The Feed-in Tariff Controversy - Society of International Economic Law

advertisement

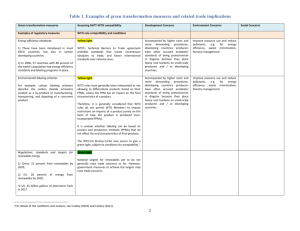

THE FEED-IN TARIFF CONTROVERSY: RENEWABLE ENERGY CHALLENGES IN WTO LAW ANDREW JERJIAN I. INTRODUCTION The future policy landscape for the promotion of renewable energy (RE) has the potential to be shaped by the legal treatment of feed-in tariff (FIT) programmes under the international trading system. A FIT is an instrument for promoting investment in RE and typically sets a fixed price for purchases of RE power, providing electricity producers with a premium above the market price for electricity—per kilowatt-hour (kWh)—fed into the grid. 1 FIT programmes have been implemented in about fifty jurisdictions worldwide, at either a national or sub-national level.2 The catalyst for the international proliferation of the FIT model is, in part, the desire to emulate the success of other jurisdictions—especially Germany—in achieving more decentralized, carbon-neutral domestic energy production.3 Despite the growing prevalence of FIT programmes, the global RE landscape has more recently been called into question. This issue emanates from WTO actions launched by Japan and the EU against Canada in relation to Ontario’s FIT programme. While the case specifically concerns the legitimacy of domestic content requirements for eligibility in Ontario’s FIT programme, the proceedings also pose more systemic concerns with respect to FITs—as a “subsidy” at risk of being challenged and lacking clear status as a matter of WTO law. The recent WTO disputes concerning Ontario’s FIT programme will have a detrimental impact on the RE sector, possibly spurring fragmentation of RE policy in the coming years. Not only are the potential ramifications of the panel decisions inimical to the future cohesion of the global RE sector, but they will also serve as a litmus test for the WTO regime’s sustainable development credentials. With systemic issues at stake, the WTO can help Canada and others by providing more transparent and progressive rules on subsidies, while remaining vigilant and alert to the danger of protectionism under the guise of such subsidies. This paper will first explore the origins and operation of the FIT instrument in Germany and Ontario. In doing so, the stage will be set for the examination of the WTO definition of subsidy and requirements for liability—focusing initially on “actionable” subsidies in the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM). Furthermore, the FIT programmes of Ontario and Germany will be analysed under the ASCM. This will then be complemented by an examination of “prohibited” subsidies under WTO law and the current controversy on domestic content requirements. Ultimately, the WTO must be more accepting of RE public support mechanisms and should provide greater flexibility to the extent required by the needs of nations in pursuit of sustainable development objectives. 1 Mendonça et al, Powering the Green Economy: The Feed-in Tariff Handbook (Earthscan 2010) xxi. 2 Renewable Energy Policy Network <http://www.ren21.net/RenewablesPolicy/OverviewonPolicyInstruments/RegulatoryPolicies/Fee dinTariff/tabid/5628/Default.aspx> accessed 8 September 2012. 3 Grinlinton and Paddock, ‘The Role of Feed-in Tariffs in Supporting the Expansion of Solar Energy Production’ (2009) 41 U Toledo LRev 942, 945. 2 II. BACKGROUND TO FEED-IN TARIFFS This Chapter will examine the origins of FIT programmes and their development within Germany and Ontario. AN OVERVIEW: HISTORY & ORIGINS Germany was the first European nation to pioneer a feed-in law incentive scheme for the development of RE production.4 Although the energy industry was hostile to the notion of new decentralized competition, political support led to the introduction of the Electricity Feed-in Law 1990 (Stromeinspeisungsgesetz, StrEG). The StrEG required utilities to provide renewable energy generators grid access and purchase the energy produced. Remuneration for the energy was correlated to average price of electricity per kWh sold to final consumers; for wind and solar power, the rate was fixed to 90% of this end-user price.5 One of the declared purposes of the law was to “level the playing field” for renewable energy.6 Germany’s Renewable Energy Sources Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz, EEG) was adopted to improve upon the former StrEG and foster greater expansion of RE production within Germany’s energy portfolio. Some of the more crucial elements of the EEG include the decoupling of rates from electricity prices, fixed rate guarantees for twenty-year terms, and the establishment of tariff differentiation according to the source, size and location of renewable energy plants.7 More recently, the Act’s innovations were taken further under a 2012 amendment. Among other developments, the revised legislation refined the purpose of the EEG by enumerating previously enshrined objectives in more exacting terms. The Act’s purpose expressly incorporates goals such as the development of new RE technologies and reduction of energy costs, as well as a 35% renewables target for the domestic energy supply—to be achieved by 2020. 8 Germany’s FIT programme does not rely upon a State actor for the provision and management of FIT payments. It imposes a purchase obligation on private distribution and transmission system operators—collectively involved in the transmission of electric power from the point of generation to consumption—to purchase and share the costs of paying the EEG-imposed tariff to RE producers. Inspired by Germany’s successful promotion of RE using the FIT model,9 Ontario sought to adopt its own “European-style” FIT instrument.10 This was achieved through 4 Mendonça, Feed-In Tariffs: Accelerating the Deployment of Renewable Energy (World Future Council 2007) 27. 5 Jacobbson and Lauber, ‘Germany: From a Modest Feed-in Law to a Framework for Transition’ in Lauber (ed), Switching to Renewable Power: A Framework for the 21st Century (Earthscan 2005) 122, 134. 6 ibid. 7 Laird and Stefes, ‘The Diverging Paths of German and United States Policies for Renewable Energy: Sources of Difference’ (2009) 37 Energy Policy 2619, 2624. 8 EEG 2012, §1. 9 Ontario Legislative Assembly Debates (Hansard), 39th Parl, 1st Sess, 23 February 2009, 4937, 4952. 10 Rothman and Dalton, ‘Ontario’s Feed-in Tariff: Can a European-style renewable model work in the Americas?’ (October 2009) Public Utilities Fortnightly 22, 22; Interview with George Smitherman, former Duty Premier and Minister of Energy of Ontario (Toronto, 2 January 2012). 