around the questions but included the key line, ''P.S.C.'s are not being used to perform inherently military functions.'' The Pentagon's reticence on the issue may be due to uneasiness over the now-common accusation that it didn't adequately plan for 6 battling an insurgency. (It may view questions about private gunmen as leading inevitably to questions about troop numbers.) But there is most likely an additional discomfort, a lingering problem with the companies' public image. For the shift in perception hasn't been complete; the hated word ''mercenaries'' still hovers near. With this problem, the firms are doing their best to help. Many of them have tried to rechristen themselves again, to further separate themselves from the past, from the old infamy of ruthless, insurrection-stirring white freelancers in Africa, to make their work palatable to all. When I met with Lawrence Peter, a short man with a fiery voice, he raged that the press refused to accept the companies' newly chosen term: ''We are not private military companies! We are private security companies! Private security!'' He justified the distinction by saying: ''The work is defensive. We protect.'' Sometimes, though, the distinction seems secondary. No matter what you want to call Triple Canopy and its men, when the Mahdi Army -- a radical Shiite force loyal to the militant cleric Moktada al-Sadr -- attacked at Kut, the primary truth was that the company was fighting a war. A current training adviser for Triple Canopy was, in early April 2004, in charge of defending the occupation's Kut headquarters. (For security reasons, it is Triple Canopy policy that employees now in Iraq or likely to return not be identified by their full names.) John, a tall spike of a man of 50, with a graying brush mustache, spent 26 years in the U.S. Army, much of that time with Delta. He was on the first invading helicopter into Grenada in 1983; his helicopter and the others behind him were riddled and ravaged by bullets, and three soldiers sitting near him were shot. ''I've never taken so much fire again till Kut,'' he told me in May. ''Kut was like stepping out into the air -- you know you might not exist any longer.'' Facing a river and enwrapped on three sides by the small, mostly Shiite city, the C.P.A. compound in Kut consisted of several oneand two-story concrete structures. The buildings had been Baathist offices and a hotel. There the coalition's regional ruler, known as the governorate coordinator, worked and lived with a crew of reconstruction officials and contractors, surrounded by 12-foot-high blast walls at the compound's perimeter -- except along the river, where, John told me, the governorate coordinator, a Brit, preferred that nothing obstruct the view. The city had been fairly peaceful. It was a ''sleepy hollow,'' John recalled his Triple Canopy boss telling him, joking that it was a suitable post for an old, graying man to guard. The first sign of siege was the massing of more than a thousand demonstrators in a few clusters around the city and around the 7 compound, demanding that the C.P.A. leave Kut. Many in the crowds carried assault rifles and grenade launchers. John sensed, he said, that the protest at the compound might be a ruse, a cover for casing the site. Word came that the coalition-trained Iraqi police had abandoned their stations and checkpoints throughout the town, that the Mahdi fighters had claimed their weapons and uniforms. John had a core team of three Triple Canopy gunmen. There were about 40 Ukrainian coalition troops posted at the compound. The Iraqi guards employed by Triple Canopy were already starting to quit and to flee. John declared ''lockdown'' and waited for whatever would come. Civilians strapped on their flak jackets and bulletproof vests. They prepared to retreat to a central spot within the hotel, a last point of defense, if the compound's perimeter was overrun. Warnings filtered in of car bombs set to strike. Through the night, two cars seemed to be casing the gates. Morning brought the sound of gunshots around the town -- and the ominous realization that the area just outside the compound was now desolate. Gunfire and rocket-propelled grenades started to hit around noon. The assault came from nearby, as close as the buildings across the street. It came from all sides. Mortars crashed in. A grenade exploded into a C.P.A. Suburban; the vehicle was consumed in flames. ''1740: Mortar fire has increased from across the river,'' reads a minute-by-minute account kept by a civilian contractor. Windows shattered; large fragments cracked from building walls; vehicles were ripped apart. The enemy barrage of artillery and small arms surged and slackened and surged again. ''Throughout the battle, the commander of compound perimeter defense by de facto is John,'' states another contractor's hour-by-hour report. John climbed to the hotel roof to direct return fire. The three Triple Canopy gunmen manned the towers. Successive shifts of Iraqi guards had by now flooded out the gates after one was slightly wounded and a translator spread the rumor that the Americans planned to abandon them all to their deaths. Just two local soldiers remained; John put them on a machine gun. For hours the Ukrainians battled relentlessly; when