Extended Abstract

advertisement

New Product Entry: the Moderating Role of Compromise Effect on Pioneering Advantage

1

ABSTRACT:

Consumer research has mainly focused on the static nature of the compromise effect without

considering how time varying factors may influence decision rules and the composition of choice

set. New products entry and the position occupied by new brands modify the context of choice and

consequently can change preferences.

This article examines the extend to which order of entry affects the robustness of compromise

effect. Our results demonstrate that a pioneer brand could be negatively or positively affected by the

arrival of a new alternative when this turns it into an extreme or a compromise alternative.

2

Extended Abstract:

The reader will be familiar with the rich literature within marketing, economics, and strategy

regarding order of entry effects. The general proposition emanating from research in economics is

that first movers will have lasting advantages (Bain 1956; Bond and Lean 1977; Schmalensee

1982). This has been confirmed in a number of marketing studies (Robinson and Fornell 1985;

Urban et al. 1986; Robinson 1988b), and the mechanisms whereby pioneer advantage is derived

have been explored. However, results are not unequivocable (Moore, Boulding, and Goodstein

1991). In particular, it has been argued that first movers tend to have higher returns but their order

of entry is also related to higher risk of failure (Kalyanaram and Urban 1992). Indeed, research on

first mover advantages has been shown to be subject to a number of limitations and potential biases

(Kerin, Varadarajan, and Peterson 1992).

An important stream of literature on pioneering advantage is interested in explaining pioneering

advantage from a behavioral perspective. In particular Carpenter and Nakamoto (1989) and Kardes

and Kalyanaram (1992) have explored the cognitive mechanism underlying this phenomenon,

indicating that a consistent portion of pioneering advantage can be ascribed to cognitive

mechanisms. In particular, Carpenter and Nakamoto (1989) suggest that pioneering advantage is the

outcome of the consumers’ learning process as well as preference formation. More recently,

literature in marketing and consumer behavior has questioned the robustness of order of entry effect

consequently the existence of the follower advantage has been explored.

The entry of new brands determines the rise of not only an order, but also a context effect. A

new brand might dominate or being dominated by the first and the second brands, therefore being

an extreme option, or become an intermediate option. Interestingly, extant literature has shown that

brands can gain share when they become intermediate options in the choice set. This phenomenon

has been widely researched and it is known as compromise effect (Chernev 2004; Dhar and

Simonson 2003; Novemsky and et al. 2004; Nowlis and Simonson 2000; Sheng, Parker, and

Nakamoto 2005; Simonson 1989).

While investigating compromise effect, consumer research literature tends to focus on its static

nature without considering how time varying factors may influence decision rules and the

composition of choice set. Several factors might affect the composition of choice set and those

factors could be the outcome of diffusion effect or the result of firms’ conduct. For instance, the

increasing availability of information over time and the arrival of a new brand in a market might

affect the consumers’ preference formation process and might determine a modification of the

context within which choices are made.

Our work intends to marry these two streams of literature by examining the impact of context

effects (i.e. compromise effect) on order effects (i.e. pioneering advantage). In particular we are

interested in understanding how the position that the pioneer occupies into the choice set, after the

arrival of followers, can change the intensity of its alleged advantage.

It should be noticed that, while studying compromise effect in a dynamic context one should

take into consideration the evolution of consumers’ preferences and the increase in their knowledge

about product categories. In particular, familiarity with a product category could also influence the

impact of compromise on order of entry effects. This study also aims to understand whether highly

familiar consumers tend to ascribe lesser value to pioneering status when a brand acquires an

extreme or compromise position in a choice set as a consequence of a follower arrival.

In our empirical investigation, we use a within-subject design whereby subjects undertook a two

part task. Participants in the experiment were 165 students at a major European University and the

experiment is a 2 (set size: two vs. three product alternatives) Χ 3 (information on the pioneer:

extreme alternative as the pioneer vs. compromise alternative as pioneer vs. no information on the

order of market entry) factorial design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the

3

experimental conditions. With a time lag of five days participants were asked twice to carry out the

same task.

The sample was divided in three groups to control for factors external to the experiment. Group

1 examined the case in which the extreme alternative A was the pioneer, while Group 2 examined

the case in which the middle alternative B was the pioneer: both groups were told that alternative C

was the third entrant into the market. Group 3 served as control group with participants being given

no entry order information.

Our results show the presence of compromise effect in the absence of information about order

of entry and different pattern of choice in presence of such information.

The compromise effect was not significant when the first brand entering the market was the middle

option B because that option was the most chosen already at time t1: the pioneer could hold its

advantage if the followers chose a position that identifies the pioneer as the middle option. When

the first brand turned out to be an extreme option (A) after the arrival of followers, the composition

of the new choice set would favor the rise of compromise effect: the presence of the information on

the pioneering status of option A would increase the share of option A but would not vanish the

compromise effect.

