Matty Ma - Saving the Southeast Asian Rainforests

advertisement

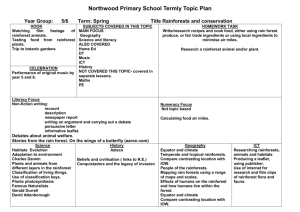

1 Matty Ma Biology Jan. 14, 2012 Saving the Southeast Asian Rainforests Southeast Asia is an area widely renowned for its unique cultures and traditions. However, the region is much less recognized for what is perhaps the greatest resource it possesses — its rainforests. Recently, severe deforestation in these forests, caused primarily by extensive logging, has called for public awareness and attention. The loss of rainforests poses a great threat to the plants and animals that live in these forests, as well as indigenous people who depend on the forests for survival. Yet as a result of economic benefits gained by exploiting the rainforests, local governments and many people worldwide are generally permissive toward commercial activities that damage the forests. Therefore, efforts to protect and restore these forests are faced with various kinds of obstacles and practical problems. At the moment, logging still continues at an alarming pace. If this issue is not fully comprehended, and if effective measures are not taken to protect the rainforests, larger areas of the forests will be lost, and more serious consequences will arise. Thus, an understanding of the present situation becomes critically important. This understanding should begin with knowledge of background information about these rainforests. Rainforests in Southeast Asia are located in the regions between India and Burma, as well as between Java and Borneo (see Fig. 1). Most of the rainforests exist in Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Java, Sumatra and Borneo, while India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka also have small areas of rainforest. The forests cover an area of 1,112,000 square miles, over 15% 2 of the Earth’s total rainforest area. Biodiversity is an important characteristic of the Southeast Asian rainforests. The most famous animals that inhabit these rainforests are tigers and orangutans, which cannot be found on other continents. Some other native animals are palm civets, dawn bats, Jambu fruit doves, king cobras, Wagler’s pit vipers, and Asian elephants. The rainforests have especially diverse primate species, including proboscis monkeys, douc langurs, silvery gibbons, and slender lorises. Many of the species that inhabit these rainforests are critically endangered. The Sumatran rhinoceros, for instance, has a population of only about 300-500. In addition, the Malayan tapir, less than 50 of which are still alive in the wild, is another example of a native endangered species. These rainforests are also home to myriads of plant species. Some examples are Bengal bamboo, durians, Jambu, Kapok trees, mangroves, strangler figs, and tualang trees. Perhaps the most unique type of plant in these forests is the Rafflesia, which can only be found in certain areas of Southeast Asia. It is famous for its great size and the unpleasant odor it emits, which attracts beetles and flies into the flower to pollinate it. Sadly, the Rafflesia is becoming increasingly endangered because, like numerous other species, it is losing its habitat as the rainforests are being destroyed. With the necessary background knowledge, we can begin to understand the consequences of logging and deforestation. First, an idea of the rate at which the rainforests are disappearing is required. According to reports from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the annual forest loss in Southeast Asia from 1980 to 1990 was 3.9 million hectares, or about 1.2% per year. As a result of the decreased total forest area and the 3 raised awareness of governments and individuals, the annual area of deforestation went down to 2.5 million hectares from 1990 to 2000. However, from 2000 to 2005, rising commercial needs caused the deforestation rate to increase to 2.8 million hectares per year (see Fig. 2). At present, more than 85% of the original rainforest in Southeast Asia has been destroyed, and the percentage is increasing year by year. At the deforestation rate maintained in recent years, most of the rainforest will be gone in the next 20 years or so. Among the various causes of rainforest deforestation, commercial logging is the single most important. This is largely because in order to remove only a few logs, a large area of forest is destroyed. The heavy machinery used in logging causes disturbance to the soil, which makes regeneration of the forest much more difficult. In addition, logging creates roads in the forest, making them accessible to landless farmers, who will often clear the forest to use as land for agriculture. Deforestation and logging have a grave impact on the ecology of the rainforest, especially due to the fact that they threaten the key species that dwell in those forests. Many mutualistic relationships exist between different plant and animal species in the ecosystem of the rainforest. The very existence of some of these species has a great effect on the health and survival of other species, as well as the balance of the entire ecological system. These species are known as keystone species. In the Southeast Asian rainforests, many keystone species are either already endangered, or on their way to becoming endangered. Should any of these species one day disappear entirely, additional losses will be triggered, and the extinction of many other species will be inevitable. It is impossible to list all of the keystone species in the rainforest, due to the tremendous 4 total number of species and the intricacy of relationships between these species. However, a few typical examples can be provided. Orangutans play a key role in dispersing seeds and preserving the diversity of rainforest plants. Studies have shown that in areas of the rainforest where the orangutan population has drastically decreased, plant biodiversity has already been affected. When searching