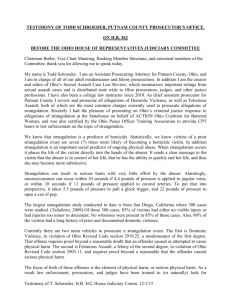

Introduction - Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse

advertisement