Agency - The Feudal Times

Agency

Summer 1999

Professor Tierney

Phone (419) 530-2879

Office Suite 2008A e-mail: jtierne@pop3.utoledo.edu

May 24, 1999 Class Agency law is concerned with any "principal"-"agent" relationship -- that is a relationship in which one person has legal authority to act for another. Such relationships arise from explicit appointment, or by implication.

The relationships generally associated with agency law include guardian-ward, executor or administrator-decedent, and employer-employee.

The law of agency is based on the Latin maxim " Qui facit per alium, facit per se ," which means " he who acts through another is deemed in law to do it himself ."

Agency, in its legal sense, nearly always relates to commercial or contractual dealings.

I. Introduction to the Law of Unincorporated Business Enterprises

1) Corporation (p. 1) a) Ownership : (Financial power and elect Board of Directors) b) Management : Centralized and are elected and directed by the

Board of Directors. (Separation of Ownership and Management) c) Liability : is limited to the assets of the Corporation. (Worst that could happen is lose the investment) d) Free Transferability of Interest : Usually corporate shares can be traded freely (w/o and OK from the other shareholders). Transferee steps into the shoes of the transferor. e) Continuity of Life : Even if shareholders die the Corp. goes on in perpetuity. (If another party enters into a K w/ Corp. there is no problem) f) Tax Issues : This is the problem because of double taxation.

Corporation (retained earnings) and shareholders (dividends) are both taxed. Ways around double taxation is by forming a S corporation (but there are some restrictions).

2) Different Forms of Unincorporated Businesses (p. 4) a) Sole Proprietorship (p. 4) Default form of Business. Business and personal affairs are treated as one.

(1) Management : You are the management

(2) Liability : Personally liable

(3) Free Transferability of interest : Nothing to transfer.

(4) Continuity of Life : If you die the business dies.

(5) Tax Issues : Taxed personally on income b) Business Trust (p. 5)

(1) Management :

(2) Liability :

(3) Free Transferability of interest :

(4) Continuity of Life :

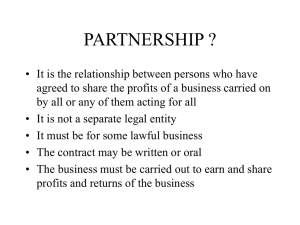

(5) Tax Issues : c) (General) Partnership (p. 6) Default form of Business. Uniform

Partnership Act 1914 (Ohio) (UPA)/ Revised Uniform Partnership

Act 1994 (RUPA)

(1) Management : Partners have the rights to manage the business, unless they otherwise agree.

(2) Liability : Personally liable for debts of the firm. (This could be contracted around via insurance arrangements)

(3) Free Transferability of interest : UPA says there is no transferability of interest without consent of all other partners.

(This can be altered via contract)

(4) Continuity of Life : Under UPA owner level changes can create problems and cause dissolution if a partner dies.

(5) Tax Issues : Income is taxed only once. Partnership is not a taxable entity. Pass through treatment of all income. d) Limited Liability Partnership (LLP ) (p. 7) Throws into the partnership statutes that the Limited Partnership can remain a UPA partnership and exclude joint and severable liability of the organization.

(1) Management : Same as a Limited Partnership

(2) Liability : THIS IS THE DIFFERENCE.

(3) Free Transferability of interest : Same as a limited partnership.

(4) Continuity of Life : Same as a limited partnership.

(5) Tax Issues : Same as a limited partnership. e) Limited Partnership (p. 7) Uniform Limited Partnership Act 1917

ULPA/ Revised in 1976 and 1985

(1) Management : There are two classes of partners, general and limited partners. General partners are the managers and limited have no power.

(2) Liability : Limited partners have limited liability to their investments and any other amounts they agree to. General partner has the same liability as in a General partnership.

(3) Free Transferability of interest : Exit privileges are still difficult.

(4) Continuity of Life : General partner dies could end partnership, limited partner dies

—no problem.

(5) Tax Issues : Limited partnership was a prime vehicle for tax shelters. Flow through of income and pass through of losses. f) Limited Liability Limited Partnership (LLLP) (p. 8)

(1) Management : Same as the partnership

(2) Liability : Limited liability is extended to the General Partners

(3) Free Transferability of interest : Same as the partnership

(4) Continuity of Life : Same as the partnership

(5) Tax Issues : Same as the partnership. g) Limited Liability Company (LLC) (p. 8)

(1) Management : is shared among the owners, just as it is among partners in a partnership, in a member managed LLC. Owners

are free to form a manager managed LLC, placing management in the hands of managers.

(2) Liability : of owners is limited in the sense that owners (called members) are not liable as such for the debts of the business, and in that sense are in a similar position to shareholders of a corporation.

(3) Free Transferability of interest : Decide if you want to have FTI or not.

(4) Continuity of Life : Decide if a member dies whether they will dissolve or not.

(5) Tax Issues : Initially they were treated as a partnership on a pass-through basis (if it had only 3 of the 4 attributes of a corporation). If not then taxed as a corporation.

Check-the-

Box Regulation, Treas. Reg. §301.7701

: provides that an unincorporated business is taxed as a partnership unless it elects to be taxed as a corporation. Reg. replaces the Kinter regulations which said that any entity having a majority of 4 corporate characteristics of (1) limited liability, (2) continuity of life, (3) free transferability of interests, and (4) centralized management was taxed as a corporation.

May 26, 1999 Class

II. The Agency Relationship; The Ambiguous Principal Problem; Subagency (p. 11):

1) The Agency Relationship (p. 12):

Principal

Agent

Rights and duties flow between the Principal and Agent .

Agent creates legal rights and duties between 3 rd parties and

The principal.

3 rd parties

Equal dignities rule : If I am appointing an agent to create a contract which needs to be in writing in order to avoid the statute of frauds, the relationship between the agent and the principal also must be in writing.

Carrier v. McLlarky (p. 12): This case is where a contractor told his customer that he would try to get a refund for her. An agency relationship is created when a principal gives authority to act on his or her behalf and the agent consents to do so. The creation of he agency does not have to be in writing, it can be implied consent or explicit verbal consent. The promise to acts as an agent is interpreted as being a promise only to make reasonable efforts to accomplish the directed results. The court did not discuss the control aspect in this case. The court found an agency relationship, however they found that he did not guarantee that a credit would be obtained.

Note (p. 13):

(1) A person does not become the agent of another simply by offering help or making a suggestion.

(2) Defining Agency:

(3) The elements of the agency relationship : The agency defines what the responsibility of the principal for actions of the agent. A true agency requires that the agent’s function be the carrying out of the principal’s affairs . The elements of agency include: (i) on behalf of, (ii) principal has control, (iii) both parties consent (implicitly or explicitly).

(4) Electronic Agents :

(5) Proof of Agency : Burden of proof is on the one asserting the existence of an agency relationship. If an agency is to be inferred it must be inferred from a natural and reasonable construction of the facts.

(6)

Ambiguity of the word “Agency ”: What a person can lawfully do for himself, he can do through an agent.

A) Agency or Sale (p. 19):

Hunter Mining Laboratories, Inc. v. Management Assistance, Inc. (p. 19)

Notes (p. 21): There was no agency relationship, only a buyer/seller arrangement. What is missing is that the distributors are acting out of their own interests and not in the interests of MAI.

Notes (p. 21)

(1)

Two key elements of the agency relationship are “control” and “on beha lf of”. Control plays a big roll in analysis of the courts

(2) One who receives goods from another for resale to a 3 the other’s agent in the transaction. rd party is not

(3) The controlling creditor : A trade creditor can become liable as the defacto principal of an agent if they have a lot of control over another.

B) Agency and the Law of Trusts (p. 22): A trust is a fiduciary relationship with respect to property, subjecting the person by whom the title to the property is held to be equitable duties to deal with the property for the benefit of another person, which arises as a result of a manifestation of an intention to create it. a) A fiduciary is a person having a duty, created by his undertaking, to act primarily for the beneift of another in matters connecte4d with his undertaking. b) A Trust involves control over property.

