Stuart Schechter: So many a great computer scientists has stood at

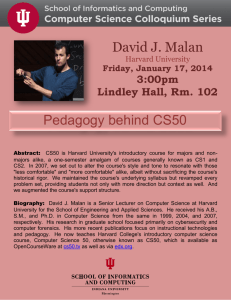

advertisement