Collection of Case Studies

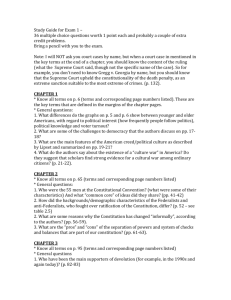

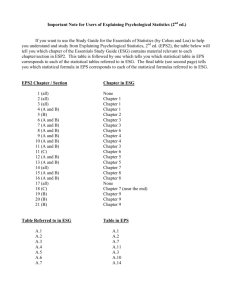

advertisement