(a) Title:

(b) Control:

(c) Liability:

(d) Consent: An agency is created by the consent of the principal and agent. Trust may be created w/o the knowledge or consent of the beneficiary or trustee.

(e) Termination: Agency can be terminated at will by either party. A trustee is not terminable at will by the beneficiary of the trust.

(f) Agent May Also Be Trustee:

C) Agent or Escrow Holder (p. 24): a) Nature of escrow (p. 24): Because of the arrangement between the parties the escrow holder is not subject to the will of either o

the parties until the specified matter takes place in accordance with the agreement of those for whom he holds it. b) When the escrow succeeds or fails (p. 24): If the event takes place which is to complete the transaction, the escrow holder becomes the agent in possession of the property.

Notes (p. 25) c) Escrow holder distinguished from agent (p. 25):

(1) This would be an agency between X (principal) and A (agent).

(2) All parties were part of the arrangement, therefore it was an escrow arrangement according to Rest. §14 D.

(3) King v. First Nat’l Bank : This was an agency relationship, not an escrow holder. To be an escrow arrangement they would have had agreement by all parties.

(4) Paul v. Kennedy

: Brenner was Kennedy’s agent and held Paul’s money in escrow until the sale of the business went through. Brenner stole the money. Kennedy claimed that he was not responsible because Brenner was only an escrow holder. The court found Brenner to be the agent and Kennedy had to sell his business to Paul.

D) Dual Agency; The Ambiguous Principal (p. 27): a) The Dual Agency Rule (p. 27): An agent cannot act on behalf of the adverse party to a transaction connected with the agency without the permission of the principal.

Thayer v. Pacific Elec. Ry .: RR went to shipper because bill was not paid by

Thayer. RR noted on shipping bill that the shipment was damaged. Shipper filed a written claim for damages with the RR. The RR’s defense was that there was a time limitation on claims filed. The Shipper argued that the RR knew of the damages and the court could excuse that fact that the time limitation was exceeded. The court said since it was an express condition regarding the time limitation, there was no excuse. The Shipper argued that the employee of the RR became an agent for the Shipper that the RR damaged the goods. The consent issue is jumped out because the consent was implied by the RR that it is possible for the clerk to be an agent for both parties for different reasons. Consent was i mplied that the clerk’s duty was to review claims and not out of line with his regular job. Therefore there was a writing by the Shipper (the RR clerk). b) The Ambiguous Principal Problem (p. 28) The question here is whose agent is it? The typical case is that employer is administering an insurance policy and an error occurs where the employee thinks he is covered and he isn’t . The employee says that the employer is an agent of the insurer and therefor the insurer is liable. The insurer is saying the that employer is the employees agent. The majority rule is that an employer is the agent of the insurer and the employee is covered.

Norby v. Bankers Life Co. (p. 29)

E) Sub-agency (p. 31): It may be possible to act through a sub agent.

Sub agency exists when an agent (A) is authorized expressly or implicitly by the principal (P) to appoint another person (B) to

perform all or part of the actions A has agreed to take on behalf of

P. If A remains responsible to P for the actions taken, B is a subagent and A is both an agent (to P) and a principal (to B). B is an agent of P as well as A, which underscores the importance of

P’s express or implied consent to this relationship. (This is typical in real estate-showing broker and listing broker are sellers agents)

F) The History of Agency, and Other Matters (p. 34):

June 2, 1999 Class :

Principal

Agent

Rights and duties flow between the Principal and Agent .

Agent creates legal rights and duties between 3 rd parties and

The principal.

3 rd parties

Equal dignities rule : If I am appointing an agent to create a contract which needs to be in writing in order to avoid the statute of frauds, the relationship between the agent and the principal also must be in writing.

Statutory rules regarding the power of attorney is the creation of an agency relationship. ORC §1337.01 indicates that POA for release of any interest of real property must be in writing. Durable POA is that unlike a CL agency relationship it does not end when the principa l is unable to…. Overall durable POA at ORC

§1337.09 and Healthcare POA is §1337.11.

III. Rights and Duties Between Principal and Agent (p. 39): owed from one party to another. The following case shows how legal relationships change between the principal and 3 rd parties. 3 rd parties can accept an offer directly to the principal or communicate it to the principals agent. The agency is created to benefit the principal. Most of the duties are owed by the agent to the principal. Unequal relationship.

A) Duties of Principal to Agent (p. 40):

1) Duties of Exoneration and Indemnification (p. 40):

Admiral Oriental Line v. United States (p. 40): There were two suits filed. The

United States had made Atlantic its ship’s agent in regards to the “Elkton.”

Atlantic employed Admiral to fitting out the ship on a voyage from the Philippines.

The owners of the cargo of the Elkton sued for losses against Admiral which it defended against successfully. However, Admiral was seeking the expenses to the defense of these losses against Atlantic who in turn said they were not the principal

– the United States was—and it should take responsibility for not only

Admirals expenses in litigation but also Atlantic’s since Admiral was a sub-agent of the US and Atlantic was an agent. Atlantic also sued the US for its expenses in defending itself against the losses of the ship.

Rules : An agent, compelled to defend a baseless suit, grounded on acts performed in his principals business, may recover form principal expenses of his defenses. In equity, before paying debt, a surety may call on principal to exonerate him by discharging debt, and surety is not obliged to make inroads on his own resources when loss must in end fall on principal.

Notes : (p. 42): The court has to find if an agency relationship exists, and if so the agent has the right to be indemnified by the principal.

2) Duty to Pay Compensation (p. 43): Restatement §441 says that where some one is hired as an agent, the principal implicitly infers that he has agreed to pay the agent for services rendered.

Notes : (p. 45)

(a) Agents Lien : Subject to agreement otherwise, an unpaid agent rightfully in possession of property of the principal has a lien upon it for the amount the agent is due from the principal.

(b) Subagents : A subagent is a person appointed by an agent whose empowered to do so, to perform functions and undertake actions for the principal, but for whose conduct the agent agrees with the principal to be primarily liable . (p. 32) If an agent employs a subagent, the agent is the employing person and the principal is not party to the contract of employment, except where, by express promise or otherwise, he becomes a surety. He is not, subject to pay the agreed compensation. (Rest. §458). The distinction between agency and subagency is important only in its effect upon the relations between the principal, agent, and subagent. (Rest. §142 comment b).

3) Duty of Care (p. 45): Principal (employer) is subject to CL duty of care toward agents (employees), arising from its control over the work envi ronment. Principal’s liability does not include exposure at

CL to the strict liability of respondeat superior if one employee through misconduct injures another.

4)

Worker’s Compensation Legislation

(p. 45): requires employers to pay premiums for insurance (or set aside reserves) for compensating employees according to a detailed schedule of recoveries for injuries incurred in the course of employment.

Employees are entitled to compensation even if the injury was not the fault of the employer and even though it was caused solely by the employee’s negligence. If the employee is covered by worker’s compensation they do not retain the CL actions against their employer involving a more certain recovery for damages.

5) Duty to Deal Fairly and in Good Faith

(p. 46): §437 Unless otherwise agreed, a principal who has contracted to employ an agent has a duty to conduct himself so as not to harm the agent’s reputation nor to make it impossible for the agent, consistently with his reasonable self-respect or personal safety, to continue in the employment.

B) Duties of Agent to Principal (p. 46): An agent is a fiduciary and is subject to the directions of the principal. A fiduciary is a person who has a duty, created by his undertaking to act primarily for the benefit of another in matters connected with his undertaking. §13

1) Duty of Good Conduct and to Obey (p. 47):

2) Duty to Indemnify for Loss Caused by Misconduct (p. 47):

3) Duty to Account (p. 48):

4) The Fiduciary Relationship (p. 49): a) Commencement of Fiduciary Relationship (p. 49): A fiduciary duty cannot be imposed on a prospective agent prior to the formal creation of an agency relationship…However, where the very creation of the agency relationship involves a special trust and confidence on the part of a principal in the subsequent fair dealing of an agent, the prospective agent may be under a fiduciary duty to disclose the terms of his employment as an agent. b) Duty of Care

(p. 49): §377 Under ordinary circumstances the promise to act as an agent is interpreted as being a promise only to make reasonable efforts to accomplish the directed result. Reasonable effort is based on the scope of authority conferred, the degree of skill required and the level of competence which is common among those engaged in like business or pursuits. c) Duty of Disclosure (p. 50): An agent owes a fiduciary duty of good faith and loyalty to its principals.

