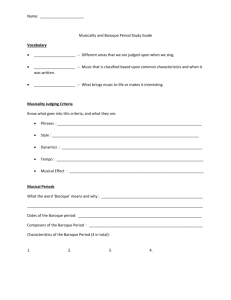

Music of the Early Baroque Period

advertisement

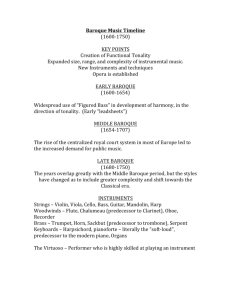

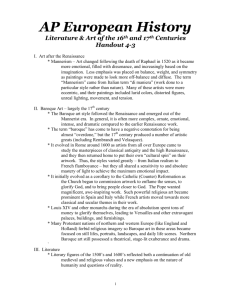

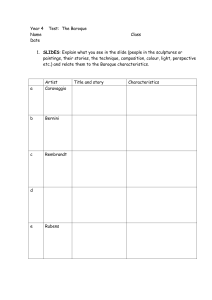

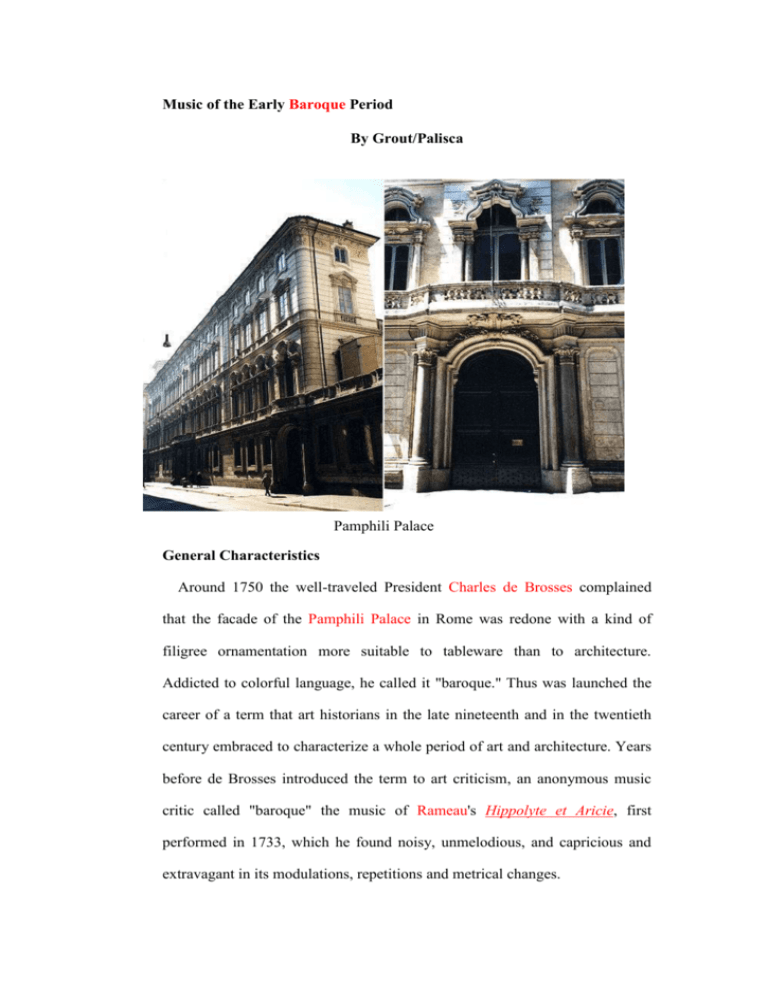

Music of the Early Baroque Period By Grout/Palisca Pamphili Palace General Characteristics Around 1750 the well-traveled President Charles de Brosses complained that the facade of the Pamphili Palace in Rome was redone with a kind of filigree ornamentation more suitable to tableware than to architecture. Addicted to colorful language, he called it "baroque." Thus was launched the career of a term that art historians in the late nineteenth and in the twentieth century embraced to characterize a whole period of art and architecture. Years before de Brosses introduced the term to art criticism, an anonymous music critic called "baroque" the music of Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie, first performed in 1733, which he found noisy, unmelodious, and capricious and extravagant in its modulations, repetitions and metrical changes. If the word baroque was used in the music criticism of the eighteenth century in a somewhat derogatory way, through the art criticism of Jacob Burckhardt and Karl Baedeker in the nineteenth century it acquired a more favorable general meaning that described the flamboyant, decorative, and expressionistic tendencies of seventeenth-century painting and architecture. From art criticism the term was imported back to music history in the 1920s. Now it was applied to the period that paralleled roughly what art historians called "baroque," namely from the late sixteenth century until around 1750. The term was used, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, also for the style of music that was thought to be typical of that period. But this usage is less defensible than its application as a period designation, because the period contained too great a diversity of styles to be embraced by one term. Therefore in the present edition of this book the term Baroque; will rarely be employed as a style designation. But because it does evoke the artistic and literary culture of an entire era, the term is useful as a period designation. As with other epochs, the boundary dates are only approximations, since many characteristics of the period were in evidence before 1600 and many were declining by the 1730s. But it is possible and convenient to take these dates as rough limits within which certain ways of organizing musical material, certain ideals of musical sound, and certain kinds of musical expression developed from diverse and scattered beginnings to a method of composition that consistently accepted certain conventions. What are these characteristics? To answer this question, we must consider how music at this time is related to the surroundings that produced it. The use of the term baroque to circumscribe the music of 1600-1750 suggests that historians believe the qualities of this music arc in some ways similar to those of contemporary architecture, painting, literature, and perhaps also science and philosophy. We are tempted to believe that a connection exists, not only in the seventeenth century, but in all eras, between music and the other creative activities of man: that the music produced