Northfield Township English/Language Arts Articulation Report

Susan Levine-Kelley

Edward Solis

Helene Spak

Cathy Terdich

February 2010

1

INTRODUCTION

RATIONALE

The teaching of the humanities is vital in the twenty-first century. Today, students’ attentions are

pulled in multiple directions; the language arts give us the opportunity to bring focus and passion

to students’ lives. The language skills of reading fiction and non-fiction, writing, vocabulary,

speaking and listening are at the very foundation of all education and at the center of language

arts/English instruction. Literature gives each of us the opportunity to stand in the shoes of

another person, to develop empathy and understand the world in a way that would not otherwise

be possible. The ability to express ourselves in an articulate, thoughtful, logical way requires the

critical thinking and analytical skills that are called upon every day in the classrooms of our

Northfield Township middle schools and high schools.

The Northfield Township Language Arts/English Articulation process has given the teachers of

our Township the chance to assess our curriculum and practice to ensure that high quality

instruction continues and improves as the challenges of the twenty-first century continue to

emerge. To accomplish this charge, the exploration focused on three questions:

What do students need to know and be able to do as a result of the study in English to be

successful in the emerging and changing global society?

Where is current curriculum and instructional practice in English in the Township in

terms of meeting those standards?

What recommendations can be made after analysis of research and current Township

curriculum and instructional practices?

To begin answering these questions the committee used four documents as our foundation:

Adolescents and Literacy: Reading for the 21st Century by the Alliance for Excellent Education,

To Read or Not to Read: A Question of National Consequence by the National Endowment of the

Arts and Learning for the 21st Century by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills. The committee

also looked for guidance in National Council of Teachers of English/International Reading

Association Standards for the Language Arts, the College Board College Readiness Standards

and the Illinois Assessment Framework.

The foundation of these documents led the committee to further best practice research in (1)

reading and literature and (2) communication including writing, listening, speaking, and

vocabulary. The committee made the decision to divide the research in each area into three

sections: content, instruction and assessment. Technology with attention to twenty-first century

skills was a segment for all areas in the study. The research is summarized below.

READING

Literature arts educators must help students approach the job of constructing meaning while

reading. Teachers must explicitly point out that people read for different purposes. Helping

students to acknowledge that reading for pleasure can be different than reading for academic

2

purposes might assist in managing their expectations. This distinction assists students in

realizing that every reading task involves a different level of critical engagement.

Teachers must explicitly teach students the unique nature of the varied types of texts they will

encounter, and must therefore present various genres to students. Teachers are thus able to

inform students’ pre-reading expectations and their choices of strategic approaches during the

reading process. It is also important to note that student access to a variety and volume of texts

is ever-expanding in the 21st century.

Educators must also acknowledge the implications of what they choose to ask students to read.

Teachers must ask, when evaluating the scope of chosen texts, who is doing the writing? Who is

left out? Who is included and who is not? As anti-racist educators Emily Style and Enid Lee

point out, teachers have an obligation to present a multicultural versus mono-cultural selection of

texts, to widen student perspectives with “windows” into less familiar territory, and at the same

time, to “mirror” familiar aspects of their own experiences.

Because reading is a process of constructing meaning through interactions between readers and

writers, strategies that promote this interaction enhance reading comprehension. Reading and

writing, furthermore, are reciprocal processes and should not be separated (Rief 2007). During

instruction, students both read and produce texts (Smagorinsky 2008). People who read get

better at writing; people who write get better at reading (NCTE 2004). Reading allows one to

synthesize prior knowledge with new knowledge; writing allows one to create texts that reflect

that knowledge (Smagorinsky 2008). The use of patterns in both reading and writing helps

students to comprehend and produce ideas more efficiently (Weinstein 2001).

Similarly, vocabulary plays an important part in reading comprehension. As early as 1924,

researchers noted that growth in reading meant continuous growth in word knowledge (Whipple

1925). Direct vocabulary instruction improves comprehension, but prior knowledge and

experience support increased vocabulary knowledge (Allen 1999).

Assessments in reading need to have a purpose and must be construed in a way that makes it so

that a student has a way out and doesn’t feel trapped. Throughout the school year, students’

reading processes should be assessed in an ongoing manner through meaningful formative and

summative assessments. All assessments should have a purpose.

“Teachers who know their students and the curriculum well and use this knowledge to diversify

instruction to meet students’ needs enhance the process of learning to read” (Wolf 1988). In

order to get a true assessment of where a student starts and ends throughout the year, teachers

need to ask: How do we know a student individually in terms of his/her reading skills? What

can we do to get to know our students’ reading abilities, especially when we have many kids?

How do we assess them so that the valuable information that we have gained can be passed from

one teacher to another?

3

Ultimately, as teachers instruct students in reading and literature, they need to make assessments

meaningful to the teacher and the student. There is a fluid relationship between curriculum,

instruction and assessment. In the best classrooms, it can be difficult to distinguish between

instruction and assessment (Cobb 2003).

In order to modify curricula in a meaningful way, teachers need to understand the reason for and

behind formal assessments. Knowing how to apply the results will improve instruction in

reading across the board. “Assessments should not mark the end of learning but rather a

checking point for the level of learning, as well as a reflection of what needs to happen

next”(Cobb 2003). The most effective way to guide instruction, curriculum and assessment is

for both administrators and teachers to sit down and talk about the student work. The students

should have multiple ways and times to show their various amounts of knowledge. Then the

follow up with the students can be effective, meaningful, and have a lasting impact.

According to Buly and Valencia in “Are Assessment Data Really Driving Middle School

Reading Instruction?”, “teachers often assume students not performing at grade level on

standardized tests of reading are demonstrating a lack of ability in relation to early literacy skillsregardless of the skills being assessed…” Struggling readers are not being provided with books

to read” (Wolf 1988).

Assessment is two-fold in reading and literature. While teachers are assessing the students, the

students should also be assessing the material. Through the active reading strategies, small

group and online discussion, the students can flush out a new meaning of the material.

