3. Career Development

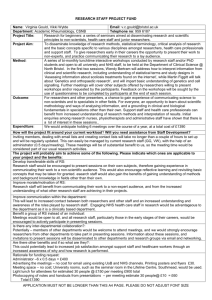

advertisement

Research Staff Conference 27th January 2005 Discussion Paper 1. Background The first Cardiff University Career Development Conference for Research Staff was held on 27th January 2005. The aims of the day were to: provide information on the support available for research staff and the University’s obligations to them; give research staff the opportunity to feed into the post-merger policy review process; provide research staff with the opportunity to meet, and discuss their experiences with, other researchers from across the Institution; raise awareness of the importance of career planning for individual researchers. Delegates were asked to discuss, in groups, the key issues facing research staff at Cardiff, at both School and University levels, and how these impact (positively or negatively) on the career development of researchers. This brief paper summarises the main issues raised by the groups. Each group’s flipchart notes also inform this paper. 2. Benefits Participants identified several benefits of working as a researcher in higher education. The most significant of these is that the work itself is generally both interesting and intellectually stimulating. Many researchers also spoke of enjoying the flexibility and variety afforded by their day-to-day work. Having the opportunity to concentrate purely on research, without having teaching commitments, was also positively regarded. 3. Career Development The main discussion was concerned with research career routes, and how these were identified, sustained and supported. 3.1 Fixed-term contracts Being employed on fixed-term contracts was identified as the most negative aspect of working as a researcher at Cardiff University. The lack of security associated with being on fixed-term contracts can lead to low morale and, in some cases, high levels of stress and even depression. Researchers spoke of the need to constantly scan the horizon for the next post, which, as well as being disruptive and inconvenient in terms of an individual’s personal life, can also have negative effects on individual research projects. 1 It was recognised that, in order to sustain a successful research career in academia, researchers on fixed-term contracts need to concern themselves with three main goals: publishing their work, securing funding for future research, and securing their next contract of employment. Nevertheless, within the tight timescale of an individual research project, time is often not allocated for research staff to engage in these ‘extra-curricular’ activities, nor to participate in training and other career development activities. Additionally, applying for the next research post, or the funding to continue with the present work, is not always recognised as legitimate activity for researchers to engage with during ‘project time’. Researchers spoke of how data is frequently left unanalysed and publications unwritten at the end of research projects. Research staff frequently have to leave projects in order to take up their next position during the crucial data analysis/writing-up phase of the research. This was considered to be an inefficient use of resources. It can also lead to researchers being unable to capitalise on the outcomes of the project. Delegates were keen to see the University tackle redeployment in more imaginative ways: one group, for example, proposed the establishment of a database of researchers, detailing their skills, attributes and research interests, along with details regarding their current contracts. This database would allow collaboration between researchers and potential Principal Investigators elsewhere within the University and could be used to identify job opportunities for researchers. Delegates sought clarity on the University’s future policy with regard to the use of fixed-term contracts for research staff. Although it was recognised that the University’s research income streams are not fixed, researchers at the conference felt that the institution should also shoulder some of the risk associated with this. Delegates recognised that the use of fixed-term contracts differs between disciplines, with a group of researchers in the social sciences pointing out that it was not unusual for researchers in these disciplines to be employed on a series of very short term contracts. The very short-term nature of these contracts served to exacerbate the problems outlined above, which led to a discussion regarding the possibility of imposing a minimum duration onto successive short-term contracts. 3.2 Rewarding selfishness? Many researchers voiced their concern at having to act in what they characterised as a ‘selfish’ way in order to succeed in academia, concentrating on their own priorities and their own careers rather than the priorities of the University, the School or even the research group. There was call for a greater recognition of work which supports research but is not in the form of written publications, such as running labs, training others, and so on. 3.3 Career routes Three main issues were raised with regard to career routes: 2 3.3.1 Traditional routes into academia The first concerned career routes into permanent academic posts. The scarcity of permanent academic posts, particularly in relation to the number of fixed-term researchers, was acknowledged. One group questioned whether there were still clear routes into academia and expressed concern regarding a perceived scarcity of lectureships. 3.3.2 Alternative career routes It was acknowledged that there are alternative career trajectories to the traditional PhD postdoctoral research lectureship route, and that not all researchers wish to pursue an academic career. Many delegates, however, expressed uncertainty regarding the alternative careers that were available for research staff. 