Additionally, we observed a significant difference between the strength of the compromise

effect when brand B was the pioneer and when no pioneer information was provided (respectively,

t-test = 4.42 and t-test = 3.30). On the contrary, in both the product categories examined, there we

did not find a significant difference between the case in which A was the pioneer and when no

additional information was provided. More importantly, we show that the magnitude of compromise

effect changed in magnitude when A or B were the pioneer.

Finally, by dividing respondents by their degree of product category familiarity, we could

identify two groups: low familiar consumers and high familiar consumers. The analysis of choices

for both high and low levels of familiarity shows interesting results. More specifically, familiarity

affects the relationship between order and compromise effects. In particular, for high levels of

familiarity our results do not differ from those obtained while considering the entire sample; By

contrast, for low levels of familiarity, the pioneer brand holds the preferences even when the arrival

of followers creates condition for the rise of compromise effect. This suggests that low familiarity

acts upon consumers preferences uncertainty and serves as driver for the use of the easier and more

explicit cue, which in our case is related to the pioneering status. When familiarity increases, the

more available cue (i.e. order of entry) does not serve as principal preference driver, and the pioneer

advantage is overcome by the composition of choice set.

4

New Product Entry: the Moderating Role of Compromise Effect on Pioneering Advantage

INTRODUCTION

The compromise effect, which predicts that brands can gain share when they become intermediate

options within the choice set, is one of the strongest and most important effects documented in

behavioral decision research, systematically affecting choice under different conditions (Chernev

2004; Dhar and Simonson 2003; Novemsky and et al. 2004; Nowlis and Simonson 2000; Sheng,

Parker, and Nakamoto 2005; Simonson 1989). Most research on choice focuses on the decision

rules by which consumers select an option from amongst a set of alternatives, as if both choices and

alternatives were completely independent of any other choice. This implies that choices are

analyzed as ‘one shot’, time-invariant events. Obviously this approach disregards several factors,

such as correlation among choices (i.e., sequence of non independent decisions); the dynamic nature

of information availability and time-dependent relationships between alternatives within choice

sets.

Relationships between alternatives may or may not be driven by firms’ actions. For instance, the

actual order in which products enter the marketplace is the result of firms’ conduct, whereas

customers’ increasing knowledge of this market entry order, and their familiarity with product

categories are the outcome of diffusion effects. Both conditions, however, might affect the

consumers’ preference formation process. Interestingly the arrival of a new brand in a market also

determines a modification of the context within which choices are made. In particular, a pioneer

brand could be negatively or positively affected if the arrival of a new alternative turns it into either

an extreme or a compromise alternative (Lehman and Pan 1994). Moreover, when product

familiarity acts on uncertainty and preference constructions, it can moderate the interaction between

the order of entry and the compromise effect in affecting purchasers’ decisions.

5

Our work examines the interaction between these two effects as well as the moderating role

played by product category familiarity. Our findings contribute to extant research in various ways:

i) by identifying conditions that might enhance or attenuate pioneering advantage; ii) by showing

whether and how the compromise effect is modified by time varying conditions; iii) by analyzing

the effect of product category familiarity on the use of information and heuristics.

1. RELEVANT LITERATURE

The present study focuses on the evolution of context effects, and in particular the compromise

effect, hypothesizing an array of choices repeated in a time period during which the consumer is

exposed to the arrival of new brands onto the market.

More specifically, the object of this research is to examine the interaction between preferences

related to the pioneer option and those related to the compromise option. We aim to understand how

repeated exposure to choice sets that might favor the emergence of compromise effect interact with

information about the order of entry of alternatives into the choice set, distinguishing the cases in

which the pioneer brand occupies the extreme position in the choice set from that where it

represents the ‘middle’ (i.e. ‘compromise’) position.

1.1 Compromise effect and Pioneering advantage

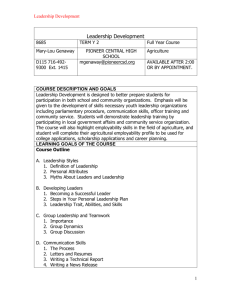

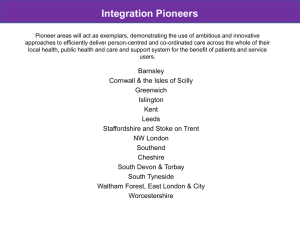

Among context effects, the compromise effect has recently received increasing attention (Chernev

2004; Dhar and Simonson 2003; Dhar, Menon, and Maach 2004; Kivetz, Netzer, and Srinivasan

2004; Novemsky et al. 2004; Parker and Nakamoto 2005; Sheng et al. 2005). Empirically observed

by Simonson (1989), this effect denotes the phenomenon by which a brand’s market share is

enhanced when it occupies an intermediate position in the choice set. In particular, the compromise

effect occurs if the choice share of option B, relative to option A, is enhanced when a third option C

is added to the choice set, making B the ‘compromise’ option (see Figure1).