WRITING

As noted above, reading and writing inextricably related. Writing is a fundamental human tool

that connects human beings to their past and to each other. Schools must provide students with

this tool so they will learn to successfully formulate thoughts and articulate ideas. Current

research about writing has identified a number of best practices for writing instruction.

The National Council of Teachers of English, (NCTE) believes that everyone can write, that

teachers can provide direction for the teaching of writing, and that writing needs to be grounded

in real-life experiences and is used for a variety of purposes (NCTE 2004, 2008). Teachers must

tailor lessons according to students’ “strengths, interests, and needs” (Rief 2007), provide

meaningful writing experiences and instruction, practice the craft of writing themselves (Murray

2007), and sometimes even do the assignment themselves (Smagorinsky 2008). Students need

mentor texts to provide models for good writing, feedback about their writing, and time for

reflection about writing (Atwell 1987 and Fletcher 2007). They also need exposure to and

comfort with a variety of writing genres: journal entries, responses to literature or curricular

concepts, poetry, editorials, fiction, etc. (Romano 2007).

4

Teachers must also consider various factors about students when they teach writing. For

example, Fletcher (2007) found that boys tend to avoid writing, but that when they do write, they

tend to write more for each other as an audience. Writing by boys also reflects action, violence

(intended as humor), satire and parody. Girls, on the other hand, avoid writing less than boys do,

perceive writing differently, and focus more on nouns in their writing (Fletcher 2007).

Smagorinsky (2008) finds that boys tend to relate to a more authoritative style of knowledge that

is competitive, aggressive, and autonomous, while girls are more “connected” in their learning,

thus being more tentative, nurturing, cohesive, collaborative, and situational (Smagorinsky

2008). In creating writing curricula, Smagorinsky advises teachers to consider the influences of

culture, tradition, race, community values, demographics, personal interests, and the

psychological, developmental, and circumstantial needs of students. As teachers select content

for instruction and develop English curricula, teachers must weigh the merits of a traditional

versus liberal canon of literature, the literary value of their selections, a variety of textual forms

(short story, novel, play, film, drama, dance, art, etc.), the homogeneous versus heterogeneous

composition of classes, and the propriety of skills and content for the age, school, and

community. Literature should reflect authorship that balances men, women, various races,

traditions, and cultures and include canon as well as non-canon works. Curricular design should

reflect the psychology of human development, cultural significance, literary significance, civic

awareness, current social problems, the preparation for future needs, and finally, the alignment

with professional teaching standards in its content (Smagorinsky 2008).

Writing, furthermore, is not a “formulaic set of steps” but rather a recursive process that evolves

and continues as a lifelong process of “refining” skills (NCTE 2004, 2008). Writers must

collect, focus, order, develop, and clarify ideas as well as interact with each other during writing

(Murray 1987). Revision, discussion, and feedback from peers are productive means by which

students may sort and clarify their thoughts (Weinstein 2001). Weinstein cautions against

outlines that lead to flat and formulaic writing if students merely fill in blanks; good writing

depends on the flow of ideas, so first drafts do not need perfect organization or structure. Free

writing, in which students write continuously without breaks for ten minutes, promotes writing

fluency and thought (Weinstein 2001). Smagorinsky (2008) finds that students benefit from

alternatives and options, from both conventional and unconventional writing assignments.

During the process of writing, students may engage in brainstorming, outlining, drafting, taking

notes, and getting both feedback and recommendations from peers (Smagorinsky 2008).

Students also benefit from structured mini-lessons, small group instruction, and individual

teaching with conferences (Ray 2001); Atwell maintains writers need individual topics and

consistent writing time. Once drafting is complete, writers should reread their work again three

different times: for meaning, order, and voice.

Voice in writing must be developed by each writer, and because writing is closely related to

talking, discussion enhances development of voice (NCTE 2004, 2008). Students rehearse this

relationship through telling stories, explaining, giving oral directions, having writing

5

conferences, and speculating about people and things. This rehearsal process continues as

students talk about their writing to themselves and others, thus helping writers to develop voice

as an integral part of their writing (NCTE 2004, 2008).

Writing is similarly a thinking tool that helps students to generate ideas, solve problems, identify

issues, construct questions, try new ideas, and reconsider previous ideas (NCTE 2004). Writers

must decide whether or not they want to be honest as they share their thoughts through writing.

Weinstein (2001) maintains that it is more important for students to value writing as a thinking

tool rather than a product with absolute answers.

Writing, moreover, has a multitude of purposes and audiences and is used for civic, social,

personal, spiritual, professional, academic, relational, and aesthetic communications (NCTE

2004). Teachers must encourage students to remember their audience as they write for personal

growth, expression and reflection, participate in democratic processes, create aesthetic and

artistic forms of writing, and produce academic texts suited to various disciplines. Such writing

may range from casual draft e-mails to carefully crafted legal documents or research papers

(NCTE 2004). Smagorisnky observes that writing may also be exploratory, affective,

collaborative, or creative (2008). Exploratory writing allows for alternatives and options that

demonstrate new products and new learning without the pressure of a final draft; affective and

collaborative writing may include affective response journals, student-generated discussions,

narratives, multi-genre products, or interpretive texts for students. Creative writing may include

poetry, fiction, or drama.

Research concurs with the NCTE position that conventions must be followed within writing

(NCTE 2004). Atwell (1987) maintains that writers learn mechanics and writing strategies

through the context of their own writing. Weinstein (2001) believes that grammar errors pose

problems when they create confusion about meaning, affect the writer’s credibility about the

topic, or distract the reader from the meaning of content. Smagorinsky (2008) argues that

“rambling syntax” and deviations from standard English both limit students’ future success and

handicap them on standardized tests. Moreover, one hundred years of grammar research

supports the position that grammar must not be taught in isolation but rather within the context of

writing (Hillocks 1986; Weaver 1996; Smagorinsky 2008). Grammar concepts should be taught

slowly and thoroughly according to what is correct in specific situations and what will result in

better sentence structure (Pool, 1954 as cited by Smagorinsky 2008 p 165). Teachers should also

target language issues that affect status, use corrective terminology for text purposes, and focus

instruction on recurring errors (Smagorinsky 2008). Finally, teachers should be aware that some

errors may be developmental (Shaughnessey, 1977 as cited by Smagorinsky 2008), and may be

signs of growth (Rose 1990, p 188-189 as cited by Weinstein 2001, p 75).

