The Origins of the “History of the Turkish

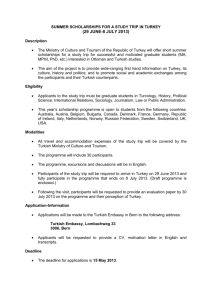

advertisement

Teaching a State-Required Course: The History of the Turkish Revolution Dilek Barlas Associate Professor Koç University Department of History Sarıyer 34450 Istanbul, Turkey dbarlas@ku.edu.tr Telephone no.: 00902123381408 Fax no.: 00902123383760 Yonca Köksal Assistant Professor Koç University Department of History Sarıyer 34450 Istanbul, Turkey ykoksal@ku.edu.tr Telephone no.: 00902123381710 Fax no.: 00902123383760 1 Introduction The “History of the Turkish Revolution” course has been a mandatory course in higher education since the early years of the Turkish Republic, and it serves a specific function: to introduce young citizens in a positive way to the Turkish Revolution and to the fundamental principles of the Republic. When the course was adopted, it had a general purpose of creating loyal citizens to the nation-state as well as a particular purpose that is breaking away from the Ottoman past. Although there have been changes in the content and teaching methods of the course since the 1930s, its purpose of creating loyal citizens has remained the same. In fact, creating citizens from royal subjects was the case in many European countries mainly in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century during the nation-state formation processes. But the Turkish case is unique in the sense that the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish nation-state in the first half of the 20th century had still its continuing effects in Turkish education in the 21st century.1 Thus, the first aim of this paper is to analyze history and evolution of the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course in order to understand the durability and continuation of the course in a changing world context. This emphasis on the dominance of nation-state over individual creates a contrast with the philosophy of Liberal Arts education which aims at developing the student’s rational thought, free will and intellectual capabilities. Moreover, methods of teaching the course are problematic in a Liberal Arts Program. Teaching a state-required course creates several problems, such as lack of student interest, students’ prejudices about the course as a result of having taken the same course during their secondary education, and limitations set by the state. In order to overcome these prejudices and make the course attractive to students, on the one hand, we have developed ways to include the proposed content in the Liberal Arts 2 program of Koç University.2 On the other hand, we have adopted teaching methods from the New History approach, such as comparative history and history from below. In this way, the course provides an opportunity for our students to familiarise themselves with the history of their own society and provokes students to think about contemporary problems of Turkish society. Thus, the second purpose of this paper is to discuss challenges of teaching this course in a Liberal Arts Program aimed at analytical and critical thinking and to offer solutions using new methods in history. In the following section, we will explore the history of this course in the Turkish university curriculum. We will first analyse the history of its formation and its development in comparison with the Soviet case. In fact, in the Soviet Union, where the ideological indoctrination of the younger generation was even more important than in Turkey, the concept of teaching a course on the Russian Revolution was quite different. While the Turkish Revolution course has been taught such that it covers the same subjects in secondary and higher education, the Soviet education covered different subjects in secondary and higher education, as we will discuss below. We are comparing Turkey and the Soviet Union because in both of these countries new systems surviving for decades were established in rejecting their past. While socialism had collapsed in the Soviet Union in 1989, the Kemalist Republican system in Turkey is still alive. Since the Turkish state still requires this course to be taught at Turkish universities today, the paper will also discuss the methods and techniques that we have developed in teaching this course in order to respond to the needs of undergraduate students of the twenty-first century. Then, we will explain the methods we have employed in the classroom, with an emphasis on the new theoretical paradigm in history, as well as our experiences with teaching the course at Koç University. 3 The Origins of the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course Major state transformations such as social revolutions and revolutions from above can also be considered cultural revolutions since the state is not simply an organ of coercion and economic power. “Through forms, rituals and routines, state activities attempt to regulate social identities and form constitutive regulation… Fundamental social classifications, like race and gender, are enshrined in law, embedded in institutions, routinized in administrative procedures and symbolized in rituals of the state.”3 These attempts of state regulation over culture can hurt as much as they help. Using cultural symbols, mythologies and rituals, state rulers can invent traditions to immortalize the nation and appeal to their citizens.4 However, the same policies can define and stigmatize some groups as the “other” while imagining the nation.5 The state activities can encourage some while suppressing, marginalizing, eroding and undermining others. Schooling plays a major role in cultural revolutions. National education becomes a means for creating citizens in line with state policies and ideologies. In the late 19 th and early 20th centuries, the Ottoman state started to invest in state education, but the literacy rate was around 10-15% at the time of the foundation of the Turkish Republic. The previous imperial subjects were in need of socialization to the concept of Turkish nation and Turkish citizenship. Thus, the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course became one of the means in Higher Education to create citizens, and its foundation and evolution was related to the general developments in National education and in History education in particular. In fact, in 1994, the Minister of National Education Nevzat Ayaz wrote that in the organizational structure of the state, there were only two ministries that have the term “national” in their titles: The Ministry of National Defense and Ministry of National Education.6 The idea of 4 national education became a central idea for the new Turkish Republic, and the Ministry of Education was founded on 2 May 1920, only ten days after the formation of the Grand National Assembly.7 In the midst of heavy fighting in 1921, the Education Congress was met in Ankara to “give a national direction to education”.8 In 1923, public education became mandatory for both boys and girls. In 1924, the Law of Unification of Instruction (Tevhid-i Tedrisat Kanunu) was passed, and it has formed the basis of all educational laws. The origin of the course on “the History of the Turkish Revolution” dates back to the early decades of the foundation of the Republic. This was an important time period when the new Turkish state necessitated the consent and support of its citizens so as to consolidate its rule and apply its reform policies. According to Christoph Neumann, with early Turkish Republican era, the main paradigm was to form Turkish history thesis in an attempt to provide an identity to the new state.9 Denial of the Ottoman and Islamic past and an emphasis on linkages with ancient civilizations in Anatolia and Turks in Central Asia became the major concerns of history education.10 History education served a special function in this context, because critical subjects such as Ottoman history and the history of the War of Independence (1919-1922) had to be taught in a way to gain the support of the citizens for the new regime.11 In other words, the new Turkish state aimed at creating loyal citizens from imperial subjects.12 The implementation and developments in the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course should be considered part of the attempt to “raise citizens who are committed to Atatürk’s principles and revolutions, and to Atatürk nationalism… who embrace, protect, and develop the national, moral, spiritual, historical and cultural values of the Turkish nation”, with the words of Ayaz.13 Even though there were earlier attempts to show the importance of education, it is not surprising that steps towards the teaching of a national history were taken only in 1929 when the new Republican regime became more confident after the success of some political 5 reforms. The abolition of the sultanate (1922) and the caliphate (1924) and the formation of the Republic (1923) were central to the transformation from the Ottoman Empire to the new Turkish nation-state. In 1925, the Republican government did not only pass the Law on the Maintenance of Order but also closed down the religious shrines and the dervish convents. In 1926, the European calendar and the Swiss civil code were adopted. By 1927, Atatürk already felt more secure and gave his “great speech” (nutuk) which provided his interpretation of the War of Independence and against what great odds it was fought and won.14 In 1928, the replacement of the Arab script by the Roman alphabet and the removal of the article in the constitution describing Islam as the religion of the state further aimed at giving a modern and secular outlook to the minds and bodies of the citizens. Secular reforms of the Republic were to be taught to public trough schooling. As a next step, in 1929, experts selected by the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, started to work on civic education and national history. The Republican leadership believed that civic education and national history would facilitate the formation of a Turkish nation-state, since the Ottomans had neglected these two domains. They were convinced that “these two cultural movements [civic education and national history] are quite significant for the revival of national essence and consciousness.”15 In Afet İnan’s terms, this was the beginning of “a wide period of historical research.”16 In fact, Büşra Ersanlı Behar defines this kind of historiography as a “missionary historiography”. Historians such Afet İnan represented “a citizenship-history school” which became the torchbearer of nationalist historians and formed “a national history front” in the name of science.17 Therefore, the idea of teaching a course on the Turkish Revolution emerged in the 1930s. Moreover, the repercussions of the 1929 world economic crisis led the Turkish political leadership to give ideological shape to the new Republic. 