they ran low on ammunition, John resupplied them with Triple Canopy rounds, the minute-by-minute account relates. He sent a fourth Triple Canopy soldier, a young dog handler who'd never seen a moment of combat, to race from tower to tower, taking bullets and water to the other T.C. fighters, who, John said, ''slung lead like you wouldn't believe,'' 2,500 rounds, he guessed. Triple Canopy's bomb-sniffing dog was left tied in the hotel and howled every time a mortar exploded. On the roof and rushing through the compound between blasts, John juggled three radios and a satellite phone between his hands and combat vest pockets. None of the contingents he needed to speak with -- Triple Canopy; the separate company that handled the governorate coordinator's personal security (and that had pulled back to protect 8 him within the compound); the civilian contractors; the U.S. military liaison in another town -- used the same communication system. He implored the military to send attack aircraft to scatter al-Sadr's men, who probably numbered 200 to 400. The battle flared through the night. Heavy machine guns opened up from across the river. ''2200: There is an air-lift evacuation plan being put together.'' Two hours later: ''We were advised by T.C. that the air evacuation was scrubbed'' -- the odds of a helicopter being shot down while landing or lifting off were too high. An American plane at last arrived, its canons spewing shells. The militia went quiet, but then: ''0100: The hotel is hit several times and the building shakes from the impact. This fire seems to be the worst yet of the engagement.'' There appeared to be no escape; John figured the defense might be finished; on his radios and satellite phone he tried to keep his voice controlled, to keep his words, as he recounted, ''on the level of an information exchange.'' U.S. helicopter gunships then flew overhead. They held fire, but the enemy took cover again. And near dawn, in the lull, John and the Ukrainians carried out an order from the main C.P.A. headquarters in Baghdad that everyone should drive out of the compound, no matter what the risk in exposing themselves. They went in a mix of armored cars and open-sided trucks. ''Every turn you made, you didn't know,'' John said. He waited for mortars and R.P.G.'s to annihilate them. But the gunships tracked their route. No enemy fire came; they reached the closest coalition base; the civilians and soldiers of the compound had survived the battle without a serious wound. The same week, a hundred miles to the west in the town of Najaf, eight private soldiers from the Blackwater company fought al-Sadr's Mahdi Army, stopping them from overrunning the C.P.A. headquarters there. The Blackwater men went unscathed. But just across town from John during the Kut fighting, the Mahdi Army attacked a building that housed five gunmen from the Hart Group, a British firm protecting the reconstruction of Iraq's electrical grid. The five were wounded, and one, pinned down on the building's roof in a firefight, bled to death. A week earlier, four Blackwater soldiers, escorting a kitchen-supply truck to a U.S. military base, were ambushed and shot by insurgents in Fallujah -- their bodies roped to the back of a car and dragged through the streets, set on fire, torn apart and put on display, dangling from a Fallujah bridge. At the time, the Fallujah killings seemed notable not only for their brutality but also for the fact that private security men had been the victims. Yet private security men in Iraq are embattled constantly. Between 9 January and August 2004 (the last period for which the company has compiled figures), Triple Canopy teams came under attack 40 times, in incidents ranging from incoming rounds of rocket-propelled grenades to assaults lasting at least 24 hours. And the count of 40, I was told by the company's director of operations, represented only attacks in which Triple Canopy fired back. Six to eight times that number of assaults -- from sprays of enemy bullets to mortar fire -had gone unrecorded, a company spokesman estimated. The frequency of attacks remains about the same now. The style has shifted away from assaults like the one at Kut, but guerrilla ambushes are on the rise. It is impossible to say exactly how many private security men have been killed in Iraq. Deaths go unreported. But the figure, according to Lawrence Peter, is probably between 160 and 200. That's more deaths than any one of America's coalition partners have suffered. "Some people will tell you they're here for Mom and apple pie,'' a private security man with another company told me. (He didn't want his or his company's name printed, he said, because neither his colleagues nor the industry in general think kindly of conversations with the media.) ''That's bull. It's the money.'' We sat between low concrete buildings at Triple Canopy's Baghdad base. The roofs are four feet thick and specially layered to absorb major blasts. The base sits within the Green Zone, behind high walls that divide the coalition's vast self-delineated borough from the severe danger of the rest of Baghdad. But the zone, as the people living and working there like to say, is these days less green than almost red: mortars rain in. The man's company