3 the Green Energy and Green Economy Act 2009 (GEGEA), which enacted the Green Energy Act. Ontario’s FIT programme is divided into two streams: the FIT and the microFIT.11 The FIT is applicable to projects generating more than 10 kW, while the microFIT targets individuals interested in more small-scale projects not exceeding the aforesaid threshold. The Preamble of the Green Energy Act enunciates that the legislation strives to secure “cleaner sources of energy” as well as the promotion of both RE projects and a “green economy”. According to the Minister of Energy at the time of the proposed legislation, the policies embedded within the legislation are intended to make Ontario one of the “greenest energy supply mixes in the world.”12 The FIT programme also aims to create a new “green industry” by requiring solar and wind facilities to meet domestic content requirements—currently, 60% and 50% for solar and wind respectively.13 These objectives illustrate the dual environmental and economic policy impetus underlying Ontario’s FIT programme. Ontario’s FIT programme is managed and implemented by the Ontario Power Authority (OPA).14 Under GEGEA, the OPA is required to comply with the Minister of Energy’s directions in relation to activities such as the procurement of electricity supply and development of a FIT programme. Although the Electricity Act 1998 describes the OPA as not being a Crown Corporation, the Ministry of Energy has delegated to the OPA the responsibility for setting the FIT and administering FIT contracts.15 With respect to financing, FITs are partially funded by the Global Adjustment Mechanism (GAM). GAM appears as a charge on consumer bills and funds the shortfall between the market price and the guaranteed FIT—which, like in Germany, is provided for a twenty-year period.16 Yatchew and Bazilauskas, ‘Ontario Feed-in-Tariff Programs’ (2011) 39 Energy Policy 3885, 3888. 12 George Smitherman, Ontario Legislative Assembly Debates (Hansard), 39th Parl, 1st Sess, 23 February 2009, 4937, 4952. 13 FIT Rules, s 6.4(a) <http://fit.powerauthority.on.ca/sites/default/files/FIT%20Rules%20Version%201%205%201_Pr ogram%20Review_0.pdf> accessed 15 September 2012. 14 OPA, ‘FIT Program Overview’ (2010) 2. 15 EA 1998, s 25.1-25.3. 16 AG, ‘Annual Report of the Auditor General of Ontario’ (2011) 93; OPA, ‘FIT Program Overview’ (2010) 30. 11 4 III. SUBSIDIES: WTO LAW FRAMEWORK The development of FIT programmes worldwide has introduced new challenges for the existing framework established by the WTO’s law of subsidies. In this Chapter, the WTO’s perspective on the matter of subsidies will be examined. An overview will be provided in Chapter IV of the case against Canada (concerning the Ontario scheme), and reforms which the WTO may adopt—clarifying the matter of subsidies in the RE sector for the future. A. THE WTO’S APPROACH TO SUBSIDIES (1) DEFINING SUBSIDIES UNDER THE ASCM After failing to resolve the dispute with Canada during consultations, Japan and the EU (the “Members”) each sought to establish a panel pursuant to Article 6.1 of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Understanding.17 The Members specifically argue that Ontario’s FIT is a “prohibited” subsidy under the ASCM (WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures) because it is contingent on the use of domestic content. More specifically, Ontario’s FIT Rules and FIT Contract both establish that all solar and wind project capacities over 10kW must meet a minimum required domestic content level. Prior to determining whether Ontario’s FIT violates the WTO law of subsidies, it is vital to underscore a distinction that is drawn between “prohibited” and “actionable” subsidies under the ASCM. Article 3 ASCM makes clear that subsidies linked to export performance or the use of local content are categorically prohibited. By contrast, nonprohibited subsidies require proof of adverse effects (Article 5) and specificity (Article 2), thereby being only potentially “actionable”. With respect to prohibited subsidies, Article 3.1(b) prohibits “subsidies contingent, whether solely or as one of several other conditions, upon the use of domestic over imported goods.” In order to conclude that a measure is “actionable” or “prohibited”, one must analyse whether Ontario’s FIT can be classified as a subsidy under the ASCM. (a) The First Prong: Financial Contribution or “Price Support” Under Article 1 ASCM, the definition of a subsidy effectively rests on two prongs: (1) the existence of a “financial contribution” or income or price support; and (2) conferral of a benefit upon the recipient. The concept of financial contribution—albeit acting as an initial control-valve to ASCM disciplines—has been interpreted quite flexibly. In Canada–Measures Affecting the Export of Civilian Aircraft (Canada–Aircraft), the Appellate Body held that the question of whether Article 1 requires a “cost to government” is relevant to the interpretation of “financial contribution”, not as to whether a benefit has been conferred—as suggested by Canada. In concluding that a financial burden for the State is unnecessary, it noted that: Canada’s interpretation of ‘benefit’ would exclude from the scope of that term those situations where a ‘benefit’ is conferred by a private body under the direction of government. These situations cannot be excluded from the definition of ‘benefit’ Japan: Canada–Certain Measures Affecting the Renewable Energy Generation Sector, WT/DS412/5 (7 June 2011); EU: Canada–Measures Relating to the Feed-in Tariff Program, WT/DS426/5 (10 January 2012). 17 5 in Article 1.1(b), given that they are specifically included in the definition of ‘financial contribution’ in Article 1.1(a)(iv).18 The relevance of this decision vis-à-vis government expenditure is therefore linked to an important distinction under Article 1.1—namely, that financial contributions may be either direct or indirect.19 (i) Direct Financial Contribution Direct financial contributions are those that are provided by the government or a public body. Article 1.1(a)(1) exhaustively enumerates four forms of financial contribution, with paragraphs (i)-(iii) being direct in nature. In the context of FIT programmes, paragraph (iii) is especially relevant, as it concerns the “purchase of goods” by a government or public body. Given that electrical energy may be defined as a good under WTO law,20 the more critical question centres on the interpretation of “public body”. Until recently, Korea–Measures Affecting Trade in Commercial Vessels (Korea–Commercial Vessels)21 was authority for the view that an entity is a public body where it is