Linguistic and Historical Continuities of the Tai Dam and

advertisement

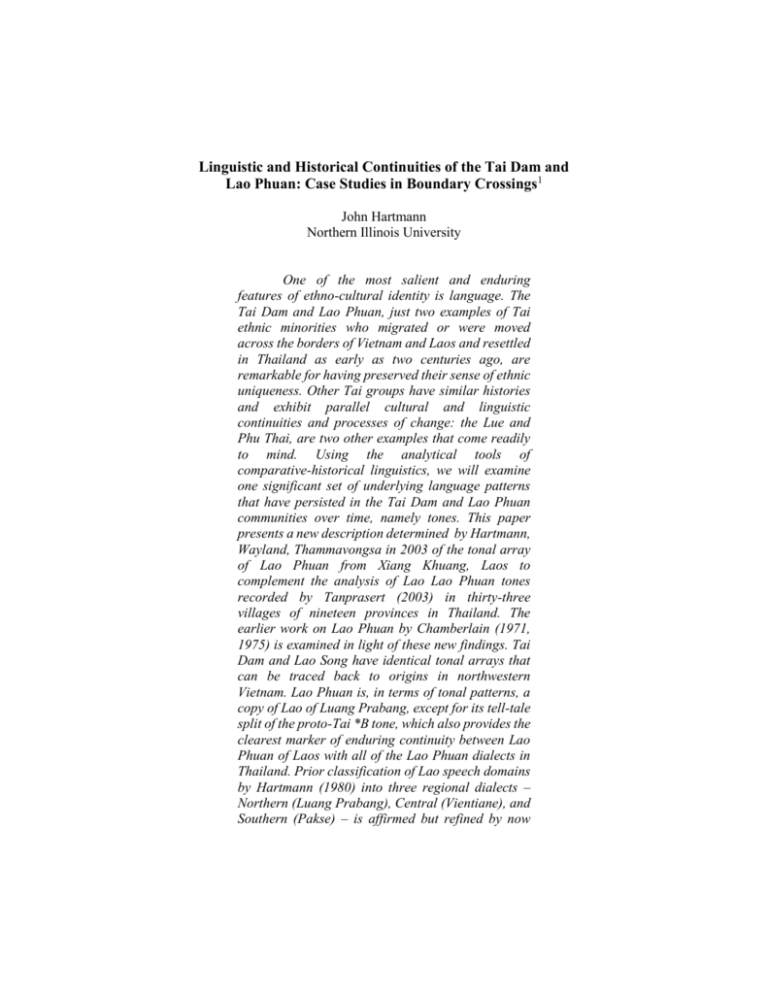

Linguistic and Historical Continuities of the Tai Dam and Lao Phuan: Case Studies in Boundary Crossings1 John Hartmann Northern Illinois University One of the most salient and enduring features of ethno-cultural identity is language. The Tai Dam and Lao Phuan, just two examples of Tai ethnic minorities who migrated or were moved across the borders of Vietnam and Laos and resettled in Thailand as early as two centuries ago, are remarkable for having preserved their sense of ethnic uniqueness. Other Tai groups have similar histories and exhibit parallel cultural and linguistic continuities and processes of change: the Lue and Phu Thai, are two other examples that come readily to mind. Using the analytical tools of comparative-historical linguistics, we will examine one significant set of underlying language patterns that have persisted in the Tai Dam and Lao Phuan communities over time, namely tones. This paper presents a new description determined by Hartmann, Wayland, Thammavongsa in 2003 of the tonal array of Lao Phuan from Xiang Khuang, Laos to complement the analysis of Lao Lao Phuan tones recorded by Tanprasert (2003) in thirty-three villages of nineteen provinces in Thailand. The earlier work on Lao Phuan by Chamberlain (1971, 1975) is examined in light of these new findings. Tai Dam and Lao Song have identical tonal arrays that can be traced back to origins in northwestern Vietnam. Lao Phuan is, in terms of tonal patterns, a copy of Lao of Luang Prabang, except for its tell-tale split of the proto-Tai *B tone, which also provides the clearest marker of enduring continuity between Lao Phuan of Laos with all of the Lao Phuan dialects in Thailand. Prior classification of Lao speech domains by Hartmann (1980) into three regional dialects – Northern (Luang Prabang), Central (Vientiane), and Southern (Pakse) – is affirmed but refined by now calling them “Mekong Lao,” a notion borrowed from Crisfield (p.c.) as my means of drawing attention to the uniqueness of “non-Mekong” Lao Phuan. A cursory summary of some of the historical events and sociological factors that lend to the persistence of the language and culture of these two ethnic Tai groups will be presented. Their “tribal labels” are political constructs that refer back to historical states that no longer exist. Still, the preservation of underlying tonal patterns unique to both groups provides an interesting “linguistic DNA sample,” showing the continuity of language and culture across national boundaries and two centuries of Thai, Tai Dam, and Phuan history. In this paper we shall begin by examining the tone systems of two different Tai groups in Thailand whose origins are from outside the political boundaries of the modern Thai state: the Tai Dam and the Lao Phuan. The Tai Dam are confined to a smaller area within Thailand than are the Lao Phuan. Lao Phuan dispersal throughout Thailand is quite remarkable for the multiple routes taken by Phuan groups entering in different waves and settling at numerous geographic points within the kingdom. A recent Ph.D. dissertation on Phuan dialects in Thailand, has provided two fine maps reproduced on the following pages showing the present settlement patterns of the Phuan in Thailand and the history of their migration into Thailand (Tanprasert 2003:5,10).2 In his classic study, Linguistic Diversity and National Unity: Language Ecology in Thailand, Smalley (1994:183) asserts a basic principle that serves as a way of looking at language similarities and differences in the Tai language family,3 namely: “tones are crucial to the ways in which Thai people identify language and dialect differences.” The number of tones and their patterning in any one Tai language or dialect is, in fact, one of the tried and true linguistic methods for grouping or classifying Tai