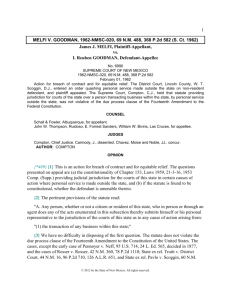

Civil Procedure Quiz

advertisement