Global Staffing & Training: International Operations

advertisement

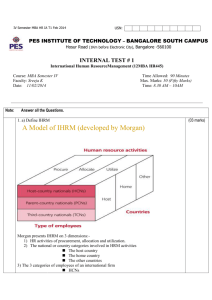

CHAPTER 10 STAFFING AND TRAINING FOR GLOBAL OPERATIONS Opening profile: Oleg and Mark-Equal Work but Unequal Pay The case tracks Oleg and Mark, project managers at the Moscow subsidiary of a multibillion dollar international company. Oleg is a Russian, Mark an American expatriate. While they are the same age and perform similar tasks, Mark’s compensation is considerably higher than that of his domestic peer. Further, Mark has exceptional benefits that Oleg does not enjoy. The two have differing perspectives about the equity of their compensation. I. Staffing Alternatives for International Operations Alternate philosophies of managerial staffing abroad are known as the ethnocentric, polycentric, regiocentric, and global approaches. Firms using the ethnocentric approach fill key managerial positions with persons from headquarters. They use PCNs—parent company nationals. With a polycentric staffing policy, local managers (HCNs - home country nationals) are hired to fill key positions in their own company. One disadvantage of a polycentric policy is the difficulty of coordinating activities and goals between the subsidiary and the parent company, including the potentially conflicting loyalties of the local manager. In the global staffing approach, the best managers are recruited from within or outside of the company, regardless of nationality—a practice used for some time by many European multinationals. Recently, as more major U.S. companies adopt a global strategic approach, they are also considering foreign executives for their top positions. Exhibit 10-1 illustrates a global staffing policy as a means of maintaining globalization momentum. Those firms with a truly global staffing orientation are phasing out the entire ethnocentric concept of a home or host country; and as part of that focus, the term transpatriates is increasingly replacing that of expatriates. In the regiocentric approach to staffing, recruiting is done on a regional basis. II. Global Selection The initial phase of setting up criteria for global selection is to consider which overall staffing approach or approaches would most likely support the company’s strategy. These are typically just starting points using idealized criteria; however; in reality, other factors creep into the process, such as host country regulations, stage of internationalization, and—most often—who is both suitable and available for the position. The selection of personnel for overseas assignments is a complex process. The criteria for selection are based on the same success factors as in the domestic setting, but additional criteria must be considered related to the specific circumstances of each international position. There are five categories of success for expatriate managers: 1) job factors; 2) relational dimensions, such as cultural empathy and flexibility; 3) motivational state; 4) family situation; and 5) language skills. The relative importance of each factor is highly situational and difficult to establish. A more flexible approach to maximizing managerial talent, regardless of the source, would certainly consider more closely whether the position could be suitably filled by a host-country national. This contingency model of selection and training depends on the variables of the particular assignment, such as the length of stay, the similarity with the candidate’s own culture, and the level of interaction with local managers in that job. Most MNCs tend to start out their operations in a particular region by selecting primarily from their own pool of managers. Over time, and with increasing internationalization, they tend to move to a predominantly polycentric or regiocentric policy because of: (1) increasing pressure (explicit or implicit) from local governments to hire locals (or sometimes legal restraints on the use of expatriates); and (2) the greater costs of expatriate staffing, particularly when the company has to pay taxes for the parent-company employee in both countries. In addition, in recent years, MNCs have noted an improvement in the level of managerial and technical competence in many countries, negating the chief reason for using a primarily ethnocentric policy in the past. For MNCs based in Europe and Asia, human resource policies at all levels of the A. Problems with Expatriation When staffing overseas assignments with expatriates, many other reasons, besides poor selection, contribute to expatriate failure among U.S. multinationals. A large percentage of these failures can be attributed to poor preparation and planning for the entry and reentry transitions of the manager and his or her family. One important variable, for example, often given insufficient attention in the selection, preparation, and support phases, is the suitability and adjustment of the spouse. The following is a synthesis of the factors frequently mentioned by researchers and firms as the major causes of expatriate failure: selection based on headquarters criteria rather than assignment needs inadequate preparation training and orientation for the assignment alienation or lack of support from headquarters problems with spouse or children—poor adaptation, family unhappiness insufficient compensation and financial support insufficient compensation poor programs of career support and repatriation III. Training and Development In earlier discussions, the text noted that reports indicate that up to 40 percent of expatriate managers