controlled by the government. In this matter, the panel’s affirmative finding of a public body was supported “primarily” on the basis that the entity was 100% owned by the Korean government (or other public bodies).22 This conception of a public body as hinging on the concept of control was hewn in the recent case of United States–Definitive Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties on Certain Products from China (US–AD/CVD),23 where the Appellate Body decided that evidence of a “controlling interest”24 is itself not sufficient to establish that an entity is a public body. It elaborated that the ability to perform the functions of entrusting or directing private bodies are “core commonalities” between government and public body. In this respect, while any single characteristic—like a controlling financial stake—is not decisive, “meaningful [government] control over an entity and its conduct may serve … as evidence that the relevant entity possesses governmental authority and exercises such authority in the performance of governmental functions”25 [emphasis added]. The Appellate Body also asserted that the classification of an entity’s functions as governmental under the “legal order” of the relevant Member may be a “relevant”—yet not a definitive—consideration in the determination of public body. (ii) Indirect Financial Contribution By contrast, indirect financial contributions are those that originate from or are channelled through private bodies to a beneficiary. Such forms of contribution are addressed specifically under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iv) and entail different imputability criteria 18 Canada-Aircraft, WT/DS70/AB/R (1990), para 160. Matsushita et al, The World Trade Organization: Law, Practice, and Policy (OUP 2006) 343. 20 Cottier et al, ‘Energy in WTO Law and Policy’ in Cottier and Delimatsis (eds), The Prospects of International Trade Regulation (CUP 2011) 215. 21 Korea–Commercial Vessels, WT/DS273/R (2005). 22 ibid, para 7.50. 23 US–AD/CVD, WT/DS379/AB/R (2011); Wilke, ‘Feed-in Tariffs for Renewable Energy and WTO Subsidy Rules: An Initial Legal Review’ ICTSD (2011) 21. 24 US-AD/CVD, para 320. 25 ibid, paras 318-9. 19 6 compared to direct financial contributions. 26 Paragraph (iv) provides that government payments to a “funding mechanism” are defined as financial contributions. Alternatively, indirect financial contributions also exist where: (1) the government or public body “entrusts or directs” a private body; (2) to carry out a “function(s) illustrated in (i)-(iii)”; (3) which would “normally be vested in the government”; and (4) the “practice, in no real sense, differs from “practices normally followed by governments”. Where a private body is used as a “proxy”27 by the “government” to carry out the functions listed in paragraphs (i)-(iii), paragraph (iv) is applicable even absent any cost to government. The “real gateway”28 to regulation under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iv) is that the type of function undertaken by the private entity must represent a “function” or “practice” normally vested in government—with respect to both the relevant WTO Member and as a normative matter. These provisos impose a heightened evidential and analytical burden, and are “one of the most controversial aspects of WTO subsidy law.” 29 As a starting point, consideration must be given to the legal order of the specific Member in order to determine whether the relevant function “would ordinarily be considered part of [its] governmental practice”. 30 However, in United States–Measures Treating Export Restraints as Subsidies (US–Export Restraints), the panel held that the ‘normal practice by governments’ criterion is a reference to the delegation to private bodies of the functions of taxation and expenditure “and not a reference to government market interventions in the general sense, or the effects thereof.” 31 The panel in Korea– Commercial Vessels more recently reaffirmed this position.32 Nevertheless, the unduly narrow conclusions of these panels are antithetical to the Appellate Body’s interpretation of paragraph (iv) in Canada–Aircraft. Rubini has correctly argued that where “normal government practice” is equated to the power of taxation and expenditure, it would “by necessity imply that financial contribution always requires a cost to government which was rejected by the Appellate Body itself.”33 (iii) “Price Support” At this juncture, it is appropriate to mention the alternative to financial contribution that is expressed in Article 1.1(a)(2), which permits a subsidy to be found where there is income or price support “in the sense of Article XVI of GATT”. The reference to Article XVI means that the measure must operate to increase exports or decrease imports of the relevant (or competing) product. Although this provision has not yet been extensively addressed, the Appellate Body in United States–Final Countervailing Duty Determination with respect to Softwood Lumber from Canada (US–Softwood Lumber) 26 Matsushita et al (n 19) 343. US-DRAMS, WT/DS296/AB/R (2005), para 108. 28 Rubini, ‘The Subsidization of Renewable Energy in the WTO: Issues and Perspectives’ (2011) NCCR Trade Working Paper, 21 <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1904267> accessed 1 October 2011. 29 Wilke (n 23) 15. 30 US-AD/CVD, para. 297. 31 US-Export Restraints, WT/DS194/R (2001), para 8.72; Wilke (n 23) 16. 32 Korea-Commercial Vessels, para 7.30. 33 Rubini (n 28) 22. 27 7 affirmed that government subsidisation measures are “broadened still further” 34 by the concept of income or price support. Furthermore, although a 1960 GATT Panel35 held— in relation to price support schemes—that Article XVI requires a “loss to government”, this interpretation appears “outdated”36 in light of the conclusion in Canada–Aircraft that a cost to government is not implicit in the general concept of a subsidy. (b) The Second Prong: “Benefit” The second element necessary to the determination of a subsidy is the conferral of “benefit”. This criterion focuses exclusively on the advantage to the recipient and is legally distinct from the question of financial contribution (or income or price support).37 In conducting the benefit analysis, the panel in European Communities–Countervailing Measures on Dynamic Random Access Memory Chips from Korea (EC–DRAMS) agreed with the Appellate Body in Canada–Aircraft, which stated that the finding of a “benefit” implies that the recipient is “better off” than it would have been absent the contribution.38 As a corollary, it found that the “appropriate basis” for determining the existence of a benefit is the marketplace. 