What is Java?

advertisement

In this tutorial series, you’ll become familiar with Java, the programming language

used to develop Android applications. Our goal is to prepare those already familiar

with one programming language, such as PHP or Objective-C, to become

comfortable working with the Java programming language and dive into Android

app development. In this tutorial, you’ll get a brief introduction to Java

fundamentals, including object oriented programming, inheritance and more. If

you’re new to Java, or just looking to brush up on the details, then this is the tutorial

series for you!

Getting Started

As far as prerequisites go, we’re going to assume you understand how to program

(perhaps in PHP, or Visual Basic or C++), but that you are unfamiliar with the

specifics of programming in the Java language. We aren’t going to teach you to

program; we’re going to provide you with clear examples of commonly used Java

language constructs and principles, while pointing out some Android-specific tips

and tricks.

What You’ll Need

Technically, you don’t need any tools to complete this tutorial but you will certainly

need them to develop Android applications.

To develop Android applications (or any Java applications, for that matter), you need

a development environment to write and build applications. Eclipse is a very popular

development environment (IDE) for Java and the preferred IDE for Android

development. It’s freely available for Windows, Mac, and Linux operating systems.

For complete instructions on how to install Eclipse (including which versions are

supported) and the Android SDK, see the Android developer website.

What is Java?

Android applications are developed using the Java language. As of now, that’s really

your only option for native applications. Java is a very popular programming

language developed by Sun Microsystems (now owned by Oracle). Developed long

after C and C++, Java incorporates many of the powerful features of those powerful

languages while addressing some of their drawbacks. Still, programming languages

are only as powerful as their libraries. These libraries exist to help developers build

applications.

Some of the Java’s important core features are:

It’s easy to learn and understand

It’s designed to be platform-independent and secure, using

virtual machines

It’s object-oriented

1

Android relies heavily on these Java fundamentals. The Android SDK includes many

standard Java libraries (data structure libraries, math libraries, graphics libraries,

networking libraries and everything else you could want) as well as special Android

libraries that will help you develop awesome Android applications.

Why is Java Easy to Learn?

Java is easy to learn for a variety of reasons. There’s certainly no shortage of Java

resources out there to help you learn the language, including websites, tutorials,

books, and classes. Java is one of the most widely discussed, taught, and used

programming languages on the planet. It’s used for many different types of

programming projects, no matter their scale, from web applications to desktop

applications to mobile applications.

If you’re coming from a traditional programming background like C or C++, you’ll

find Java syntax quite similar. If you’re not, then take comfort in knowing that

you’ve chosen one of the easiest languages to learn. You’ll be up and running in no

time at all.

Finally, Java is one of the most human-readable languages out there, by which we

mean that a person who knows nothing about programming can often look at some

Java code and have at least an inkling what it’s doing. Consider the following

example:

1.

char character = 'a';

2.

if(character=='a')

3.

{

4.

5.

doSomething();

} else {

6.

7.

doSomethingElse();

}

If you simply read the code aloud, you can pretty much tell that this snippet of code

is doing. There’s a single letter variable called character. If the character variable

equals the letter a, then we do something (call the doSomething() method), otherwise

we do something else (by calling the doSomethingElse() method).

Why is Platform Independence Important?

With many programming languages, you need to use a compiler to reduce your code

down into machine language that the device can understand. While this is well and

good, different devices use different machine languages. This means that you might

need to compile your applications for each different device or machine language—in

other words, your code isn’t very portable. This is not the case with Java. The Java

compilers convert your code from human readable Java source files to something

2

called “bytecode” in the Java world. These are interpreted by a Java Virtual

Machine, which operates much like a physical CPU might operate on machine code,

to actually execute the compiled code. Although it might seem like this is inefficient,

much effort has been put into making this process very fast and efficient. These

efforts have paid off in that Java performance in generally second only to C/C++ in

common language performance comparisons.

Android applications run in a special virtual machine called the Dalvik VM. While

the details of this VM are unimportant to the average developer, it can be helpful to

think of the Dalvik VM as a bubble in which your Android application runs,

allowing you to not have to worry about whether the device is a Motorola Droid, an

HTC Evo, or the latest toaster running Android. You don’t care so long as the device

is Dalvik VM friendly—and that’s the device manufacturer’s job to implement, not

yours.

Why is Java Secure?

