to the 2003 RHODES REPORT

advertisement

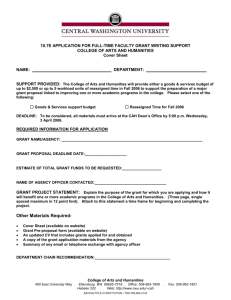

The Humanities Conference 2003 held at the University of the Aegean on the Island of Rhodes, Greece Report on the First International Conference on New Directions in the Humanities Rhodes, Greece, 2-5 July 2003 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak leads a discussion in the courtyard Hosted and organized by: The four-day conference was attended by 372 participants from 18 countries including Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Egypt, France, Greece, Hong Kong, Ireland, Japan, Jordan, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, UK, United Arab Emirates, and USA. The conference involved seven main plenary sessions and 20 parallel sessions in which 237 papers and 29 workshops were presented, as well as a host of cultural events. Since the conference, 120 papers have been submitted to be reviewed for inclusion in the International Journal of Humanities. The papers span the breadth of the disciplines that make up the humanities, linked together by the overall conference theme, ‘The Next World Order’ and the sub-themes set out below. The Humanities Conference 2003 aimed to develop an agenda for the humanities in an era otherwise dominated by scientific, technical and economic rationalisms. The conference’s conversations ranged from the broad and speculative to the microcosmic and empirical. Its over-riding concern, however, was to redefine the human and mount a case for the humanities. At a time when the dominant rationalisms are running a course that often seems to be drawing them towards less than satisfactory ends, this conference reopened the question of the human for highly pragmatic as well as redemptory reasons. To the world outside of education and academe, the humanities seems at best ephemeral, and at worst esoteric. They appear to be of less significance and practical ‘value’ than the domains of economics, technology and science. This conference series examines, and exemplifies, the inherent worth of the humanities. Papers ranged across a wide range of disciplines, including Anthropology, Archaeology, Classics, Communication, English, Fine Arts, Geography, Government, History, Journalism, Languages, Linguistics, Literature, Media Studies, Philosophy, Politics, Sociology and Religion. Central conference considerations included: the dynamics of identity and belonging; governance and politics in a time of globalism and multiculturalism; and the purpose of the humanities in an era of contested ends. Theme 1: Globalism and Identity Formation The dynamics of identity and belonging. Cosmopolitanism, globalisation and backlash. The humanities and the construction of place First nations and indigenous peoples in first, third and other worlds. Human movement and its consequences: immigration, refugees, diaspora, minorities. Ecological sustainability, cultural sustainability, human sustainability. Homo faber: the human faces of technology. Global/local, universal/particular: discerning boundaries. Differences: gender, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, race, class. Theme 2: The Modern and the Postmodern Defining the modern against its ‘others’. The postmodern turn. Nationalism, ethnonationalism, xenophobia, racism, genocide: the ‘ancient’ and the modern. Governance and politics in a time of globalism and multiculturalism. The causes and effects of war. Metropolis: the past and future of urbanism. Geographies of the non-urban and remote in the era of total globalisation. Theme 3: The ‘Human’ of the Humanities The human, the humanist, the humanities. What is history? The philosophy of ends or the end of philosophy? Anthropology, archaeology and their ‘others’. The work of art in an age of mechanical reproduction. Literary-critical: changing the focal points. Ways of meaning: languages, linguistics, semiotics. Theme 4: Future Humanities, Future Human Science confronts humanity. Humanities teaching in higher education: fresh approaches and future prospects. Schooling humanities: introducing history, social studies, philosophy, language, literature and the humanities to children. Technologies in and for the humanities. The purpose of the humanities in an era of contested ends. The humanities in the ‘culture wars’: questions of ‘political correctness’ and the cultural ‘canon’. Keynote speakers The opening keynote address was presented by Giorgos Tsiakalos, Professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and President of the Nicos Poulantzas Society. Focusing on the relationship between the humanities and the natural sciences, he reminded the audience that there has been a long interest in exploring the biological bases of human behaviour, both from within the sciences and within the humanities. While scientists do not always know how their work will be taken up in relation to social issues, humanities scholars have been more attuned to the social impacts of the sciences and humanisitic enquiry. He pointed as an example to American sociobiologist E.O. Wilson’s new book, which tries to bring together social science, humanities, biology and other sciences. Wilson argues that xenophobia is natural, yet it was honoured by the Humanities Association and the Philosophy Association in the USA in 1999. Because such work can quickly make its way into mainstream debates, law and politics it is dangerous and needs to be countered by the humanities. The humanities urgently need to address the new synthesis of biology and humanism in the form of biotechnology, which has the capacity to extend scienticly-produced risks across time and space as never before. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak began by reminding the conference that one of the most significant applications of sociobiology has been to reframe women’s experience in terms of masculine scientific knowledge systems. The humanities, she proposed, do not derive their power from a privileged access to some essential humanness, but from their capacity to train the imagination. ‘Reading the literary’, she stated, ‘exercises the imagination to go towards the other’. Instruction in the humanities in themselves will not lead to ‘good’ politics or instill ‘good’ values, since these things are invariably contested and need to be taught self-consciously. She proposes expanding comparative literary studies, which she believes is overly Eurocentric, by integrating such studies more in the field of area studies. She scoffed at a claim made by Derrida and Habermas in May 2003 that Europe had developed a reflexivity about international power (that was presumably lacking in the USA) because of its experience of colonialism. European humanities scholars should not become so complacent about their own countries’ role in world affairs, she warned, suggesting that such smugness paralled the debates underway between the EU and the US as to who is best at ‘the empire game’. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak is Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where she teaches English and the Politics of Culture. Nikos Papastergiadis discussed how humanities scholars in Australia had been sidelined during ‘the new authoritanarianism’. While the Australian government was turning away refugees and claiming that they posed a risk to national security in the wake of September 11, humanist critics were being criticised for their ‘blackarmband view of history’ by the government and conservative commentators. As public servants were silenced, a battle was played out in the domestic media and the government largely succeeded in depersonalising refugees as ‘asylum seekers’, ‘queue-jumpers’, ‘potential terrorists’ and ‘potentially-diseased’. Without independent access to the refugees or their experience, the Australian public was unable to ‘imagine the other’ in ways that would foster humanistic compassion and understanding. Nikos is Senior Lecturer and Deputy Director of the Australian Centre at the University of Melbourne. Paul James reminded the conference that even George W. Bush uses the language of reciprocity, god and humanity, demonstrating the ways in which the humanities have been taken up, and emptied out, by spin doctors of new forms of authoritarianism. Because of the resulting hollowness of many core concepts we can no longer rely on the humanities to deliver positive social values on their own. After the Second World War, he argued, the humanities dissolved into empiricism on the one hand and posmodernism on the other, and neither of these strains has been able to provide adequate responses to three totalising transformations that have occurred during this period: militarism; capitalism; communications and; technoscience. Professor James is Director of the Globalism Institute at RMIT University, Melbourne. Mary Kalantzis observed that all governments are dealing with growing cultural diversity, and corresponding calls for recognition and self-determination. In this context, she called for governments to advocate civic pluralism and abandon efforts at cultural formation conceived of in terms of national identity. States should instead create opportunities for expression, recognition and access to resources by a diverse range of groups. States that don’t respond to diversity favourably face growing levels of social conflict, and often respond to the challenges posed by diversity repressively. Mary Kalantzis is Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Education, Language and Community Services at RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Juliet Mitchell’s paper, ‘A thought on war and the brotherhood of man’, began by noting that the humanities had split into two streams, one text-based and the other observational, and these need to keep in touch with one another. She then related the psychoanalytic concern with hysteria, to the invasion of Iraq. She recounted how from the late Nineteenth Century men suffering from the symptoms of hysteria were described as having ‘traumatic neurosis’ and that such diagnoses were commonly ascribed to men who survived the First World War. The hysteric becomes fixated on early childhood trauma, which resurfaces throughout life as new traumatic episodes take place. The people who experienced the recent bombing in Baghdad and other parts of Iraq will carry that trauma with them into old age. She extended this in the last section of her paper with a discussion of sibling rivalry (implicitly reflecting on the relationship between those imperial siblings, the UK and USA). Juliet Mitchel is Professor of Psychoanalysis and Gender Studies and Head of Department in Social and Political Sciences at the University of Cambridge. Tom Nairn suggested that to talk of human nature a few years ago was to put oneself on the early retirement list. It has now become so fashionable that Francis Fukuyama has devoted a recent book to the topic, The Posthuman Future. Believeing that it is important to know your enemies, Nairn spelled out the main themes of Fukuyama’s book. Fukuyama argues that we cannot do without the notion of a core human nature, which he refers to as the ‘x factor’, and posits the existence of a ‘clear red line’ that (following Neitzche) he believes distinguishes humans from animals. Fukuyama argues that we must use the state to stop blurring this line. He claims to be defending the humanities, but ignores a huge body of literature over the past century on this topic, showing in practice little interest in the body of knowledge that has been accumulated. While Fukuyama is vague about the characterisitcs of this essential human nature, he does posit that equality is a key part of the ‘x factor’. Nairn warns about the political consequences of such essentialist thinking coming out of the USA at present, and argues that the humanities need to engage in such debates, and one immediate step could be to suggest that diversity should be included as a key feature of any reconception of human nature. Tom Nairn is Professor of Nationalism and Cultural Diversity in the Globalism Institute at RMIT University in Melbourne. To mark the launch of the second edition of Tom Nairn’s The Breakup of Britain, Joe Cox spoke about the importance the book had on her and her colleagues. Performance by the Aegean University Theatrical Group Folkloric Dance Performance, Dimoglou Theatre Further Details If you would like to know more about this conference, see The Humanities Conference 2003 site (http://humanitiesconference.com/), where you can subscribe to The Humanities Conference Newsletter. For any other inquiries, please contact Selena Papps at Common Ground Conferences (selena.papps@commongroundconferences.com) or Christopher Ziguras at the RMIT Globalism Institute (christopher.ziguras@rmit.edu.au). Common Ground Conferences PO Box 486 Altona 3018 VIC TEL: 03 9398 8000 FAX: 03 9398 8088