speech groups and reconstructing part of their language histories from a parent or proto language. In effect, tonal arrays can be seen as a kind of genetic trail, a display of linguistic DNA, to borrow a metaphor from biology. Figure 1 Figure 2 The tone patterns for any Tai language or dialect can be studied by recording the speech of a native speaker using a word list that was developed by William J. Gedney (1964) over a period of several years during the course of fieldwork on over a hundred Tai dialects belonging to every branch of the family. Proto-Tai Tones4 *A *B *C *D-short/long vowels Initials (at time of tonal splits) Voiceless friction sounds, 1 5 9 13 17 *s, hm, ph, etc. Voiceless unaspirated stops, *p, etc. 2 6 10 14 18 Glottal, *?, ?b, etc. 3 7 11 15 19 Voiced, * m, j, z, n, etc. 4 8 12 16 20 Smooth Syllables Checked Syllables Figure 3. Chart Showing the Splitting of Three Proto-Tai Tones Conditioned by the Nature of Syllable-Initial Sounds Tai Dam Tonal History From Figure 4 below, we can see that the historical development of Tai Dam tones is straightforward: a simple two-way split between the original proto-Tai voiceless and voiced initials. The original three proto-Tai tones *A, *B, *C were bifurcated into six modern tones. The three tones on smooth syllables found in the upper row can be traced back to syllable-initial consonant sounds in the parent language that were voiceless; the three tones on smooth syllables in the bottom row developed from syllable-initial consonants in the parent language from voiced initials that were voiced. The homeland of the Tai Dam is in today’s northwestern Vietnam, centering around Muang Thaeng, which is more commonly known to outsiders as Dienbienphu. Tai Dam have since dispersed to points in southern China, Laos, and Thailand. Most of the descendents of the Tai Dam in Thailand are called “Lao Song Dam” (literally, “Lao Wearing Black Trousers”). In addition to what is known from historical records, we know that the Tai Dam and the Lao Song groups in Thailand are part of the same common ethnic group because of the indelible imprint of the same six-tone array in all of the dialects that have descended from the parent Tai Dam language whose origins are in today’s northwestern Vietnam. *Smooth syllables end in a vowel or -m, -n, -Ng, -w, -f, -y. **Checked syllables end in a final -p, -t, -k, or -? (glottal) sound. Figure 4. Tai Dam Tones (Hartmann 2003, after Gedney 1964. See also Theraphan 2003) A History of Mekong Lao Tones In my recent work on Lao tones carried out as part of the project for creating a website for disseminating information about Lao language and culture (www.seasite.niu.edu/lao), I combed the published literature for linguistic descriptions of Lao that date back to the 1960s. From that information, I summarized the descriptions of Lao tones in graphic form to make it easier to visualize the development of tone differences from a geographical perspective, north-to-south. Published data on the three “Mekong Lao”5 dialects was relatively easy to find. However the descriptions varied and, in the case of Central Lao spoken at Vientiane, there were two competing analyses: five vs. six tones. To satisfy myself and to be sure that the information on the Lao website was correct, I recorded the speech of two native speakers in Vientiane in August of 2002. My research confirmed the descriptions of Crisfield (2002, p.c.) and Enfeld (2002, p.c.). The following charts show the tones of Mekong Lao: Northern, Central and Southern dialects. Figure 5. Luang Prabang (Brown 1965) Northern Lao (5 Tones) Figure 6. Lao Vientiane Tones (Crisfield & Hartmann 2002/Enfield 2000) Central Lao (Five Tones) Figure 7. Pakse (Yuphaphann Hoonchamlong 1981) Southern Lao (6 Tones) What is interesting about the three regional Lao Mekong dialects is the commonality of a single, un-split tone in the proto-Tai B column (pink color), the