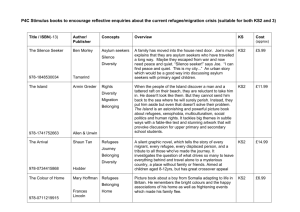

Beyond The Pale: - Child Migration

advertisement