6

FIGURE 1: COMPROMISE EFFECT

Attribute y

y1

A

B

y2

C

y3

x1

x2

x3

Attribute x

Prior research into context effects (Benartzi and Thaler 2002; Chernev 2004; Dhar, Nowlis, and

Sherman 2000; Drolet 2002; Huber, Payne, and Puto 1982; Nowlis and Simonson 2000; Simonson

1989) has attempted primarily to document the existence of these phenomena as ‘one-shot’ choice

events. Although more recently attention has focused on subsequent choices (Amir and Levav 2006;

Drolet 2002), limited effort has been made to investigate whether and how the compromise effect is

influenced by external time-varying conditions.

Our main hypothesis is that the interaction between the compromise effect and pioneer

advantage is moderated by the nature of the pioneer alternative. In particular, we contend that

information about the pioneer can drive preferences, allowing it to gain share when information is

available as compared to when it is not.

The reader will be familiar with the rich marketing, economics and strategy literature regarding

order of entry effects. The general, the proposition emanating from research in economics is that

first movers will have lasting advantages (Bain 1956; Bond and Lean 1977; Schmalensee 1982).

This has been confirmed in a number of marketing studies (Robinson and Fornell 1985; Urban et al.

1986; Robinson 1988b), and the mechanisms whereby pioneer advantage is derived have been

7

explored. However, results are not altogether unequivocal (Moore, Boulding, and Goodstein 1991).

In particular, it has been argued that while first movers tend to have higher returns, they also run

higher risks of failure (Kalyanaram and Urban 1992). Indeed, research on first mover advantages

has been shown to be subject to a number of limitations and potential biases (Kerin, Varadarajan,

and Peterson 1992).

An important stream of literature on the pioneer advantage is interested in explaining order of

entry from a behavioral perspective. In particular Carpenter and Nakamoto (1989) and Kardes and

Kalyanaram (1992) have explored this phenomenon, indicating that a consistent part of pioneer

advantage can be ascribed to cognitive mechanisms. In particular, Carpenter and Nakamoto (1989)

suggest that pioneer advantage is the outcome of consumers’ learning and preference formation

processes.

More recently, marketing and consumer behavior literature has questioned the robustness of the

order of entry effect, and has consequently explored the existence of a follower advantage. On one

hand, it is widely recognized that first movers tend to become the category standard for consumers,

and later entrants risk being be evaluated merely as imitations of the pioneer (Carpenter and

Nakamoto 1988). On the other hand, later entrants have been shown to enjoy, on average,

advantages both in cost terms (Boulding and Christen 2001) and in terms of the stage of their

products’ life cycles (Shankar, Carpenter, and Krishnamurthi 1999).

Heuristics such as compromise effects are often used to facilitate the choice process: Dhar and

Simonson (2003) have shown that options are sometimes selected, not because they are preferred,

but because they allow customers to resolve difficult purchasing decisions by choosing the

alternative in the ‘middle’ of a market as a compromise choice (Simonson 1989). Our main

proposition is that consumer preference for pioneer brands can also simplify their choice process, in

this case towards the product that entered the market first. This will depend, of course, on

information about market entry order being available, and where it is, it will tend to undermine the

8

conditions which sustain the compromise effect. In such cases, the pioneer effect may weaken, or

even cancel out, the compromise effect.

In the situation when a new brand C joins the market previously composed of brands A and B, we

expect that, where the pioneer brand becomes the middle option B, the order of entry effect will

outweigh the compromise effect. On the other hand, when the pioneer brand occupies the extreme

position A, the compromise effect will not be diminished, as the middle option (B) will still benefit

from being the ‘easy’ choice for uncertain customers.

H1: When option C is included in the choice set, if the compromise alternative B is the

pioneering brand, its share increases, but influence of the compromise effect is diminished

H2: When option C is included in the choice set, if the extreme alternative A is the pioneering

brand, its share increases, although the compromise effect still benefits option B.

H3: When the extreme alternative C is included in the choice set, the compromise effect is

stronger when the pioneering brand is in the extreme position (A) than when it is in the

compromise position (B).