in any age must reflect, in terms appropriate to its own nature, the same conceptions and tendencies that arc expressed in other arts contemporary with it. For this reason general labels like Baroque, Gothic, and Romantic are often used in music history instead of designations that might more precisely describe purely musical characteristics. It is true that these general words are liable to be misunderstood. Thus baroque, which comes from a Portuguese word describing a pearl of irregular shape, was long used in the pejorative sense of abnormal, bizarre, exaggerated, in bad taste, grotesque; the word is still defined thus in the dictionaries and still carries at least some of that meaning for many people. However, the music written between 1600 and 1750 is not on the whole any more abnormal, fantastic, or grotesque than that of any other period. GEOGRAPHICAL AND CULTURAL BACKGROUND Italian attitudes dominated the musical thinking of this period. From the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries, Italy remained the most influential musical nation of Europe. One should say region rather than nation, for the Italian peninsula was split into areas ruled by Spain and Austria, the Papal States, and a half-dozen smaller independent states which allied themselves from time to time with larger European powers and in general heartily distrusted one another. Yet political sickness apparently does not preclude artistic health: Venice was a leading musical city all through the seventeenth century despite its political impotence, and the same was true of Naples during most of the eighteenth century. Rome exerted a steady influence on sacred music and for a time in the seventeenth century was an important center of opera and cantata; Florence had a brilliant period near the beginning of the seventeenth century. To turn to the other European countries during the Baroque era, France in the 1630s began to develop a national style of music which resisted Italian influences for over a hundred years. In Germany an already weakened musical culture was overwhelmed by the calamity of the Thirty Years' War (1618-48), but despite political disunity there was a mighty resurgence in the following generations, most notably in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. In England the glories of the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages faded with the period of the Civil War and the Commonwealth (1642-60); a brief, brilliant revival toward the end of the century was followed by nearly complete capitulation to Italian style. The musical primacy of Italy during the Baroque period was not absolute, but even in the countries that developed and maintained their own distinctive national idiom the Italian influence could not be escaped. It was prominent in France through the first half of the seventeenth century especially; the composer whose works did most to establish the national French style after 1660, Jean-Baptiste Lully, was an Italian by birth. In Germany in the latter part of the century, Italian style was the principal foundation on which German composers built; the art of Bach owed much to Italy, and Handel's work was as much Italian as German. By the end of the Baroque period, in fact, the music of Europe had become an international language with Italian roots.