Let’s take this bubble idea a bit further. Because Java applications run within the

bubble that is a virtual machine, they are isolated from the underlying device

hardware. Therefore, a virtual machine can encapsulate, contain, and manage code

execution in a safe manner compared to languages that operate in machine code

directly. The Android platform takes things a step further. Each Android application

runs on the (Linux-based) operating system using a different user account and in its

own instance of the Dalvik VM. Android applications are closely monitored by the

operating system and shut down if they don’t play nice (e.g. use too much processing

power, become unresponsive, waste resources, etc.). Therefore, it’s important to

develop applications that are stable and responsive. Applications can communicate

with one another using well-defined protocols.

Compiling Your Code

Like many languages, Java is still a compiled language even though it doesn’t

compile all the way down to machine code. This means you, the developer, need to

compile your Android projects and package them up to deploy onto devices. The

Eclipse development environment (used with the Android Development plug-in)

makes this pretty painless. In Eclipse, automatic compilation is often turned on by

default. This means that every time you save a project file, Eclipse recompiles the

changes for your application package. You immediately see compile errors. Eclipse

also interprets Java as you type, providing handy code coloring and formatting as

well as showing many types of errors as you go. Often, you can click on the error

and have Eclipse automatically fix a typo, or add an import statement, or provide a

method stub for you, saving lots of typing.

You can still manually compile your code if you so desire. Within Eclipse, you’ll

find the Build settings under the project menu. If you have “Build Automatically”

turned on, you can still choose the “Clean…” option that will allow you to do full

rebuild of all files. If “Build Automatically” is turned off, “Build All” and “Build

3

Project” menu options are enabled. “Build All” means to build all of the projects in

the workspace. You can have many projects in an Eclipse workspace.

The build process, for regular Java projects, results in a file with the extension of

JAR – Java ARchive. Android applications take JAR files and package them for

deployment on devices as Android PacKage files with an extension .apk. These

formats not only include your compiled Java code, but also any other resources, such

as strings, images, or sound files, that your application requires to run as well as the

Application Manifest file, AndroidManifest.xml. The Android Manifest file is a file

required by all Android applications, which you use to define configuration details

about your app.

What is an Object Oriented Programming Language?

Okay. Time for a very brief and 20,000 foot view of object oriented programming

(OOP). OOP is a programming style or technique that relies upon the definition of

data structures called objects. For those new to OOP, an object can be thought of

much like a custom data type. For example, you might have a Dog object, which

represents the blueprint for a generic dog, with a name, breed, and gender. You could

then create different instances of the Dog object to represent specific dogs. Each Dog

object must be created by calling its constructor (a method that has the same name as

the object itself, and may or may not have parameters for setting initial values). For

example, the following Dog objects use a constructor with three parameters (name,

breed, gender):

1.

Dog dog1 = new Dog("Lassie", collie, female);

2.

Dog dog2 = new Dog("Fifi", poodle, female);

3.

Dog dog3 = new Dog("Asta", foxterrier, male);

So where is this Dog object defined? Well, here we need to begin defining some of

the fundamental building blocks of the Java programming language. A class

provides a definition for an object. Therefore, there is a Dog class somewhere—

either defined by you or in some library somewhere. Generally speaking, a class will

be defined in its own file, with the filename matching the class name (e.g. Dog.java).

There are exceptions to this rule, such as classes defined within other classes (when a

class is declared within a class, it is generally defined for use within the parent class

only as a helper class, and referred to as an inner class).

When you want to reference an object from within another class, you need to include

an import statement in the top of your class file, much like you would use a #include

statement in a compiled language like C.

A class typically describes the data and behavior of an object. The behavior is

defined using class methods. Method is the common term for a subroutine in an OOP

language. Many common object classes are defined in shared class libraries like

software development kits (SDKs), whereas others are defined by you, the

4

developer, for your own purposes. Software is then built up by using and

manipulating object instances in different ways.

Please realize this is a very generalized definition of OOP. There are entire books

written on this subject. If you’d like to know more about OOP, here are a few

resources you might want to check out:

Wikipedia has a nice overview of OOP

Sun Java Tutorials on Java

The Java Tutorials at Oracle

Note: We use a lot of different terminology in this tutorial. There are multiple ways

to refer to a given concept (e.g. superclass vs. parent class), which is confusing to

those new to object oriented programming. Different developers use different terms,

and so we have tried to mention synonyms where appropriate. Deciding which terms

you will use is a personal choice.

