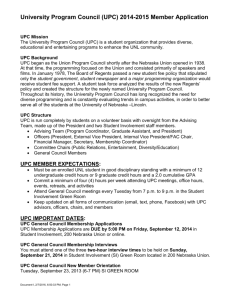

here

advertisement