column marked by the first tone mark (mai ek) in the writing system. The second common patterning is the split in the proto-Tai C column between the High (blue color) and the combined Mid and Low Class (yellow color) of initials. The third shared pattern is found in the DS (dead or check syllables with short vowels) column, where the split is between the combined High and Mid initials vs. the Low. The sharing of three patterns of tonal splits out of five is a strong indication of a close linguistic and historical connection between these three regional dialects. A History of Lao Phuan Tones Missing in the published literature is a solid description of Lao Phuan spoken in the Lao Phuan area centering around Xieng Khuang.6 In the spring of 2003, I asked Vinya Sysamouth if he could locate a speaker in the Lao community in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and record that person using the Gedney 20-word checklist. His father succeeded in locating a Lao Phuan woman who had been airlifted from her birthplace in Xieng Khuang during the war in Laos and evacuated to a refugee resettlement area near Vientiane. From there she eventually found her way to the U.S. as a refugee.7 Vinya e-mailed the recording to me at Northern Illinois University, and I and Kip Thammavongsa, a Lao-American born in Vientiane, analyzed the tone shapes and produced the chart below. We were not absolutely sure if our hearing produced the correct description of the unusual contour of the “High-Mid Rising-Falling” tone shown in the two white boxes below. I subsequently e-mailed the data to Dr. Ratree Wayland at the University of Florida, who did an instrumental analysis to confirm our impressionistic description. For the time being, we are in agreement on the preliminary results, but will later refine the instrumental study by using more data. Lao Phuan is not a true “Mekong Lao” dialect, but a kind of Lao nevertheless. It maintains the tonal splits of the three Mekong – i.e. Northern, Central, and Southern – dialects in two out of three patterns: column C and column DS divide along the same lines. What makes it a very atypical Lao dialect is the two-way splitting of the B column along the simple lines of proto-Tai voiceless vs. voiced initials, which, as we have seen, is what Tai Dam does across the entire line of proto tones A, B, and C. This is the singular feature of Lao Phuan that separates it from other dialects, both Lao and Tai Dam, and links it to nearly all of the myriad Lao Phuan dialects spoken in Thailand today that have been described in the work of Tanprasert (supra). In her study, all eight tonal patterns for Lao Phuan dialects spoken in Thailand show the same split in the B column. (See Addendum: Chart of Eight Tonal Pattterns of Lao Phuan Dialects in Thailand.) Figure 8. Lao Phuan Tones (Hartmann, Thammavongsa & Wayland 2003) This unique tonal split of the B column is the Lao Phuan “linguistic DNA” so-to-speak, a kind of “Mongolian green spot” that crossed the border into Thailand two centuries ago and persists to this day. A Very Short, Preliminary History of Lao Phuan and the Tai Dam The historical sketch presented by Tanprasert (supra: 2-4), relying as it does on the work of Thai historians is woefully inadequate, revisionist, and nationalistic. I have turned to the works of non-Thai scholars instead in trying to piece together a more believable, albeit incomplete, history of these two groups over the past few centuries. In his work, A History of Laos, Martin Stuart-Fox (1997:11) notes, “The Phuan Principality of Xiang Khuang on the Plain of Jars and the Sispong Chu Tai to the northeast, as well as the Sispong Phan Na to the northwest, were contested areas which at various times paid tribute to more than one of the powerful mandalas that sought to dominate them.” This places the Phuan historical origins at the exact spot that we identified in the study of Lao Phuan