1.3 Product Category Familiarity

Previous literature has used the terms familiarity, expertise, and experience interchangeably to

refer to prior knowledge (Sheng et al. 2005). Alba and Hutchinson (1987) categorized consumer

knowledge as two major components: familiarity, defined as the number of product-related

experiences previously accumulated by the consumer, and expertise, defined as the ability to

perform product-related tasks successfully.

Consumers usually bring their prior knowledge to influence the choice process (Bettman,

Johnson, and Payne 1990). In terms of context effects, it is widely recognized that perceived

knowledge and expertise play a central role in understanding the choice process. Product familiarity

can influence product evaluations, information processes and choices (Alba and Hutchinson 1987;

9

Johnson and Russo 1984). Interest in the impact of product familiarity on choice has recently been

coupled with the study of the influence of familiarity on context heuristics. In particular, Sheng et

al. (2005) have studied the effect of product familiarity on the compromise effect, showing that

highly familiar consumers are less prone to adopt the compromise heuristic in making their choices.

In case of context effects, product familiarity may influence choices both by acting on the

information acquisition process, facilitating the attainment of new information, and on the

development of evaluations and choice rules that facilitate the growth of preferences. A consumer

who is very familiar with the product category can generate a more complete evaluation of the

category’s products, and is thus more likely to make a decision based on his own preferences:

consequently, as shown by Sheng et al. (2005), a highly familiar consumer is less likely to be

influenced by heuristics, particularly the compromise effect.

At the same time, different authors have proposed alternative recommendations to use product

category familiarity to overcome a first entrant’s advantage. A critical assumption underlying

Carpenter and Nakamoto’s study (1989) is the novelty of the product category that the pioneer is

creating. However, pioneering advantage has also been observed in familiar product categories, and

Kardes and Kalyanaram (1992) have examined its sources in such contexts. They contend that the

repeated exposure to the pioneer brand, as well as advertising, makes it appear novel and

interesting, and therefore attention-drawing. This implies that information on the pioneer is stored

in customers’ long-term memory. A consumer repeatedly exposed to the pioneer will become more

familiar with it, and may treat information (e.g. about similar attributes) about later entrants as

redundant.

These two perspectives provide different recommendations as to what a follower should do. In

particular the former suggests that followers should pursue distinctive strategies in order to restart

the learning process, whereas the latter argues that, as consumers might not perceive the ‘newness’

of a later entrant’s brand, such a distinctive strategy would not be rewarded.

10

Similar differences in recommendations have been recently ascribed to the different levels of

product category familiarity examined (Zough and Nakamoto 2007). Since the aim of this study is

to understand the interaction between the compromise effect and pioneer advantage, our interest in

product familiarity is connected to its impact on the strength of these two effects.

Our purpose is first to understand if product familiarity can influence pioneer advantage, and

second to identify how product familiarity acts upon the interaction between the compromise and

pioneer effects. We use product familiarity as a proxy of consumers’ prior knowledge about brands

or product categories (Sheng, et al. 2005). Product category familiarity may have a role in

influencing the strength of the pioneer advantage and determining the extent of the follower

advantage. As previously noted, Carpenter and Nakamoto (1989) find that, in conditions of low

product familiarity, pioneer advantage is not diminished by the arrival of a follower where that new

entrant is not differentiated. Similarly, in conditions of high familiarity, Kardes and Kalyanaram

(1992) argue that consumers will regard information provided by a non-dominant new entrant as

redundant, and therefore the pioneer advantage is again not diminished by a follower’s arrival. As

result we contend:

H4: Product category familiarity does not influence customers’ preferences towards later

entrants

Following Sheng et al. (2005), our expectations are that the impact of the compromise effect will

have a greater modifying effect over pioneer status information where product familiarity is low,

and a lesser effect where familiarity is high. Low levels of product familiarity, associated with

higher uncertainty and less defined preferences, also favor the rise of the compromise effect,

increasing the preference for the intermediate option. By contrast, high levels of product familiarity

decrease the use of the compromise heuristic, favoring the relevance of order of entry.

11

H5a: Consumers less familiar with the product will be more influenced by the compromise

effect than by the pioneer advantage effect.

H5b: Consumers more familiar with the product will be less influenced by the compromise

effect than by the pioneer advantage effect.

3. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Participants in the experiment were 165 students at a major European University. Their instructions

were that the experimenter was only interested in their opinion and there was no right or wrong

response. The study, conducted during regular class meetings, consisted of a two-part task. The

experiment was a 2 (set size: two vs. three product alternatives) Χ 3 (information on pioneer brand:

pioneer as the extreme alternative vs. pioneer as compromise alternative vs. no information on the

order of market entry) factorial design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the

experimental conditions. Every respondent was asked to rate their product familiarity in each

product category and to make a choice between the alternatives. Participants were also told to

assume that alternatives were similar as far as all unmentioned attributes were concerned.

