FIELD AND HEDGEROW

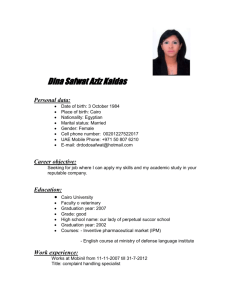

advertisement