Understanding Inheritance

Here is another important Java concept you’ll run into a lot: inheritance. Simply put,

inheritance means that Java classes (and therefore objects) can be organized into

hierarchies with lower, more specific, classes in the hierarchy inheriting behavior

and traits from higher, more generic, classes.

This concept is best illustrated by example. Let’s pretend we are developing a Java

application to simulate an aquarium. This aquarium has some fish in it. Therefore,

we might define a class to represent a fish. This class, called Fish, could include

some data fields (also called attributes, or class member variables) to describe a fish

object: species, color and size; as well as some of its behavior in the form of methods

(also called subroutines, or functions in procedural languages), like eat(), sleep(), and

makeBabyFish().

A special type of method, called a constructor, is used to create and initialize an

object; constructors are named the same as their class and may include parameters.

The following Fish class has two constructors: one for creating a generic Fish object

and another for constructing a specific Fish object with some initial data. You’ll also

see that the Fish class has two eat() methods: one for eating something random, and

another for eating another fish, which would be represented by another instance of

the Fish class:

1.

public class Fish {

2.

private String mSpecies;

3.

private String mColor;

4.

private int mSize;

5.

Fish() {

6.

// generic fish

5

7.

mSpecies = "unknown";

8.

mColor = "unknown";

9.

mSize = 0;

10.

}

11.

12.

Fish(String species, String color, int size) {

13.

mSpecies = species;

14.

mColor = color;

15.

mSize = size;

16.

}

17.

public void eat() {

18.

// eat some algae

19.

};

20.

21.

public void eat(Fish fishToEat) {

22.

// eat another fish!

23.

};

24.

25.

public void sleep() {

26.

// sleep

27.

};

28.

29.

public void makeBabyFish(Fish fishSpouse, int numBabies) {

30.

// Make numBabies worth of baby fish with Fish spouse

31.

32.

};

}

Classes can be organized into hierarchies, where a derived class (or subclass)

includes all the features of its parent class (or superclass), but refines and adds to

them to define a more specific object using the extends keyword. This is called

inheritance.

For example, the Fish class might have two subclasses: FreshwaterFish and

SaltwaterFish. These subclasses would have all the features of the Fish class, but

could further customize the objects through new attributes and behaviors or modified

6

behaviors from the parent class Fish. For example, the FreshwaterFish class might

include information about the type of freshwater environment lived in (e.g. river,

lake, pond, or puddle). Similarly, the SaltwaterFish class might customize the

makeBabyFish() method such that the fish eats its mate after breeding (as defined in

the super class) by using the override mechanism, like this:

1.

public class SaltwaterFish extends Fish

2.

{

3.

@Override

4.

public void makeBabyFish(Fish fishSpouse, int numBabies) {

5.

// call parent method

6.

super.makeBabyFish(fishSpouse, numBabies);

7.

// eat mate

8.

eat(fishSpouse);

9.

}

10. }

Organizing Object Behavior with Interfaces

In Java, you can organize object behaviors in what are called interfaces. While a

class defines an object, an interface defines some behavior that can be applied to an

object. For example, we could define a Swimmer interface that provides a set of

methods that are common across all objects that can swim, whether they are fish,

otters, or submergible androids. The Swimmer interface might specify four methods:

startSwimming(), stopSwimming(), dive(), and surface().

1.

public interface Swimmer

2.

{

3.

void startSwimming();

4.

void stopSwimming();

5.

void dive();

6.

void surface();

7.

}

A class like Fish could then implement the Swimmer interface (using the implements

keyword) and provide implementations of the swimming behavior:

1.

public class Fish implements Swimmer {

2.

// Provide implementations of the four methods within the Swimmer inter

face

3.

}

7

Organizing Classes and Interfaces with Packages

Class hierarchies, such as our fish classes, can then be organized into packages. A

package is simply a set of classes and interfaces, bundled together. Developers use

namespaces to uniquely name packages. For example, we could use

com.mamlambo.aquarium or com.ourclient.project.subproject as our package name

to keep track of our fish-related classes.

Wrapping Up

Wow! You’ve just embarked on a crash-course in Java for Android development.

We’ve covered a pretty intense amount of material here, so let things settle for a bit

before moving on to the next lesson of this tutorial series. In Lesson 2, we switch our

focus to the nitty-gritty details of Java syntax.

You’ve only scratched the surface of Java development for Android development.