39 This so-called “private investor-test” 40 shares symmetry with—and is indeed inspired by—Article 14 ASCM. With respect to financial contributions under Article 1.1(a)(iii), Article 14(d) establishes that the benchmark in determining the calculation of the benefit is the “adequacy of the remuneration … in relation to prevailing market conditions”. This benchmark has been held by the Appellate Body to be the “relevant context for the interpretation of ‘benefit’ in Article 1.1(b)”.41 However, in the context of energy, Howse has argued that a “meaningful” market benchmark remains elusive given that it has been historically distorted by government intervention in favour of fossil fuels.42 This complements Sykes’s argument that subsidies may actually offset the effects of government intervention by serving as a “corrective” measure.43 This is a question for reform, as the market price is the relevant benchmark due to the fact that Article 14(d) refers expressly to “prevailing” rather than free market conditions. 34 US-Softwood Lumber, WT/DS257/AB/R (2004), para 52. Review pursuant to Article XVI:5, L/1160 (1960), para 11; Rubini, ‘The Definition of Subsidy and State Aid: WTO and EC Law in Comparative Perspective’ (OUP 2009) 123. 36 Bigdeli, ‘Incentive Schemes to Promote Renewables and the WTO Law of Subsidies’ in Cottier et al (eds), International Trade Regulation and the Mitigation of Climate Change (CUP 2009) 171. 37 Canada-Aircraft, para 157. 38 EC-DRAMS, WT/DS299/R (2005), para 7.176. 39 ibid. 40 Matsushita et al (n 19) 347. 41 Canada-Aircraft, para 155. 42 Howse, ‘Post-Hearing Submission to the International Trade Commission: World Trade Law and Renewable Energy: The Case of Non-Tariff Measures’ REIL (2005) 20. 43 Howse, ‘Climate Mitigation Subsidies and the WTO Legal Framework: A Policy Analysis’ IISD (2010) 6. 35 8 (2) ANALYSING FIT PROGRAMMES UNDER THE WTO SUBSIDIES REGIME (a) An Assessment under the ASCM FIT programmes may constitute a financial contribution where they involve the purchase of goods (i.e. electricity) by a government (or public body) under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iii), or by private body under paragraph (iv). For Ontario, the OPA is a State enterprise accountable to the provincial government and responsible for the FIT programme’s implementation, with the authority to enter into FIT contracts with private parties. In light of the Appellate Body decision in US–AD/CVD, the OPA may be deemed to possess “governmental authority”; this is because of its authority to administer the FIT programme and to impose charges on consumers in order to fund its operation. The OPA is also subject to “meaningful” governmental control, as it receives ministerial instruction vesting it with the authority to perform its functions. Although Canada will attempt to assert that the OPA is not a public body, the ruling in US–AD/CVD provides much scope for the conclusion that the entities concerned are exercising governmental authority. 44 Even if the OPA were defined as a private body, it is arguable that the OPA’s GAM may qualify as an indirect “funding mechanism” under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iv), thereby establishing a subsidy through their implication in the administration of public funds.45 In Germany, there is no State enterprise analogous to that of the OPA. The obligation to operate the FIT programme is imposed directly upon the distribution and transmission system operators—which are private bodies. The EEG statutorily “directs” such private parties to purchase electricity sourced by RE technologies. This delegation or instruction to purchase goods—as expressed in Article 1.1(a)(1)(iii)—would satisfy the imputability standards within paragraph Article 1.1 (a)(1)(iv). As supported by the Appellate Body decision in US–Softwood Lumber, the absence of a cost to the German government does not affect the existence of a financial contribution. Furthermore, it may found that purchasing goods is a function that is normally vested in the German government and is a practice generally “followed by governments”. What is “normal” is an empirical question. However, the concept is sufficiently flexible to give “precedence to decisions informed by broader policy—we could say teleological—considerations.”46 The ‘normal function or practice’ provisos within Article 1.1(a)(iv) would likely receive a wide interpretation in order to guard against the calculated circumventions of the financial contribution criterion. By way of example, the international prevalence of FIT programmes and the practice of State procurement of electricity may permit one to infer that the purchase of goods may be one of the “functions of [governmental] entities within WTO Members generally”. 47 This functional approach to interpretation (and deduction) vis-à-vis determining practices “normally followed by governments” would allow a decision on this question to be more accessible, while nevertheless anchoring inferences in empirical observations. It would also permit a compromise to be achieved between paragraph (iv)’s two principal functions—namely, limiting forms of government action regulated by the ASCM and acting as an “anticircumvention”48 mechanism. 44 US-AD/CVD, para 318. Wilke (n 23) 14. 46 Rubini (n 28) 21. 47 US-AD/CVD, para 297; Rubini, ‘The Subsidization of Renewable Energy’ (n 28) 23. 48 Rubini, The Definition of Subsidy and State Aid (n 35) 114. 45 9 Alternatively, FITs may constitute a form of “price support” under Article 1.1(a)(2). 49 This is premised on the fact that FIT programmes maintain the price of electricity generated by RE producers at a desired level in order to offset the high cost of RE technologies and to incentivise production. Howse has argued that FITs “ought not to be considered price support”, as it would be intrusive to the regulatory State to interfere with price regulation, which may serve public policy goals. Howse’s view seems incongruous with the “broad and unqualified” 50 nature of the provision—referring to “any form” of price support—and the fact that this would also provide too easy and broad a method of circumventing its rules. Furthermore, because FIT programmes reduce the need for energy imports and render higher export levels possible, 51 Article XVI GATT is also satisfied insofar as it must be read cumulatively with Article 1.1(a)(2). There is a strong case that FIT programmes constitute a financial contribution and/or price support. Ontario’s FIT programme involves a contractual purchase and therefore a