3 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship

advertisement

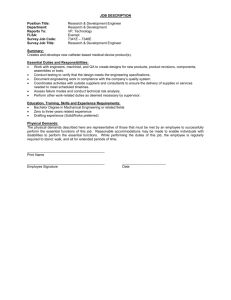

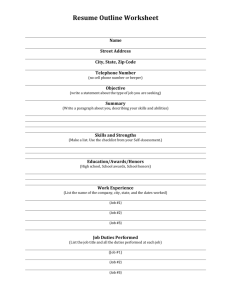

Working draft Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship: why should a liberal behave ecologically in his private sphere? Association for Legal & Social Philosophy Conference 2007 19th - 21st April 2007, Keele University UK Stijn Neuteleers Centre for Ethics, Political and Social Philosophy Katholieke Universiteit Leuven – Belgium stijn.neuteleers@econ.kuleuven.be http://www.econ.kuleuven.be/stijn.neuteleers/public ‘Can we survive in freedom? This may well be the most significant question before us, and I am not at all sure about the answer. For those who share my belief that freedom matters above all – even above survival – the alternative is literally vital’ Ralf Dahrendorf (1994: 18) Introduction The question I would like to examine in this paper is the following: is it possible to conceive environmental duties in the private domain within the framework of political liberalism? This is a question on the interface between green political theory and political liberalism and I believe that such an interaction can be especially fruitful. The question I will deal with can provide interesting insights for both domains, namely: can we think of private duties within liberal theory and can we think of environmental duties which take freedom into consideration? I hope the answers on these questions will not only be relevant on a theoretical level, but also on a more practical level, in the sense that the insights provided here can be interesting for people struggling with the question how to be a good environmental citizen. For the answer on my research question I will elaborate Derek Bell’s account of liberal environmental citizenship (Bell 2005). After discussing the contemporary debate on citizenship (part 1), I will outline the different sources, rights and duties of Bell’s account of liberal environmental citizenship (part 2). Bell suggests two ways of conceiving private duties within a liberal framework and, in this paper, I will further develop these two ways (part 3). However, it is not as easy to determine the content of ‘private’ as might appear at first glance. Moreover, the distinction between public and private is different for each of the two kinds of Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship private duties. First, one has the negative duty to comply with existing laws, but there are cases in which the law is non-enforceable because of (local) privacy (private sphere). In this case, under specific conditions, one might have a negative ‘private’ duty (part 3.1). Second, one has the positive duty to promote just institutions, but there are be cases where this promoting is not the main intention of one’s action (private action). Nevertheless, under specific conditions, one might have a positive ‘private’ duty (part 3.2). These two ways of conceiving private duties will be made concretely by presenting several examples regarding the question: ‘should I, as a liberal, behave ecologically in my private sphere?’ (part 4). Under the title ‘discussion’ I will mention some problems of the presented account, especially the potential shortcomings of a liberal approach (part 5). I start with the debate on citizenship. 1 The citizenship debate and the ecological challenge In the 1970s and 1980s the keywords of the debate in Anglo-American political philosophy were respectively justice (rights) and community (membership). By 1990, citizenship became one of the central concepts – the ‘buzzword’ amongst thinkers on all points of the political spectrum (Kymlicka 2002: 284-7). By then, the classical liberal conception of citizenship has proven to be inadequate. Many classical liberals believed that a liberal democracy could function effectively by creating sufficient checks and balances; virtuous citizens were not necessary for a successful functioning of such a democracy. However, it has become clear that procedural-institutional mechanisms to balance self-interest are not enough and some level of civic virtue and public spiritedness is required. The health and stability of a modern democracy depends, not only on the justice of its institutions, but also on the qualities and attitudes of its citizens. Because of this, there was a need for a more ‘active’ interpretation of citizenship: to supplement the traditional ‘passive’ citizenship-as-rights with an active exercise of citizenship responsibilities and virtues. Theories of citizenship are now widely seen as a necessary supplement to theories of institutional justice. In sum, ‘theories of citizenship identify the virtues and practices needed to promote and maintain the sorts of institutions and policies defended within theories of justice’ (Kymlicka 2002: 287; my italics). I think there are two main, frequently cited, ecological challenges to citizenship and these challenges are mainly situated on the ‘where’ (where citizen actions can be found) and ‘what’ (content of rights and obligations) dimension (Saward 2006). First, environmental