Participants were asked to carry out the same task twice, matched with the same experimental

conditions, with a time lag of five days between experiments (see Table 1 for a description of the

experimental conditions). At the end of the each task, participants were debriefed. In the first round

(t1) we collected data from 186 students, while in the second round (t2) the participation rate

decreased and we could only reach 168 students from the initial sample. After screening the

questionnaires the panel of respondents was reduced to 165 valid questionnaires.

The sample was divided in three groups to control for factors external to the experiment. We

presented all respondents with three products in each of two categories - digital cameras and mp3

players - using fictitious names in order to avoid any bias connected with experience of real brands.

12

In the first session all the participants saw a choice set composed of two alternatives {A;B}, while

in the second session they saw a choice set composed of three alternatives {A;B;C}, allowing us to

test for the compromise effect within subjects.

Group 1 was told that the extreme alternative A was the pioneer, while Group 2 was told that

the middle alternative B was the pioneer: both groups were told that alternative C was the third

entrant into the market (Table 1). The comparison between these groups allowed us to assess the

presence and size of the compromise effect where information about market entry order was

available. (Group 3 served as the control group, with participants being given no entry order

information.)

TABLE 1: DESCRIPTION OF EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Groups

Group 1

A is the pioneer

Time 1

Camera A,: 150€, 3m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

--------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

Camera A: 150€, 3m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

Group 2

B is the pioneer

Control Group

No information

on the order

Of entry

--------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

Camera A: 150€, 3m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

--------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

13

Time 2

Camera A: 200€, 4m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

Camera C: 350€, 7m pixel

-------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

Mp3 Player C: 199€, 4 Giga

Camera A: 200€, 4m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

Camera C: 350€, 7m pixel

-------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

Mp3 Player C: 199€, 4 Giga

Camera A: 200€, 4m pixel

Camera B: 250€, 5m pixel

Camera C: 350€, 7m pixel

-------------------------------Mp3 Player A: 80€, 1 Giga

Mp3 Player B: 140€, 2 Giga

Mp3 Player C: 199€, 4 Giga

4. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Line 3 in table 2 and 3 illustrate the presence of the compromise effect on the control group choices

for digital cameras and mp3 players when no order of entry information is made available. For both

product categories the percentage of participants choosing the middle alternative B compared to

alternative A increases when a new extreme alternative C is introduced. Thus, in the digital cameras

category, the percentage of respondents selecting B over A changes from 49% (at t1, when the

choice is between only the two brands A and B) to 78% (at t2, when the choice is between all three)

TABLE 2: CHOICE PERCENTAGES

A Pioneer

B Pioneer

No Pioneer

Digital Cameras

Time 1

Time 2

A%

B%

A%

B%

C%

74.00 26.00 42.00 50.00

8.00

25.93 74.07 18.52 70.37 11.11

50.82 49.18 18.03 65.57 16.39

Mp3 Players

Time 1

Time 2

A%

B%

A%

B%

C%

68.00 32.00 40.00 50.00 10.00

7.41

92.59 11.11 68.52 20.37

45.90 54.10 11.48 65.57 22.95

When consumers are provided with information about market entry order we can observe, as

expected, different effects depending on the position occupied by the pioneer. For digital cameras,

at T1, Group 1 saw the choice set {A;B} in which the alternative A (the extreme alternative,

characterized by low price and low performances) was the first brand that entered the market and

the option B is identified as the follower. In this case the information about the order of entry

influenced consumers’ preferences, with 74% of respondents choosing the pioneer alternative

against only 26% choosing the follower.

When the alternative C become available (at t2), we can see that preferences for the pioneer

option are mitigated by the composition of the choice set: the entry of brand C causes more loss of

share from the (extreme) brand A than from the (now) middle brand B. We can see that consumers

chose the compromise alternative even when they are provided with the explicit information about

14

the pioneering status of the alternative A. The difference in the share of option B when it is in the

set {A;B} and when it is in the set {A;B;C} is significant at 0.01% (see Tab. 3).

On the contrary, in line 2, when alternative B is the pioneer and A is the follower, consumers

continue to prefer B over A, and the appearance of the extreme alternative C at t2 does not change

this preference distribution. As we predicted, when the pioneer is the compromise option, the

magnitude of the compromise effect is reduced, being overtaken by the preference accorded to the

pioneer.

For the Mp3 players, when the alternative A is identified as the pioneer brand, the entry of

option C alters preferences more towards option A than to option B, showing the presence of a

strong compromise effect. When option B is the pioneer brand, the middle option was already the

preferred choice at t1, and the arrival of alternative C again does not change the pattern of

preferences: the middle option B is the most chosen, but the compromise effect is null.