direct financial contribution under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iii), whereas Germany’s be could be analysed as an indirect financial contribution under paragraph (iv). By contrast, Germany longstanding FIT programme would constitute a financial contribution under Article 1.1(a)(1)(iv). Nevertheless, even absent a “financial contribution”, Article 1.1(a)(2) reference to “price support” provides an alternative route to defining FITs as subsidies. Furthermore, FIT programmes by definition confer a benefit on the recipient. This is because FITs are designed to provide RE producers with above-the-market-price remuneration. As per EC–DRAMS, a differential between the payment and market price is direct evidence that a benefit has been conferred. This conclusion is further buttressed by Article 14(d)’s reference to “prevailing market conditions” in determining the existence of a benefit. With the above considerations in mind, it is “reasonable to conclude that feed-in tariffs … should, and could, amount to subsidies under WTO law.” 52 This is more broadly supported by Cottier et al.—Cottier himself being the Chairman of the WTO panel in the pending cases against Canada—who state that “much of the support provided to the RE sector takes the forms which fit the definition of a subsidy according to Article 1 of the ASCM.”53 (b) (In)applicability of GATT Article XX It is pertinent briefly to highlight the unresolved debate on the applicability of Article XX GATT to other WTO Agreements. In relation to the ASCM, this question is important because it concerns the extent to which RE subsidies otherwise in violation of the ASCM could be held WTO-compatible. The exceptions within Article XX(b) and (g) have been held to encompass measures aimed at protecting the environment.54 The former applies to 49 Bigdeli (n 36) 171-2. Rubini, The Subsidization of Renewable Energy’ (n 28) 23. 51 Case C-279/98 PreussenElektra [2001] ECR I-2099, para 70. 52 Rubini, ‘The Subsidization of Renewable Energy’ (n 28) 23. 53 Cottier et al (n 20) 226. 54 US-Gasoline, WT/DS2/AB/R (1996) and Brazil-Tyres, WT/DS332/AB/R (2007); Condon, ‘Climate Change and Unresolved Issues in WTO Law’ (2009) 12 JIEL 895, 911-3. 50 10 measures “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health”, whereas the latter concerns those “relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources”. The availability of Article XX GATT as a defence to ASCM violations remains an open question, as WTO dispute settlement has not directly addressed the issue. In this respect, Howse follows the view that the “lack of textual support … makes it unlikely that the Appellate Body would accept an Article XX defence to a claim” under the ASCM.55 Notwithstanding the above debate, as the issue of environmental subsidies is being addressed in the Doha Round, the Appellate Body is likely to be reluctant to compromise negotiations through a “heroic approach to interpretation”56 to fill the textual void in the ASCM. (3) REQUIREMENTS FOR “ACTIONABLE” SUBSIDIES By virtue of the prevalence of FIT programmes as a RE policy mechanism, it is instrumental to examine whether FITs—as separate from domestic content requirements—might be “actionable” under subsidy disciplines. Once a subsidy is found to exist, actionability rests on proof of specificity (Article 2) and adverse effects (Article 5). Evidence of specificity requires that the subsidy be specific to certain enterprises or industries. Such evidence need not be adduced in relation to “prohibited” subsidies because such subsidies are deemed to be specific under Article 2.3 ASCM. Article 2.1 ASCM covers both de jure and de facto specificity, and stipulates that specificity is absent where subsidies are generally available on the basis of neutral, objective criteria. In this respect, FITs are not “sufficiently broadly available throughout an economy as not to benefit a particular limited group of producers of certain products”.57 The second element hinges on the presence of “adverse effects”. This reflects the principle that only subsidies causing actual trade effects should be subject to the WTO’s multilateral disciplines. Under Article 5 ASCM, causation must be established between the subsidy and one of three possible “adverse effects”: (a) injury to domestic industry; (b) nullification and impairment of benefits accruing under the WTO Agreements; and (c) serious prejudice to a Member’s interests. Serious prejudice is arguably “somewhat easier to prove”58 than Article 5(a) and (b) ASCM. Article 6 ASCM permits this finding on the basis that the effect of the subsidy is to displace or impede the imports of a “like product” into the subsidizing State. For the purposes of the ASCM, the panel in Indonesia– Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry (Indonesia–Autos) addressed the concept of “like products” by stating that physical characteristics are important in assessing which products closely resemble the product under consideration—while also noting the relevance of non-physical characteristics such as “consumer perception”.59 If all energy or even a “class” thereof—such as RE—is treated as a “like product”, it may indeed be claimed that FITs produce adverse effects. One possible future claim may be that foreign-produced non-renewable energy or inputs have been Howse, ‘Climate Mitigation Subsidies’ (n 43), 17. Condon (n 54) 903. 57 US-Cotton WT/DS267/R (2004), para 7.1142; Rubini, ‘The Subsidization of Renewable Energy’ (n 28) 27. 58 Green, ‘Trade Rules and Climate Change Subsidies’ (2006) 5 World Trade Review 377, 402. 59 Howse, ‘Climate Mitigation Subsidies’ (n 43) 14; Indonesia-Autos WT/DS54/R (1998), paras 14.173-6. 55 56 11 prejudiced by a heightened demand for RE.60 Alternatively, within the global RE sector, an adverse effect may arise where a FIT programme incorporates a purchase obligation favouring domestic RE production at the expense of imports, or because tariff differentiation renders particular RE sources and technologies more financially attractive than others.61 Furthermore, although proving causation in the context of a highly distorted global energy market would be difficult, decisions “tend to actually focus on correlation more than causation”—thereby lowering the evidential standards for actionability. 62 Causation may nonetheless be more easily established within regional energy markets— like North America, where the market is “close to non-distorted”.63 Howse, ‘Post-Hearing Submission’ (n 42) 23. Bigdeli (n 36) 183-5; Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead? The Expired Non-Actionable Subsidies and the Lingering Question of “Green Space”’ (2012) 8 MILJ 2, 29. 