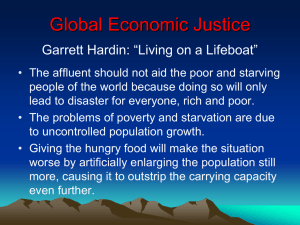

Lifeboat ethics case2

advertisement