Check out all the other great tutorials on Mobiletuts+ to dive deeper into Java and

Android development. Good luck!

Getting Started

As far as prerequisites go, we’re not going to make many assumptions about your

programming experience. We are going to assume you understand how to program

(perhaps in PHP, or Visual Basic or C++), but that you are unfamiliar with the

specifics of programming in the Java language. We’re not going to go into the details

of why you would want to do a for-loop versus a while-loop, but we will show you,

in Java, the syntax of both types of loops. Said another way, we aren’t going to teach

you to program; we’re going to provide you with clear examples of commonly used

Java language constructs and principles, while pointing out some Android-specific

tips and tricks.

What You’ll Need

Technically, you don’t need any tools to complete this tutorial but you will certainly

need them to develop Android applications.

To develop Android applications (or any Java applications, for that matter), you need

a development environment to write and build applications. Eclipse is a very popular

development environment (IDE) for Java and the preferred IDE for Android

development. It’s freely available for Windows, Mac, and Linux operating systems.

For complete instructions on how to install Eclipse (including which versions are

supported) and the Android SDK, see the Android developer website.

Now let’s look at some more helpful Java syntax.

8

Comments

Most programming languages allow for comments and Java is no different. You can

encapsulate any number of lines of text by beginning your comment with /* and

ending your comment with */. For example:

1.

/* MULTILINE

2.

COMMENT */

You can also provide comments after code on a single using //. For example:

1.

int x = 7;

// First variable called x equals seven

2.

int y = 8;

// Second variable called y equals eight

3.

int result = x + y;

// The result variable value should equal 15

Java also has a standard type of comments called Javadoc that can be used to not

only comment code, but also easily create code documentation. This topic is rather

large on it’s own, but here’s an example of what Javadoc comments looks like:

1.

/** This method does something interesting

2.

*

3.

* @param someValue processed and returned

4.

* @param option changes the type of processing done to someValue

5.

* @return The result of someValue being processed

6.

*/

7.

public int sampleMethod(int someValue, boolean option) {

//…

8.

9.

}

Variables

A variable is simply a piece of data. Java variables generally fall into two categories:

Primitive data types, like int, float, double, char, etc.

Java objects (as defined by a class definition)

Variables are used for different purposes. Sometimes variables are used to store

values that can change, or be modified, over time. For example, a variable called

counter might be incremented on occasion. Other variables, notably class variables

that remain the same for all instances of a given class, should be defined using the

static keyword. Other times variables might represent constants—these variables

should use the keyword final to show they do not change over time.

A variable is only valid within its territory, or scope. Variable scope is often

controlled by curly braces { }. When a variable is defined, it is valid within those

9

braces. If you try to access a variable outside of the braces, it will be undefined.

Class member variables in object-oriented languages are often called attributes. They

can also be called fields or properties.

Like other common programming languages, you’ve got your assignment operator,

the equals sign:

1.

int i = 5;

You’ve also got your arithmetic operators like +, -, *, /. Remember to use parenthesis

to force the order of operations as necessary:

1.

int result = (a + b) / c;

Finally, you have your typical unary operators, which allow you to modify a single

variable with a simple statement:

1.

iPositive++;

// increment by one; equivalent to iPositive = iPositive + 1;

2.

iPositive --; // decrement by one; equivalent to iPositive = iPositive - 1;

Note that the increment (++) and decrement (–) operators can be prefix or postfix,

meaning that the increment can be executed before or after any conditionals are

determined, if the item is used in a loop. Generally, we like to stick to postfix

statements, so code is more readable.

Primitive Data Types

Let’s look at some of the primitive data types available in the Java programming

language:

byte

o

short

o

A short variable is a 16-bit signed integer between -32,768 and

32,767. Again, often used for arrays.

o

An int variable is a 32-bit signed integer between -2,147,483,648

and 2,147,483,647. This is the most commonly used “number”

variable.

int

long

o

A byte variable is an 8-bit signed integer between -128 and 127.

Often used for arrays.

A long variable is a 64-bit signed integer between 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 and 9,223,372,036,854,775,807. Used

when the int data type isn’t big enough.

float

10

o

double

o

A double variable is a double-precision 64-bit floating point

number. Use this data type for decimal values.

boolean

o

A float variable is a single precision 32-bit floating point number.

A boolean variable has only two possible values: true and false.