tones in the preceding section, namely at Xieng Khuang. As was the case with many other meuang, the Lao Phuan chiefs or chau could, as far back as the 1830s, exact tribute from upland groups living in the hills around them, such as the Hmong, Mien, and Khammu (Martin Stuart-Fox, supra, p.14). The same was true of the Tai Dam chiefs. The Phuan and Tai Dam princes, in turn, paid tribute to larger meuang in Laos, China, Siam, and Vietnam at different periods in their known history. Vientiane exercised suzerainty over the Phuan of Xiang Khuang during the Siamese ascendancy in the region. Likewise, the Tai Dam were at times in a close tributary relationship with the chiefs of Luang Prabang. It is nearly commonplace knowledge that the early Tai meuang were often at war with each other and neighboring states over control of populations and populated areas, not land itself. One of the instruments of exercising power and for securing borders was a deliberate policy of “depopulation,” moving conquered peoples out of and away from contested areas, creating a depopulated wasteland. It was a kind of pre-emptive war—a raid or pillaging, really—in reverse: invading and removing the coveted manpower before the competition could assemble its troops. The Siamese, starting in the late Thonburi-early Bangkok period were especially fond of this strategy for gaining and maintaining ascendancy, especially in Laos and northwestern Vietnam. The forced settlement of Tai Dam, Lao Phuan, and other Tai Lao groups in Thailand was the result of military campaigns that were begun toward the end of the reign of King Taksin of Thonburi and the beginning of the Chakri dynasty and continued through the reign of King Chulalongkorn. In 1778, Taksin sent his general, Somdet Chao Phraya Mahakasatseuk (who succeed him and founded the Chakri dynasty) with an army of 20,000 against Vientiane over an act of rebellion. Three years later, the Siamese were “engaged” with Luang Prabang and occupied the Tai Dam meuang of Muoi and Than. As a result of that campaign, a group of Tai Dam families were taken prisoner along with other Lao Tai. All were marched south to settlements in what are now the provinces of Saraburi, Ratburi, and Chantaburi in Central Thailand. Twelve years later, the Siamese governor of Vientianne ordered troops into Meuang Thaeng, the Tai Dam center of Sipsong Chao Tai, and Muang Phuan to quell a rebellion. This event was followed by the forced removal of populations; Tai Dam were relocated to Phetburi at this time. (Burusaphat, supra). In the violent campaign to capture the rebellious Chao Anuwongse of Chamapasak during the reign of Rama III, Siamese armies set fire and laid waste to most of Vientiane in 1829 and again moved into Meuang Thaeng. More Tai Dam were taken prisoner then and similarly moved to Phetburi province, which had become a kind of reservation, intentionally isolated from contact with the Siamese in Central Thailand. In 1836, following a rebellion of three Tai Dam meuang, even more Tai Dam captives were removed to Phetburi. Uprisings in Sipsong Chao Tai resulted in enslavement of more Tai in 1838, 1864, and other points in time during the last half of the nineteenth century (Burusaphat, supra). According to Vella (1957:787), an estimated 46,000 inhabitants of these frontier and foreign regions were taken captive and enslaved in Thailand. Under orders from Prince Damrong, between 1885 and 1889, Tai Dam and other Lao Tai were removed from depopulated areas and resettled in Thailand, even though King Chulalongkorn had decreed freedom for native-born slaves and descendents of prisoners of war when he ascended the throne in 1868. Enslavement and Encapsulation: Effect on Linguistic and Cultural Preservation The Tai Dam comprised the largest population of the total displaced upland Tai resettled in Thailand. Following a policy of strategic resettlement, they were exploited as a line of