Research further supports that writing is a social activity in which writers talk individually about

their writing and with others in class (NCTE 2004). Smagorinsky’s (2008) approach to

scaffolding requires social interaction between the teacher who introduces a concept through

6

accessible material and students who learn the concept in small groups. Eventually, students

move toward independence. Weinstein concurs that students benefit from small group work and

scaffolding of concepts (2001). Social interaction may occur at any time during the writing

process and it may be corrective, constructive, or supportive. Small groups create valuable

feedback that a student may apply to both critical reading of his or others’ papers (Smagorinsky

2008). Because writing is social, NCTE also maintains that writers must know their audience and

that this knowledge must direct the writer’s content, tone, and voice.

The assessment of writing can take many forms, from conventional to alternative (Smagorinsky

2008), or formal to informal. Casey (2008) laments the practice in some schools that lessons to

raise test scores take priority over the use of computers for writing instruction. Effective

evaluation should “highlight the strengths of process, content, and conventions, and provide

techniques to strengthen the weaknesses.”(Rief 2007, p. 189-208). Smagorinsky believes that

the challenge is to create assessments for students with different needs, backgrounds, and skills

(2008). Ray (2001) suggests evaluation take place at the beginning, middle, and end of

instruction and may include items such as portfolios, reflections, extended definitions, analytical

essays, multi-media projects, literary analyses, argumentation, and research. Smagorinsky

(2008) recommends that writing assessment include the following: description of general task;

set of parameters for producing text; how it will be evaluated; teacher goals; what the teacher

needs to teach students how to do; and criteria to guide assessment. One such guide is the rubric,

which should be based on the following questions:

“What might students learn and how do I know?

What conventions are necessary for this assignment?

What level of detail is necessary?

What degree of cohesion should the student achieve?

To what degree has the student met each point in the assignment?” (Smagorinsky

2008, 102).

Although Alfie Kohn (2006) as cited by Smagorinsky (2008) cautions that rubrics can turn

teachers into “grading machines” that promote standardization, Smagorinsky (2008) believes that

good rubrics can lead to richer and more sympathetic readings of text, using the analogy of a

builder who follows the code but deviates as needed.

Ray (2001) recommends that teachers use a variety of assessment tools for students. Assessment

should focus on both the learning process and products created by the student. These student

artifacts should be accompanied by questions that ask about the student’s history with writing

experiences, actions taken as a writer, decisions made during the writing process, and selfevaluation about growth and process. Students might self-assess their use of independent writing

time, strategies to support independent writing, productive peer interactions, and engagement

with all steps of the writing process. Artifacts thus support student assessment.

7

Technology plays an essential role in reading and writing and is a vital part of students’ daily

lives (Casey 2008). English teachers are therefore obligated to merge their knowledge of reading

and writing with what students know about technology (Kajder 2007). Technology, however,

must be used in the pursuit of learning (Casey 2008). Smagorinsky (2008) says that everything

students read or produce is a tool for learning and that instruments for learning may be languagebased, non-verbal, or artistic devices that allow for the integration of all forms of visual, artistic,

or performance-based media and technology in the English classroom.

Advances in technology and the creation of new electronic media will pose new advantages and

challenges for literacy, reading, and writing. These developments will create new areas of

research with future implications for teaching.

COMMUNICATION

The integration of speaking and listening instruction is seminal to the development a highlyskilled, contributing citizen. As early as 1973, the National Council of Teachers of English

(NCTE) demonstrated support for explicit instruction and assessment on a national level.

Research in the twenty-first century literacies supports the need to teach varied speaking and

listening skills including traditional public speaking skills, collaborative group skills, and the

proficient use of technology tools. This developmental instruction needs to focus on process and

preparation as much on the product. As in writing, assessments should take many forms:

formative and summative; formal and informal; teacher, peer, and self. Rubrics aid in skill focus,

ensuring that the assessment reflects instruction.

VOCABULARY

Vocabulary instruction strengthens learning in all areas. Vocabulary refers to words that are used

in speech and print to communicate. Vocabulary can be divided into two types: oral vocabulary,

the words used in speaking or recognized in listening, and reading vocabulary, the words used in

print (National Institute for Literacy 2007). Good readers have a wide range of oral and print

vocabulary; often, word schema results from extensive and repeated exposure to words through

speaking and reading. Without knowing what words mean, readers cannot understand what they

read (NIL 2006). One of the most important findings in the research on vocabulary indicates the

strong connection between vocabulary knowledge of readers and their ability to understand what

they read (Blachowicz, C. and Peter Fisher 2001). According to research by the National

Reading Panel, vocabulary knowledge is the single most important factor contributing to reading

comprehension.

Pre-teaching the meaning of vocabulary words before students encounter them in text facilitates

reading and understanding. Without knowing what words mean, readers cannot understand what

they are reading (National Institute for Literacy 2007). Once vocabulary words have been

introduced, teachers need to continue to expose students to these same words so that they

become part of the students’ oral and written vocabulary (National Institute for Literacy 2007).

8

In classrooms where vocabulary growth, awareness of new words, and a curiosity of word

learning are promoted, vocabulary extends beyond the lesson or the classroom. Students

increase their interest in word histories, play with words, and use new words in speech and

writing.

