ConscriptionHandout

advertisement

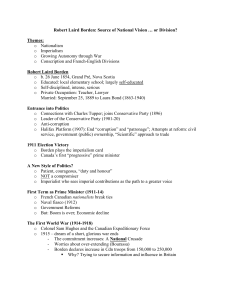

Conscription Crisis World War I broke out in 1914. As a Dominion of Great Britain, Canada was automatically at war. By 1916, the French and British armies had suffered heavy casualties, and the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was desperate for reinforcements. Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden was an ardent imperialist (i.e., supporter of Britain), and he was determined to maintain Canada's WW1 participation to prove Canada was equal to Great Britain and not a mere colony. Volunteers for Canada’s army were becoming harder to find, and Borden was convinced that forced conscription (i.e., a draft) was needed to make up for losses. Borden tried to pass the Military Service Act to establish conscription, but many Canadians such as farmers, union heads, pacifists and French-Canadian opposed the idea. Border sought the support of women to establish conscription. At this time, women could NOT vote in federal elections. Women’s groups promised to support Borden and conscription IF Borden gave the vote to female relatives of soldiers (i.e., mothers and wives of soldiers). Borden pushed through the Military Voters Act and the Wartime Elections Act. The former action gave Canadian soldiers fighting in France the right to vote, while the latter gave the vote to female relatives of Canadian soldiers. The latter action was the first step towards all Canadian women securing the right to vote in Canadian elections. Borden called an election on the conscription issue. For many Canadian women, this would be the first opportunity to vote in a federal election. The protests against conscription were violent. In Quebec, a riot resulted in four deaths. On 29 August 1917, the Military Service Act became law, and 99,561 men were conscripted as reinforcements. In the end, conscription came too late, and only 24,100 conscripted soldiers actually fought. In the end, Canada was deeply divided. Borden lost support in Quebec and the West, and he was later defeated in a federal election. Conscription Crisis In 1917, Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden decided to introduce conscription to ensure Canada’s army had enough men to keep fighting. Borden used the following information to make his decision. Graph the data and explain how it helped with Borden’s decision. (i.e., What does the graph tell you?) Table 1: Canadian WWI Volunteers and Number of Canadian Casualties (Deaths and Wounded) in 1917. Month January February March April May June July August September October November December Number of Volunteers 9,250 6,700 5,600 5,500 5,400 4,300 3,800 3,100 3,000 3,000 4,000 3,900 Number of Casualties 4,400 3,250 6,200 13,500 13,500 8,000 10,000 24,000 30,000 9,500 18,500 12,500 Canada and the 1917 Conscription Crisis In 1916, Prime Minister Robert Borden toured the battlefields of France. Borden saw the horror of war firsthand, and he realized that additional Canadian troops were badly needed. At the same time, the number of men volunteering for military service in Canada was dropping. Borden decided there was a need to conscript men into serve with the Armed Forces. Conscription divided Canadians. Pacifists, farm groups, labour organization and many French Canadians were opposed. Leader of the Opposition Sir Wilfrid Laurier noted, “The law of the land…declares that no man in Canada shall be subjected to compulsory military service except to repel invasions or for the defence of Canada.” To gain support for conscription, Borden passed the Wartime Elections Act. The law allowed the female relatives of soldiers to vote in federal elections. The pre-election rigging turned out to be critical. Many people voted for conscription because they had family members overseas and wanted them to come back alive (i.e., they thought the more soldiers at war, the better the chances). In January 1917, the Military Services Act passed into law. The Act required males between the ages of 18 and 45 to enlist for military service. The civilian vote across Canada was split nearly 50/50 along linguistic lines. Most proconscription votes were from English-speaking Canadians, while many anti-conscription votes were from Quebec. The outcome affected French-English relations. French Canadians felt cheated by conscription because they did not want to get involved in the "European War". English Canada portrayed French-Canadians as traitors. It is important to note that the conscription question split Canada along urban-rural lines. Urban Canada was pro-conscription; whereas, farmers voted against conscription. In other words, the Conscription Crisis may not be entirely a French-English struggle. Rather, conscription divided Canada along different lines, and other issues (e.g., poor recruiting methods in Quebec) only added to the crisis. Questions 1. What does “conscription” mean? 2. Define “pacifist.” 3. What crisis in military recruitment led to the call for conscription? Why did it take three years of fighting for the crisis to develop? 4. Why might farmers be opposed to conscription? 5. How are the Conscription Crisis and Women’s Right to Vote linked?