for vegetation, the Asian elephant will often knock down trees and tear off branches. This behavior creates natural openings in the forest canopy, allowing sunlight to reach plants growing on the forest floor. At the same time, vegetation is brought down from the canopy, providing food for antelopes, forest buffaloes, forest hogs, etc. The kapok tree, another example of a keystone species, offers a habitat for epiphytes in its branches. This allows animals to move around the rainforest without touching the forest floor. For monkeys, this function of kapok trees is absolutely essential for survival, as monkeys not hidden in tree tops become easy prey for eagles. The loss of rainforests also negatively affects indigenous peoples who live in and rely on these forests. In Southeast Asia, immigration waves and deforestation due to logging have been pushing the native peoples of the rainforest off their lands, and into steadily decreasing areas. Today, they can only be found in remote forest areas in Borneo, New Guinea, the Philippines and the Malay. As a result, their traditions are being lost, and their methods of cultivating the forest and using its resources without harming it are being replaced by the wanton exploitation of logging companies. At this point, one might ask: if the problem is such a serious one, why aren’t there more conservation efforts? Part of the answer to this very pertinent question lies in the fact that logging is extremely beneficial to Southeast Asian economies. In recent history, Indonesia 5 and Malaysia, both of which are among the major timber exporters in Southeast Asia, have experienced economic boons due to deforestation. In the 1960s and 1970s, Indonesia overcame a severe economic crisis largely through selling timber to foreign countries. Malaysia, on the other hand, began its quick development by replacing forests with rubber and oil palm plantations. Today, even though many Southeast Asian countries are relying more and more on their high-tech industries for economic development, logging still occupies an important role in these countries. For instance, Malaysia and Indonesia together produce 85% of the world’s palm oil, which is the main cause of logging. Thus, despite technological advances and the rise of other industries, the timber industries of these countries continue to thrive. On the other hand, profits obtained from logging are not limited to Southeast Asia. Many countries worldwide import timber from Southeast Asia for various purposes. Some beautiful and valuable types of wood, such as mahogany, kapok and teak, are purchased by developed countries, and used to construct furniture, doors, flooring, plywood and other types of woodware. These manufactured goods are then sold for many times the price of the raw timber used to make them. Smaller trees that are not suitable for construction are often used as charcoal. Mangrove forests, for instance, have become one of the most endangered habitats in the world, due to extensive logging driven by local and global demands for fuelwood. In some Asian countries such as Japan and China, wood obtained from logging the rainforests is also used to make disposable chopsticks. In these two countries alone, over 140 million pairs are thrown away each day. Thus, because of the various profits of exploiting the resources of the rainforests, Southeast Asian governments and many beneficiaries worldwide are generally 6 tolerant toward logging, and are not strongly determined to protect the rainforests at the expense of their own economic gains. In many cases, the Southeast Asian governments’ permissive standpoint greatly hinders rainforest conservation. Deforestation in national parks serves as a typical example. Many Southeast Asian countries have large areas of national parks and protected forest. In fact, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), forests in 9% of Kalimantan, 8% of Sarawak and 14% of Sabah have some kind of protection. Hidden behind these impressive statistics, however, is the fact that logging is quite common in many of the protected areas. Governments have often granted logging concessions within these areas to logging companies, in order to support the profitable timber industry. These concessions have a disastrous effect on forest preservation. In the case of Kutai National Park in Indonesia, for instance, timber concessions have reduced its area from its original 306,000 hectares in 1936 to its present approximately 200,000 hectares. The position of the governments on rainforest preservation is also manifested by many of their judicial decisions. In recent years, the Sarawak tribes of Malaysia have been involved in multiple conflicts with logging companies for not allowing loggers to set foot in their ancestral lands. The Malaysian government’s position concerning this issue is that the Sarawak have no rights to the forest, which is open to commercial logging. On September 9th of this year, a case between Sarawak tribes and the Malaysian state government was brought before the Malaysian federal court. The state government had seized indigenous forest lands to build a hydroelectric power plant, but the Sarawak tribes refused to give up their claims to those lands, resulting in a legal battle that had already lasted for twelve years. In the 7 meantime, the government continued to work on the construction of the power plant, which has displaced 10,000 natives and flooded 700 square kilometers of untouched rainforest. In the end, the federal court ruled in favor of the state government, and construction of the power plant was allowed to continue. The Sarawak lost yet another major battle in the fight for their native lands, as well as for the rainforest. However, not all failed attempts at protecting the rainforests can be attributed to government attitudes and decisions. In some cases, practical obstacles are what impede conservation. For