62 Green (n 58) 402. 63 Wilke (n 23) 18. 60 61 12 IV. FIT PROGRAMMES: CURRENT CONTROVERSY & FUTURE SUBSIDIES REFORM This Chapter will analyse the legitimacy of FIT programmes with respect to domestic content requirements—being a form of “subsidy” in themselves—from a WTO perspective. A. ANALYSING DOMESTIC CONTENT ISSUE: WTO REQUIREMENTS FOR “PROHIBITED” SUBSIDIES In order to be classified as a “prohibited” subsidy, Article 3 ASCM requires—rather succinctly—that the subsidy be contingent on export performance or the use of domestic over imported goods. Where access to a subsidy is conditioned upon achieving a certain level of exports or the obligation to provide location-specific economic support, such subsidies are presumed to be inherently trade-distortive and therefore harmful to the international trading system. With respect to whether Ontario’s FIT programme constitutes a “prohibited” subsidy, eligibility for the programme incorporates domestic content requirements. As per the original direction by George Smitherman—as Minister of Energy—to the OPA, the domestic content requirements were set exclusively for wind and solar facilities.64 This was 25% for wind projects with a milestone date of commercial operation prior to 1 January 2012, thereafter increasing to 50%. In relation to solar projects, content levels were initially set at 40% and 50% for those under the microFIT and FIT programmes, respectively, but have been set uniformly at 60% since 1 January 2011. 65 Therefore, to the extent required by the relevant threshold, a minimum level of inputs—goods and services—for constructing RE generation facilities must be manufactured or provided in Ontario. 66 The OPA has facilitated this compliance calculation by producing various tables—specific to project capacity and the technology deployed—listing designated activities with corresponding qualifying percentages. On this basis, Ontario’s FIT is a prohibited subsidy under Article 3 of the ACSM because access to the FIT is expressly contingent on the use of a certain level of inputs sourced within Ontario. From an institutional perspective, the WTO would consider domestic content requirements as being detrimental to international and domestic trade flows. This is rooted in the fact that the designated activity percentages set by the OPA in 2009 are not subject to periodic review. Such percentages were set in a manner that reflected—at the time—the average total cost of the particular products or services in relation to the overall project.67 Where discrepancies exist between the set percentage and the current real costs, this would cause those constructing RE facilities to purchase within Ontario those products reflecting the lowest possible cost and providing the highest optimal percentage toward the domestic content threshold. This prejudices certain types of Ontario manufacturers because circumstances dictate that RE producers purchase such products in-province. Similarly, this impairment of economic freedom operates to the detriment of foreign manufacturers, as those products purchased within Ontario will not be purchased 64 Direction from George Smitherman to Colin Anderson (24 September 2009) 2-3. FIT Rules, s 6.4(a). 66 FIT Rules, Exhibit D—Domestic Content. 67 Interview with Amir Shalaby, Vice President of Power System Planning at OPA (Toronto, 11 January 2012). 65 13 abroad. Although Germany’s system has no such feature, FIT programmes in countries such as Italy and India have domestic content provisions which also engender concerns.68 B. REFORMING WTO LAW ON SUBSIDIES The creation of a more receptive WTO framework for RE subsidies can be viewed in the context of four possible strategies for moving forward. These encompass either utilising or expanding existing Agreements, or the creation of new substantive and procedural frameworks. (1) UTILISING OR MODIFYING EXISTING AGREEMENTS (a) An Interpretive Approach to Increasing RE Policy Scope One method of expanding RE policy space within the WTO subsidies disciplines is to limit the scope of its application.69 In the EU’s landmark PreussenElektra case70—which analysed whether Germany’s FIT programme under the StrEG constituted State aid—the European Court of Justice [now the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)] endorsed AG Jacobs’s view that it is “preferable that legislation regulating the relationship between private actors is as a matter of principle excluded from the scope of State aid rules.”71 As a means of accommodating RE policy measures, the WTO panels and the Appellate Body could exclude “regulatory measures” from the ambit of Article 1.1(a)(1)(iv) ASCM. In parallel with the approach taken by the CJEU and European Commission, measures could be deemed regulatory in nature—and therefore not providing a “financial contribution”—where obligations are imposed solely between private undertakings, which are not designated or controlled by the State. The scope of the term “price support” could similarly operate so as to not be “intrusive into the operation of the democratic regulatory state.” 72 In this respect, WTO panels could exclude from its purview any support deployed for the purpose of correcting existing market failures. One example of this is the energy market, which is distorted in favour of conventional energy sources and thereby prevents alternatives sources from competing effectively in the absence of government support. This approach should equally apply to the interpretation of “benefit”, while also excluding from its remit any policy aimed at compensating only for extra costs incurred and a reasonable profit margin. In doing so, panels and the Appellate Body would be aligning the WTO approach with that of the EU. The proposed approach, albeit providing more RE policy space, would still render “actionable” any subsidies which confer advantages for the mere purpose of advancing domestic protectionism. Nevertheless, despite providing a way forward, the interpretive strategy encounters the issue of altering the direction of existing case law. If it is indeed preferable to continue to develop the subsidies disciplines in a rules-based context, it is of Green World Investor, ‘Solar Energy Protectionism – Italy Joins India, Canada in formulating Domestic Content Requirements’ <http://www.greenworldinvestor.com/2011/05/10/solar-energyprotectionism-italy-joins-indiacanada-in-formulating-domestic-content-requirements/> accessed 28 September 2012. 69 Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 24. 