Skill: National Bureau for Students with Disabilities

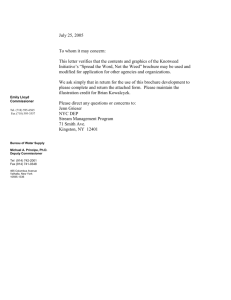

advertisement