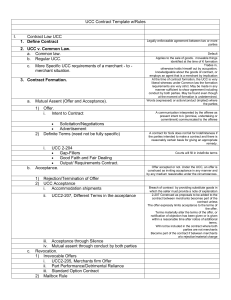

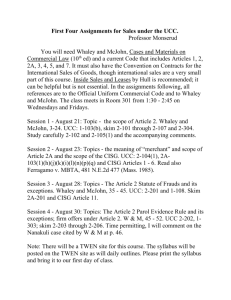

CONTRACTS II – NOTES

advertisement