18 In Europe, ideologies such as fascism, liberalism and socialism prevailed. In addition, the ruling elites were 6 concerned with keeping the sovereignty of the new state when political and military rivalry dominated Europe. At the same time, the Turkish leadership, aware of the competing ideologies, aimed to prove the uniqueness and success of the Turkish revolution to Turkey’s citizens. Within this context, the Turkish intellectuals and political leaders started discussing étatism as an alternative way to the existing political systems in Europe and a way to prevent their domination in Turkey. For the Turkish political leadership, étatism was not socialism because it considered private initiative in the economy as essential. It was not liberalism either because the state was responsible for the national economy. Etatism was a system which aimed at satisfying the important needs of the country as soon as possible.19 In the early 1930s, the Turkish leaders were already convinced that they could create republican, nationalist, étatist, populist, revolutionary, and secular citizens in the new nationstate. One of the most important ways to reach this goal was to create historical consciousness among the youth. In 1930, copies of a book entitled The Main Features of Turkish History were published, and it became a guidebook for future history books.20 In 1933, the Institute of the Turkish Revolution was established at the University of Istanbul in order to teach a course on the history of the Turkish Revolution. According to the Minister of Education of the time Reşit Galip, the University was to shape the ideology of the Turkish Revolution.21 Between 1934 and 1942, the key political leaders of the Republic — namely, Yusuf Hikmet Bayur, İsmet İnönü, Recep Peker, Mahmut Esat Bozkurt, and Yusuf Kemal Tengirşenk — gave a series of lectures on the revolution’s political, legal, economic, and institutional aspects at the institute.22 The first lecture was given by the Minister of Education, Yusuf Hikmet Bayur, who explained the different stages of the Turkish Revolution. In his introduction, he pointed out that the military and political aspects of the revolution started with the War of Independence against the Allied powers. Once the Turkish Republic had been founded, the revolution turned 7 to legal issues. After that, the most important aspect was the economic one. In fact, in the second part of his lecture, in which he referred to the Ottoman past, he emphasised how the Ottomans became economically dependent on foreign powers because of the capitulations. Bayur added, “the Turkish people of Anatolia had to cope with this economic burden.” 23 For that reason, he believed that the success of the Turkish Revolution at that time was mainly related to the abolition of the Caliphate and the capitulations. Therefore, he divided the Turkish Revolution into three sub-periods: the military and political period (1914-1923), the legal period (1923-1926), and the economic period (1929-1934). In this process, “the Turkish people formed the body and Atatürk was the head of the Revolution”; without Atatürk, the Turkish Revolution could not have succeeded.24 M. Esat Bozkurt followed Bayur. He discussed what revolution meant in general, referring to various revolutions such as the socialist and national socialist ones. He also discussed what philosophers (such as Kant, Nietzsche and Marx) and Turkish intellectuals (such as Mithat Paşa and Namık Kemal) had thought about revolutions. Having presented these general issues, he compared Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the Turkish Revolution to Lenin and the Russian Revolution. He argued that Lenin was not a real man of the pen or a man of action; however, Mustafa Kemal was both.25 Moreover, he argued that people were able to make revolutions, but that they needed to be oriented by leaders. For instance, he stated that the Turkish nation was born again after World War I thanks to its great leader, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.26 Prime Minister İnönü’s lecture was along the same line as Bayur’s and Bozkurt’s. According to him, the Turkish Revolution started on two fronts, as a war against the invading powers and a war against the Ottoman system.27 According to İnönü, the Turkish Revolution was the liberation of the Turkish nation, and this liberation was aimed at making the Turkish nation an eminent society. But in order to reach this goal, İnönü believed that they should not 8 adopt “dogmatic viewpoints.”28 Like Bozkurt, he believed that Turkey should not opt for socialism or fascism. Contrary to these ideologies, the Turkish Revolution was to be “a dynamic and an enduring process.”29 He also stated that to understand and love the Turkish Revolution meant to understand Mustafa Kemal and follow his principles. As the astute reader will notice, these lectures were given in 1934, at the end of the economic period as defined by Bayur. This was the year when étatist measures were already implemented and the First Industrial Plan put into effect. By 1934, étatism was already accepted as an economic policy as well as a political strategy for Turkey. For that reason, the political leadership aimed to persuade the audience that the Turkish Revolution was authentic and different from “dogmatic viewpoints” (such as socialism), in İnönü’s terms. To prove this, these intellectuals in their lectures compared the nature of the Turkish Revolution to that of other existing political regimes around the world. By drawing comparisons with the experiences of others, they aimed to prove that the new system in Turkey was not a copy of another system, but, in fact, a “third way.”30 The lectures of Tengirşenk and Peker mainly discussed economic changes during the Turkish Revolution as well as political systems, including the Turkish one. Tengirşenk, like the others, first presented the historical background of the Ottoman economic system. In this context, he mainly underlined how the Ottomans became dependent on foreign powers because of the capitulations.31 After discussing the economic and political collapse of the Ottoman Empire, he dealt with the foundation of the new Turkish state. The Industrial Revolution in Turkey occupied the largest part of his lecture on the economic aspects of the revolution. After giving examples of étatist measures undertaken in Turkey, he argued that the development of a national industry would make the Turkish people forget the troubled times of the Ottoman Empire. 32 9 Peker discussed socialism, fascism and liberalism not from a philosophical point of view, as had Bozkurt, but from a political one. After giving examples of such regimes around the world, he defined the Turkish system: first, the Turkish Revolution was not a copy of another system, as the Ottoman Constitutional regime of 1877 had been.33 Moreover, the Turkish Revolution was not based on liberalism or class revolution. In criticizing all the existing regimes, he argued that the Turkish Republic opted for a national state instead of a liberal one, for a single-party system with a chief as the head instead of a multi-party one, and for a national economy instead of a liberal one. He believed that the Turkish Revolution would have universal effects. In summary, all of these leaders criticised the Ottoman past in their lectures. In doing so, they were also critical of the foreign powers that had rendered the Ottomans dependent on them. They all argued that the Turkish people, as a reaction to the past, had started the revolution under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) and had been successful until the mid-1930s. Moreover, they believed that the revolution had not yet been completed. Turkey had not copied any of the existing systems around the world, but had developed an authentic regime or a third way. To prove this point, information was provided about different political ideologies (such as socialism and fascism), and comparisons were made between these ideologies and Kemalist principles. In this early decade, the course encouraged analytical thinking by making comparisons and situating the Turkish Revolution in a global context. However, the aspect of social engineering was quite visible: through analysis and comparison, the