Research suggests that there is no single best way to teach vocabulary. Yet, the National

Reading Panel (2000) found that vocabulary is learned both indirectly and directly and that

“dependence on only one instructional method does not result in optimal growth” (Rasinski, et

al. 2007). Vocabulary learning can occur in a variety of ways, not always as teacher directed

learning (Blachowicz, C. and Peter Fisher 2001). Although many vocabulary strategies have

been effective in improving adolescent literacy, using a variety of techniques is most effective.

Vocabulary instruction leads to gains in comprehension, but the methods must be appropriate to

the age and ability of the reader.

For teaching new vocabulary words, independent word learning strategies, such as dictionary use

and context clues, are useful. Research also suggests three key methods for vocabulary growth:

wide reading; direct, explicit instruction of words and word strategies; and a learning

environment that fosters word knowledge (Yopp and Yopp 2007).

Research supports the use of direct, explicit, systematic instruction for teaching vocabulary.

Lessons should be fast-paced, brief, multi-sensory, and interactive so that students can see, write,

and hear new words. Explicit vocabulary instruction can occur through specific word instruction

and word learning strategies that require active engagement with words and should focus on

important words, key words, useful words, and difficult words. Explicit instruction also involves

explaining word meanings and modeling the use of difficult content-area vocabulary in sentences

relevant to the subject area; guiding students to practice using vocabulary in different sentences

and contexts and giving feedback; providing time for practice using the new vocabulary; and

repeating the instructional steps until students are able to use the vocabulary independently in

their reading, writing, and speaking.

To learn and retain new words and concepts, students need to connect these words and concepts

to what they already know. They also need repeated exposure to words and concepts and

opportunities to practice them in different contexts. Twelve word repetitions, for example, are

often needed for retention. Students learn the meanings of words indirectly through everyday

experiences with oral and written language. Students do so by engaging in oral language, by

listening to adults read, and by reading extensively themselves.

Because students also learn most new words incidentally through wide reading, teachers must

help students learn strategies for vocabulary development. Research suggests that key strategies

include the efficient use of the dictionary, the use of context clues, and the knowledge of word

parts such as prefixes, roots, suffixes, and compounds to unlock meaning. Students need explicit

instruction and modeling to learn how to look up the meanings of unfamiliar words and how to

decide which definition is the most appropriate within context. Teaching students strategies for

using context clues to determine meaning is a significant strategy. Context clues include

9

definitions, examples, and restatement. Modeling and teaching students how to use information

about word parts can be extremely valuable in vocabulary development. Because much of the

English language comes from Greek and Latin prefixes, roots, and suffixes, it has been proven

that knowledge of these roots often gives clues to word meanings. This is especially true in

science because the terms are multi-syllabic. Thus, it would be good to teach derivatives.

Discussion is an important teaching strategy to improve vocabulary. From discussion, students

can understand a word’s meaning from pieces of knowledge in a class discussion; good

discussions can clarify meaning. Not all words, however, need discussion; teachers should

review and focus on the terms that are needed to understand a story.

All content areas have specific vocabularies; teachers, however, cannot teach all the words in a

text which students need to know. Teachers should teach several words well per week so that the

words and their meanings are retained; such time should be spent on direct vocabulary

instruction. Students may also understand much of the text without knowing the meaning of

every text word. Focus should be on important words, useful words, and difficult words. Words

with multiple meaning should be directly and explicitly taught because they are particularly

challenging for students. Similarly, idiomatic expressions can be difficult for students,

especially ELL students, and often need to be explained in order to be understood (National

Reading Panel 2000). Students remember more when they relate new information to known

information.

Indirect vocabulary learning occurs in many ways. Regardless of grade, students learn

vocabulary from hearing text read aloud; students learn words from hearing a variety of texts

read to them. Reading aloud works best when teachers discuss the selection before, during, and

after reading. Teachers need to discuss the new vocabulary and concepts and relate new words

to prior experiences and concepts. Students should also be encouraged to read independently and

extensively in order to learn vocabulary indirectly. In addition, teachers need to share their love

of words with their students. In all vocabulary learning strategies, modeling, guided practice,

and both using and applying the strategy independently are essential for increasing vocabulary.

Vocabulary knowledge can be assessed in many ways. Vocabulary tests can be formal or

standardized, or less formal teacher-made tests designed specifically for individual classes and

content areas (Kruidenier 2002).

In an effort to successfully assess vocabulary knowledge, a distinction needs to be made between

receptive and expressive vocabularies. A student’s receptive vocabulary includes words he/she

can recognize; whereas a student’s expressive vocabulary includes words he/she can use

correctly and with confidence (Kinsella 2008).

Many formats for assessment like simple matching, writing a definition or using the word in an

original sentence reveal little about a student’s actual word mastery; teachers should refrain from

designing such assessments. Because assessing a student’s vocabulary is quite difficult and no

10

single measure or strategy is enough, both standardized and informal inventories can prove

useful (Joshi 2005).

Research shows that vocabulary instruction using computer technology can be useful for

struggling readers who need additional vocabulary practice. Activities such as engaging in

computer games, using hyperlinks where students click on words and icons to add depth to

vocabulary, utilizing online dictionaries rather than print dictionaries, finding content websites

where students can access information, and using other high interest computer programs are

extremely effective in vocabulary instruction. In recent research studies, the use of computers in

instruction was found to be more effective than traditional methods; computer technology is

clearly seen as an aid in instruction.

REPORT OVERVIEW

This report examines the Language Arts/English curricula in grades 6-10 throughout the

Northfield Township and seeks to identify a core set of skills and content knowledge (aligned

with Illinois State Standards) that students should attain in the core areas of literature/reading,

writing, speaking and listening, and vocabulary with an attention to a successful, smooth move

from 8th to 9th grade. This report is also interactive with the Township Wiki,

http://northfieldtownshipschools.pbworks.com/ and should be referenced when sections of the

report call for its use.