military defense to the west of Bangkok, among other dimensions of enslavement. They were conscripted to drain swamps, clear savannah, dig canals, and construct buildings such as the royal complex atop Khao Wang in Bangkok. All the while they were kept physically isolated from the Siamese majority as part of a deliberate policy mandated by the government. Compounding this socio-political segregation was the distinctiveness-cum-separateness of Lao Song-Tai Dam culture. As the label indicates, they stood apart because of the black garments they wore. Their patrilineal kinship system further mitigated against their intermarrying with the Siamese. Moreover, they were not Buddhists, as were the majority Siamese. The Siamese government thus was unwittingly complicit in the preservation of Lao Song kinship communities. Like most ghettoized peoples everywhere, cultural and linguistic distinctiveness emerges and assumes an identificational aspect. This was especially true of the Lao Song/Tai Dam up until the recent past. However, with the construction of roads into Lao Song areas, the introduction of compulsory education, the assimilationist policies of the Thai government, and the forces of globalization, the drift towards Standard Thai speech and Bangkok-dominant culture is unstoppable. The case of the Lao Phuan seems to be different in some aspects. At this point in my reading and research, I do not have enough information to do much more than to comment on language issues. Tanprasert’s (supra) linguistic research on the Phuan of Thailand indicates that their language and culture has been largely preserved among the group of women aged 45 and older who were born in the village where the linguistic interview took place, had never moved, and had no more than 4 years of schooling. The influence of Central Thai on Phuan speech had thus been minimized. If anything, they had been influenced by the more immediate effects of contact with the speech of neighboring dialects, e.g., Lanna, Isan. The younger generation, however, has received much more schooling, where the influence of Central Thai is immediate and strong. Tanprasert reports that the children do not like to speak Phuan with peers and adults alike. Unlike the Tai Dam, Phuan everyday dress is not all that identificational, and they are Buddhist and participate in Buddhist rituals. Intuition tells me that their kinship ideology is not patrilineal and that they freely intermarry with the Thai as a consequence. Judging from the fact of their wide dispersal over nineteen provinces of Thailand, it appears that the Central Thai authority did not apply the same rules of restrictive and isolated residence to the Lao Phuan that they did with the Tai Dam. One is safe in predicting that the Lao Phuan will complete their assimilation to one of the regional Thai dialects and cultures at a faster rate than the Lao Song-Tai Dam. In a later stage, their absorption into the Thai mainstream culture again will come closer to completion than the Tai Dam, who have historically invested a great deal of political capital in standing apart from and often in opposition to outside powers. Notes 1. I would like to thank Carol Compton for helping to improve and clarify the paper in numerous ways. Any errors that might still appear in the final version are my own responsibility. Kip Thammavongsa's assistance in editing the paper and preparing it for Web delivery was invaluable. Ratree Wayland's instrumental analysis of Lao Phuan tones from the Lao data gave me the confidence I needed to complete this project. Without Vinya Saysamouth's help in recording the original Lao Phuan speech files, the paper would not have been written in the first place. Professor Somsonge Burusaphat's invitation to me to be on Pornpen Tanprasert's doctoral committee provided the original catalyst. I am grateful to both for the honor. Arthur Crisfield has assisted me mightily from Laos for the past several years, providing wonderful insights and inspiration. This paper has numerous mothers and fathers: I am very grateful to all for their assistance. 