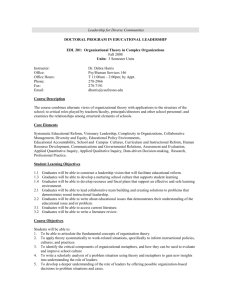

Management Skills Development

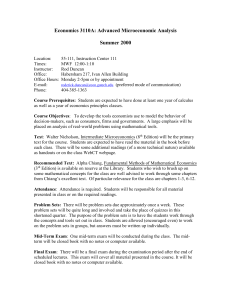

advertisement