end their foreign assignments early because of poor performance or an inability to adjust to the local environment. About half of the expatriates who do remain function at a low level of effectiveness. The direct cost alone of a failed expatriate assignment is estimated to be from $50,000 to $150,000. The indirect costs may be far greater, depending on the position held by the expatriate. A. Cross cultural training Even though cross-cultural training has prove to be effective, less than a third of expatriates are given such training. In a 1997 study by Harvey of 332 U.S. expatriates (dual-career couples) the respondents stated that their MNCs had not provided them with sufficient training or social support during the international assignment. Much of the rationale for this lack of training is an assumption that managerial skills and processes are universal. The demands on expatriate managers have always been as much a result of the multiple relationships that they have to maintain as they are of the differences in the host-country environment. Those relations include family relations, internal relations with people in the corporation, both locally and globally, especially with headquarters, external relations (suppliers, distributors, allies, customers, local community, etc.), and relations with the host government. It is important to pinpoint any potential problems that an expatriate may experience with those relationships so that these problems may be addressed during pre-departure training. The model shown in Exhibit 10-4 presents various development methods to address these areas during pre-departure training, post-arrival training, and reentry training. B. Training Techniques Many training techniques are available to assist overseas assignees in the adjustment process. These techniques are classified by Tung as: (1) area studies; that is, documentary programs about the country’s geography, economics, socio-political history, and so forth; (2) culture assimilators, which expose trainees to the kinds of situations they are likely to encounter that are critical to successful interactions; (3) language training; (4) sensitivity training; and (5) field experiences—exposure to people from other cultures within the trainee’s own country. Similarly categorizing training methods, Ronen suggests specific techniques, including a field experience called the host-family surrogate, where the MNC pays for and places an expatriate family with a host family as part of an immersion and familiarization program. Exhibit 10-5 shows this and other training methods, some examples of the techniques used for each method, and the purpose of each. Most training programs take place in the expatriate’s own country prior to leaving. While this is certainly a convenience, the impact of host-country (or in-country) programs can be far greater than those conducted at home because crucial skills, such as overcoming cultural differences in intercultural relationships, can actually be experienced during in-country training rather than simply discussed. Exhibit 10-6 shows some global management development programs for junior employees. C. Integrating Training with Global Orientation It is important to remember that training programs, like staffing approaches, be designed with the company’s strategy in mind. Exhibit 10-7 suggests levels of rigor and types of training content appropriate for the firm’s managers, as well as those for host country nationals, for four globalization stages. D. Training Host-Country Nationals IV. The continuous training and development of HCNs and TCNs for management positions is also important to the long-term success of multinational corporations. As part of a long-term staffing policy for a subsidiary, the ongoing development of HCNs will facilitate the transition to an indigenization policy. Expatriate Compensation The significance of an appropriate compensation and benefit package to attract, retain, and motivate international employees cannot be overemphasized. There must be a "fit" between compensation and the goals for which the firm wants managers to aim. The premature return of expatriates or the unwillingness of managers to take overseas assignments can often be traced to their knowledge that the assignment is detrimental to them financially, and usually to their career progression. The high cost of maintaining the expenses and appropriate compensation packages for expatriates has led many companies to cut back on overseas assignments as much as possible. The ability to design and maintain an appropriate package is more complex than it would seem because of the need to consider and reconcile parent and host country financial, legal, and customary practices. Exhibit 10-8 provides an example of a compensation score card for expatriate managers. To assure that expatriates do not lose out through their overseas assignment, the balance sheet approach is often used to equalize the standard of living between the host country and the home country and to add some compensation for the inconvenience or qualitative loss. (See Exhibit 10-9). In fairness, the MNC is obliged to make up additional costs the expatriate would incur for taxes, housing, and goods and services. The tax differential is complex and expensive for the company, and generally MNCs use a policy of tax equalization: the company pays any taxes due on any type of additional compensation that the expatriate receives for the assignment; the expatriate pays in taxes only what she or he would be paying at home.