course aimed at achieving the students’ agreement on the uniqueness and success of the Turkish model. In contrast to the argument of the revolution’s uniqueness, one could argue, Turkey was very much influenced by the Soviet case, in the sense that it took as a model the first Soviet Five-Year-Plan. There were some further similarities between Turkey and the Soviet 10 Union. The latter in 1917 and the former in 1923 established new systems, rejecting respectively the history of the Russian and the Ottoman Empires. Since the concern of the Soviet and Turkish leadership was to defend their regimes against opposition within the country and against the Allied powers, they had to wait until the late 1920s and 1930s to consolidate their regimes. As in Turkey, “the Five Year Plan (1928) required rapid expansion of schools, improvement of knowledge about society, and intensification in ideological indoctrination of students” in the Soviet Union.34 Dorotich adds, “history had a very significant role to play” within this process.35 Furthermore, Brandenberger and Dubrovsky have argued that the party’s attitude towards history-teaching in the Soviet Union changed especially in the early 1930s, when official priorities expanded from a focus on the mechanical aspects of industrialization to the training of a loyal, capable work force.36 Other scholars who specialise in Russian history, such as Laugla, have written that there was a shift from the earlier political education (of the 1920s) that aimed at developing a basic value commitment to the ideology, to an education that emphasised the disciplinary aspect of the role of the loyal Soviet citizen (in the 1930s).37 In the early 1930s, the Soviet leadership understood that the purpose of Russian and Soviet history “was to catch people’s imagination and promote a unified sense of identity that the previous decade’s internationalist proletarian ideology had failed to stimulate.”38 In 1931, the People’s Commissariat of Education reintroduced history as an independent classroom subject. Moreover, in 1934, a Politburo committee criticised the teaching of history in Soviet schools as too sociological and called for more political history instead.39 Clearly, the pattern of history teaching in Turkey and in the Soviet Union followed a similar chronological order. Yet, the way in which the history courses on the existing regimes were taught was quite different. As we will discuss in greater detail below, the History of the 11 Turkish Revolution has been taught in Turkey at all educational levels, from elementary to undergraduate education. However, in the Soviet Union “the Central Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars resolved to introduce into primary schools and into the 1st grade of the secondary schools an elementary course of the history of the U.S.S.R.” 40 In fact, in 1934, there was a resolution of the Central Committee “on the teaching of Civil History in the schools of the USSR,” and from 1937 on, A Short Course on the History of the USSR was used as a textbook in secondary education.41 As far as the undergraduate level was concerned, a course on the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) was taught instead of a course on the History of the USSR.42 Changes in the Course Over Time In the 1940s, in Turkey, the aim was to organise a course on the Turkish Revolution, which would be taught comprehensively in universities. The Minister of Education, Hasan Ali Yücel, summarised this aim as follows: “the Revolution was to be taught in a scientific way to the new generation, who were the future of the country.”43 In order to reach this goal, in 1942, an “Institute of the History of the Turkish Revolution and the Republic of Turkey” was founded and Professor Enver Ziya Karal was appointed as its head. The institute prepared a draft suggesting that the course titled the “History of the Turkish Revolution and the Regime of the Republic of Turkey” (Türk İnkılâbı Tarihi ve Türkiye Comhuriyeti Rejimi) would be given in two parts: The first should be entitled “The History of the Turkish War of Independence and the Turkish Revolution (1918-1938),” and the second part should deal with “The Regime of the Republic of Turkey.”44 Contrary to the 1930s, the comparative thematic approach of the study of the Turkish Revolution was abandoned, and the Republican period was studied in a chronological order. The comparison of the Republic of Turkey with the Ottoman Empire and with other existing 12 systems around the world was ignored.45 In fact, one of the main reasons for these changes was the growing political polarization in Turkey in the 1940s. Even though Turkey was not involved into the Second World War, the ideological effects of the war were of concern for the Turkish political leadership. The best way to avoid the effects of ideologies such as socialism was to indoctrinate the Turkish youth with Kemalist principles.46 The course continued to be taught with minor changes in the 1950s. After the 1960 military coup, the course had to be taught for two semesters in all universities. In 1968, the name of the course was changed to the “History of the Turkish Revolution” (“Türk Devrim Tarihi”).47 This was a symbolic change, since the earlier usage of inkılâb implied evolution and revolution at the same time, while the new word devrim clearly evoked revolutionary aspects.48 One could also argue that the ascendancy of the 1960s leftist movements around the world and in Turkey affected this name change. Another effect of the 1960s can be observed in the textbook prepared by Enver Ziya Karal for this course, printed in 1971. This was an attempt to introduce recent history including developments until 1965.49 The most radical change in the approach and content of the course on the Turkish Revolution occurred during the military regime in the 1980s. The course was renamed as “Atatürk’s Principles and the History of the Turkish Revolution” (“Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâb Tarihi” in 1981.50 The main objective of the state was to overcome the political opposition that had existed prior to the military regime. The 1980 military coup was in fact an attempt to control social movements, and especially leftist organizations, since the spread of socialism was seen as a threat in the Cold War era. The purpose of creating loyal citizens became more visible with the policies of the military regime. The military regime aimed to prevent further ideological polarization in the universities by all means. As a first step, the Higher Education Council (Yüksek Öğretim Kurulu, YÖK) was founded in 1982 under the guidance of the military regime, in order to institutionalise the 13 government regulation of and interference in university affairs. The military regime wanted to have central control over higher education, thought to be lacking central planning. The idea was also to control youth movements, by having direct state control over universities.51 As a second step, YÖK required the formation of Institutes of the Turkish Revolution in six Turkish Universities.52 These institutes were responsible for teaching the History of the Turkish Revolution to graduate students as future instructors of the course. For this purpose, these institutes had to have graduate-level education. In the remaining universities, either centres for teaching the course on the Turkish Revolution were established, or other relevant departments — such as history, political science and sociology—taught the course. YÖK categorised the purposes and limitations of the course under four headings: to provide adequate information about the Turkish War of Independence, the Turkish Republic, and Atatürk’s reforms and ideas; to give accurate information about threats to reforms and to the regime; to unite the Turkish nation; and to raise Turkish youth based on the principles of Atatürk.53 This list shows that the purpose of the course was not to provide information from various angles about the historical events of the Turkish Revolution; rather, it was to teach a certain interpretation of the Turkish Revolution, and it aimed at teaching Kemalist ideology to university students. In other words, the goal was to form citizens loyal to the Kemalist Republic. In order to achieve these four principles, YÖK exercises control over the content and length of the course. YÖK requires that the above mentioned headings have to be acknowledged in the course and that the time period from the start of War of Independence (1919) to the death of Atatürk (1938) had to be covered in the course content. There is some flexibility of adding other topics and time periods after covering the required subjects. YÖK did not force the use of single textbook but recommends textbooks in line with the required 14 curriculum. YÖK representatives have a right to interview faculty teaching the course about the content and reading materials during their annual visits to universities.54 In 1989, YÖK prepared a textbook and suggested for the usage of the institutes to teach the course. This book, which is still widely used, begins with the definition and purposes of Atatürk’s principles and the revolution and continues with a short summary of the factors leading to the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century. It focuses on the Independence War, the formation of the Turkish Republic, Turkish foreign policy, and the reforms in law, education, culture, economy and health until 1938. A specific section is dedicated to the geopolitical location of Turkey and current internal and foreign threats to the Turkish Republic, since preventing the spread of radical movements among youth is considered a major aim of this course.55 As can be seen from the course content required by YÖK, the course focuses on a limited time period, mainly between 1919 and 1938, with a brief summary of nineteenthcentury events. Compared to the 1930s, the course content and teaching methods have changed significantly, while the aim of creating loyal citizens has remained the same. In the 1930s, comparisons to and analysis of other political ideologies in Europe were made in order to prove the uniqueness of the Turkish Revolution. After the 1980 military coup, these aspects were removed from the course, and memorization of events and great men dominated instead. Moreover, the course was taught for two hours per week for four years until 1991. Since 1991, YÖK has required teaching the course on the Turkish Revolution for a minimum of 60 hours within one academic year. Universities adhere to this minimum requirement and some universities teach it as a non-credit course. 