TABLE 3: SHARE OF B OVER A

Digital cameras

Time 1

Time2

t-test

A Pioneer

.26

.54

2.84b

B Pioneer

.74

.79

.61

No Pioneer

.49

.78

3.18 a

a

significant at .05%

b

significant at .01%

Mp3 Players

Time 1

Time2

.32

.56

.93

.86

.54

.85

t-test

2.30 a

1.05

3.41b

Table 3 shows that hypothesis H1 is confirmed for both Digital cameras and Mp3 Players, because

the compromise effect is not significant when the pioneer brand is the middle option B (t-test is

respectively equal to 1.05 and 0.61). Moreover, the share of option B increases compared to the

case of there being no market entry order information: for the digital cameras, at t1, 74% of the

respondents who knew about its pioneering status choose option B, while without that information

only 49% preferred option B (t-test = 2.49, sign. .05).

15

Hypothesis H2 stated that the presence of the information on the pioneering status of option A

would increase the share of option A but will not counteract the compromise effect. In table 2 we

can find support for hypothesis 2: for Mp3 players, preferences for A goes from 45.9% (in the

absence of market entry order information) to 68% when A is known to be first brand to enter the

market (t-test = 2.33 sign. .05). The compromise effect is also significant for both product

categories.

TABLE 4: MAGNITUDE OF COMPROMISE EFFECT

A Pioneer

B Pioneer

No Pioneer

Digital Camera

Δ B (T2-T1)

.28

.05

.29

Mp3 player

Δ B (T2-T1)

.24

.07

.31

Table 4 shows the difference in the strength of the compromise effect when the pioneering brand

varies between A, B and neither of them. The differences between the share of B at time t1 and t2

(defined as: Δ B (T2-T1)) give us a measure of the compromise effect’s strength in the different

experimental conditions. For both the product categories there is a significant difference between

the strength of the compromise effect when B is the pioneer brand and when there is no pioneer

information (respectively, t-test = 4.42 and t-test = 3.30). On the contrary, again for both the

product categories, there is no significant difference when A is the pioneer compared to when there

is no market order entry information. More important, supporting hypothesis H3, there is a strong

and significant difference in the magnitude of the compromise effect depending on whether A or B

is the pioneer.

We can observe increased product familiarity from t1 to t2: exposure to the product category and the

choice increases the perceived familiarity weakly in both categories, but none of the differences are

statistically significant (see Table 5).

16

TABLE 5: FAMILIARITY

Digital Camera

Mp3 Player

Familiarity Familiarity Familiarity Familiarity

T1

T2

T1

T2

Total

4.15

4.50

4.97

5.12

A Pioneer

4.30

4.62

5.14

5.14

B Pioneer

4.02

4.37

4.98

4.96

No Pioneer

4.15

4.51

4.85

5.24

To assess the moderating role of familiarity on the relationship between the compromise and the

pioneer effects, we distinguished between low levels of familiarity (characterized by values ≤ 4)

and high levels of familiarity (characterized by values > 4) and analyzed both effects in both low

and high familiarity cases. Considering the pioneering advantage, we find confirmation for

Carpenter and Nakamoto’s (1989) and Kardes and Kalyanaram’s (1992) results (see Table 6): we

can observe a strong preference for pioneer brand over the follower for both product familiarity

levels.

TABLE 6: CHOICE PERCENTAGE FOR LOW AND HIGH FAMILIARITY

Digital Camera

Low familiarity ≤ 4

High Familiarity > 4

Time 1

Time 2

Time 1

Time 2

A% B% A% B% C% A% B% A% B%

A Pioneer .76 .24 .52 .33 .14 .70 .30 .37 .60

B Pioneer .33 .67 .32 .68 .00 .14 .86 .00 .74

No Pioneer .48 .52 .28 .66 .07 .54 .46 .09 .66

MP3 Player

Low Familiarity ≤ 4

High Familiarity > 4

Time 1

Time 2

Time 1

Time 2

A% B% A% B% C% A% B% A% B%

A Pioneer .64 .36 .53 .47 .00 .69 .31 .34 .51

B Pioneer .10 .90 .17 .78 .06 .06 .94 .09 .63

No Pioneer .58 .42 .21 .68 .11 .39 .61 .07 .64

C%

.03

.26

.25

C%

.14

.29

.29

A different choice pattern is associated with different levels of product familiarity (see Table 7):

when familiarity is low consumers prefer the pioneer brand independently of the composition of the

choice set. On the contrary, when familiarity is high, preferences are still for the pioneer brand but

only when it is the compromise option (B) (see previous results in Table 3).