Use this data type for conditional statements.

char

o

A char variable is a single 16-bit Unicode character.

Primitive types variables can be defined by specifying the datatype, followed by the

variable name, then an equals sign and an initial value. All Java statements end with

an semicolon. For example, the following Java statement defines a variable called

iVal, with an initial value of 1:

1.

int iVal = 1;

Like many other languages, you can define a zero-based array of a specific data type.

For example, the following defines an array of three integer values (first four powers

of 2):

1.

int[] aiPowersOfTwo;

2.

aiPowersOfTwo = new int[4];

3.

aiPowersOfTwo [0] = 1;

// 2^0=1

4.

aiPowersOfTwo [1] = 2;

// 2^1=2

5.

aiPowersOfTwo [2] = 4;

// 2^2=4

6.

aiPowersOfTwo [3] = 8;

// 2^3=8

Commonly Used Java Objects

The Java libraries provide a number of helpful objects for use with common data

structures. All objects are derived from the Object class. There are class counterparts

for all primitive data types. For example, the Integer class encapsulates an int value

and provides a number of helpful methods for manipulating integer data values. For

example, the following Java code instantiates a integer variable called iVal, then

creates an Integer object using a constructor that takes an integer, and then uses an

handle method available in the Integer class to extract a float variable equivalent.

1.

int iVal = 1;

2.

Integer integ1= new Integer(iVal);

3.

float f = integ1.floatValue();

11

Perhaps the most common object you’ll use in Android applications is the String.

The String class is used to encapsulate human-readable text characters, which are

often displayed to the screen. If you are modifying or building strings up from

smaller parts, you’ll also want to check out the StringBuffer and StringBuilder

classes.

1.

String strHello = new String("Hello World");

For a list of common Java data types, the Android reference includes documentation

for the java.lang package. You can also find the common input/output objects in the

java.io package.

For more complex data structures like lists, queues, stacks, dates, and times,

appropriate classes are in the java.util package.

Finally, Android applications rely on a number of helpful classes that define the

commonly used application components, like Activity, Application, Dialog, and

Service. These classes can be found in the android.app package.

Class Permissions and Access

You can control the visibility of a class as well as its variables and methods by

specifying an item’s access level. The access levels are: public, protected and

private. Generally speaking, if you want something to be accessible from outside a

class, use public. If a method or variable should only be accessible from the class

itself, use private. Use protected when the class or any of its subclasses need access.

For example, the following SillySensor class definition defines several variables and

methods with different access levels:

A class variable called sensorData, which is only visible within the class

A public constructor that can be called outside the class

A private method called calibrate(), which can only be called from within

the class itself

A protected method called seedCalibration(), which can be called from

within the class itself, or by a subclass

A public method called getSensorData(), which can be called from

anywhere, allowing for “read-only” access to the sensorData variable

1.

public class SillySensor

2.

{

3.

private int sensorData;

4.

public SillySensor()

5.

{

6.

sensorData=0;

12

7.

}

8.

private void calibrate(int iSeed)

9.

{

10.

// Do some calibration here

11.

}

12.

protected void seedCalibration(int iSeed)

13.

{

14.

calibrate(iSeed);

15.

}

16.

public int getSensorData()

17.

{

18.

// Check sensor here

19.

return sensorData;

20.

}

21. }

Conditionals

Java includes conditional statements, which can be used to execute snippets of code

if, and only if, certain conditions are met. Typically, a conditional statement involves

two sides. If the two sides are equivalent, the statement is true, otherwise it is false.

Java has all the typical conditional operators, such as:

== equal to, as in (a == b)

!= not equal to, as in (x != y)

> greater than, as in (z > y)

>= greater than or equal to, as in (q >= z)

< less than, as in (b < a)

<= less than or equal to, as in (a <= z)

And when you need to combine multiple conditional statements into a single larger

conditional test, you can use AND (&&) and OR (||):

((a==b)&& (a==c))

// true only if A is equal to B and equal to C

((a==b) || (a==c))

// true only if A is equal to B or equal to C

13

Java has bitwise operators (&, |, ^), shifts (>>, <<), and complement (~) operators as

well, should you need them. See the Java documentation for more details.

Now that you know how to craft a conditional statement, you can create conditional

code segments. The simplest form of a conditional code statement is the if()

statement:

1.

boolean condition = true;

2.

if(condition==true)

3.