70 Case C-279/98 PreussenElektra [2001] ECR I-2099. 71 PreussenElektra, Opinion of AG Jacobs, para 157. 72 Howse, ‘Climate Mitigation Subsidies’ (n 43) 13. 68 14 paramount importance that “sector-specific rules [be devised] for measures for which exemption … seems to be warranted.”73 (b) Expanding “Green-Light” Subsidies & GATT’s “General Exceptions” Another avenue of support for the RE sector within the WTO is to re-open and expand so-called “green-light” subsidies. This refers to a list of “non-actionable subsidies” under Article 8 ASCM, which expired five years post-Uruguay Round. 74 While ASCM justifications—including a limited form of environmental subsidy—have now expired, no notifications of a non-actionable subsidy were ever made under Article 8.3 during its operative period. 75 In light of the fact that exception under Article 8.2(c) ASCM is limited to promoting the adaptation of existing facilities to new environmental requirements, the “benefits may have seemed … to [have been] outweigh[ed] by the costs of pre-notification procedures.”76 One way to provide greater scope for exemption in the future is to adopt a rules-based approach to “green-light” subsidies within the ASCM. This is to say that exemptions would be provided on the basis of various criteria such as the type of aid–e.g. investment aid for the construction of new facilities, or operating aid to assist in lowering production costs—and maximum aid intensities. Alongside “green-light” subsidies for RE investment and production, it is also critical to accompany such enhanced policy space with rules on abuse prevention and proportionality.77 In this respect, Article 8.2(c) ASCM attempts to address such concerns through its strict eligibility criteria—restricting assistance to a one-off payment for “existing facilities” and excluding operating aid. Although Article 8.2(c) ASCM imposes strict eligibility requirements, this is a rather “blunt [and equivocal] approach” to achieving abuse prevention and proportionality—as it is achieved at the expense of creating a versatile framework for RE policy.78 The ASCM should therefore be clearer and more flexible in addressing such concerns. This may be achieved by providing detailed rules for a range of aid intensities and the calculation of eligible costs, while also requiring that all subsidies aim to contribute to enhancing sustainability objectives. To the extent that WTO Members desire the creation of greater flexibility and certainty in the RE policy-making arena, it will be equally critical that the WTO develops a framework which ensures proportionality between policy and objective. The impetus to create such a framework is likely only to materialise if the current ASCM disciplines are considered a “serious threat” to Members’ domestic RE (and related environmental) policy space.79 If Article XX GATT is indeed applicable to the ASCM, new “general exceptions” may be introduced to justify what may otherwise be objectionable RE subsidies. In addition to a general environmental exception, a specific RE exception could be included in order to ensure that sufficient coverage is provided for policies going beyond climate change mitigation—such as the increasing security of energy supply and availability of Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 25. Article 31 ASCM; Wilke (n 23) 21. 75 Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 8-9. 76 ibid 11. 77 ibid 27. 78 ibid 20. 79 Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 27. 73 74 15 affordable energy. In Europe, the European Commission has itself explicitly referred to these goals under its Environmental Aid Guidelines, as they are “not just guidelines on aid for environmental protection, but also guidelines on energy aid.”80 With regard to the proposed GATT exceptions, abuse prevention would be dealt with under the ‘chapeau’ of Article XX, which prohibits arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination and disguised restrictions on international trade. Furthermore, with respect to proportionality, it must be ensured that—like Article XX(b) on measures “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health”—the proposed exceptions are subject to the Appellate Body’s “necessity” or least restrictive means test in order for the relevant measure to be justified under Article XX. 81 Article XX would therefore provide governments with scope to deploy RE subsidies while also ensuring the WTO can scrutinise actions for arbitrariness or discrimination.82 In this respect, it will “allow some basis for action and for policing protectionism.”83 (2) NEW SUBSTANTIVE AND PROCEDURAL FRAMEWORKS (a) A WTO Agreement on (Renewable) Energy As a means of addressing current energy issues, there have been several proponents of an holistic WTO Agreement on Energy.84 This proposal is premised on the notion that, when the GATT rules were originally negotiated, issues relating to the sustainability of energy sources and the liberalisation of energy trade were not at the forefront of geopolitical discourse. On this basis, it is considered important now that the WTO “deal with energy as a distinct sector”. 85 This would be necessary to create disciplines to address the growing energy trade and the particular challenges it faces in relation to increasing demand and sustainable development. In terms of RE subsidies, Cottier et al. suggest that an Agreement on Energy would accommodate such subsidies, while also ensuring that perverse effects are avoided and harmful energy subsidies are addressed.86 The WTO could take this proposal further by creating an Agreement on RE. It is arguable that this would be more politically feasible than an Agreement on Energy, as it would deal with a discrete aspect of the energy sector. In this respect, it would be less difficult for WTO Members to find common ground in relation to RE—as a sub-sector— than in relation to the energy field as a whole. This Agreement could potentially lay the foundation for a future Agreement on Energy. However, it has been submitted that energy “does not lend itself to such sectoral negotiations” based on its form and is in need of an “integrated approach” subjecting all forms of energy to the same rules.87 Although this may be the ultimate destination, to the extent that an Agreement on Energy is politically unviable as a first step, an Agreement on RE would still represent a 80 Community Guidelines on State Aid for Environmental Protection (Environmental Aid Guidelines) (OJ C82/1, 1.4.2008), s 1; Heidenhain, European State Aid Law (Beck 2010) 270. 81 Green (n 58) 408. 82 Green (n 58) 409. 