17

TABLE 7: SHARE OF B OVER A FOR LOW AND HIGH FAMILIARITY

Digital Camera

Low Familiarity ≤ 4

High Familiarity > 4

% B on A Time 1 Time2 t-test Time 1 Time2 t-test

A Pioneer

.24

.39

.05

.30

.62

2.27 a

B Pioneer

.67

.68

.09

.86

1.00

1.62

No Pioneer

.52

.70

1.46

.46

.88

3.10 a

Mp3 Players

Low familiarity ≤ 4

High Familiarity > 4

% B on A Time 1 Time2 t-test Time 1 Time2 t-test

.36

.47

.60

.31

.60

2.31 a

A Pioneer

.90

.82

.68

.94

.88

.80

B Pioneer

No Pioneer

.42

.76

2.21a

.61

.90

2.67 b

a

significant at .05%

b

significant at .01%

When familiarity with product category is high, results from hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 are

replicated. We observe a strong compromise effect when the alternative A is the pioneer, no

compromise effect when option B is the pioneer and a strong compromise effect when there is no

additional information on the order of brand entry. Surprisingly, when familiarity is low, results do

not support our hypotheses H5a and H5b. In this case, option A retains its pioneer advantage through

to t2 despite the context (there are now three brands) indicating the possibility of a compromise

effect.

Our results suggest that, in case of low product category familiarity, pioneering advantage drives

preferences more strongly than compromise effect. In particular, as low familiarity is associated

with high degree of novelty and uncertainty as to their preferences, consumers appear to base their

choices more on available information (i.e., order of entry) than on the context heuristic (i.e.,

compromise effect).

18

5. CONCLUSIONS

Order of entry and compromise effects have been observed to affect the formation of

consumers’ preferences. Both can influence firms’ performance. Order of entry can lead pioneer

brands to retain greater market share than later entrants, whereas the compromise effect can lead

brands to gain share when they become the intermediate options in a choice set. This study contends

that these effects might interact when choices are observed over time to give reciprocal

reinforcement or dilution. Our results contribute to two growing streams of literature: the former

explores how the correlation between different choice situations can influence customers’ choices;

the latter questions the robustness of the pioneer advantage. In particular, our study suggests that

order of entry moderates the compromise effect. As a result, pioneering advantage can be eroded

over time depending on whether the pioneer’s is the dominant or the intermediate brand in the

market. Furthermore, our study shows how different levels of product familiarity can influence the

how robust the pioneering advantage is in face of compromise effect. In particular, we find that low

familiarity, acting on preference uncertainty, serves as driver for the use of the easier and more

explicit cue, which in our case is related to the pioneering status. When familiarity increases, the

more available cue (i.e. order of entry) no longer acts as the principal preference driver, and pioneer

advantage is overcome by the composition of the choice set.

6. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Of course, there are several limitations to our study. First, products were described by only

two attributes, and thus product representation was not complete and the increasing amount of

information that would be available given repeated choices over time was not available.

19

Second, the arrival of followers is usually associated with the introduction of new or enhanced

product attributes, a possibility not considered in our study. Therefore, more effort should be

directed to explore the role of the follower’s product distinctiveness strategy on the strength of

compromise effect, focusing on the balance between extreme and compromise attributes.

Third, the effect of product category familiarity was no manipulated but observed ex-post: this

should be pursued in further study. Finally, the interaction between other context effects (i.e.,

attraction effect) and the pioneering advantage could be further investigated.

20

REFERENCES

Alba, Joseph W., John W. Hutchinson. (1987). “Dimensions of Consumers Expertise”, Journal of

Consumer Research, 13 (March), 411-454

Amir, On and Jonathan Levav. (2006).“Choice Construction versus Preference Construction: The

Instability of Preferences Learned in Context”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol.33, ed.

Gavan Fitzsimons and Vicky Morwitz, Association for Consumer Research.

Bain, Joe S. (1956). Barriers to new competition, Cambridge MA: Harvard Business Press.

Benartzi, Shlomo and Richard R. Thaler. (2002). “How Much Is Investor Autonomy Worth?”,

Journal of Finance, 57 (4), 1593-1616.

Bettman, James R., Eric J. Johnson, and John W. Payne. (1990). “A Componential Analysis of

Cognitive Effort in Choice”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 45,

111-139.

Bond, Ronald S. and David F. Lean. (1977). “Sales, Promotion, and Product Differentiation in Two

Prescription Drug Markets” Economic Report Federal Trade Commission.

Boulding, William and Markus Christen. (2001). “First-Mover disadvantage”, Harvard Business

Review 79 (9).