{

// Execute this code only if condition variable is true }

If you want to provide alternative code to run if the condition is not met, then use the

else clause with the if() statement:

1.

boolean condition = true;

2.

if(condition==true)

3.

{

4.

5.

// Execute this code only if condition variable value is true

} else {

6.

7.

// Execute this code only if condition variable value is false

}

If you want to handle more than two cases, you can use cascading if-else-if-else

statements, like this:

1.

if(iVar==0) {

2.

// variable is zero

3.

} else if (iVar > 0) {

4.

5.

// variable is a positive number

} else {

6.

7.

// variable is a negative number

}

Switch Case Statements

When you have a number of different code paths possible that branch from a single

variable value, you can use a switch() statement. With a switch statement, you

supply the variable to check for and provide numerous options to execute for specific

cases. You can also supply a default option to execute if none other cases apply.

Each case can be terminated with a break statement. If a break statement is not

supplied, the code will continue executing into the next case statement.

1.

char singleChar = 'z';

14

2.

switch(singleChar) {

3.

case 'a':

4.

case 'e':

5.

case 'i':

6.

case 'o':

7.

case 'u':

8.

// singleChar is a vowel! Execute this code!

9.

break;

10. default:

11.

// singleChar is a consonant! Execute this code instead!

12.

break;

13. }

Loops

When you want to execute code repeatedly, or using recursion (heh, look that one up

if you don’t know what we’re talking about), Java has support for several different

kinds of loops.

To loop continuously provided that a statement is true, use a while() loop:

1.

int numItemsToProcess = 3;

2.

while(numItemsToProcess > 0)

3.

{

4.

// process an item

5.

numItemsToProcess--;

6.

}

If you want to evaluate the conditional loop expression AFTER the first iteration,

you can use a do-while loop instead:

1.

do

2.

{

3.

// check for items to process, update numItemsToProcess as required

4.

// process item, updated numItemsToProcess

5.

} while (numItemsToProcess > 0);

Finally, if you want to loop for a specific number of iterations, you can use a for()

loop. A for() loop has three parameters: the initial value, the terminating value, and

15

the incrementing value. For example, to execute a loop 100 times, printing the

numbers 1 through 100, you could use the following for() loop:

1.

for(int i = 1; i <=100; i++)

2.

{

3.

4.

// print i

}

Note: You can also use a break statement to get out of a while(), do-while() or for()

loop when necessary. You can also use a continue statement to skip the rest of a

current iteration of a loop and move on to the next iteration (reevaluating the

conditional expression, of course).

Passing By Value vs. By Reference

There are no pointers in Java. Ok, ok, go ahead and breathe a sigh of relief. Life is

hard enough without pointers mucking things up, right?

Ok, now it’s time to pay attention again. In Java, method parameters are passed by

value. However, when a method parameter is an object (that is, anything except a

primitive type), only a reference to that object is passed into the method [much like

pointers, sorry!]. Therefore, in order to modify the object passed into a given

method, you generally pass in the object reference, and then act upon it, which

modifies the underlying data of the object you passed in. You cannot, however, swap

out the object itself… Here’s a quick example:

Here, we have a class called Cat:

1.

2.

public class Cat {

private String mCatName;

3.

4.

Cat(String name) {

5.

6.

mCatName=name;

}

7.

8.

public String getName() {

9.

10.

return mCatName;

};

11.

12.

public void setName(String strName) {

13.

14.

mCatName = strName;

};

16

15. }

Now, let’s try to use this class and pass a Cat object into some functions and see

what happens:

1.

void messWithCat(Cat kitty) {

2.

3.

kitty = new Cat("Han");

}

4.

5.

void changeKitty(Cat kitty) {

6.

kitty.setName("Wookie");

7.

}

8.

9.

Cat haveKitten()

10. {

11.

Cat kitten = new Cat("Luke");

12.

return kitten;

13. }

Finally, let’s call these methods and see how they act upon Cat object instances:

1.

Cat cat1 = new Cat("Jabba");

2.

Cat cat2 = new Cat("Leia");

3.

4.

cat1.getName();

// Returns Jabba

5.

cat2.getName();

// Returns Leia

6.

messWithCat(cat1);

7.

changeKitty(cat2);

8.

Cat cat3 = haveKitten();

9.

cat1.getName();

// Returns Jabba – Note that object remains unchanged!