Lindland v. United Business Investments (p. 51): Lindland sold his business through UBI (a business broker). The Buyer did not make payments and the assets of the business were taken over by creditors. Lindland sued UBI claiming that they breached their fiduciary duty of full disclosure regarding the Buyer’s financial status. The lower court said the burden of proof was on UBI and

Lindland recovered. This was reversed on appeal. The S.C. of Oregon said that the burden of proof is on agent in disclosure disputes only if it can be proven that the agent was involved in self dealing or in a conflict of interest . There was no self dealing or conflict of interest alleged or proved in this case. Therefore,

Lindland had only alleged the breach to be nondisclosure of material facts or misrepresentation. Lindland has to establish this as fact, and not allege it. The

S.C. reversed and remanded for a new trial.

Notes :

1) §390 An agent acting as an adverse party with the principal’s consent has a duty to deal fairly and to disclose all facts that the agent should know would reasonable affect the principal’s judgement.

2) The middleman: can work for both parties where an agent cannot deal on the behalf of an adverse party, and the behalf of the principal unless the principal agrees. If no consent there is a breach of the duty of loyalty. d) Duty of Loyalty (p. 53):

(i) Loyalty During the Relationship (p. 54):

Gelfand v. Horizon Corp.

(p. 54): Gefland was terminated by Horizon and sued for unpaid commissions. Trial court found that Gefland was entitled to most commissions claimed. Horizon (on appeal) maintained that Gefland was guilty of a breach of fiduciary duties with respect to one of the sales, which there was no controversy about. The dispute is in the amount of the offset against Gelfand’s claim. Horizon was entitled to an offset not only from the profits that went to

Gefland, but also for profits which accrued to 3 rd part ies (including Gelfand’s wife)

allied with Gefland. The trial court gave damages based on only those profits that went to Gefland. The appeal was for the other 2/3 of profits paid to 3 rd parties.

The law is that an agent occupies a relationship in which trust and confidence is standard. When the agent places his interests above those of the principal there is a breach of fiduciary duty to the principal. The fiduciary is bound to make a full, fair and prompt disclosure to his employer of all facts that threaten to affect the employer’s interests or to influence the employee’s actions in relation to the subject matter of employment.

In this case there was a breach of fiduciary duty. The question is what should the remedy be? The refusal to give Gefland a commission by the trial court was correct. The equitable principle is that a person should not profit from their wrongdoing. The wife’s profit in the transaction is also part of the breach of fiduciary duty and Gefland was using his wife for an indirect gain of profit from the transaction. This money should go back to the principal. However, the trial court found that Gefland is not liable for the profits of the other parties. The law is that a fiduciary who has, by violating his obligation of loyalty, made it possible for others to make profits, can himself be held accountable for that profit regardless of whether he has realized it. The theory is that the agent is free to authorize others to do what he is forbidden. The trial court could have held him responsible for the profits. The trial court’s decision is upheld because:

(1) The court is not obligated to compel a fiduciary to reimburse the beneficiary for 3 rd party profits.

(2) The flexibility and concern for doing justice that are central to equity requires a case by case evaluation of all relevant circumstances. From the evidence and the court’s findings the S.C. said that Horizon did not have a policy which forbade land purchase by employees or required disclosure in such situation.

Horizon employees could get a 20% discount on purchases of unimproved property.

Remedies : (p. 58)

(ii) Post-Termination Competition (p. 60): The CL does not stand in the way of competition, so long as it is fair. One factor that can prove important in assessing fairness of the competition relates to the circumstances under which the employee left the business.

Trade Secrets (p. 61): The use by former employee of information obtained during employment in competition with the former employee. A trade secret is any formula, device, pattern or compilation of information which is used in one’s business, and which gives him an opportunity to obtain an advantage over competitors who do not know or use it.

There is a duty to the principal not to take advantage of a still

subsisting confidential relation created during the prior agency relation.

Covenants Not to Compete (p. 63): These are enforceable if they are ancillary to either the sale of the business or an employment contract. (as long as they are not contrary to public policy). Some states do not enforce these. There is a

balancing test between the employer’s interests, employees ability to earn a living and pubic policy of what is better for the community. Usually look at duration, geography, and burden to the public interest.

June 4, 1999 Class

IV. Vicarious Tort Liability (p. 67): This is the liability of one person for the acts of another; indirect legal responsibility e.g. the liability of employer for the acts of employee.

§6 Restatement of agency : Power is an ability on the part of a person to produce a change in a given legal relation by doing or not doing a given act.

A) The Master-Servant Relationship (p. 67):

1) The Concept (p. 67): All Servants are Agents; All Agents are not

Servants

3 levels of Control :

(1) Master/Servant: Day to day control (Respondeat Superior applies)

(a) Master/servant - master had physical control over agent

(2) Agent: Independent Contractor: Some control (RS does not apply)

(a) Agent: No Physical control (attorneys are agents - clients have no physical control)

(3) Non-Agent Independent Contractor: No control (RS not apply)

(a) Independent Contractor: Some are agents, some are not - depends on facts (i.e. are they acting as agent for principal).

Jones v. Hart (p. 67): A servant to a pawn broker took in goods on behalf of the pawn broker, who said he lost the goods. An action of trover (action for the recovery of damages for a wrongful taking of property or to actually recover the property) was brought against the pawn broker. The question here is who is responsible for the taking of the property?

The court found that the employer is responsible for employee actions, because the employee acts by authority of the master.

Notes : (p. 68):

Is an Employment Relationship Necessary to Respondeat : Superior

Vicarious Liability: This is the liability of one person for the acts of another; indirect legal responsibility e.g. the liability of employer for the acts of employee.

Any employer who hires an employer is liable for their torts. Policy reasons:

Compensate; fairness, spread loss; efficiency.

Vicarious = Employee Negligence and employer/employee relationship.

Corporate Responsibility = Employer Negligence (Neg. hiring, retention) and underlying negligent act causing injury.

Non-Delegable Duty: Inherent Danger or Peculiar Risk of which principal is aware, so can not insulate self from liability by hiring independent contractor (Cars, dynamite, Good Humor Case).

Respondeat Superior Liability?

(p. 70): Respondeat Superior is the doctrine that a principal (master or employer) is liable for injuries proximately resulting from negligent acts of his agent (employee or servant) when the acts are committed within the scope of the agent’s authority or apparent authority of employment. The principal, who is deemed to act through his agents, maintains a duty to conduct his affairs so as not to injure others, and is thus liable for the negligent acts of his agents.

* Must have Master-Servant Relationship

Heims v. Hanke (p. 71): Slip and fall case with ice forming from water spilled.

Rest. 1 Agency (2d) §220. The point in this case is even if there is no business or employment relationship you can still create a master/servant relationship so long as one party has control of the physical activity of another.

Notes : (p. 72): a) Rationale for Respondeat Superior (p. 74):

(i) Arguments Questioning the Theory (p. 74):

(ii) Arguments in Favor or or Explanations for the Theory

(p. 75): b) Imputed Contributory Negligence (p. 76): Vicarious Liability:

Imposing liability on one not negligent per se. Any employer who hires an employer is liable for their torts. Policy reasons:

Compensate; fairness, spread loss; efficiency. c) Limitation to Losses Caused by Tortious Behavior (p. 76):

Liability of the Employee: Indemnification. There is a right to indemnification for the tortious action of the servant, by the master. A failure to follow instructions will indemnify the master

The federal government is not entitled to indemnity from employees for their negligence. d) Direct Tort Liability of an Employer (p. 77)

1) The Independent Contractor Exception (p. 77) Factors the court will look to in determining v. employee: a) Extent of control, b) Distinct nature of workers business, c) specialized skill d) Material and work location e) Duration of employment f) method of payment g) Relation between work and employees regular business h) belief of the parties

If an I.C. is also an agent, then may be liable vicariously (but not for torts unless employer/employee).