56 15 Dilemmas and Challenges Related to Teaching the Course Teaching the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course is challenging because of difficulties rising from both general issues related to history education in Turkey and teaching this course in a Liberal Arts program of a university in particular. University students are exposed to a certain type of history education in their primary and secondary education whose curriculum was controlled by the Ministry of National Education. 57 Among the major problems in history education is the lack of attention to international context and world history while increasingly emphasizing Turkish and Islamic past in the secondary school textbooks since the 1990s.58 In addition to the content, there are issues about how the “nation” was constructed in history education. Wars, conquests and military conflict are glorified while peaceful coexistence of differences is not discussed in the history textbooks.59 History teaching in primary and secondary education follows a traditional approach that prevailed in the nineteenth and early twentieth century: Courses are organised chronologically (not thematically), and students are required to memorise events, dates and the names of great men without looking at processes and causes that bring these events into being. Major transformations such as the start of a century were taught in a single event such as Mehmed II conquering Istanbul in 1453 and the French Revolution in 1789. Lack of interest in analyzing processes and cause-effect relations prevents the development of analytical skills of students since rote-memorization of events is the key for success. These earlier experiences with history courses in secondary education have been a challenge for most university students in the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course. Students continue memorizing important events and dates without critical questioning. They learn about the same subject using the same didactic methods since the elementary school. In addition, repetition of the same issues over time starting with their secondary education 16 results in dislike and losing interest in the topics discussed in the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course at the university level. Evaluation of student performance is based on how well students can regurgitate memorised information, instead of encouraging students to evaluate and analyse events and themes.60 The adoption of the same methodology for the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course makes it difficult for university students to enjoy the course. Moreover, in the 1990s the rise of Kurdish and Islamist proclivities among university students pointed to the shortcomings of the course and led to the questioning of its format and content. Although the purpose of the course has been to provide loyalty to the regime and to Kemalist principles, over time YÖK has recognised shortcomings of the course in achieving these purposes. Between 1997 and 1998, six meetings brought together academics from Atatürk Institutes and YÖK members in different universities. These meetings explained the purposes of the course, listed the problems related to teaching the course, and offered a number of solutions. In the 1998 Hacettepe University meeting, one of the speakers defined the purpose of the course as follows: … to ensure that the new generations embrace Atatürks’s principles and reforms and to provide youth with knowledge and equipment that would awaken the youth about dangerous and separatist ideas and actions. While the students are interpreting contemporary national and international events from the angle of the recent past, they will realise that they are the heirs of a rich history.61 Other speakers also acknowledged that this course was an ideological antidote which would provide loyalty to the state.62 Having stated this important function, participants also voiced problems concerning teaching the course. The Hacettepe University meeting was an example of general concerns of instructors teaching it. Lack of interest among students, prejudices of students as a result of 17 their elementary and secondary education, a lack of qualified instructors, and a lack of adequate visual and published teaching material, especially in smaller universities, were stated as the common problems. Complaints also included the need to develop new teaching methods, since the current program focused only on political history and chronology. As a solution to these problems, an interdisciplinary approach focusing on history, society, culture, economy and politics was suggested. Some participants argued that teaching Ottoman history since the first modernization attempts in the late eighteenth century was necessary to understand the formation of Atatürk’s ideas and policies. Even though everyone agreed on the need to acknowledge the Ottoman past, there was disagreement about the extent to which it should be covered. Some participants argued that too much coverage of Ottoman history would prevent instructors from devoting sufficient time and effort to the Turkish Revolution. The participants also agreed on the need to acknowledge the current political, social and economic situation and to expand the curriculum to contemporary events in Turkey and around the world. A comparative approach — that is, a comparison of the Turkish Revolution with other revolutions and ideologies — was also suggested by some participants in order to show the strength of Kemalist ideas.63 Although these meetings produced important suggestions for improvement, the course’s content and teaching techniques have not improved much since then. Surveys conducted in several universities (such as Gazi and Hacettepe Universities) show that students had similar complaints in 2005 and 2006: the lack of coverage of current issues, and the need to memorise chronology without comprehension.64 In fact, universities continue to follow the course content suggested by YÖK.65 A quick look at commonly used textbooks also reveals trends similar to the ones shown in YÖK’s textbook. A very brief introduction on the reasons for the Ottoman Empire’s decline, followed by a focus on the Independence War, the formation of the Republic and 18 Atatürk’s six principles are the topics common to the frequently used textbook by Ahmet Mumcu and the YÖK textbook. Mumcu’s textbook covers a longer chronology and includes the transition to multi-party democracy in the 1950s.66 Karal’s above-mentioned book expands the chronology to include the 1960s.67 Lack of interest in current events, inadequate coverage of the Ottoman past, lack of comparisons with other revolutions, and an inability to situate the events in a global context are the common characteristics of these texts. Theory and Methods in Teaching History Teaching methods in history are closely related to changes in theoretical paradigms. In the last twenty to thirty years, there has been a shift from a traditional paradigm to a new approach that has radically re-conceptualised the key concepts of history.68 The older writings of history at the dawn of the twentieth century were concerned with politics and studied the activities of states and great statesmen. History evaluated events from the standpoint of the upper classes. War, diplomacy and high politics were the dominant subjects. History-writing relied on state documents, such as treaties, letters and the memoirs of the ruling elites. It was believed that the documents told the truth, and a simple narration based on these documents would be enough for historical analysis. As the authors of these documents -- kings, emperors, bureaucrats and the like -- were the major players, they, as great men, made history. 