Carpenter, Gregory S. and Kent Nakamoto. (1988). “Consumer Preferences Formation and

Pioneering Advantage”, Journal of Marketing Research, 26 (August), 285-298.

Chernev, Alexander. (2004). “Extremeness Aversion and Attribute Balance Effects in Choice,”

Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (September), 249-264.

Dhar, Ravi, Stephen M. Nowlis, and Steven J. Sherman. (2000). “Trying Hard or Hardly Trying:

An Analysis of Context Effects in Choice”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9 (4), 189-200.

Dhar, Ravi and Itamar Simonson. (2003). “The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice”, Journal of

Marketing Research, 40 (May), 146–60.

21

Dhar Ravi, Anil Menon, and Bryan Maach. (2004). “Toward Extending the Compromise Effect to

Complex Buying Contexts”, Journal of marketing research, 41 (August), 258-261.

Drolet, Aimee (2002), “Inherent Rule Variability in Consumer Choice: Changing Rules for

Change’s Sake,” Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (December), 293–305.

Huber, Joel, John W. Payne, and Christopher Puto. (1982). “Adding Asymmetrically Dominated

Alternatives: Violations of Regularity and the Similarity Hypothesis”, Journal of consumer

research, 9 (June), 90-99.

Johnson, Eric J. and Edward J. Russo. (1984), “Product Familiarity and Learning New

Information”, Journal of Consumer Research, 11 (1), 542-550.

Kalyanaram, Gurumurthy and Glen L. Urban. (1992). “Dynamic Effects of the Order of Entry on

Market Share, Trial Penetration, and Repeat Purchases for Frequently Purchased Consumer

Goods”, Marketing Science, 11 (3) 235-251.

Kardes, Frank R. and Gurumurthy Kalyanaram. (1992). “Order-of-Entry Effects on Consumer

Memory and Judgment: an Information Integration Perspective”, Journal of Marketing

Research, 29 (August), 343-357.

Kerin, Roger A., Rajan P. Varadarajan and Robert A. Peterson. (1992). “First-Mover Advantage: A

Synthesis, Conceptual Framework and Research Propositions”, Journal of Marketing, 56 (4),

33-53.

Kivetz, Ran, Oded Netzer, and V. “Seenu” Srinivasan. (2004a). “Alternative Models for Capturing

the Compromise Effect”, Journal of marketing research, 41 (August), 237-257.

__________ (2004b). “Extending Compromise Effect Models to Complex Buying Situations and

Other Context Effects”, Journal of marketing research, 41 (August), 262-268.

Moore, Michael J., William Boulding., and Ronald C. Goodstein. (1991). “Pioneering and Market

Share: Is Entry Time Endogenous and Does It Matter?”, Journal of Marketing Research, 28

(1), 97-105.

22

Novemsky, Nathan, Ravi Dhar, Norber Schwartz, and Itamar Simonson. (2004). “The Effect of

Preference Fluency on Consumer Decision Making”, Unpublished Manuscript, Department of

Marketing, Yale University.

Nowlis, Stephen M. and Itamar Simonson. (2000). “Sales Promotions and Choice Context as

Competing Influences on Consumer Decision Making”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9

(1), 1–17.

Robinson, William T. (1988b). “Marketing Mix Reactions to Entry”, Marketing Science, 7 (4), 368386.

Robinson, William. T. and Claes Fornell. (1985). “Sources of Market Pioneer Advantages in

Consumer Goods Industries”, Journal of marketing research, 22 (3), 305-318.

Schmalensee, Richard. (1982). “Product Differentiation Advantages of Pioneering Brands”,

American Economic Review, 72 (June), 349-365.

Shankar, Venkatesh., Gregory S. Carpenter, and Lakshman Krishnamurthi. (1999). “The

Advantages of Entry in the Growth Stage of the Product Life Cycle: An Empirical Analysis”,

Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (2), 269-277.

Sheng, Shibin, Andy M. Parker, and Kent Nakamoto. (2005). “Understanding the Mechanism and

Determinants of Compromise Effects”, Psychology & Marketing, 22 (July).

Simonson, Itamar. (1989). “Choice Based on Reasons: The Case of Attraction and Compromise

Effects”, Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (September), 158-174.

Urban, Glen. L., Theresa Carter, Steven Gaskin, and Zofia Mucha. (1986). “Market Share Rewards

to Pioneering Brands: An Empirical Analysis and Strategic Implications”, Management

Science 32 (6), 645-660.

Zough, Zheng K. and Kent C. Nakamoto. (2007). “The Effect of Enhancing and Distinctive

Features on Product Preferences: the Moderating Role of Product Familiarity”, Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, Forthcoming.

23