3.3.3 Career researchers? Delegates recognised that an individual researcher would generally need to secure a lectureship in order to attain the intellectual freedom to pursue their own research interests. Several groups, however, were keen to stress that many of those engaged in higher education research did not wish to pursue a traditional academic career and wished to note the apparent irony that, in order to sustain a research career, an individual would need to engage more with teaching and less with research. One group asked the panel whether it could be feasible to sustain a purely research-based career. 3.4 Applying for research funding Researchers expressed a lack of certainty as to whether they would be supported by the institution should they wish to apply for their own grants, or indeed, whether research sponsors would consider applications from fixedterm workers. Many researchers were keen to apply for their own funding to combat the lack of intellectual control over the research project which was recognised as a problem in their current roles. 3.5 Reward Concerns were raised regarding the way in which being employed on a series of fixed-term contracts can have negative consequences for an individual’s salary progression. Researchers expressed concerns that as they gained more experience they would become too expensive, and that Principal Investigators would generally prefer to employ less experienced staff as they are cheaper. This leads to more experienced research staff being priced out of the market or forced to take a pay cut to secure their next contract. 4. Wider Structural Issues 4.1 The University and the School A great deal of the discussion concerned researchers not feeling valued by the Institution, and that their contribution towards its successes, particularly in terms of the Research Assessment Exercise, can sometimes go unrecognised. At a more practical level, many researchers at the conference were uncertain as to the position of researchers within the broader University structure: they stated that they had little knowledge of the University, its 3 workings and the relevance of this to researchers, and also of the relationship between the central University and individual Schools. This frequently leads to researchers feeling disconnected from the systems that have been put in place to support them within the University. Some groups expressed frustration at the distance they felt from the decisionmaking processes both within the wider University and within Schools. Communication between decision-makers and researchers was described as haphazard and ad hoc. Some researchers also spoke of feeling isolated within their Schools. Although researchers shared a certain commonality of experience, particularly in relation to being employed on fixed-term contracts, it became apparent from the discussion that there was also huge variety in terms of the lived experience of being a member of research staff at Cardiff. In fact there was even a degree of variability on the fixed-term employment issue with differences across the University in terms of how these were managed by supervisors and even Schools, and even the length of contracts available, as outlined above. A further discrepancy across the University stems from a lack of consistency in nomenclature – with terms such as ‘research associate’, ‘research fellow’, ‘postdoc’, and so on, being used interchangeably. Researchers expressed uncertainty as to the levels of support they were entitled to, not only from Principal Investigators on their individual research projects, but also at School and University levels. It was felt that there were no rules outlining how individual Schools should manage their research staff. Many researchers felt that the University should issue contracts to formalise the opportunities available to researchers to engage in career development activities, including conference attendance, undertaking teaching and taking on supervisory responsibilities. The University should also be more explicit about its expectations of Principal Investigators. 4.2 The Researcher/Principal Investigator Relationship It was acknowledged that the nature of the researcher/principal investigator relationship plays a significant role in determining an individual’s experience of working as a researcher within the University, and that it also has important implications for an individual researcher’s own career development. Several groups pointed to the tension that sometimes arises from the fact that successful academics were not always adept at people management and that it is possible to be in a position with HE where one has line-management responsibility but no management experience or skills. It was felt that Principal Investigators should be given training in the key skills that were required for this role. Delegates recognised that Principal Investigators were generally overworked and subject to high levels of pressure in their own roles. This problem is exacerbated by a lack of incentives for Principal Investigators to become good managers. 4.3 Other Issues 4.3.1 Childcare Provision 4 Childcare presents a particular problem for some, particularly as researchers typically work outside normal office hours whereas crèches do not. 4.3.2 Illness A further concern was raised regarding illness. Although researchers at Cardiff are entitled to sick pay from the beginning of their employment, it is not always possible to extend the research contract. This can lead to work being left incomplete which has important implications for an individual as they try to secure future research contracts. Dr Sara Williams, Training and Development Manager Human Resources April 2005 5