2) Borrowed Servants (p. 87): Borrowed Servant: 2 Tests : a) Whose business? Often useless - both benefit. b) Who controlled? Who was in better position to prevent injury?.

The special employer will usually insist on indemnification against any liability by the general employer.

Charles v. Barrett (p. 88): General employer leased a truck and driver to a special employer. The driver negligently hits and kills a pedestrian. The special employer was sued as the employer of the driver. The driver was a borrowed servant of the special employer. The rule is that as long as the employee is furthering the business of the general employer by service rendered to another, there will be no inference of a new relation unless command has been surrendered and no inference of its surrender from the mere fact of its division. In this case the special employer was not found negligent.

Notes : (p. 93): Other cases show just the opposite effect. Where the employee of a general employer and who is now under control of the special employer, the special employer is the one who can be found vicariously liable.

3) The Scope of Employment Limitation (p. 91): Scope of

Employment: Test : Was it furthering the business of the master.

One who leaves the scope then re-enter when the dominant purpose was returning to the masters business. Non-Delegable

Duty : Inherent Danger or Peculiar Risk of which principal is aware, so can not insulate self from liability by hiring independent contractor (Cars, dynamite, Good Humor Case). a) Negligent Acts (p. 91): A wrong must take place during the scope of the employment of the agent. The problems include things like where a delivery person does not follow the instructions of the employer.

Joel v. Morison (p. 91): The rule in this case if you are on a detour you are within the scope of employment and if on a frolic then the employer (master) will not found to be liable.

Bremen State Bank v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co.

(p. 96): Bank moves it operation to a new location. All cash is moved to new location except on drawer. When office equipment moved a mover steals the money that was left behind. The bank sued the general mover as a master when the employee of the mover stole the money. The court said they weren’t liable because there was no benefit to the moving company and the stealing was not in the scope of the employees employment.

June 7, 1999 Class

Stentan v. Ohio Exterminators : Employee of exterminating company stole a ring from house. He is brought out on charges of theft. A few months later employee hired a hit man to kill the homeowner. Found that the employee was not an agent.

B) The Joint Enterprise Relationship (p. 106): In this relationship the doctrine involves vicarious liability for the misconduct of a fellow joint enterpriser in a non-commercial setting. Liability does not depend on control over the manner and means of the conduct of another, nor is action on behalf of the defendant directly required. Liability depends on

being in an enterprise that involves shared purpose and shared control, but control in a broader sense than that involved in respondeat superior.

Howard v. Zimmerman : A joint enterprise is simply a project participated in by associates acting together. The basis of liability of one associate in a joint enterprise for the tort of another is equal. The privilege to control the method and means of accomplishing the common design is shared.

Notes : (p. 107)

C) The Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Relationship (p. 109):

Only 6 states have enacted the Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit

Association Act which declares a nonprofit association a legal entity separate from its members and expressly states that members are not liable in contract or tort for liabilities of the association absent special circumstances (e.g. personal guaranty or personal misconduct). The

Common Law is followed in the rest of the states and is:

1) Liability of the Members (p. 109): The rule is that members of voluntary nonprofit associations are regarded as co-principals of each other. Membership alone does not make a person vicariously liable for torts committed by officers, other members, or employees, a member can become liable by authorizing or ratifying a tortious act. The same rule applies with respect to liability for contracts made by t association.

2) Liability of the Association to Its Members (p. 110): The rule seems to be that of the co-principal doctrine. The concept is that since one cannot base a cause of action on a wrong attributable to him, the association is immune from liability. Exceptions have been found where a member can successfully sue the association and recover assuming the state has legislation allowing the association to sue. This would be based on the concept that if the association acts normally through elected officials and the individual has little or no authority in the day to day operation of the associations affair, the member would be allowed to sue the association.

Skim the following:

D) Vicarious Liability and Estoppel (p. 110): (Also known as apparent agency) Some courts have required that the 3 rd party prove that the principal held itself out to the public as the provider of services and that the 3 rd party did not know that the individual providing the services of the principal was an independent contractor and not an agent of the principal.

(1) Implied agency would be the counter to this type of defense on the part of the 3 rd party. They could argue that the agency was created by the acts of the parties and deduced from proof of other facts. It then becomes an actual agency, proved by the deductions or inferences from facts, and the third party need have no knowledge of the principal’s acts, nor have relied on them.

Crinkley v. Holiday Inns, Inc.

(p. 111):Crinkley’s were robbed and had the crapped kicked out of them at a Holiday Inn (HI) which was run by TRAVCO on behalf of a franchisee. Crinkley’s sued HI and others. HI defended on basis that there was no actual agency relationship (agreed to by courts) and there was no apparent agency (which court did not agree with). Apparent Agency (Agency by

Estoppel) could hold HI on the basis that they had been held out by the other to be so in a way that reasonably induces reliance on the appearance. The P must show that (1) the alleged principal has represented or permitted it to be represented that the party dealing directly with the plaintiff is its agent, and (2) the plaintiff, in reliance on such representations, has dealt with the supposed agent. Rest. §267. The evidence is marginal but was held enough by the court.

June 7, 1999 Class

V. Contractual Powers of Agents (p. 117):

A) Authority (p. 117): is the right, permission, or power to act, as in permission a principal gives to his agent to act in his behalf. Authority can be “

Express

” ( i.e.

that which is explicitly given as in a POA); it can be “ Implied ” as in that which can be inferred from a person’s conduct or from cir cumstances; and it can be “ Apparent ” as when a principal permits an agent to act.

Rest. §7 Authority

is the power of the agent to affect the legal relations of the principal by acts done in accordance with the principal’s manifestation of consent to him.

1) Express Authority (p. 117): The words used in granting construed strictly. For example, a statement granting general power of attorney, but strictly limiting the scope of the power in a particular area.

King v. Bankerd (p. 117):

Issue : Whether a POA, authorizing the agent to “convey, grant, bargain and/or sell” the principal’s property authorizes the agent to make a gratuitous transfer of that property.

Rule : POA is a written document by which one party, as principal, appoints another as agent (attorney in fact) and confers upon the latter the authority to perform certain specified acts or kinds of acts on behalf of the principal.

Analysis : POA rules are held to grant only those powers which are clearly delineated. But the court must determine the intention of the parties when looking at the POA. Ambiguities in a POA should be resolved against the party who made the POA or caused it to be made, because the party had the better opportunity to understand and explain his meaning. An agent holding a broad

P OA lacks the power to make a gift of the principal’s property, unless that power

(1) is expressly conferred; (2) arises as a necessary implication from the

conferred powers, or (3) is clearly intended by the parties, as evidenced by the surrounding facts and circumstances.

Finding: The facts and surrounding circumstances presented in the case do not give rise to any fact or inference that King was authorized to make a gift of

Bankerd’s real property. There is not dispute in the material facts. The trial court was correct. .

2) Implied Authority (p. 123): Power implied by custom, usage, or conduct of the principal which shows an intention to authorize an act. a) Delegation of Authority (p. 123): Normally an agent owes the principal a duty to personally discharge his employment and thus is unable to delegate his authority unless the principal so consents., or the particular circumstances of the case indicate that the principal’s consent could reasonably be implied. b) Incidental Authority (p. 124): Unless otherwise agreed, authority to conduct a transaction includes authority to do acts which are incidental to it, usually accompany it, or are reasonable necessary to accomplish it. An agent who has authority to borrow has incidental authority to give a promissory not e in the principal’s name. It is inferred that the principal is not doing a vain thing, but intends to give a workable and effective consent. It is not essential to the authorization of an act that the principal should have contemplated that the agent would perform it as incidental as the authorized performance.

