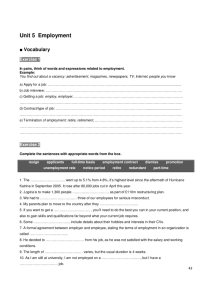

III. Employment Law

advertisement