REPORT STRUCTURE

This report is organized into several numbered sections Section 1: Methodology; Section 2:

Teaching Survey; Section 3: Skills Continuum; Section 4: Content & State Standards;

Section 5: Recommendations and Section 6: Conclusions. The Methodology section describes

the committee formation, lists the essential questions guiding the report, and briefly describes the

meeting agendas and actions of the Northfield Township Language Arts/English Articulation

Committee used to generate this report. The Teaching Survey section details the methods by

which data was collected from all Township Language Arts/English teachers via an online

survey and lists the results of the survey as findings. The complete survey and survey results are

provided in Appendices II and III. The Skills Continuums are the products of articulation

meetings with middle school and high school teachers.

11

SECTION ONE: METHODOLOGY

COMMITTEE FORMATION

On December 14, 2007, Ed Solis and Susan Levine-Kelley and the English Department

Instructional Supervisors at Glenbrook North High School and Glenbrook South High School

respectively, Cathy Terdich, English teacher at Field Middle School, Northbrook School District

31, and Helene Spak, Middle School Reading/Language Arts Coordinator for Northbrook School

District 27, met to discuss the proposed Township Curriculum Study for English. At this

meeting, the members reviewed the purpose of the study and discussed the essential questions

developed by the Township Curriculum Directors. The purpose of the study was to provide a

venue for the Township Districts to collaboratively explore current research in the context of

current curricular practice. In addition, the committee was asked to answer essential questions

prepared by the Township Curriculum Directors. A timeline was developed to guide the process

of the study with an initial planning phase, a research phase, a data collection phase, a data

analysis phase, and a time to disseminate the information to the Township Curriculum Directors.

The Township Curriculum Directors recommended English teachers from each district to

participate on the committee. Initially, the committee consisted of twelve teachers with at least

one representative from each public high school, the sender schools, and North Shore Academy.

No representatives from the Township parochial schools participated on the committee. Please

see Appendix 1 for a list of committee members.

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

Several essential questions were developed to guide the process and to analyze and collect data.

These questions were formulated based on the input from the Township Curriculum Directors

and Susan-Levine Kelly, Ed Solis, Cathy Terdich, and Helene Spak. The guiding questions used

in this report are:

What do students need to know and be able to do as a result of the study in English to be

successful in the emerging and changing global society?

Where is current curriculum and instructional practice in English in the Township in

terms of meeting those standards?

What recommendations can be made after analysis of research and current Township

curriculum and instructional practices?

MEETINGS

Members of the English Articulation committee met on February 5, 2008, on June 24, 2008,

June 26, 2008, and October 6, 2008. At the first committee meeting on February 5, 2008, the

goals and objectives of the study were shared, the essential questions were reviewed, and the

proposed parameters of the study were presented. The committee also determined the need for a

method for data analysis and the need for the determination of the standards to be used. Three

articles were disseminated for discussion at the June 24 meeting. These articles included To

Read or Not to Read, November, 2007 from the National Endowment for the Arts; Adolescents

12

and Literacy, Reading for the 21st Century, November, 2003, by Alliance for Excellent

Education; and Learning for the 21st Century from The Partnership for 21st Century Skills.

At the June 24, 2008 meeting, the goals, framework, and timeline for the articulation study were

reviewed. The three assigned articles were discussed to develop baseline knowledge, to relate to

the township districts’ philosophies, to share common language, and to forecast implications for

the study. Also, the committee members agreed on the following parameters for the study:

reading/literature, writing, vocabulary, 21st century skills, visual literacy, critical thinking, and

communication, which include speaking and listening. Each teacher selected one of the

parameters of the study for individual or group research which would reflect current research and

best practice on the topic. Focus for each topic would include content, instruction/process,

assessment, and technology. At that meeting, it also was decided that the Illinois State Standards

and the IRA/NCTE Standards for English Language Arts would be used for research purposes,

data collection, and data analysis.

At the June 26, meeting the teachers gathered and synthesized the research on their specific

topic. The research would be used in developing questions for a Township survey. Because we

would not meet again until the fall, the teachers were responsible for continuing their research

over the summer and through the first month of school.

At the October 6, meeting the committee members reported their progress and findings on the

research topics, and a wiki was created for the group to share their research. In addition, the

members were asked to finalize their questions based on the research to be used in a Township

survey for all English teachers grades six through twelve.

Between October and April, the committee members completed their research and developed the

survey questions. In April, the four committee chairs collated and reviewed the survey

questions. Then, Susan Levine Kelley finalized all the questions to be used from each of the

research topics. The survey was disseminated to the Township 6th through 12th grade English

teachers. Next, the committee chairs reviewed the survey data in light of Illinois State Standards

and the NCTE/IRA Standards to determine findings and trends.

During that time, Ed Solis contacted Carol Jago, incoming president of National Council of

Teachers of English (NCTE), who was moving from California to Chicago. She was available to

speak to the Township English teachers on October 9, 2009. The four committee chairs met

several times to plan for a professional learning experience that would be meaningful to 6th

through 12th grade Township English teachers.

More than one-hundred Township English teachers attended the first Professional Learning day.

Based on the survey findings, Carol discussed Reading in the 21st Century. At this time, the

teachers were informed of the work of the Township Curriculum Study for English and the

survey results were shared. In addition, at the morning session, teachers from all of the feeder

schools and the high schools met in small groups to discuss a variety of topics gleaned from the

survey findings. The topics included: Supporting Reading Instruction in the 21st Century; Active

Reading; Differentiated Reading Instruction; Formative Reading Assessments in Reading and

Literature Study; What Books Should We Teach; Instructional Reading Strategies for Fiction and

Non-Fiction; and Teaching Issues of Race, Class, and Gender in the 21st Century. Lunch was

13

provided for the teachers. The eighth and ninth grade teachers only met in the afternoon to

discuss focus on Bridging the Gaps and Future Collaboration. Groups met to review and update

the 6-12 research continuum; to share the various writing programs and writing strategies used in

the Township; to review and update the 6-12 novel, short stories, and films used; to discuss the

writing products, including genres taught, for what purpose and audience; to share the support

systems for struggling learners; and to examine the use of technology across the Township.