2. I served as an outside, foreign member of her committee. Hence my intimate knowledge and appreciation of her work. 3. The Tai language family is divided into three branches: Northern (Tai languages found mainly in Guangxi and Guizhou provinces in China); Central (Tai language spoken in border are as between northern Vietnam and southern Guangxi); Southwestern (Tai languages spoken in parts of northwestern Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, the Shan State in Burma, and Assam, India (where they actually died out several generations ago). See the "Map of the Tai Language Family" in the Addendum. Thai is the official language of Thailand. Siamese or Central Thai is sometimes synonymous with Thai. 4. Only tones on smooth syllables are treated as phonemic. Tones on checked syllables are allotones of tonemes on smooth syllables because they are conditioned by syllable type. 5. This is a term and perspective that I picked up from Arthur Crisfield in an e-mail message in 2003. 6. The exception is Chamberlain 1971, where he lists 6 tones: low-rising; mid-level; low-level; low rising-falling; high-falling; and high-rising. The splits are: A 123-4; B 123-4; C 123-4; DL 123-4; DS 123-4. The pattern is the same as the simple 2-way splitting of Tai Dam, which makes his description suspect. 7. In the process of recording her tones, Vinya got her to produce an oral history of her life centering around the evacuation. This recorded interview and her pronunciation of Phuan-Xieng Khuang tones can be listened to at www.seasite.niu.edu/lao. The tones are found by clicking on "Language," and the interview under "Others." References Burusaphat, Somsonge 1983. Prawat Lae Khwaam Pen Maa Khong Lao Song [History and Origins of the Lao Phuan]. Saan Phu Thai [Phu Thai Journal], special issue. pp. 5-14. Brown, J. Marvin 1965. From Ancient Thai to Modern Dialects. Bangkok: Social Science Association Press of Thailand. Chamberlain, J. R. 1971. A Workbook in Comparative and Historical Tai Linguistics. Bangkok: English Language Center of the University Development Commission. _______.1975. A New Look at the History and Classification of the Tai Languages. Studies in Tai Linguistics in Honor of William J. Gedney. Edited by Jimmy G. Harris and James R. Chamberlain. Bangkok: CIEL. Gedney, W. J. 1964. A Comparative Sketch of White, Black, and Red Tai. Social Science Review, special publication I. Bangkok. Hartmann, J. F. 2003. Lao Vientiane Tones. Available from World Wide Web @ http://www.seasite.niu.edu/lao/tones Hartmann, J. F., K. Thammavongsa, and R. Wayland. 2003. Lao Phuan Tones. Available from World Wide Web @ http://www.seasite.niu.edu/lao/tones Hartmann, J. F. 1980. A Model for the Alignment of Dialects in Southwestern Tai. Journal of the Siam Society 68.1. pp. 72-86. Pornpen Tanprasert. 2003. A Language Classification of Phuan in Thailand: A Study of the Tonal System. Ph.D. dissertation. Mahidol University. Smalley. W. A. 1994. Linguistic Diversity and National Unity: Language Ecology in Thailand. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Stuart-Fox, M. 1997. A History of Laos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Theraphan L-Thongkum. 2003. The Tai of Muong Vat Do Not Speak the Tai Language. Manusya Special Issue No. 6. pp. 74-86. Vella, W. F. 1957. Siam Under Rama III, 1824-1851. New York: Augustin Inc., Publishing. Yupphaphan Hoonchamlong. 1981. Lao Pakse Tones. Available from World Wide Web @ http://www.seasite.niu.edu/lao/tones Addendum Figure 9. Map of the Tai Language Family Showing the Three Branches: Northern (Chartreuse); Central (Blue); Southwestern (Aqua) Figure 10. Chart of Eight Tonal Patterns of Lao Phuan Dialects in Thailand (Source: Tanprasert 2003, p. 135)