David R. Cleveland - Nonpublication.com

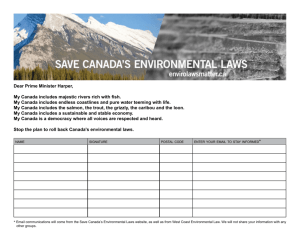

advertisement