3) Authority in the Restatement (p. 124)

B) Apparent Authority (p. 125): Apparent Authorization (Ostensible

Authority) The conduct of the principal in holding out" the agent as having authority which he has not actually given. Damages are contractually based, rather than estoppel. Based on the person who enables the apparent authority will be found liable.

Smith v. Hansen, Hansen & Johnson, Inc.

(p. 125):

Rule : Actual and apparent authority depend on objective manifestations which must be those of the principal.. With actual authority, the principal’s objective manifestations are made to the agent; with apparent authority, they are made to a 3 rd person. Manifestation to a 3 rd person can be made by the principal in person or through anyone else including the agent, who has the principal’s actual authority. To make them. The manifestation must (1) cause the one claiming apparent authority to actually believe that the agent has authority to act for the principal. (2) They must be such that the claimants actual, subjective belief is objectively reasonable.

Conclusion

: HH&J’s beliefs were not reasonable. The glass was not in the control of Fentron, and Foster insisted that payment be made to him, not

Fentron.

Sauber v. Northland Insurance Co.

(p. 132):

Issue: Can one presume the person answering the phone has the authority for any duties assumed by the employee?

Holding: Yes. When an employee of a business is authorized to answer calls coming over the telephone, the burden of proving lack of authority should rest on

the one who has placed the employee in the position, where others would rely on the apparent authority. McDonald cannot deny the authority.

By putting someone in the position to answer questions of the coverage, you clothe them with the authority.

This is apparent authority - the third party acted in good faith, with a person who discussed apparent authority.

June 9, 1999 Class

C) Estoppel (p. 137): Where the agent has been held out as having the power, there was reasonable reliance by the third party, then there was actual reliance by the third party, and change in position to his detriment. (intent, reasonable reliance, actual reliance, damages). It is like apparent authority, except damages are based upon loss due to the reliance.

Hoddeson v. Koos Bros.

(p. 137): Lady went into a furniture store, person comes up and takes order. She pays for it and the furniture never comes. She finds out that the salesperson was not an employee of the furniture store. There is no action or authorization by the company that would have made her believe that the person was an agent. The theory that was tried on was that of agency.

The court said that they were going to estopp the furniture company from denying an agency. The reason is that where the agent has been held out as having the power, there was reasonable reliance by the third party, then there was actual reliance by the third party, and change in position to his detriment.

(intent, reasonable reliance, actual reliance, damages). It is like apparent authority, except damages are based upon loss due to the reliance.

D) The Inherent Agency Power Concept (p. 142): Powers which a third party would reasonably expect the agent to possess under the circumstances. There must be an existing general agency, an act within the scope of authority of similar agency relationships, an unauthorized act of the agent with no holding out by the principal, and reasonable belief. (agency, act within scope, act beyond scope, belief).

One example of the is Respondeat Superior or in Contract law (p.

142).

1) The Concept (p 142): An agent can bind the principal to contracts where there is neither authority nor apparent authority and where the agent is acting disobediently, so long as the ac ts done “usually accompany or are incidental to “transactions which the agent is authorized to conduct. §161.

2) The Rationale for the Concept (p. 143): If a man selects another to act for him with some discretion, he has by that fact vouched to some extent for his reliability. The purpose of delegated authority is to avoid constant recourse by 3 rd persons to the principal, which would be a corollary of denying the agent any latitude beyond his exact instructions . Kidd v. Thomas A. Edison, Inc ., 239 F. 404 (2d.

Cir. 1917).

Croisant v. Watrud (p. 143): The Plaintiff hired the Defendant partnership to advise on tax matters and prepare income tax returns. When P sold her business she made a contract with D to make collections under the sales contract. P found out later that her husband had induced D to make unauthorized payments out of some of the proceeds. She also found out that D , w/o authorization had drawn checks to himself. When D was confronted he admitted the abuse of his trust.

Soon after D died. P filed suit against his partners. The trial court held that D was acting as an independent trustee employment, separate and distinct from the activities in which the partnership was working. The tax advice and preparation was definitely part of the firms work. But the partnership was sattled with the liability anyway because there was an existing general agency, an act within the scope of authority of similar agency relationships, an unauthorized act of the agent with no holding out by the principal, and reasonable belief. (Inherent agency power.)

Problems (p. 148) 1 & 5

(1) Is this w/i the power of the agent to bind the principal? The focus is on whether the 3 rd party thinks that the agent has power. The agent acted has not obeyed the principal and this is a breach of the agent’s duty. This is binding though, through apparent Authority (Ostensible Authority) The conduct of the principal in holding out" the agent as having authority which he has not actually given. Damages are contractually based, rather than estoppel. Based on the person who enables the apparent authority will be found liable. The manifestation must (1) cause the one claiming apparent authority to actually believe that the agent has authority to act for the principal. (2) They must be such that the claimants actual, subjective belief is objectively reasonable .

(5) See: Hoddeson : Where the agent has been held out as having the

power, there was reasonable reliance by the third party, then there was

actual reliance by the third party, and change in position to his detriment.

(intent, reasonable reliance, actual reliance, damages). It is like apparent

authority, except damages are based upon loss due to the reliance. The

3 rd parties would not be liable to the principal (i.e. they would not have to

take the magazine in lieu of getting their money back). Counter argument

is that even though there is a duty to act, by ACE (otherwise Estoppel by

silence), it may make it impossible for them to act if he was going around

the country.

VI. Fraudulent Acts of Agents (p. 153):

A principal is charged with the knowledge of his agent, a concealed defect is not a statement or misstatement, but a concealment, and thus an exculpatory clause will not hold. You cannot exculpate fraud.

A) The Unscrupulous Agent (p. 153):

Entente Mineral Co. v. Parker (p. 153): The proper inquiry for determining vicarious liability of a principal whose agent defrauds the principal’s customer is the relationship between the principal and the customer. The principal must have a relationship with the customer and customer was defrauded by the principal’s agent. The idea is that the principal was the one who provided the agent with the

tools or position necessary to perpetuate a fraud on the principal

’s customers, should be held responsible to the innocent customers who relied on the agent. In this case there was no relationship between the firm and Entente that could be imputed to the firm’s agent. Neither Parker nor the firm represented Entente.

The court looked at Rest. §219(1) Whether the agent was acting in the scope of employment and referred to §228(1)(c) and said there was no purpose to serve

Entente. The 2 nd area reviewed was under §219(2) in that the agency relationship which Parker had with the firm did not aid him in committing the alleged tortious act against the firm. The firm was not getting part of the property

Limits to Liability for Fraud (p. 160): If the principal is not benefited, and the transaction which actually causes loss is not one in which the agent purports to represent the principal, liability will not follow to the principal.

B) The Exculpatory Clause (p. 164): A clause in a trust instrument that relieves a trustee from liability when he has acted in good faith.

Eamoe v. Big Bear Land & Water Co.

(p. 164): There was a purchase of land.

Person wants to buy land and are told they are getting specific land, the buyer believes that this is his land and starts building on land which is not his. This person sues D because they gave him directions to the wrong lot and he lost what he built. The company tried to avoid liability under a merger clause. The court said that it is possible for a company to insulate themselves from the liablity of the contract. The purchaser can rescind the contract, but no damages or as in this case, the buyer can collect damages because unlike Spec the court says the scope of the exculpatory clause is intended to limit the principal’s liability from representations outside the agents authority. The court said that representing the exact location of the property is within the scope of the agents authority from the principal.

Dembowski v. Central Construction Co.

(p. 166): The point in this case is a siding salesman says that the customer does not have to pay for the siding because it will be a model home. The written contract disallowed this and disaffirmed any agreements like this, but the customer signs. The contractor wants to collect and the customer says they don’t have to pay, the court said that the contract could be rescinded prior to a change in position by the principal, but once the siding was put on the customer has to pay.