put him up at Triple Canopy's freshly built complex, with its pristine dining hall and ramshackle gym, its guard towers and long shipping container full of ammunition. The base is large enough that other outfits can rent rooms. Triple Canopy has come a long way from its haphazard beginnings. Its current contracts in Iraq, mostly with the U.S. Department of Defense and the State Department, are worth almost $250 million yearly. And having succeeded in Iraq -- Triple Canopy hasn't had a single worker or client killed -- it has just been named one of three companies that will divide up $1 billion annually in newly created protection work with the State Department in high-risk countries around the world. But the private security man I sat with wasn't talking about windfalls on that level. He was talking about his own income. ''I'm richer than I've ever been,'' he said. ''I'm not in debt to nobody.'' He had jowls and loose swells of flesh beneath his T-shirt. ''Don't 10 let the package fool you,'' the ex-Delta colonel who introduced us had told me. ''He's a commando from way back.'' After a career in Special Forces, the man said, he hadn't seemed able to survive in the civilian world. Work in construction fell apart. He drank heavily. He took a job as a cashier in a convenience store -- ''till I found out I had to smile at the customers.'' He laughed ruefully at his inability to adapt. But now, when his 16-year-old son sent him an e-mail message from back home in South Carolina, with a picture to prove that he'd mowed the lawn the way his mother had asked, he could buy the boy some tech equipment as a gift. ''I'll stay until this is over,'' he said. ''The money's too good.'' He didn't specify his salary, but Americans and other Westerners in the business tend to make between $400 and $700 a day, sometimes a good deal more. (The non-Westerners earn far less. Triple Canopy's Fijians and Chileans make between $40 and $150 dollars each week and sleep in crowded barracks at the Baghdad base, while the Americans sleep in their own dorm rooms. The company explained the difference in salaries in terms of the Americans' far superior military backgrounds and their higher-risk assignments.) Americans with Triple Canopy stay in Iraq for three-month rotations, working straight through. Then they're sent on leave for a month, returning if they wish. Depending on how much time they spend in the States over the course of a year, most of their income can be tax-free. Yet it wasn't all about the pay, not for everyone. ''The money, sure,'' Al, a Triple Canopy manager in Baghdad, said. Like plenty of others with the company, he was middle-aged and had retired from the rarefied world of Delta. ''But it's the excitement, the camaraderie.'' And back in the Chicago suburb where I visited the company in May, in its new, sprawling offices (which Triple Canopy would soon be exchanging for a similar setup outside Washington, in order to be closer to its main source of income, the U.S. government), I heard Matt Mann talk exuberantly about ''creating a national asset.'' It would have been easy to be exuberant merely because of the profits he was taking in; it would have been easy to be downright giddy. But his enthusiasm seemed to come, as well, from other things. He spoke about the waste of Special Operations stars, ''men whose intelligence is equal to the best attorneys, the best doctors,'' men who had survived the harshest training, who had learned to operate on their own in alien cultures, who ''don't know how to fail.'' Their talents, he said, were going unrecognized and unused when they left the military and entered civilian society. A long window beside him looked out on a perfectly manicured office park, its pond rippling delicately. Wearing jeans and a short-sleeved sport shirt with a summery print, he leaned back behind his blond wood desk, 11 hands behind his head, strong, tanned arms on display. In a sense, he might have been any renegade businessman who had conjured a new product and found himself in a spot of corporate comfort. But a map of Iraq, its yellow tones in quiet contrast to the blond of the wood, was posted on the wall. He didn't care to talk about his personal thoughts on the war but saw himself as creating a collection of talent that was driven less by the '' 'me' mind frame,'' he said, than by patriotism. In an office near Mann's sat Al Buford, the company's manager of recruiting, wearing sharply pressed khakis and a pale blue dress shirt. On a bookshelf behind him, a framed photograph showed him in jungle camouflage, on an Army Special Operations mission in Panama. Facing him on his desk, his computer was loaded with scores from the psychometric exam Triple Canopy gives its potential employees. The company's three-week training and selection course includes multiple-choice word analogy and number pattern questions between the high-speed driving drills and target tests at the firing range. And there are hundreds of questions designed to catch personality problems before the company gives a candidate a gun and sends him off to Iraq. Other firms take a different approach. One morning, at a military base near the Baghdad airport, a Triple Canopy soldier I was with ran into a friend who had just been fired by