10. cat2.getName();

// Returns Wookie

11. cat3.getName();

// Returns Luke

Wrapping Up

You’ve just completed a crash-course of the Java programming language. While you

may not be ready to write your first Java app, you should be able to work through the

17

simplest of the Android sample application Java classes and determine what they’re

up to, at least in terms of the Java syntax of things. The first class you’re going to

want to look into for Android development is the Activity class. An Android

application uses activities to define different runtime tasks, and therefore you must

define an Activity to act as the entry point to your application. Now that you’ve got a

handle on Java syntax, we highly recommend that you work through a beginner

Android tutorial.

You’ve only scratched the surface of Java development for Android development.

Check out all the other great tutorials on Mobiletuts+ to dive deeper into Java and

Android development. We highly recommend the following beginning Android

tutorials: Introduction to Android Development by Gyuri Grell and Beginning

Android: Getting Started with Fortune Crunch to begin dabbling in Android

development. Good luck!

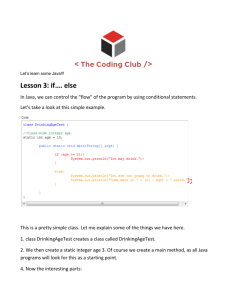

This quick lesson in our Learn Java for Android Development series shows you how

to conditionally check the type of an object using the instanceof keyword in

Java.

Basic Conditionals

We talked about many of the basic Java conditional statements in the Learn Java for

Android Development: Java Syntax tutorial. For example, Java provides all the

typical conditional operators one might expect, including those to check for equality,

inequality, greater than, less than, etc.

Here’s some Java code that checks the value of a numeric variable (called iVar) and

provides different code paths depending on whether the value of iVar is zero,

negative or positive:

1.

if(iVar==0) {

2.

// variable is zero

3.

} else if (iVar > 0) {

4.

5.

// variable is a positive number

} else {

6.

7.

// variable is a negative number

}

Using instanceof in Conditional Statements

Now let’s look at a specific Java feature you can also use in conditional statements.

Because Java is a fully object oriented language, you can also test if an object is of a

specific type (an instance of a specific class) conditionally using the instanceof

18

keyword. The instanceof keyword is a Boolean operator, used like a regular

mathematical Boolean conditional operator to generate a true or a false result.

Let’s look at a quick example. Let’s assume we have a parent class called Fish,

which has two derived subclasses: SaltwaterFish and FreshwaterFish. We could use

the instanceof keyword to test if an object is an instance of a specific class (or

subclass) by name:

1.

SaltwaterFish nemo = new SaltwaterFish();

2.

if(nemo instanceof Fish) {

3.

// we’ve got some sort of Fish

4.

// could be a Fish (parent class), or subclass of some kind, like

5.

// SaltwaterFish, or FreshwaterFish.

6.

7.

if(nemo instanceof SaltwaterFish) {

8.

// Nemo is a Saltwater fish!

9.

}

10. }

Using instanceof in Android Development

So, when it comes to Android development, when is the instanceof feature

useful? Well, for starters, the Android SDK classes are organized in typical object

oriented fashion: hierarchically. For example, the classes such as Button, TextView,

and CheckBox, which represent different types of user interface controls, are all

derived from the same parent class: View. Therefore, if you wanted to create a

method that took a View parameter, but had different behavior depending upon the

specific type of control, you could use the instanceof mechanism to check the

incoming parameter and determine exactly what kind of view control had been

passed in.

For example, the following method takes a View parameter, allowing you to pass in

any type of View, but specifically singles out TextView controls for special

processing:

1.

void checkforTextView(View v)

2.

{

3.

if(v instanceof TextView)

4.

{

5.

6.

// This is a TextView control

} else {

19

7.

// This is not a TextView control

8.

9.

}

}

In this example, we might continue by making a call to a method that is only valid

for a TextView object and not the generic View object—in which case, we would

likely cast the View parameter to a TextView prior to making such a call. If,

however, we wanted to make a call that is available in all View objects, but behaves

differently in TextView objects, there is no need to test for this. Java will handle

calling the appropriate version of the method specific to TextView. This is one of the

great features of object-oriented programming: the most appropriate version of a

given method is called.

Conclusion

In this quick lesson you have learned how to use the instanceof Java keyword to

check the type of an object at runtime and provide conditional code paths based on

the result. This is a handy Java feature that Android developers often rely upon, since

the Android SDK is organized hierarchically.

20