King v. Horizon Corp . (p. 168): Horizion was selling land to customers and employees made representation that the land was worth $75K. The representation was false and known by the salesperson. There was exculpatory language in the document.. The King’s signed the document. Was the principal liable? The exculpatory language did not hold water, because the principal knew of, accepted the fruits of the fraud, and even encouraged the fraudulent representations. The principal cannot hide behind the exculpatory clause.

Problems (p. 171):

(2) Look to §219(2)(d) and 261 would show vicarious liability by a principal for it’s agent’s fraud.

June 14, 1999 Class

Principal

Agent 3 rd Party

VII. The Undisclosed Principals (p. 173): if, at the time of a transaction conducted by an agent, and the other party has notice that the agent is acting for a principal and of the principal’s identity, the principal is a disclosed principal . If the other party has notice that the agent is or may be acting for a principal but has no notice of the principal’s identity, the principal is partially disclosed . If the other party has no notice that the agent is acting for a principal, the one for whom he acts is an undisclosed principal

Rest. 2d Agency §4

A) Rights of the Undisclosed Principal (p. 173): A person who makes a contract with an agent of an undisclosed principal is liable to the principal as if the principal himself had made the contract with him unless he is excluded by the form or terms of the contract, unless his existence is fraudulently concealed or unless there is a set-off or a similar defense against the agent. This goes against contract theory that contract liability is based on a mutual manifestation of consent.

1) Assertion of Rights by the Undisclosed Principal (p. 174): An undisclosed principal may sue on his own behalf for the breach of a legal duty in a contract and may claim benefits of such contract.

Since an undisclosed principal is treated as a party to the contract with respect to the obligations and benefits under the contract, it follows that the principal would be entitled to raise the a defense of usury (the lending of funds at exorbitant rate or at a rate above that permitted by the law) absent a statute to the contrary.

2) Parole Evidence Rule (p. 175): Parole evidence does not deny that a contract binds those whom on its face it purports to bind, but shows that it also binds another, by reason that the act of the agent is the act of the principal. Parole evidence is forbidden if the contract by its terms excludes the principal as a party. §190

3) Exceptions (p. 176): If a person knows that the party he wants to contract with will not deal with him due to personal enmity (hostility) and that person hires an agent to enter into the transaction on his behalf but with instructions not to disclose the fact the he is doing so. The principal has the right and duties that were negotiated by the agent. See the next case.

Kelly Asphalt Block Co. v. Barber Asphalt Paving Co.

(p. 176) A contract not under seal, made in the name of an agent as ostensible principal, may be sued on by the real principal at their election. The principal and defendant were competitors. The principal was undisclosed. The products purchased were unmerchantable and D said that he should not be held liable because he did not know who the principal was, and said he would not do business with the principal

if he had known who he was. There was no evidence that D had ever done or refused to do business with the Principal. The court said that there was an apparent meeting of the minds between the determinate parties in this contract,

The D was contracting w/ the person whom they intended to contract, Booth. D was paid what was agreed to. An agent who contracts in his own name for an undisclosed party does not cease to be a party because of his agency. The agent himself would be personally liable and could enforce the contract even if the principal would reject the contract. The non disclosure of Booth regarding his acting as an agent for Principal, would not nullify the contract. Since the contract would not fail for want of parties to sustain it, the unsuspected existence of an undisclosed principal can supply no ground for the avoidance of a contract unless fraud is proved. Fraud only becomes important when a sale or contract is complete in the formal elements, and valid unless repudiated but the right is claims to rescind it. If Booth has said he was the principal and not the agent, this could be fraud. However, Booth never said what he was. He wasn’t asked and he did not say anything regarding his role.

Finley v. Dalton (p. 179): Dalton approached Finley with an offer to buy land.

Finley asked why he wanted it and he said for an investment for his kids. In reality Dalton was acting as an agent for Duke Power Company. Finley allegedly that the land was worth a lot more if Duke was going to buy if versus if Dalton was buying it for himself. A misstatement of misrepresentation as to the use of land made in the negotiation for it’s purchase does not necessarily constitute fraud, especially the use for a different purpose from that stated does not injure the seller by reason of his ownership in other land in the area. Court found that the misrepresentation was not material to the sale of the land. The seller received FMV for the land and the sale was not detrimental to the seller.

Notes : (p. 180)

B) Liabilities of the Undisclosed Principal (p. 181):

1) Authorized Transactions (p. 181): Rest §186 The principal is bound by the contract and can be sued by the party contracting with the agent. The theory behind this rule is that since the principal “is the one who initiated the activities of the agent and has a right to control them” he is liable “in accordance with the ordinary principles of agency.” a) Remedies of the Third Party (p. 182): are the customary contract remedies against the agent. The agent signed the agreement as a contracting party. The fact that the 3 rd party didn’t know about an undisclosed agent does not reduce his contractual obligations. The undisclosed principal is liable to the

3 rd party in accordance with principles of agency law. b) The Election Rule (p. 182): It is procedurally possible to join both the agent and the principal in a suit, in the majority of jurisdictions however, the 3 rd party is forced to choose from whom it wishes to obtain judgement.

2) Unauthorized Transactions (p. 183): Estoppel may take precedence (p. 137): Where the agent has been held out as

having the power, there was reasonable reliance by the third party, then there was actual reliance by the third party, and change in position to his detriment. (intent, reasonable reliance, actual reliance, damages). It is like apparent authority, except damages are based upon loss due to the reliance. Inherent Agency Power could make the true owners liable . Powers which a third party would reasonably expect the agent to possess under the circumstances. There must be an existing general agency, an act within the scope of authority of similar agency relationships, an unauthorized act of the agent with no holding out by the principal, and reasonable belief. (agency, act within scope, act beyond scope, belief). One example of the is Respondeat Superior or in

Contract law. No Apparent Authorization in the case of undisclosed principals.

(Ostensible Authority) The conduct of the principal in holding out" the agent as having authority which he has not actually given. Damages are contractually based, rather than estoppel. Based on the person who enables the apparent authority will be found liable

Watteau v. Fenwick (p. 184): Humble ran a business as if it were his own, and in fact was managing the property for principals. Humble was told that he only had the authority to purchase bottled ales and mineral waters all other goods would be purchased by the principals. Humble purchased cigars and other items from third party w/o disclosing his position or who the principals were. The question here: are the undisclosed principals liable for the bills. The trial judge found that the principals owed the Ds for the goods.

Payment and Setoff

1)

(p. 190):

Payment by the 3 rd Party

(p. 190): Rest. §307(1)(a) Until the existence of the principal is known, the agent has the power to rescind, perform and receive performance of the contract and to modify it (if the modification) is within his agency powers.

2) Payment to the 3 rd Party (p. 190) The majority rule is that if payment is made in good faith by an undisclosed principal to an agent for settlement of an obligation incurred by the agent is sufficient to protect the principal. The minority rule is in Rest. §208:

An undisclosed principal is not discharged from liability to the other party to a transaction conducted by an agent by payment to, or settlement of accounts with, the agent, unless he does so n reasonable reliance upon conduct of the other party which is not induced by the agent’s misrepresentations and which indicates that the agent has settled the account.

3) Setoff

(p. 191): Rest. §306 (1) If an agent has been authorized to conceal the existence of the principal of a person dealing with the agent within the power to bind the principal is diminished by any claim which such person may have against the agent at the time of making the contact and until the existence of the principal becomes known to him, if he could set off such claim in an action against the

agent. (2) If the agent is authorized only to contract in the principal’s name, the other party does not have set-off for a claim due him from the agent unless the agent has been entrusted with the possession of chattels (an item of personal property- e.g. a car stereo) which he disposes of as directed or unless the principal has otherwise misled the 3 rd person into extending credit to the agent. a) Set-0ff is a counterclaim demand brought by a D, extrinsic to the cause of action to reduce the amount of the P’s recovery; e.g. a counterclaim demand based on a breach of contract brought by the 3 rd person against the agent in an action for the purpose of reducing the agent’s possible recovery. b) Recoupement is the 3 rd person’s right to recover part of the agent’s award of damages against the principal by reducing the agent’s claim due to previous payment by the 3 rd person or agent’s own wrongful or defective performance of the contract.