69 Because of its singular focus on politics, the traditional paradigm does not include social history which concerns the daily lives of ordinary people. This approach teaches facts as objective given events and presents a narrative without paying attention to causal linkages. It uses an abundance of evidence, mainly state archives and written documents, in an attempt to study politics.70 Since this traditional approach focuses almost exclusively on great men and a narration based on 19 documents, it cannot see the importance of broader factors at play, such as the social, economic and political structures that constitute recurrent patterns of relationships in different aspects of life. Influential historians of this approach — such as Leopold von Ranke, a famous representative of the German school, and Edward Gibbon, of the British school — shared the same lack of concern for broader changes in general conditions. Gibbon explained the fall of the Roman Empire as resulting from changes in the relations of the ruling class and the loss of “civic virtues” among the elites. Ranke emphasised human agency, refuted the role of general theories cutting across space and time, and concerned himself with the interpretation of primary documents about specific periods. This lack of interest in general theories, structures and ordinary people led historians to focus on details without seeing the general picture of the time they studied. The uniqueness of each case, the individual, and the document were emphasised, and comparisons that could lead to a broader analysis of general conditions were ignored. The New History emerged in reaction to the traditional approach, starting with Marc Bloch’s writings and developed by the Annales School in the 1960s and 1970s.71 At that time, the debate of structure versus agency had been a long-standing issue in the social sciences. In an attempt to close the gap between history and the social sciences, the New History shifted the focus from great men to long-term changes in social, economic and political conditions. Rather than offering a particularistic interpretation of documents, its purpose is to reach a general understanding of change in different aspects of life. The new approach does not simply summarise events. Instead, it attempts to explain structural changes over time and focuses on causal analysis. How and why certain events influence subsequent events in the longue durée is the most important question for the new type of historical analysis. Attempts to define causal linkages in long-term structures 20 emphasise the importance of comparative studies. Fernand Braudel’s The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II is a major example of studying causal linkages in the connected world of the Mediterranean and how trade between different regions influenced politics, culture and economy across the region. Therefore, instead of focusing on single area, Braudel studied the Mediterranean as a whole and compared different regions over time.72 The New History expands the focus from politics to other areas of life. Society, culture, economy and politics are studied as different aspects of social structures in order to define recurrent patterns. It considers all human activity worthy of study, including the lives of ordinary subjects, instead of focusing on the state and ruling groups. Thus, peasants, beggars and women have become some of its subjects. This interest in “history from below” provides new sources of evidence for historical research. In addition to state documents, statistics (trade and population figures) and oral history (myths, folkloric tales and memoirs) have become sources of evidence.73 In contrast to the traditional paradigm’s claim of objective reality, the New History considers reality socially or culturally constituted. Instead of telling how events actually happened, the New History is aware that present beliefs and viewpoints shape the description of past events. This approach enhances our understanding, by presenting opposite viewpoints. A Brief Note on Experiences of Teaching the Course in a Liberal Arts Program Differences between the traditional paradigm and the New History also reflect the difficulty of fulfilling the state’s expectations in teaching the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course. The course content required by YÖK represents the traditional approach. It focuses on politics in terms of military conflict and state administration, demands history 21 from above, excludes the history of ordinary people, and studies the great statesmen and world politics of the time. Atatürk and his close circle of political leaders form the main unit of analysis. Their actions are presented as the main determinants of state administration. This traditional approach presents the official history of the Turkish Revolution as ultimate truth and does not provide any alternative readings of Turkish history. The purpose of the course is to show the uniqueness of the Turkish case within the world of competing ideologies. Kemalist ideology and the Republic are presented as a result of peculiar historical circumstances and the strong will of a “unified nation.” In this framework, there is no room for comparisons with other revolutions. The importance of the global context and comparison with other revolutions which existed in the 1930s to prove the uniqueness of the Turkish Revolution disappeared later.74 A handful of universities have started to experience with new curricula, teaching materials and methods in the recent years as a result of an increasing need to improve the course. Among the universities which have programs similar to Liberal Arts curricula, Boğaziçi, Sabancı, METU and Bilkent extended the course content to cover the time period from the19th century Ottoman Empire to the recent developments in Turkey. At Bilkent University, the-two credit course has been taught in two semesters to sophomores, and covers the time period from the early 19th century to 1980. Its focus is on political and diplomatic history with domestic and foreign developments.75 At Sabancı University, the-two credit course for sophomores begins with “a review of the pressures building in the Ottoman Empire through the 17th and 19th centuries and covers the time period until transition to parliamentary pluralism in 1946-50”.76 Political, intellectual and social history in explaining domestic developments are emphasized. At Boğaziçi University, the two-credit course for juniors surveys Turkish history from the mid-19th century to the present. They emphasize social and cultural history by studying social movements, problems of urbanization, industrialization, 22 different interpretations of Kemalism, and cultural and ideological changes. They organize course topics thematically to link current issues with past legacies.77 At METU, the course has been taught as a non-credit course for sophomores and covers economic, social, political and cultural developments from 1908 to 1980. 78 Among these universities, Koç University is the only university offering this course with 3 credits and instructing it in English as part of its all English curriculum. This brings the course in an equal standing with other courses at Koç University and differentiates Koç from others. Similar to other universities trying new methods in the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course, Koç University expands the time period covered in the course from the 19th century (even earlier Ottoman and European developments) to the present. In terms of its coverage, it covers the broadest and the most current time period.79 Similar to Boğaziçi University, in addition to political and diplomatic history we emphasize social and cultural history as an attempt to understand daily lives of individuals. At Koç University, we use new approaches in teaching this course in order to fit this state-required course into our Liberal Arts program. Koç University’s mission states, “Koç University’s graduates will be leaders in their respective professions, critical thinkers and creative individuals and will be able to operate in any environment, adhere to the highest ethical standards, feel social responsibility and be committed to the values of democracy.”80 In fact, the educational philosophy of Koç University is based on the principle of “creative teaching/participatory learning.”81 The goal of Koç University is to produce humanist graduates with multiple interests. For example, an engineering student at Koç should also show interest in the arts and humanities.82 Creativity as well as analytical and critical thinking skills outlined in the university’s mission statement does not fit well with the aims of the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course, which requires rote memorization and social 23 engineering. The incorporation of some methods derived from the New History has helped us reconcile both purposes. We have been teaching this course as a part of the Liberal Arts program since 1993. In the early years, we followed the course content as suggested by YÖK, with some minor changes. The course was divided into two semesters, and the suggested coverage of the Ottoman past was extended by devoting the first semester to the history of the Ottoman Empire since the early reforms of the nineteenth century. The second semester covered the history of the Turkish Republic from the War of Independence to the death of Atatürk in 1938. We made the first major change in the 1999-200 academic year. The second semester’s coverage was extended from 1938 to contemporary events, including the transition to the multi-party era, the military coups, the Cyprus issue, and European integration. Since then the first part has been taught by a specialist in Ottoman history and the second part by a specialist in a Republican era. The current course format in terms of the Ottoman period was introduced in Fall 2003. In this format, the time period ranges from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century, with a broader introduction to the changing global context since the French Revolution. The use of virtual media and discussion sessions also started with this new format. In teaching this course, we intend to motivate students to think and ask questions on the origins and causes of historical events and to strive to create relationships between them. In the beginning, students were expected to take the course in their freshman year — a mistake, as we realised, since students need time to adapt to a system that significantly differs from secondary education. Later, the course was shifted to the sophomore year and, even later, the junior year. This made it easier for the students to read and understand the English-language material. We have used many different methods to make the course attractive. We do not require students to read a single textbook; instead, we assign different articles on the subject. 