instance, although local governments are very active in battling against illegal logging, they face multiple realistic challenges. In Indonesia, for example, 2000 park rangers with very limited access to ground vehicles, boats or helicopters patrol an area of more than 10 million hectares in 35 national parks. Apparently, these rangers can only provide, at best, inadequate protection for the forests in these national parks. In order to effectively protect the forests from illegal logging, cooperation of the international community is required. Restoring the rainforests is another problem of practicality. It would be both impossible and unwise to restore the forests to the full area that they occupied before the onset of deforestation. Much of the land that has been cleared is now taken up by pastures, plantations and farms that sustain the lives of local people. Therefore, it would be a much better idea to optimize the utilization of these lands, than to restore them back to forest land. In regions where some of the original forest still remains, and where there is little human activity, restoration of the forest is possible. However, the rate of recovery is extremely slow. Although deforested land can be restored to degraded forest land in as little as 3- 4 years, the 8 time required for the forest to fully regenerate, and become indistinct from the original forest, can be up to 4 thousand years, according to some estimates. At this point, saving the Southeast Asian rainforests is a difficult yet absolutely necessary task. The serious consequences of deforestation are already evident, and will likely in time become devastating if effective conservation methods are not implemented. Yet economic gains are affecting the attitudes of people worldwide toward rainforest protection, and practical obstacles further lower the chance of success for environmental actions. However, on the other hand, people are becoming increasingly aware of the problem, and newer, more effectual measures are being taken. Ecotourism is raising consciousness toward rainforest conservation, and ongoing scientific research is revealing ways to minimize environmental damage caused by economic development. Even though there is still a long way to go, the future of rainforest protection in Southeast Asia is starting to look hopeful. 9 Fig. 1: Location of the Southeast Asian Rainforests Rainforests in Southeast Asia are located in the regions between India and Burma, as well as between Java and Borneo. Fig. 2: Tropical Deforestation by Region, 1990-2000 & 2000-2005 In thousand hectares per year. Source: http://rainforests.mongabay.com The annual forest loss in the Southeast Asia area from 1990 to 2000 was 2.5 million hectares. From 2000 to 2005, the deforestation rate increased to 2.8 million hectares per year. 10 Bibliography "Asian Peoples of the Rainforest." Mongabay. Web. 14 Nov. 2011. <http://rainforests.mongabay.com>. "Asian Rainforest." Rainforest Facts. Web. 24 Oct. 2011. <http://www.rainforest-facts.com>. "Average Annual Deforestation Rates in hectares, 2000-2005." Mongabay. Web. 1 Nov. 2011. <http://www.mongabay.com>. "Borneo." Mongabay. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. <http://www.mongabay.com>. "The Causes of Rainforest Destruction." The Rainforest Information Centre. Web. 1 Nov. 2011. <http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au>. "Deforestation in Malaysia." Wikipedia. Web. 3 Dec. 2011. <http://www.wikipedia.org>. "Deforestation in Tropical Asia." Mongabay. Web. 1 Nov. 2011. <http://www.mongabay.com>. "Environmental and Cultural Implications of Rainforest Deforestation in Southeast Asia." Angelfire. Web. 14 Nov. 2011. <http://www.angelfire.com>. "A Forest Falls in Cambodia." Asia Times Online. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. <http://www.atimes.com>. 11 "Hope for the Rain Forests." Liza’s Reef. Web. 1 Nov. 2011. <http://www.lizasreef.com>. "How Long Does It Take for a Rainforest to Regenerate?" NewScientist. Web. 10 Jan. 2011. <http://www.newscientist.com>. "How to Save Tropical Rainforests." Mongabay. Web. 10 Jan. 2011. <http://rainforests.mongabay.com>. "Human Threats to Rainforests- Fuelwood, Roads, Climate." Mongabay. Web. 31 Dec. 2011. <http://rainforests.mongabay.com>. "Information on Rainforests in Southeast Asia." eHow. Web. 17 Oct. 2011. <http://www.ehow.com>. "Malaysian Court Blocks Rainforest Tribes’ Fight against Mega-dam in Borneo." Mongabay. Web. 14 Nov. 2011. <http://news.mongabay.com>. Nuwer, Rachel. "Disposable Chopsticks Strip Asian Forests." The New York Times. 24 Oct. 2011. Print. "The Orangutan under Threat." Greenpeace. Web. 6 Nov. 2011. <http://www.greenpeace.org>. "Rafflesia." ThinkQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011. <http://library.thinkquest.org>. "Rainforests of the World." Rainforest Info. Web. 17 Oct. 2011. <http://www.rainforestinfo.org>. "SE Asian Rainforests Disappearing Fast." People & the Planet. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. 12 <http://www.peopleandplanet.net>. "Southeast Asian Rainforest Animals." Blue Planet Biomes. Web. 24 Oct. 2011. <http://www.blueplanetbiomes.org>. "Southeast Asia Rainforest Facts." eHow. Web. 1 Nov. 2011. <http://www.eHow.com>. "Southeast Asia Rainforest Map." Jungle Photos. Web. 17 Oct. 2011. <http://junglephotos.com>. "Southeast Asian Rainforests." Blue Planet Biomes. Web. 17 Oct. 2011. <http://www.blueplanetbiomes.org>. Stevens, William K. "Huge Conservation Effort Aims to Save Vanishing Architect of the Savannah." The New York Times. 28 Feb. 1989. Print. "Tropical Rainforests." Freewebs. Web. 6 Nov. 2011. <http://www.freewebs.com>. "Uses of the Rainforest." ThinkQuest. Web. 31 Dec. 2011. <http://library.thinkquest.org>. "The Vanishing Rainforests." HubPages. Web. 31 Dec. 2011. <http://nandalala.hubpages.com>. "Why are They Being Destroyed?" Rainforest Concern. Web. 31 Dec. 2011. <http://www.rainforestconcern.org>.