Branham v. Fullmer (p. 192):

Problems (p. 193):

VIII. Liability of the Agent to the Third Persons (p. 195)

A) Liability on the Contract (p. 195)

1) Liability When the Principal is Un-intentionally Undisclosed (p.

195)

Jensen v. Alaska Valuation Service (p. 195)

Notes (p. 196)

2) Liability When the Principal Is Disclosed: Special

Circumstances (p. 197)

Notes (p. 198)

June 16, 1999 Class(pp. 200-229)

3) Liability When the Principal is Partially Disclosed (p. 200)

Van D. Costas, Inc. v. Rosenberg (p. 200)

Notes : (p. 201)

B) The Agent’s Warranty of Authority (p. 204)

Notes : (p. 205)

C) Harm to the Economic Interests of Others (p. 206)

Notes : (p. 207)

D) Liability in Tort (p. 207)

Problems (p. 207)

IX. The Doctrine of Ratification (p. 209)

A) The Concept (p. 209)

Evans v. Ruth (p. 209)

Dempsey v. Chambers (p. 211)

1) Justification for the Concept (p. 212)

Notes : (p. 213)

2) Implied Ratification (p. 215)

Manning v. Twin Falls Clinic & Hospital, Inc.

(p. 215)

Notes : (p. 216)

B) The Knowledge Requirement (p. 217)

Notice and Knowledge:

*General Rule: Knowledge of the Agent is imputed to the principal.

Exceptions: Outside directors (they are not employees or officers).

Exception: If agent commits fraud (weak hearted horse case).

Exception: Knowledge not imputed if agent is a dual agent for both parties.

Exception: If agent acting adverse to principal, and for benefit of self or some other beside principal, then his knowledge will not be imputed.

Exceptions: If agent acting adversarial to principal

Exception to the Exception: Sole Actor Doctrine

When agent, only actor in transaction or such dominance over principal that knowledge is imputed to principal.

Above Exceptions apply only to knowledge, not notice.

*General Rule: Notice to Agent is imputed as notice to the principal.

Notice is enough without knowledge, but reverse is not true.

Undisclosed Principal: Notice to agent does not bind principal; agent is personally liable to third parties; Agent would then be a party to K.

Partially Disclosed Principal: The fact that you are an agent is known, but principal unknown.

Disclosed Principal: Agent not personally liable;

Exception: Atty agent can be personally liable.

*Majority Rule: If you know principal, but seek and obtain judgment from agent, principal is res judicata (have to elect somewhere in the proceeding)

Minority: One recovery; can keep suing until satisfied.

Computel, Inc. v. Emery Air Freight Corp.

(p. 218)

C) Can Silence Constitute Affirmance?

(p. 220)

Bruton v. Automatic Welding & Supply Corp.

(p. 220)

Notes : (p. 224)

D) The No Partial Ratification Rule (p. 225)

Miscellaneous Notes : (p. 226)

E) Changed Circumstances (p. 226)

Notes : (p. 226)

Problems : (p. 228)

June 21, 1999 (pp. 229-247)

X. Notice and Notification; Imputed Knowledge

(p. 231): See UPA §02

A) Introduction (p. 231): Notice indicates the legal consequences

B) Notification (p. 231)

C) Imputed Knowledge (p. 233):

Notes : (p. 234)

D) The Adverse Interest Qualification (p. 235)

Farr v. Newman (p. 237)

E) The Sole Actor Doctrine (p. 240)

Munroe v. Harriman (p. 241)

Notes : (p. 244)

Problems : (p. 245)

XI. Termination of the Agency Relationship (p. 249)

A) Termination Between the Parties to an Agency Relationship (p. 249)

1) Termination by Will (p. 249) a) Some Consequences of Termination of an Agency Relationship

(p. 250) b) Irrevocable Powers Phrased in Agency Terms (p. 250)

2) Termination by Operation of Law (p. 251) a) Death (p. 251)

Hunt v. Rousmanier’s Administrator (p. 251) b) Loss of Capacity (p. 253)

B) Notice of Termination to 3 rd Parties (p. 254)

1) Termination by Will (p. 255): Principal has to give actual notice to

3 rd person who the agent has dealt with in the past. As per other agents, constructive notice is enough. Expectations of the 3 rd person to apparent authority must be reasonable.

2) Termination by Operation of Law (p. 256): Most courts feel that actual and apparent (all) authority is cut off by death.

Problem (p. 257)

XII. The Creation of a Partnership (p. 259)

A) Introduction (p. 259):

B) The LLP (p. 260):

C) The Partnership Relationship Defined and Distinguished From

Other Relationships (p. 262):

1) An Early Test of Partnership (p. 262):

2) Partnership and Mutual Agency (p. 262):

3) The Uniform Partnership Act (1914) and the Revised Uniform

Partnership Act ( 1994 ) (p. 263):

Martin v. Peyton (p. 267):

D) The Underlying Theory of Partnership

– Aggregate or Entity?

(p.

273):

E) Income Tax Consideration – A Brief Summary (p. 277):

June 23, 1999 Class:

Partnership: is a voluntary agreement between two or more competent persons to place their money, effects, labor and skill, or soe or all of them, in lawful commerce or business, with an understanding hat any profit or loss shall be divided in certain portions.

An association of 2 or more persons to carry on as co-owners a business for profit.

Entity or Aggregate?: how is a partnership viewed.

Aggregate view : If a partner leaves then a new partnership is formed

Entity view : If a partner leaves, a partnership continues. There is a reluctance to viewing partnerships in this way.

F) Contribution of Property to the Partnership (p. 278):

1) Ambiguities Concerning Ownership of Particular Property (p. 278):

UPA

§8(1) states that property brought into partnership stock or purchased on account of the partnership is partnership property.

§8(2) Unless the contrary intention appears, property acquired with partnership funds is partnership property.

RUPA :

§203 & 204: Similar ideas as UPA.

2) The Special Matter of Title to Real Property (p. 280): At CL a conveyance of land to the partnership is allowed. Courts treat land differently depending on the state. UPA §10, RUPA §302 go into detail n this.

3) The Property Rights of a Partner (p. 281):

Putnam v. Shoaf (p. 282): Putnam had real and personal property that was transferred via Quit Clam Deed to the partnership. The partnership sued banks for malfeasance and won $68K. Putnam then claimed that property was her asset and wanted to be paid for it. Court said that the land was a partnership asset. The approach was an entity type approach. UPA §24 & 25 defines the property rights of partners in various ways.

Problems : (p. 286):

Perry Corp. argument:

RUPA §202(a); §202(c) would indicate that both were partners implicitly.

This section helps to delineate between agency (claimed by both) v. partnership, and clearly by their actions both are partners.