24 In this way, we want to present to them several approaches at the same time, in order to make them think, analyse and evaluate. We have organised the course both chronologically and thematically. The chronological order has proved necessary because we cover an extensive time period, from the nineteenth century to today. Although most students have studied Turkish history in secondary education, they still have difficulty remembering these dates and names because of the way in which they were asked to acquire the information. By offering a general overview of the Turkish transformation in a historical perspective, we also deal with thematic issues such as secularism, parliamentary democracy, and nationalism. Subjects including the role of the state in the economy and the role of social classes in the making of the Turkish Revolution receive attention as well. The thematically structured course provides students with the background knowledge necessary to evaluate whether the revolution happened from above or below, and to what extent a civil society has developed in Turkey. At our university, the objective of this course is not only limited to the study of the Kemalist reforms, but also includes a look at the history of Turkey, from its establishment to where we stand now. It endeavours to establish a link between today and yesterday. We intend for our students to ask themselves the following questions: What were the challenges and main questions that the Kemalist leadership faced? Why did they aim for westernization, and what kind of westernization did they want? Why did they feel a need for reforms? In order to respond to these questions, we first discuss the reforms undertaken by the Ottomans in the nineteenth century. In this way, students can see that the Kemalist reforms have a historical basis. In the YÖK-required course content, the Ottoman past is acknowledged only to show the difficulties and challenges faced by the Kemalist leadership and to demonstrate how different Kemalist reforms were from the Ottoman past. This required content assumes a 25 rupture with the Ottoman past, while we acknowledge the continuities between the Ottoman past and the Turkish Republic. The leaders of the new republic were influenced by nineteenthcentury social, political and economic developments. The longue durée of the nineteenth century — starting with the early reforms of Selim III and Mahmud II and continuing with the Tanzimat era, Abdülhamid II, and the Young Turk regime — is examined in order to introduce the general conditions of the time and to show how the ideas and actions of the Kemalist leadership came into being in relation to the broader conditions of their times. In an attempt to situate the Turkish case in an international context, the first semester of the course starts with changes in Europe after the French Revolution. Key concepts — such as nation-state, revolution, different political ideologies, secularization, and centralization — are introduced in this first part of the course. Then, a brief introduction to the pre-nineteenthcentury Ottoman administration is given in order to examine the transformations of that period. This part of the course acknowledges that the Ottoman system was not static, even before the nineteenth century. Nor does it focus on the historical details of the period, but it introduces key mechanisms of state administration, such as military organization, taxation, the ruling elites and society, religious orders, and local notables. All these mechanisms underwent important changes during the nineteenth century. In the following course segment, we teach the domestic and international developments of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. For every week of this segment, we select a theme. For example, in the week on the rule of Selim III and Mahmud II, we address the “Eastern Question,” since European involvement in the domestic affairs of the Ottoman state intensified in this era. In the final segment of the first semester, we teach about the conditions of the Ottoman state at the end of World War I, the emergence of the independence movement, and the formation of the Turkish Republic. 26 In the second semester, moving on to the Republican period, we analyse the political, social, economic and legal issues from the 1920s to the 2000s. In doing so, we situate Turkey within world history and emphasise the importance of world economic conditions and international relations. In fact, comparing the Turkish Revolution to other revolutions also demonstrates the similarities and differences with the Turkish Revolution and gives perspectives other than those based on state ideology. For example, as far as Kemalist economic policy is concerned, we try to explain that étatist policies were not specific to Turkey, but that they were also implemented by other Balkan countries in the 1930s. Additionally, we discuss what types of authentic policies the Turkish leadership endeavoured to develop. In this part, we also deal with realpolitik, while analyzing Turkey’s attitude towards World War II and regional wars such as the Gulf Wars. In this process, we take into consideration the policies of Turkey as well as those of other regional countries (such as states in the Middle East) during this period. In fact, we study Turkish policies within the general context. For example, we examine how Turkish diplomacy changed from the Cold War to the post-Cold War period and how the formation of the European Union has affected Turkey. In other words, we do not evaluate the formation of Turkish foreign policy in a unilateral way or in a bilateral relation with a specific country, but rather in a multi-dimensional way. We consider that Turkish domestic and foreign policies have always been in interaction with Western and Eastern European countries (including the Balkans and the USSR), Middle Eastern countries, and the United States. By studying the case of Turkey not in an isolated way but as an actor that influenced its environment and was influenced by it, we believe that students better comprehend the choices available to the founders of the republic and the constraints they had to face. When we use the comparative approach, we not only 27 draw comparisons between Turkey and its neighbours, but also between different periods within Turkish history. At the same time, we explore the issues of democracy and parliamentary systems in focusing on Turkey’s transition from the single-party to the multi-party system. Hence, we not only analyse the initiatives that political leaders took in Turkey, but also those of the different social classes and their reactions to state initiatives. The effects of the military coups on Turkish society are also an inevitable part of this course. Furthermore, we expose the factors leading to changing constitutions in Turkey. The contribution of other countries’ constitutions to the Turkish ones is discussed within this context. Moreover, in comparing the constitutional periods of the Ottoman Empire with those of the Republic of Turkey, we clarify both continuity and change from the Ottoman to the Republican social and political structure. This organization of the course is an attempt to introduce New History to the teaching of the course. The impact of the New History approach can be observed easily in the new course content developed at Koç University: its emphasis on comparative history and history from below, its focus on change over the longue durée and the world context, and a presentation of alternative views. The comparative approach is valuable because it locates the distinctive. What makes the Turkish revolution unique can be analysed by looking at the cases of other revolutions around the world. This argument also fits the course content proposed by YÖK and gives us space to manoeuvre within the required program. In addition to defining what is distinctive, comparative history locates the common. It allows students to ask whether or not an event is truly distinctive and helps them to construct broader global patterns. Comparative history stimulates students to use thinking skills on a higher level. Defining similarities and differences between cases improves the analytical understanding of students. Comparison leads to defining the causal factors that exist or are absent in certain events and opens a door for alternative readings of history. 