Based on the evaluations and feedback, the Township teachers valued the day and were looking

forward to future Township professional learning opportunities.

SECTION TWO: TEACHING METHODOLOGY

DATA COLLECTION AND METHODS

The Northfield Township Schools have worked over the past two years to research best practices

in four areas of our language arts/English programs: literature/reading, writing, vocabulary, and

speaking/listening. These four areas of the discipline are all measured on a variety of

standardized tests and appear on the Illinois state standards. The survey questions that teachers

were asked were based on Best Practice research and will help to guide our Township

articulation and professional development over the next few years. The survey took

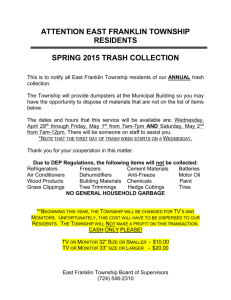

approximately 30 minutes and a total of 96 teachers took the survey. The graphic below

represents the Township schools participation:

Northfield Township Language Arts Professional Development Survey

Please identify the school where you teach:

Answer Options

Attea

Field

Maple

Northbrook Jr. High

North Shore

Academy

Springman Jr. High

Wood Oaks

Glenbrook North

Glenbrook South

Other (please specify)

Response Percent

Response Count

6.3%

3.2%

4.2%

5.3%

6

3

4

5

0.0%

0

6.3%

13.7%

29.5%

31.6%

6

13

28

30

3

14

During the course of the study, each school recorded their current state of the content and skills

in each of the following sub groups: Research, Readings (Novels, Short Stories, Poems),

Teaching Writing, Writing Products, Support Systems, and Technology. Each school’s

representative recorded, to the best of his or her ability, the practices and materials used in the

language arts/English program.

FINDINGS

The following data reports on some of the highlights from the survey taken by the Township

teachers. 77% of teachers use the Illinois State Standards to influence their assessments, and

43% used the College Readiness Standards to influence their assessments.

In the category of Writing, the survey results showed that 100% of the teachers use

rubrics for evaluating student work. 90% of teachers reported they work in teams to share

assessment data/information, and 90% also said they adapt instruction based on

assessment information.

In the area of Literature, the survey showed that 95% of the teachers required students to

annotate fictional texts, and 86% required students to annotate non-fictional texts. In the

area of technology and reading, 31% assigned electronic texts as part of their course

readings. 89% of teachers said that they adapt instruction on the basis of assessment.

In the area of Vocabulary, the survey results showed that 75% of teachers pre-teach

vocabulary before a reading selection, while 94% teach vocabulary in context. 74% of

teachers design instruction that gives students opportunities to use newly learned

vocabulary, and 80% of teachers adapt instruction on the basis of student assessment.

In the area of Speaking and Listening, 90% of teachers cited they have students deliver

formal individual presentations, and 94% make informal individual presentations a part

of their instruction. 92% of teachers make time for formal and informal group

presentations, while 87% have students debate issues in their classroom. Also noteworthy

was that 70% of teachers use technology to support presentations, and 67% have students

evaluate other speakers. 87% employ active listening skills in practice settings.

SECTION THREE: SKILLS CONTINUA

Skills continua and content maps are recorded and posted on the Township Wiki as they have

been developed at articulation meetings and at home schools. This represents the most up-todate information from each of the Township schools.

http://northfieldtownshipschools.pbworks.com/

SECTION FOUR: ALIGNMENT TO STATE STANDARDS

During the entire process of the English/Language Township work, the Illinois state standards

were used to align objectives, create categories, guide research, and create survey questions. The

updated Illinois state standards are linked to the Township Wiki.

http://northfieldtownshipschools.pbworks.com/

15

SECTION FIVE: IMPLICATIONS FOR INSTRUCTION AND PROFESSIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

The research and survey results indicate that practice in the Township is strong and professional

development needs to focus on continued revision and refinement of design and practice. In 2007

and 2009, the Fall Township Articulation Meetings focused on establishing what the present

practices in curriculum and instruction are in the instruction of literature/reading,

writing/research, and speaking and listening. Based on the findings, the Northfield Township

Language Arts/English Articulation Committee makes the following recommendations:

Northfield Township middle and high school teachers should improve and continue to:

o view reading, writing, speaking and listening as reciprocal processes and provide

practice in all domains

o help students develop voice through oral conversation of various forms

o view writing as a thinking tool rather than a product with absolute answers

teach writing as a recursive process

include free-writing opportunities to promote student thinking

allow for brainstorming, outlining, drafting, note-taking, and getting

feedback during writing

build in time for students to write, interact with others about their writing,

and reread and revise their work

help students develop a sense of voice in their writing through

social interaction and rehearsal of the writing process

use mini-lessons, small groups, and individual conferences to promote

writing

teach the conventions and grammar of standard English and may

strengthen these conventions by using the context of student writing

o create opportunities for students to write for various purposes

provide opportunities for students to write about real-life experiences

provide models of good writing across a variety of genres

o create opportunities for students to explore, collaborate, and create new products

o be aware of factors that impact student learning such as gender, culture,

community, individual interests, as well as psychological, developmental and

circumstantial needs of students

o recognize that technology is a commonplace tool used by students in their daily

lives. Therefore, in instruction teachers should:

use technology to support the teaching of both reading and writing

regard all forms of technology as instruments for learning

use language-based, non-verbal, or artistic devices in the writing

classroom

allow for the use of all forms of visual, artistic, or performance-based

media and technology in the English classroom.