the company. The friend had been drunk repeatedly; he'd been caught drinking right up to the hour he was slated for armed escort of a client. The previous day, the friend told us, he went to talk with another American company. Today he was signing a contract. There is no effective regulation in Iraq of whom the firms hire or how the men are trained or how they conduct themselves. ''At best you've got professionals doing their best in a chaotic and aggressive environment,'' Lyle Hendrick said in an e-mail from Iraq in July, describing his colleagues in private security there. He had spent six months with one company in the country's north and is now with another down in Basra. ''At worst you've got cowboys running almost unchecked, shooting at will and just plain O.T.F. (Out There Flappin').'' I had come to know Hendrick, a tall, soft-spoken, part Blackfoot Native American from South Carolina, while he was on leave in the States. He had been a Special Forces captain, then a private detective; he eventually ran out of money as he let work slip to care for his stepfather, who had had a severe stroke. When he signed on with his first company and, in June of last year, flew into Mosul, a hotbed of the insurgency, a convoy of pickup trucks arrived at the airport to meet the new hires. To his uninitiated eyes, the men in the vehicles ''looked like extras in Mel Gibson's Road 12 Warriors,'' he said. They told him to climb in and to stay ready to shoot while they drove, to watch his sector. ''There was no instruction, no sit-down, no here's how we operate; it was, throw your stuff on the truck and let's go.'' A few months later, he was riding in a convoy, in the back seat of a pickup's cab, escorting an Army Corps of Engineers team to a spot out in the desert, where they would blow up captured munitions. Across the desolate terrain, according to Hendrick and a colleague who was present that day, a white S.U.V. appeared from behind a berm. It was on Hendrick's side, 200 yards away. Hendrick wore a black helmet, tinted goggles and a black shirt, with a kaffiyeh wrapped around his neck and taupe-colored shooting gloves. He leaned out his window clutching a belt-fed light machine gun. The distance kept closing. ''He's coming in! He's coming at us!'' he heard someone on his team call out. He thought, Idiot farmer. He had the best angle; he fired warning shots. He could see the driver dressed all in white. The distance shrank to less than 30 yards. He aimed into the wheels. ''Idiot farmer turned to No, this isn't happening in a fraction of a second,'' he said. All was instinct. He riddled the driver's door and shot into the driver's window. The S.U.V. jerked to the side -- it exploded, ''went from white to a ball of bright orange,'' so close that the blast demolished a vehicle in the convoy, though the men inside weren't hurt. The S.U.V. all but vaporized. It had been packed with explosives -- a suicide bomber. The largest trace left was a scrap of tire. A bit of the bomber's scalp clung to one of the vehicles in the convoy. Hendrick showed me photographs of the smoky aftermath. He wanted to be sure I understood the kind of circumstances he and his colleagues were dealing with. But he also said, ''This whole thing has brought out some pretty scary characters.'' He mentioned a newspaper article about one of the men he'd worked alongside. The man was arrested when he went on leave back to the States. Apparently the security company hadn't done much of a background check, if it had done one at all; it turned out the man was a fugitive in Massachusetts. He had been charged with embezzlement. He had also violated the terms of a suspended sentence in a separate case, a local paper in Lowell, Mass., explained: he'd been convicted of assault ''for nearly blowing a friend's jaw off during a game of Russian Roulette.'' Mark raised his strong forearms and performed a pantomime of washing his hands and flicking off the water. A manager with Triple Canopy in Baghdad, Mark was sitting behind his desk at T.C.'s base, demonstrating the Department of Defense's attitude about overseeing and policing the private security companies. ''D.O.D. doesn't want anything to do with it,'' he said. ''They don't have time. They don't have the numbers. And State can't investigate incidents. They don't have the investigators. So there's Iraqi law. Not that Iraqi 13 law really exists. Am I going to give up my weapons to Iraqi police? I don't think so. That could get me killed.'' No one knows how many times gunfire from a private security team has wounded a bystander or killed an innocent driver who ventured too close to a convoy, not realizing that mere proximity would be taken for a threat. When they fire their weapons in defense or warning, the teams rarely concern themselves with checking for casualties -it would be too dangerous; they are in the middle of a war. Besides, no one in power is watching too closely. And what rules exist seem to be ignored. A C.P.A. decree, which has now evolved into Iraqi law, limits the caliber and type of weapons that private security personnel employ. But I was told by several people in the business that, especially outside Baghdad, weapons like heavy machine guns and grenades are -- perhaps by necessity -sometimes part of the arsenal. A few of the major American and British firms, Triple Canopy among them, advocate careful supervision of their business by their governments and possibly, in the future, by the United Nations. They'd like checks on everything from adequate training to human rights violations. They'd like to see their more rash competitors lose their contracts. They'd like to legitimize the work, to remove the remaining stigma that their own men are rogues, mercenaries. Back in October of last year, a Congressional bill demanded that the Department of Defense come up with a plan to manage the security companies -- to investigate individual backgrounds and inculcate rules of engagement and enforce compliance. Until then, according to a Pentagon official with knowledge of the process who asked not to be named because the Pentagon plan is still being finalized, the department had been at work, for many months, on doctrine dealing in a general way with all types of private contractors in Iraq but not specifically addressing the huge sector of gunmen. It seems that only the October bill drove the Pentagon to formally account for the most vital, and potentially most troubling, part of its outsourcing. Congress gave the department six months to produce its plan. Nine months have passed. The Pentagon has now promised the document any day; there's no telling whether it will change anything -- what guidelines it will give, what level of commitment will be behind them. When I asked the Pentagon official about who would enforce the rules in Iraq, I was told that the country's new sovereignty would be ''the context.'' It was hard not to think that the infant government of Iraq would be left mostly on its own to control the thousands of private gunmen that the American-led occupation has introduced to the country. It was hard not to think that the companies would be left to govern themselves. 14 Fourteen armed security men, traveling in a convoy through Fallujah in May, were detained by U.S. Marines, the first and only time, it appears, that the military has made such a detention. A Marine memo, quoted in The Washington Post, accused the men, who worked for a company called Zapata Engineering, of ''repeatedly firing weapons at civilians and marines, erratic driving and possession of illegal weapons'' -- six anti-tank weapons, the Zapata men later explained, kept for defense and condoned, they claimed, by the U.S. military. The security men (eight of them former marines) said they had fired only typical warning shots at civilians. They insisted that their bullets had never struck close to any servicemen. They suggested that their detention -- which lasted three days before they were released, without charges so far -- was driven by jealousy over their pay. They told of being roughed up and taunted, of being asked, ''How does it feel to be a rich contractor now?'' This kind of resentment may be deepening. What Matt Mann called a ''national asset'' may be corrosive. And the private security companies are, almost surely, eroding elite sectors of the military; the best-qualified troops, the men most desirable to the companies, are lured by private salaries that can be well more than twice their own. The Special Forces have lately responded with re-enlistment bonuses of up to $150,000. It's not enough. One Triple Canopy man in his mid-30's, with about 15 years of Special Operations experience, told me that his commander had begged him to stay in the service. ''But there was no way,'' he said. ''Here I get to be with the best and make so much more money.'' Triple Canopy, Mann had said to me, has a policy of never recruiting directly from the military. But when this man quit the Army, he knew exactly where he wanted to go. And plenty of his old friends from ''the unit'' -- a Delta soldier's oblique way of referring to his exclusive caste -- were poised to follow. There may be a danger that something else could erode eventually, if there is a drift toward using more private gunmen -- in yet more military ways -- to compensate for the inevitable reduction of troops in Iraq or to wage other wars. There may be the loss of a particular understanding, a sense of ourselves as a society, that we hold almost sacred. Soldiering for profit was taken for granted for thousands of years, but the United States has thrived in an age when soldiering for the state -- serving your country -- has taken on an exalted status. We often question the reasons for making war, but we tend to revere the soldiers who are sent off to fight. We honor their sacrifice, we raise it up and in it we see the value of our society reflected back to us. In it we feel our special worth. We may not know what to think of ourselves if service and sacrifice are increasingly mixed with the wish for profit. We may know less and less how to feel about a state that is no longer defended by men and women we can perceive as pure. 15 But that is an abstract and perhaps a distant worry. To wonder what will happen when the private work in Iraq finally winds down is a more concrete concern. What will happen to these companies, these men, without these thousands of jobs? Some will get contracts protecting U.S. departments and agencies around the world. Some will do