83 An important component of 28 comparative history is to cultivate a geographical and cultural perspective in students’ minds. Terms like location, place, region and human-environment interaction, as well as definitions of what culture is in material and non-material terms provide such a framework.84 We have integrated several world maps that show the geopolitical location of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey interactively with other regions (such as maps showing population and trade characteristics of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey in comparison with other states). Instead of focusing on great personalities, the New History studies history from below. We have incorporated the study of Atatürk as an influential figure of the revolution, but shifted our emphasis to the analysis of different social groups in society. For example, lecture topics include women, local notables, education and mass media, in order to show the emergence of public opinion and civil society in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. These lectures are enriched with slides showing photographs of women and local customs. Statistics, population and trade figures document the religious and ethnic composition of the population. These weekly lectures shift the focus away from statesmen and international politics to groups underrepresented in history. Subjects such as women, mass media, education and population generate student interest, especially because of the use of pictorial material, as photographs about the daily lives of ordinary people and change in the patterns of social interaction show the influence of the revolution on culture and social life. Another key component of the course is the discussion sessions. Since the course is obligatory for all students, lectures have to be held in very large classrooms. This limits instructor-student interaction and decreases student interest in the course. The solution to this problem is to implement discussion sessions which are held by advanced graduate students or instructors in a group of 20 students, based on an interactive model. Every week a group of students are responsible to make presentation about readings and lectures. They also reply to the questions asked by classmates and instructors. The format of the discussion sessions is 29 very useful, since students have to work in a group, exchange opinions, stimulate discussion and present material to the classroom. The format of the presentations may be improved by using Web postings and opening a discussion group on the Internet.85 Conclusion In this paper, we have explained the reasons why at Turkish universities there has existed a state-required course on the History of the Turkish Revolution since the early years of the Republic of Turkey, as well as the evolution of this course over time. The reason why we deal with this issue is that this course is a unique case in the 20th and 21st century Europe, apart from the earlier Soviet case, which presents similarities as well as differences. Teaching this course poses the challenge of teaching a mandatory course with a number of stateimposed requirements in the context of a Liberal Arts program. But the challenge does not come only from above but also from below. There is a strong dislike and a negative reaction of the students who have been taking this course since their secondary education in a very traditional way. Even though our experience has shown positive student responses to the innovations introduced in the course, it has not been very easy to overcome the prejudices of the students who resist learning. To some extent, we were able to overcome these challenges by developing new teaching methods from New History perspective. In conclusion, we believe that students should learn about the history of their own country.86 However, this learning process should acknowledge different social actors within the country concerned. The students should also be exposed to alternative viewpoints and be aware of global changes. By introducing new teaching methods and content, the “History of 30 the Turkish Revolution” course can become an important medium to challenge traditional paradigm of history teaching in Turkey. Our efforts have been an initiative to reach this goal. 31 1 We analyze Turkey within the European context. There is no other case in Europe where the same course was taught from the elementary to the undergraduate education all along under state control. 2 Koç University is a private, nonprofit institution founded in 1993 and located in Istanbul. It is the second private university in Turkey after Bilkent and the first one in İstanbul. Koç University is founded on the principle that a substantial liberal arts education is essential for all University students. The curricula of all Colleges of the University contain required courses in mathematics, the physical and social sciences, humanities, philosophy, computing, communications, Turkish language, and history. Students have to complete these “core” courses during their freshman and sophomore years before they begin specialised courses in a chosen area of concentration. The medium of instruction at Koç University is English. For that reason, the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course is taught in English only at Koç University in Turkey. Koç University, Catalog 1996-1997, pp. 22-23. 3 Corrigan, Philip and Sayer, Derek (1985). The Great Arch: English State Formation as Cultural Revolution, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1985, p. 2 and 4. 4 Hobsbawm, Eric and Ranger, Terrence (eds) (1992). The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 5 Anderson, Benedict (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Rev. and extended ed.), London: Verso. 6 Altınay, Ayşe Gül (2004). The myth of the military-nation: militarism, gender, and education in Turkey, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 119. 7 It was called Maarif Vekâleti in the 1920s and Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı in the 1930s. 8 Altınay, 120. 9 Neumann, Christoph K. (1995). “Tarihin Yararı ve Zararı Olarak Türk Kimliği : Bir Akademik Deneme,” in Salih Özbaran (ed.): Tarih Öğretimi ve Ders Kitapları : Buca Sempozyumu ; 29 Eylül - 1 Ekim 1994, İstanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, pp. 98-106. 10 Ersanlı Behar, Büşra (1992). İktidar ve Tarih, Istanbul: Afa Yayınları, p. 202. 11 The Ottoman Empire, which participated in WWI on Germany’s side, collapsed at the end of the war in 1918. Following the signing of the Mudros Armistice in October, the Allied forces (British, French, Italian and later Greek) occupied territories under Ottoman rule including Istanbul. Beginning in 1919, various groups began fighting under the National Independence Forces on different fronts in Anatolia. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was able to establish links among local resistance groups and organise new ones. These resistance movements led by M. K. Atatürk continued until 1922, when the Turkish forces advanced into Chanak to drive the Greeks out of eastern Thrace. This period between 1919 and 1922 is known in Turkey as the War of Independence. For more detailed information see Shaw, Stanford J. (2000). From Empire to Republic, v. 1, Istanbul: Türk Tarih Kurumu. 12 For the general relationship between citizenship and education, see Weber, Eugene (1976). Peasants to Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, Stanford: Stanford University Press. Altınay, 119. Ahmad, Feroz (2003). The Quest for Identity, Oxford: One World, p. 87. 15 Tarih IV, Kemalist Eğitim Tarih Dersleri (1931-1941) (2001), Istanbul: Kaynak Yayınları, 262. 13 14 32 Ibid., III. Afet İnan was one of the foremost Turkish scholars of the time and an adopted daughter of Atatürk. 17 Ersanlı Behar, 159. 18 On the eve of the world economic crisis, the economic implications of the Lausanne Treaty (1923) had already come to an end by 1928. The treaty required Turkey to pay two-third of the Ottoman Debt. Moreover, it prevented Turkey to develop a new customs policy and imposed that the fetters of capitulations continue for an additional five year. The capitulations were special extraterritorial privileges given to subjects of foreign powers in judicial and commercial-economic fields by the Ottomans. For more detailed information see İnalcık, Halil (1971). “İmtiyaz”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 3, 1179-89. 19 Barlas, Dilek. (1998) Etatism and Diplomacy in Turkey, Leiden: Brill, pp. 105-106. 20 Tarih IV, Kemalist Eğitim Tarih Dersleri (1931-1941), p. IV. 21 Kaplan, İsmail (1999). Türkiye’de Milli Eğitim İdeolojisi, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, p. 181. 22 Between 1930 and 1933, İsmet İnönü was Prime Minister, Prof. Y. Hikmet Bayur the Minister of Education, and Prof. Y. Kemal Tengirşenk the Minister of Economy, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and the Minister of Justice. Between 1931-1937, Recep Peker was the general secretary of the Republican People’s Party (Cumhurriyet Halk Partisi, CHP), the party in power. M. Esat Bozkurt was Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister of Justice in the 1920s. İlk İnkilap Tarihi Ders Notları (1997), İstanbul: Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Vakfı, pp. 11-15. 23 Bayur, Yusuf Hikmet (1991). Türk İnkilabı Tarihi, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, XII. 24 Ibid., XIII. 25 İlk İnkilap Tarihi Ders Notları, 99-101. 26 İbid., 71-74. 27 İnkilap Kürsüsünde İsmet Paşanın Dersi. (April 1934) Ülkü, 3 (14), 81-87. 28 Ibid., 85. 29 Ibid., 86. 30 Gülalp, Haldun and Barlas, Dilek. (1998). “Bilginin Evrenselliği, Farklılığın Sorunsallığı”, in Semih Dikmen, Tanıl Bora and Kaya Şahin (Eds.), Sosyal Bilimleri Yeniden Düşünmek (pp. 281-86). İstanbul: Metis Yayınları. As a result of these efforts, the six arrows (republican, nationalist, étatist, populist, revolutionary, and secular) of the CHP were incorporated into the constitution in 1937. The General Secretary of the CHP especially emphasised in his lectures that nobody in Turkey would be in favor of socialism and liberalism, which contradicted étatism. “1932 Senesi Bütçesi Hakkında Yeniden Tanzim Kılınan 1/317 Numaralı Kanun Layihası ve Bütçe Encümeni Mazbatası,” T.B.M.M. Zabıt Ceridesi. (21. VI. 1932), 9, 211212. 