o view the teaching of literature through the lens of the reading instruction process

using the stages of reading - pre, during, and post – as a guide for instruction

16

o use the explicit instruction of reading strategies to develop students’

metacognitive skills

predicting / inferring

questioning

connecting

determining importance

synthesizing

visualizing/sensory imagery

o use a variety of genre and subject matter that reflect the “mirrors and windows”

perspective of choosing literature

ensure that there is a balance of independent and whole-class reading

ensure that there is a balance of pleasure vs. assigned reading

o model reading strategies including

developing one’s own reading process

marking up/annotating text for multiple purposes including noticing text

structure

o incorporate speaking and listening activities throughout the curriculum

o incorporate vocabulary instruction throughout the curriculum

o make use of assessment in multiple ways including

using both formal and informal assessments

using both conventional and unconventional methods of assessment

using a wide variety of assessment tools across a variety of products

considering portfolios as a means to monitor student growth

giving careful thought to the construction of rubrics for the assessment of

writing

The list above reflects the multiple demands of the language arts/English curriculum and

instruction. Through the committee research and Township survey, the decision was made to

focus the morning of this past fall’s articulation on reading and the afternoon on continued

middle school-high school teacher articulation. Carol Jago, president of the National Council of

Teachers of English, presented the argument that we need to carefully evaluate the amount and

difficulty of the reading we have students do. She advocated for teachers to ensure that students

read often fiction and non-fiction literature that appropriately challenges them in many ways.

Teachers left the morning session with a renewed energy to evaluate the literature they teach

based on Dr. Jago’s perspective.

SECTION SIX: LIMITATIONS OF STUDY AND REPORT

Although we feel that the Township Curriculum Study for English has been extremely

successful, we recognize that the research has some limitations. The committee members were

diligent in their work. However, the communication group’s research was incomplete, and due

to limited time, two of the committee chairs had to take over the research topic on short notice.

Another limitation was the timing of sending the survey to the Township districts. The survey

was sent to the 6th through 12th grade Township teachers towards the end of the school year.

Although some Township districts had 100% participation in the survey, others had less than

50% participation. An additional limitation involving the survey is that different people may

17

have interpreted the same question quite differently. This became evident when analyzing some

of the respondents’ comments. On the day of articulation, it was the committee’s hope that we

would have full and equal representation as we began to map skills and content across grade

levels. This was not the case. For example, we sometimes had an eighth grade reading teacher

attempting to represent writing practices for his or her entire school or district. In addition,

several of the Township Curriculum directors changed during the time of the study due to

retirement and administrative moves. With these changes, adjustments and modifications to the

study were necessary.

We have valued the process involved in answering the essential questions, the opportunity to

collaborate with the Township English teachers, and the learning that has occurred. We look

forward to future discussions, additional Township wide professional learning opportunities, and

continued articulations between the sender schools and the high schools.

SECTION SEVEN: CONCLUSION

Over the past three years, the middle school and high school teachers have begun to identify the

content and skills that are taught at the different levels. This is the first step in establishing

standards and goals for grade levels that will more readily ensure a smooth transition from

middle school to high school. The recursive and divergent nature of our discipline continues to

challenge some of this work, but the research done by the committee provides guideposts for our

areas of professional development.

Two additional elements now add to the complexity of our continued work and articulation. The

Response to Intervention (RtI) law now touches the high school and will certainly influence the

nature and perimeter of our discussions. Also, our committee used 21st Century Learning Skills

in many of our discussions, but struggled to always find a way to authentically integrate into our

work. On-going study by the Township English teachers in this realm should continue. We have

the expertise and resources in all of the districts to make that happen.

The four facilitators of the Township report will continue to meet to plan the annual articulations

and keep the Township focused and moving forward. This past fall, the articulation meeting

focused on reading instruction and the reporting of curriculum and instruction in key areas of

writing, literature and support services. The structure of having a morning keynote for grades 6 –

12 teachers followed by work in small groups in the morning and then grades 8 and 9 teachers

working together in the afternoon kept everyone energized and engaged. That structure should

continue.

18

SECTION EIGHT: FUTURE INITIATIVES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The need for annual articulation meetings is clear. The predominant request from middle school

and high school teachers alike on the October 2009 articulation meeting’s evaluations was for the

middle school and high school teachers to keep meeting and talking to each other. Continued

conversation should be the aim of any curriculum work since curriculum is dynamic, evolving to

meet the common needs of all students in each district in the Township. Ongoing articulation

among the Township districts bodes well for future professional development and for improved

transition from middle school to high school.

The survey identified inconsistencies in the application of writing standards across the Township

districts. Teachers use various writing standards to guide their instruction and assessment. For

example, fewer than 50% of teachers refer to Illinois State Standards most or all of the time;

fewer than 25% refer to the College Readiness Standards and only 25% refer to the National

Council of Teachers of English/International Reading Association standards most or all of the

time. In addition, the National Common Core standards will be published in March 2010. Since

the State of Illinois is a finalist for the Race to the Top federal funds, the state adoption of the

National Common Core standards is imminent. These findings indicate the direction of our

future professional development. First, Township teachers must identify the consistencies among

the standards that are used and the gaps that need to be bridged. Once the standard language is

identified, understood, and agreed upon by the teachers, a common set of scaffolded writing

standards can be created and integrated into our practice. Instruction and assessment can then be

better delivered across the Township. Because of the recursive nature of writing development, a

set of student writing exemplars from grades six through ten should be compiled. These samples

would demonstrate the expected level of development at each grade.

The goals of the proposed articulation cannot be accomplished in one day. The fall articulation

should be viewed as a day in which a strong foundation is established. The committee

recommends that all of the middle school districts participate in at least one additional day of

professional development and articulation. The goal of this additional work would be to bring

consistency in the application of the common Township standards at the middle schools.

Similarly, the two high schools should participate in a second professional development

articulation to bring consistency between the two schools. At least one articulation meeting per

year with middle school and high school teachers should be continued in ensuing years to

strengthen the use of common standards. This process would strengthen the transition from

middle to high school. An additional recommendation is to provide a representative from the

respective high school(s) for language arts curriculum initiatives at the middle school level.

For the October 2010 articulation day, the committee would like to bring in a dynamic speaker

who could address the Common Core Standards and the commonalities with the other standards

mentioned above. This person would help on that day to guide the Township teachers in

developing the foundation of our Township writing initiative. If this is a local person, their

continued guidance would be important. A spring meeting and summer workshop that includes

all of the committee members are needed to plan and realize the articulation.