Others:

They were agents and interested investors in the business and nothing more. As employee (agent) and investors they were not involved as laid out

Proprietorship Partnership

No documentation or No documentation filing is essential to existence or filing is essential to existence

No initial and annual No initial and franchise or license tax annual franchise or license tax

Limited

Partnership

No initial and annual franchise or license tax

Limited Liability

Corporation (LLC)

Corporation

Documentation and Documentation and filing is essential to existence filing is essential to existence

Initial and annual franchise or license tax

Owner's liable for business debts

Judicial proceedings in the name of the individual owner

Owner's liable for business debts

Limited partners

Partners and and shareholders are not individually liable shareholders are not individually liable

Judicial proceedings

Judicial proceedings in the in the name of all partners name of general partners

Judicial proceedings in the name of the corporation

Documentation and filing is essential to existence

Initial and annual franchise or license tax

Partners and shareholders are not individually liable

Judicial proceedings in the name of the corporation

Transfer of ownership requires conveyancing formalities

Transfer requires consent of the partners

Transfer may be done freely and informally

Shares may or may not be freely negotiable

Shares freely negotiable

Authority and

Distributed profits taxed as income of members

Enterprise profits taxed even though undistributed

Enterprise losses offset against members' individual taxable incomes

Ownership and ownership terminates authority impaired at death of owner at death of partner

Distributed profits taxed as income of members

Enterprise profits taxed even though undistributed

Ownership and authority impaired at death of general partner

Distributed profits taxed as income of members

Enterprise profits taxed even though undistributed

Enterprise losses

Enterprise losses offset against offset against members' individual taxable incomes members' individual taxable incomes

Ownership and authority may be impaired at death of member or limited by other means

Ownership and authority unaffected by death of member

Distributed profits taxed as income of members

Enterprise profits taxed even though undistributed

Enterprise losses offset against members' individual taxable incomes

Distributed profits taxed once as corporate income and again as income of members

Undistributed profits taxed only as corporate income

Enterprise losses not offset against members' taxable incomes

May or may not have May or may not centralized management have centralized management

May or may not have centralized management

May or may not have centralized management

Centralized

Management

XIII. The Operation of a Partnership (p. 291)

A) Contractual Powers of Partners (p. 291) Partners can own property.

They have a right to enjoy the property. Unless otherwise agreed, property purchased with partnership assets is partnership property, even if contributed by one partner. Partner's interests in partnership assets are personalty. Personalty does not have a dower and the signature of the other spouse is not required. The interest of the property does not pass on death, but the partnership interest passes.

The value of the property is considered upon death. personalty is anything that is not realty. partners had an interest in the partnership.

The partnership had the interest in the realty.

1) Actual Authority (p. 291)

Summers v. Dooley (p. 292) Summers and Dooley were partners in a trash hauling business. Summers felt they needed a third man, and hired someone,

paying him out of his own pocket. Dooley objected to the third man. Summers sued for payment.

Issue: Does an equal partner in a two man partnership have the authority to make unilateral decisions in disregard of the objection of the other partner, and then attempt to charge the dissenter with the costs of the decision?

Holding: No. In absence of an agreement to the contrary, a business decision must be made by a majority of the partners.

Judgment: Affirm

National Biscuit Co. v. Stroud (p. 294):

Dissolution before any orders were issued to National Biscuit is the only course of action which Stroud could take in order to avoid paying the bill to National

Biscuit. Under UPA 31, dissolution is available in partnerships, with damage going to the dissolving partner.

UPA §18 The rights and duties of partners to the partnership, including sharing of profits, losses, assets and liabilities; right to indemnification; right to manage; consent to add partners; majority rule.

2) Apparent Authority (p. 296)

Burns v. Gonzales (p. 296): Partnership sold radio air time. Sold air time to

Burns and there was an agreement by one of the partnerships to execute a promissory note to Burns which is not paid. Assuming there is no actual authority by the partner who issued the note, the partnership under §9(1) could be bound by apparent authority. However, the court found that there was no evidence of apparent authority (manifestation to the 3 rd party that there is apparent authority).

3) Partners Liability by Estoppel (p. 301) Where the agent has been held out as having the power, there was reasonable reliance by the third party, the was actual reliance by the third party, and change in position to his detriment. (intent, reasonable reliance, actual reliance, damages). It is like apparent authority, except damages are based upon loss due to the reliance.

Hypothetical (p. 301): a) Is There a Duty to Speak?

(p. 302) A claim of ratification could make a person liable in the partnership, even though none exists. A person who knows of an unauthorized act can affirm thro ugh inaction, that is, by failing to repudiate the act “under such circumstances that, according to the ordinary experience and habits of men, one would naturally be expected to speak if he did not consent. Rest. §94. b) The Reliance Conundrum (p. 304): Partnership by estoppel is tough to enforce if a person neither made nor consented to a misrepresentation prior to a 3 rd parties reliance on that misrepresentation (UPA 16(2 ). In contrast, UPA §16(1) could apply to the initial partners and make them accountable for the debts, jointly and severally, by representing themselves as having the authority to bind a partnership (even if it did not exist)

June 25, 1999 Class (pp. 307- 337) PARTNERSHIP RULES (AGENCY RULES

STILL APPLY)

Third Party v. Partnership

UPA 9, 13, 14

RUPA 301, 303, 305

Third Party v. Partners

UPA 15

RUPA Article 10, §306

ORC 1775.14

Partner v. Partner

UPA 18-21

RUPA Article 4

B)

Tort Liability for the Wrongs of Partners (UPA§13)

(p. 307): UPA

§13 states a rule or attributing certain “wrongful” acts or omissions of a partner to a partnership.

(1) The provision is used to sue a partnership of a professional for malpractice of one of the partners, or to sue a partnership for damages caused by a partner (i.e. auto accident).

(2) The partnership is liable to the same extent as the partner so acting or omitting to act.

(3) The attribution rule applies to torts of negligence and intentional torts but does not apply to wrongs by one partner to another.

C)

The Nature of a Partner’s Liability – Joint as Opposed to Joint and

Several Liability (p. 312)

(1) Vicarious Liability - The tortious act of one person may be imputed to another because some special relation existed between the two. In agency, the tortious acts of an employee acting within the scope of his employment will hold the employer vicariously liable for the tort. Vicarious liability can be found in a partnership, a joint enterprise or even a family relationship where there is some common family purpose involved.

(2) Respondeat Superior - an employer may be liable for misfeasance, non-feasance, intentional tort or misrepresentation. Intentional torts are a bit more difficult to impute liability.

(3) A principal is not liable for harm caused by a non-servant agent who is acting within the scope of his authority because the principal does not have the legal right to control any of the details of the physical performance.

D) Suits Against the Partnership (p. 313): All partners are liable jointly and severally for everything chargeable to the partnership under UPA

(RUP A) §§13; 14(305(b)); (§15(§306)). They are also jointly liable for all other debts and obligations of the partnership; but any partner may enter into a separate obligation to perform a partnership contract.

E) Suits by the Partnership (p. 314)RUPA 310 says that partnerships must bring suit in the name of all partners since only legal persons may be named as parties in litigation.

F) Notice and Notification to the Partnership

(p. 314): UPA §§3, 12

(RUPA 102) Knowledge is subject (means actual knowledge). Notice is actual notice when we know of something. We can have notice through actual knowledge of by notification.

G) Keeping Track of Things – A Brief Look at Partnership

Accounting (p. 315)

1) Income Statement and Balance Sheet:

2) Capital Account

: UPA §18 (RUPA §401) states that each partner is deemed to have an account” that is credited with the net amount of the contribution and share of profits of the partner and charged with distributions to and the share of losses of the partner. This is extremely important for Federal Tax.

CheckBox1

June 28, 1999 Class (pp. 316-364)

Partner

RUPA §306

Partner

Partnership

UPA

§13,14, 9

3 rd parties

RUPA §305

RUPA §301

UPA 18-23

RUPA Article 4

Care

(c)

§21

§404

Loyalty

(b)(1)(2)(3)

H) Rights and Duties Among Partners

(p. 316) UPA §18 (RUPA

ARTICLE 4-

§401 also look to §103 (parties can agree to whatever they want- Article 4 are default rules)

1) Fiduciary Duties a) The Duty of Loyalty

(i) Duty during formation of partnership (p. 316)

Corley v. Ott (p. 316) The basic problem is that Corley was not informed that Ott had transferred the property to a strawman before Corley and Ott were going to purchase the property and purported to buy the rest of the property to the partnership. This was a breach of fiduciary duty by Ott. UPA §21 says that a partner must account to the partnership for any benefit from any transaction connected with the formation of the partnership and

RUPA §404

the only duties of a partner are the duty of care and the duty of loyalty.

(ii) Pre-empting business opportunities (p. 318)

Meinhard v. Salmon (p. 318): Meinhard gave Salmon money to lease a long term lease on a building and to reconstruct it to lease for business. They formed a 20 year lease, of which Salmon was to manage the property. Salmon was