83 ibid. 84 Cottier et al (n 20). 85 ibid 212. 86 ibid 226-227. 87 ibid 221. 16 constructive development. This may then provide a future basis for transitioning towards a comprehensive sectoral agreement on energy. (b) Reshaping Notification Procedures and the Role of the Subsidies Committee Any RE-specific exemptions within the ASCM, GATT or indeed an Agreement on RE should also be coupled with new notification procedures and a revised role for the Subsidies and Countervailing Measures Committee (the “Subsidies Committee”). An improved notification system is necessary in order to provide RE policy scope and ensure that certain RE support measures are more susceptible to scrutiny for protectionism and proportionality. For WTO purposes, a dual system could be established whereby subsidies are either subject to ‘basic notification’ or ‘enhanced notification’. The type of notification could be dictated by the nature of the aid—for instance, investment or operating aid—as well as specific criteria relating to the permissible aid intensities, which could correspond to exemption requirements set within the ASCM, GATT or Agreement on RE in the future. Detailed notification could apply to more generous aid intensities and operating aid—which is more conducive to trade distortion88—and would require that notification of the aid to the Subsidies Committee be accompanied by a report explaining how the WTO Member has satisfied a proportionality assessment. In light of criticisms that the “weighing and balancing” under Article XX GATT may lean too favourably towards exemption,89 a more exacting test should be adopted. This would not only ensure that the measure was the least trade-restrictive possible, but it would also assess—similar to the EU’s Environmental Aid Guidelines90—if an overall net positive effect results from the measure. In essence, it would test whether any trade distortions are limited to the extent that they are outweighed by the aid measure’s positive effects on sustainable development. In addition to providing greater transparency through an improved notification procedure, the Subsidies Committee should also be required to approve—or provide conditional exemption to—subsidies proposed via enhanced notifications. This would arguably be a more flexible approach when compared to requiring authorisation by a subsidy management body in respect of subsidies generally.91 In the context of the WTO, the latter might be considered unduly intrusive into the sovereignty of nations and is undesirable insofar as it would involve the micromanagement of all government support programmes. 92 Furthermore, the Subsidies Committee could be mandated to provide “soft” guidance, so as to provide direction—albeit not legally binding—regarding the interpretation of the relevant “balancing test” for enhanced notifications. 88 Heidenhain (n 80) 271. Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 32-33. 90 Environmental Aid Guidelines, para 16. 91 cf Peat, ‘The Wrong Rules for the Right Energy: The WTO SCM Agreement and Subsidies for Renewable Energy’ (2012), HEI Research Paper, 21 <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1998240> accessed September 2 2012. 92 Howse, ‘Climate Mitigation Subsidies’ (n 43) 21. 89 17 V. CONCLUSION The RE sector is crucial to addressing concerns over climate change and the security of energy supply. It is therefore of quintessential importance that RE promotion policies receive the support that they require from the international trading system. In this respect, FIT programmes have become the most important instrument for levelling the playing field between RE and carbon-based energy sources. However, FIT programmes are increasingly vulnerable to future challenge in the WTO and are therefore at risk of becoming subject to considerable limitations.93 The recent WTO disputes over Ontario’s FIT programme may well be detrimental in establishing whether such programmes will become increasingly susceptible to legal action in the future. The proceedings initiated by Japan and the EU against Canada go beyond the legal status of Ontario’s domestic content requirement in the context of its FIT programme. They also engage the wider issue of whether FITs themselves constitute an actionable subsidy under WTO law. In this respect, the WTO must be receptive to the need to create a more accommodating legal framework for the deployment of RE subsidies, while also safeguarding against exempting concurrent protectionism. In order to determine the outcome of the controversy over Ontario’s domestic content requirement, the WTO panels must first determine whether the FIT programme is a subsidy under the ASCM. This paper demonstrates that FIT programmes generally take forms which satisfy the definition of subsidy under Article 1 ASCM—either constituting a “financial contribution” or “price support”. The “benefit” is especially clear, insofar as the case law and ASCM define it as the conferral of an advantage not otherwise available in the marketplace. Not only is Ontario’s FIT programme classifiable as a subsidy, but Germany’s—albeit structured differently—may also be defined as such. To the extent that FIT programmes are classifiable as subsidies, domestic policy autonomy may be at stake as RE support policies become exposed to the risk of WTO actionability. In order to render subsidies actionable, it is necessary to prove “specificity” and “adverse effects”. In light of the real prospect of WTO actionability in the future, the necessary political impetus must be garnered in order to address the unstable RE policy space provided under the existing WTO subsidies regime. The WTO has the potential to move forward in a manner that is more accommodating to RE promotion policies. This may be accomplished through interpretive strategy, the expansion of “green-light” subsidies and/or Article XX GATT exemptions, or the creation of an Agreement on RE— with the possibility of a more comprehensive sectoral agreement on energy. Irrespective of the approach adopted, it is crucial that an increase in RE policy space be accompanied by rules on abuse prevention and proportionality.94 This, in part, may be furthered by the creation of new notification procedures and a more active role for the Subsidies Committee. Ultimately, the WTO’s response to resolving the unsatisfactory policy scope for subsidies in the RE arena will be a litmus test of its ability to create an integrated trading system in a manner consistent with sustainable development objectives. 93 94 Bidgeli, ‘Incentive Schemes’ (n 36) 88. Bigdeli, ‘Resurrecting the Dead?’ (n 61) 27. 18