19

In October 2009, the Township articulation meeting had a focus on reading in the twenty-first

century. The success of that day is reflected in the documentation of the teachers’ work posted

on the wiki and in the professional, complex discussion that happened on that day. The

excitement and energy produced last October endures in professional discussions among

colleagues to this day. The proposed plan outlined above builds on the groundwork of curricular

exploration and collegiality that was established.

20

Works Cited

Adler, Mortimer. “How to Be a Demanding Reader.” How To Read a Book.

Adler, Mortimer, and Charles Van Doren. New York: MJF Books, 1940.

45-56.

Allen, Janet. Words, Words, Words. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse Publishers, 1999.

Atwell, Nancie. In the Middle: Writing, Reading, and Learning with

Adolescents. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1987.

Banks, James A. "Teaching Literacy for Social Justice and Global

Leadership." Language Arts 81.1, 2003: 18-19.

Blachowicz, Camille L., and Peter Fisher. Teaching Vocabulary in All

Classrooms. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001.

Bloom. Benjamin. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Bloom, et al. 1974.

Bomer, Randy. "Writing to Think Critically: The Seeds of Social Action."

Voices from the Middle 64: 2-8, 1999.

Bromley, Karen. "Nine Things every teacher should know about words and

vocabulary instruction." Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 50 (2007).

Chapman, Anne. Making Sense: Teaching Critical Reading Across the

Curriculum. College Entrance Examination Board, 1993. 50.

Cobb, Charlene. Effective reading instruction begins with purposeful assessments. Reading

Teacher. 57 (4) 386-388, 2003.

Collier, Lorna. “The Shift to 21st-Century Literacies.” The Council Chronicles.

November, 2007.

Davis, Chris and Jennifer Davis. “Using Technology to Create a Sense of

Community.” English Journal. Vol. 94, No. 6. July, 2005.

21

Fletcher, Ralph. Boy Writers: Reclaiming Their Voices. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse

Publishers, 2006. Notes from Ralph Fletcher presentation, November,

2007.

Fletcher, Ralph. Live Writing: Breathing Life into Your Words. New York:

Avon Books, Inc., 1999.

Joshi, R. M. "Vocabulary: A Critical Component of Comprehension." Reading

& Writing Quarterly, 2005, 21:209.

Kamil, Michael L. "Adolescents and Literacy: Reading for the 21st Century."

Alliance for Excellent Education. November, 2003.

Kinsella, Kate, Colleen Stump, and Kevin Feldman. "Strategies for

Vocabulary Development." Pearson eTeach. 2002. Pearson Prentice

Hall. 1 Oct. 2008 phschool.com.

Kruideneier, John. Research-based Principles for Adult Basic Education. The Partnership for

Reading. RMC Research Corporation: Portsmouth, New Hampshire, October, 2002.

Learning for the 21st Century: "A Report and Mile Guide for 21st

Century Skills." Partnership for 21st Century Skills. 2002.

Luke, Allan. "Literacy Education for a New Ethics of Global Community."

Language Arts 81.1 (2003): 20- 22.

Mancina, Hannah. "Empowering Students Through a Social Action Writing

Project" English Journal 94.6 (2005): 31-35.

Maynard, John. “Model Questions and Key Words to Use in Developing

Questions.” Unpublished handout. Pomona, CA.

Murray, Donald. "Teaching Writing Your Way". Adolescent Literacy: Turning

Promise into Practice. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2007, 179-187.

22

Murray, Donald. Write to Learn. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston,

1987.

National Council of Teachers of English. Resolution on Including Speaking and

Listening in National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

Assessments. Urbana, IL. , 2008.

National Council of Teachers of English. 21st-Century Literacies. A Policy

Research Brief. Urbana, IL., 2007.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. "What Works In

Comprehension Instruction." AdLit.org. 25 June, 2008

<www.adlit.org/article/105>.

National Institute for Literacy. "What Content-Area Teachers Should Know

About Adolescent Literacy." (2007).

National Reading Panel. Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching People to Read.

Washington. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000.

Pink, Daniel H. A Whole New Mind. New York: Penguin, 2005.

"Questions about Vocabulary Instruction." AdLit.org. 25 June 2008

<http://www.adlit.org/article/3471>.

Rasinski, Timothy, Padak Nancy, Newton Rick, and Newton Evangeline.

Building Vocabulary from Word Roots. Huntington Beach, CA: Beach

City P, 2007. 12-12.

Ray, Katie Wood. The Writing Workshop: Working Through the Hard Parts.

Urbana: NCTE, 2001.

Rief, Linda. "Writing: Commonsense Matters." Adolescent Literacy: Turning

Promise into Practice. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2007, 189-208.

23

Romano, Tom. "Teaching Writing from the Inside". Adolescent Literacy:

Turning Promise into Practice. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2007, 167178.

Smagorinsky, Peter. Teaching English by Design: How to Create and Carry

Out Instructional Units. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2008.

Texas Education Agency. "The Components of Effective Vocabulary

Instruction." AdLit.org. 25 June, 2008 <http://www.adlit.org/article/1969>.

Tompkins, Gail E., Cathy L. Blanchfield, and Patricia A. Tabloski. Teaching

Vocabulary : 50 Creative Strategies, Grades K-12. Upper Saddle River:

Prentice Hall, 2003.

Weinstein, Larry. Writing at the Threshold. Urbana: National Council of

Teachers of English, 2001.

Wolf, Dennie Palmer. Reading Reconsidered: Literature and Literacy in High

School. The College Board, 1988.

Writing Study Group of the NCTE Executive Committee. “Beliefs About the

Teaching of Writing.” National Council of Teachers of English, 2008.

<http://www.ncte.org/about/over/positions/category/write.

Yopp, Ruth Helen, and Hallie Kay Yopp. "Ten Important Words Plus: A

Strategy for Building Word Knowledge." The Reading Teacher, 2007, 61: 157-60.

24