the same for other governments. Doug Brooks, whose Washington industry organization, the International Peace Operations Association, represents several of the largest firms, says he believes the United Nations will soon hire the companies to guard refugee camps in war zones. But some of the firms and some of the men will no doubt be offered work by dictators or terrible insurgencies -- or by the kind of oil speculators who reportedly backed a recent mercenary-led coup plot in Equatorial Guinea (a plot involving former members of Executive Outcomes), in an attempt to install a ruler to facilitate their enterprise. And with so many newly created private soldiers unemployed when the market of Iraq finally crashes, aren't some of them likely to accept such jobs -the work of mercenaries in the chaotic territories of the earth? At their Baghdad base, eight Triple Canopy gunmen and I got into an S.U.V. and a sedan, the armored doors heavy enough that opening them felt like pulling them against water. The men, in T-shirts and bulletproof vests stuffed with ammunition clips, were ready to make the morning's run. I was the person they would be escorting. They figured that would be a decent way to give me a sense of how they work. I had to get to the airport, anyway. At a pre-run meeting, their team leader told them that the loud blasts we all heard a few hours earlier had been a series of V.B.I.E.D.'s -- vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices -- in a neighborhood adjacent to the Green Zone. He told them that optimal speed for the run would be 100 miles per hour. They didn't need to be told that the five-mile strip of highway between the Green Zone and the airport is known as the most dangerous road in the world. The insurgents plant remote-controlled bombs on the shoulders or sit on the access roads in cars packed with explosives, and they wait. They look for sets of vehicles that appear to belong to security teams -- teams that are their enemy and that shield enemy officials. The armor on the S.U.V. and the sedan wasn't going to do enough against bombs; it might not do enough against rocket-propelled grenades. Each vehicle held a rucksack full of ammunition in case an attack crippled the cars and left the men in a long firefight. A medic goes on every run. Sitting on my left in the back seat of the S.U.V., twisted to the side to peer through his window with rifle in hand, the medic pointed out to me an extra transfusion kit. ''You'll need to try and use that if I'm bleeding to death,'' he said. 16 We didn't get far from the Green Zone gate. Traffic was thick on the highway, and slow speeds allow the insurgents to better strike their targets, timing the detonations of their roadside bombs or driving close with their suicide cars. A white fuel truck appeared alongside us, its tank ready to erupt with the launching of a grenade. We veered onto the dirt median and fled back to base. ''We're a boring company,'' Al, one of the managers, had told me. ''We mitigate risk.'' An hour later the team leader decided to give it one more try. We sped away from the Green Zone, accelerating hard onto the highway. ''White van tracking us!'' a gunman called. On the access road, the suspicious van kept pace. Then, suddenly, we were braking. Traffic crawled and doors were ''cracked.'' That is the company term: doors are opened as little as possible, and rifles are pointed out -- the response when other vehicles get too near. The windows on armored vehicles are so heavy that they don't reliably roll up once they're rolled down, so Triple Canopy's men don't use the windows to point their guns. The doorcracking is rehearsed procedure; they can ride this way at top speed, leaning out to aim their guns in warning, or to put bullets into the engine of an oncoming car. They did it now at almost no speed at all. Traffic was barely creeping. ''Watch this guy on the right!'' To the right and behind, the threat edged closer. I couldn't help thinking of Lyle Hendrick, of the suicide bomber he'd shot at the last instant. But now, instead of firing, the gunman to my right lifted a hand off his barrel and raised bunched fingers in the air, an Iraqi signal, telling the driver to stop, to back off. Whether by luck or instinct, it was a good call. The driver quit inching forward, his attention caught by the fingers or the muzzle. We steered onto the shoulder, passing a dozen cars to reach the head of the stalled traffic. ''Big Army'' was there -- the companies' name for the regular forces. The troops waved us down. They told us they'd found a bomb on the road a few hundred yards ahead, and we waited for their explosives crew to set it off. A concussive wave surged through our chests; smoke billowed over the pavement. Then the way to the airport was clear. The military gate grew visible. Just outside it, another company's convoy was ambushed earlier in the week. But already, around me in the S.U.V., the men relaxed slightly as we approached the checkpoint. And once we were through it, muscles -- around eyes, across backs -- slackened perceptibly. For the moment, risk seemed all behind us. 17 Daniel Bergner, a contributing writer, is the author of ''In the Land of Magic Soldiers: A Story of White and Black in West Africa.'' 18