31 Tengirşenk, Yusuf Kemal. Ankara İnkilap Kürsüsünde, Hakimiyeti Milliye, 8 April 1934. 32 Tengirşenk, Yusuf Kemal. Ankara İnkilap Kürsüsünde, Hakimiyeti Milliye, 10 May 1934. He also discussed other economic revolutions such as the Agricultural and Transportation Revolution (mainly railroads). Tengirşenk, Yusuf Kemal. Türk İnkilabı Dersleri, Ekonomik Değişmeler (1935). İstanbul: Resimli Ay Basımevi, pp. 37-58. 33 Peker, Recep. İnkilap Dersleri (1936). Ankara: Ulus Basımevi, pp. 15-27. 34 Dorotich, Daniel. (Fall 1967). “A Turning Point in the Soviet School: The Seventeenth Party Congress and the Teaching of History”, History of Education Quarterly, 7 (3), 297. 35 Ibid. 16 33 Bradenberger, D. L. and Dubrovsky, A. M. (July 1998). “The People Need a Tsar: The Emergence of National Bolshevism as Stalinist Ideology, 1931-1941”, Europe-Asia Studies, 50 (5), 874. 37 Laugla, Jon. (1988). “Soviet Education Policy 1917-1935: From Ideology to Bureaucratic Control”, Oxford Review of Education, 14 (3), 295. 38 Bradenberger and Dubrovsky, 875. 39 Hoffmann, David L. (2004). “Was There a “Great Retreat” from Soviet Socialism?” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 5 (4), 666. 40 http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1934/x01/x01.htm 41 Hoffman, 666. 42 http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1939/x01/index.htm 43 İnan, Süleyman. (July 2007). “The First “History of the Turkish Revolution” Lectures and Courses in Turkish Universities (1934-42)”, Middle Eastern Studies 43 (4), 605. 44 İnan, 605. 45 Aslan, Erdal (1995). “Devrim Tarihi Ders Kitapları”, in S. Özbaran (Eds.), Tarih Öğretimi ve Ders Kitapları, Buca Sempozyumu. Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, pp. 295-313. 46 The leading intellectuals of the time, namely, Behice Boran, Niyazi Berkes, Sabiha Sertel and Zekeriya Sertel, published leftist newspapers and periodicals (Tan and Yurt ve Dünya) during WWII. But they were forced to close them down towards the end of the war. 47 Özüçetin, Yaşar, and Nadar, Senem (2010). “Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâb Tarihi Dersinin Üniversiteler Düzeyinde Okutulmaya Başlanması ve Gelinen Süreç”, The Journal of International Social Research, 3(11), 474. 48 Akbaba, Bülent (2009). “Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi Dersinin Öğretimine Yönelik Bir Durum Değerlendirmesi (Gazi Üniversitesi Örneği)”, Türkiye Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 13(1), 32. 49 Karal, Enver Ziya (1971). Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Tarihi (1918-1965), Istanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi. 50 Özüçetin and Nadar, 474. 51 Although YÖK regulations have changed many times, the basic structure and function of the council have remained the same since its foundation. YÖK regulates university organizations and has authority concerning structural and curricular initiations and changes in universities. Public and private universities, institutes, two-year vocational schools, and threeyear educational institutes are all dependent on YÖK. See Mızıkacı Fatma (2003). “Quality Systems and Accreditation in Higher Education: An Overview of Turkish Higher Education”, Quality in Higher Education, 9 (1), 96. 52 These institutes were established at Hacettepe, Ankara, Dokuz Eylül, Boğaziçi, Istanbul and Atatürk Universities. See Yılmaz, Mustafa (2000). “Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Dersleri ve Bu Konuda Yapılan Araştırmalar”, Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi, 46 (XVI), 313-326. 53 Translated by the authors. Doğaner, Yasemin (2005). Yüksek Öğretimde Atatürk İlke ve İnkılaplarının Öğretimi ile İlgili Düşünceler, p. 2. See http://www.ait.hacettepe.edu.tr/akademik/arsiv/yuksek_ogretim.pdf 54 The faculty teaching the History of Turkish Revolution course at Koç University was interviewed by YÖK representatives in Fall 2007. 55 Kürkçüoğlu, Ömer et al. (1989). Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi, Ankara:Yüksek Öğrenim Kurulu Yayınları. 56 Akbaba 2009, 32. 57 The Turkish Revolution is taught as a subject in Social Sciences courses starting in the fifth grade. The History of the Turkish Revolution is taught as a separate course for the first time in 36 34 the eighth grade; that is the last year of elementary school. Students continue to take courses on the Turkish Revolution in high schools, including grades nine to twelve. 58 Koullapis, Lory-Grcgory (1995). “Türkiye'de Tarih Ders Kitaplan ve UNESCO'nun Önerileri”, in Salih Özbaran (ed.): Tarih Öğretimi ve Ders Kitapları : Buca Sempozyumu ; 29 Eylül - 1 Ekim 1994. İstanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, pp: 273-282. 59 Tekeli, İlhan (1995). “Küreselleşen Dünyada Tarih Öğretiminin Amaçlan Ne Olabilir?” in Salih Özbaran (ed.): Tarih Öğretimi ve Ders Kitapları : Buca Sempozyumu ; 29 Eylül - 1 Ekim 1994. İstanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, pp: 34-42. 60 Özbaran, Salih (1992). Tarih ve Öğretimi, Istanbul: Cem Yayınevi, 184- 218. 61 From Murat Hatipoğlu’s speech at Hacettepe University meeting on the “History of the Turkish Revolution” course. Translated by the authors. See Yediyıldız, Bahaeddin, Ertan, T. Faik, and Üstün, Kutay (2004). Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi’nde Yöntem Arayışları, Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi Yayınları, p.22. 62 For Şevket Pamuk’s speech, see Yediyıldız, Bahaeddin, Ertan, T. Faik, and Üstün, Kutay 2004, 28. 63 Yediyıldız, Bahaeddin, Ertan, T. Faik, and Üstün, Kutay 2004, 79-85. Similar meetings were organised at İstanbul Technical University in 1997 and Boğaziçi University in 1999. For proceedings of the Istanbul Technical University meeting, see Tanör, Bülent, Toprak, Zafer and Berktay, Halil (Eds.) (1997). “İnkilap Tarihi” Dersleri Nasıl Okutulmalı, Istanbul: Sarmal Yayınevi. 64 Akbaba , 44-50; Doğaner, 6-14. 65 Universities which are experiencing with new curricula will be discussed in the below section. 66 Mumcu, Ahmet (1998). Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi, Eskişehir: AÖF Yayınları. 67 Karal 1971. 68 In the recent years, alternative approaches have emerged such as post-modern readings. In this paper, we only discuss general theory and methods that we use in the History of Turkish Revolution course. 69 A good example of traditional approach in history is Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, London: Strahan & Cadell. For an earlier critique of the traditional approach, see Oppenheimer, Franz (1927). History and Sociology. In W.F. Ogburn & A. Goldenweiser (Eds.), The Social Sciences and Their interrelations, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, pp. 221-234. 70 For a definition and critique, see Burke, Peter (1992). Overture: The New History, its Past and its Future. In New Perspectives on Historical Writing, P. Burke (Eds.), University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 3-23. 71 Interestingly, the impact of Bloch and Febvre’s work was visible on the famous four volumes of Tarih, Kemalist Eğitim Tarih Dersleri (1931-1941). 72 Braudel, Fernand (1995). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, v. 1, Los Angeles: University of California Press. 73 Burke, 3-23. 74 Özbaran, Salih (1998). “Türkiye’de Tarih Eğitimi ve Ders Kitapları Üstüne Düşünceler”, in Tarih Eğitimi ve Tarihteki Öteki Sorunu, 2. Uluslararası Tarih Kongresi. Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, pp: 61-70. 75 See the online catalogue of Bilkent University. http://catalog.bilkent.edu.tr/current/course/c94202.html 76 See Sabancı University course offerings. http://www.sabanciuniv.edu/syllabus/courses.cfm?term=01&year=2005&subject=HIST&cod e=191&lan=eng 35 77 See the web page of Atatürk Institute for Modern Turkish History. http://www.boun.edu.tr/undergraduate/institutes/ataturk_institute.html Also, personal communication with Nadir Özbek, 24 July 2010. 78 See METU Academic Catalogue. https://catalog.metu.edu.tr/course.php?course_code=2402206. 79 Zafer Toprak, in Üniversitelerde Atatürk İlkeleri ve Devrim Tarihi Dersleri (A seminar organized by METU Faculty Association –ODTÜ Öğretim Üyeleri Derneği, 11 May 2001), pp. 10-11. http://www.oed.org.tr/oed/index2.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=12&Itemi d=13 80 Emphasis added. See http://www.ku.edu.tr/ku/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2189&Itemid=1016 81 Koç University, Catalogue 2000-2001, p. 28. 82 Geleceğe Açılan Bilim Kapısı, Koç Üniversitesi Kuruluş Tarihi (2002). İstanbul: Vehbi Koç Vakfı, p. 175. 83 Bain, Robert B. (1997). “Building an Essential World History Tool: Teaching Comparative History”, in Heidi Roupp (Eds.), Teaching World History, 29-33, and Winks, Robert W. (1968). Comparative Studies and History. The History Teacher, 1 (4), 39-43. 84 Andrian, Bob (1997) “World History: Not Why? But What? And How?”, in Heidi Roupp (Eds.) Teaching World History, 20-28. 85 For an effective example of Web discussion boards in teaching history, see Zarate, Eloy (1998). “Cyberspace, Scholarship, and Survey Courses: A Prototype for Teaching World History”, The History Teacher 32 (1), 57-65. 86 But, the course must not be required by the state. 36