in bad company

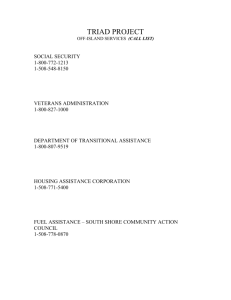

advertisement