impact of our behaviour is not limited to the national state and therefore the state is challenged as being the exclusive framework for citizenship (internationalisation challenge). Secondly, environmental impact is not limited to our actions in the public sphere and therefore the public domain is challenged as the exclusive domain of citizen actions (public/private challenge) (see Dobson 2006; Dobson & Bell 2006; van Steenbergen 1994). However, these two dimensions are not exclusively challenged by ecologism, more specifically, the state as framework is challenged by cosmopolitanism and the private/public distinction is challenged by feminist thought (Dobson 2006). Nevertheless, these challenges are not the same as the ecological ones: i) cosmopolitanism is concerned about entitlements in general, whereas 2 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship ecologism is mostly focused on causal relations ii) whereas both feminism and ecologism contest the private/public distinction, their main subject is different, namely, respectively, intimate relationships and consumption behaviour. In this paper, I will focus on the private/public challenge and only deal with the internationalisation challenge indirectly. As mentioned above, citizenship theories identify the virtues and practices needed to promote and maintain the institutions defended within theories of justice. The current debate mostly concentrates on those virtues which are distinctive to modern pluralistic liberal democracies, such as willingness to question political authority and to engage in public discourse. According to Kymlicka, it is not necessary that every citizen display all of these virtues in a high degree. Liberal justice requires a critical threshold: there must be a sufficient number of citizens who posses these virtues in a sufficient degree. Nevertheless, there is a growing fear that we are dangerously close to falling below such a threshold. How can this be overcome? This question is mainly tackled by ‘civic republicanism’ and within civic republicanism there are two camps answering this question. First, there is the Aristotelian interpretation: political participation is not seen as a burdensome obligation, but rather as intrinsically rewarding. Secondly, there is the liberal interpretation: liberals accept that for many people duties may be felt as a burden. However, they emphasize that there are strong instrumental reasons why citizens should accept this burden, namely in order to maintain the functioning of democratic institutions and to preserve basic liberties. Liberals look upon the Aristotelian interpretation as ‘perfectionist’, namely as unfairly privileging one particular conception of the good over others. ‘Aristotelian republicans assume that people have turned away from political participations because they find politics unfulfilling. Our attachment to private life, I believe, is the result, not (or not only) of the impoverishment of public life, but of the enrichment of private life’ (Kymlicka 2002: 297). In this paper I would like to work with a liberal and thus instrumental account of citizenship duties. Why could it be interesting to develop a liberal account of environmental citizenship? A lot of authors are suggesting that liberal duties are insufficient from an environmental point of view and therefore a liberal approach is to be rejected. However, I think a liberal account of environmental citizenship might be especially useful for two reasons. First, on an individual level, the notion of environmental citizenship is relevant for the question ‘what should I do in my life for the environment?’ and, consequently, what can be expected others do for the environment. A lot of environmental activists are prepared to make great sacrifices because they assume these sacrifices are necessary, and, consequently, they think everybody should do. Since liberalism attach much value to personal freedom, it is interesting to investigate this question from a liberal perspective. Secondly, a liberal account of environmental citizenship can inform us about the compatibility of liberalism and ecologism: are the duties of a liberal environmental citizenship sufficient from an ecological point of view? I put this question aside here, but I will return to this at the end of this paper. 3 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship 2 2.1 Liberal environmental citizenship: Derek Bell Legitimate sources of liberal citizenship rights and duties Here, I will consider Bell’s approach of liberal environmental citizenship (Bell 2005; see also Bell 2003; 2004). My aim in this paper is not to criticize Bell’s account, but rather to develop his account more in detail, especially in relation to duties in the private sphere. The first step, before outlining rights and duties of liberal environmental citizenship, is to examine the legitimate sources of citizenship rights and duties. Bell states that within contemporary liberalism the physical environment is primarily conceptualised as property. The environment is included in civil and political rights by means of property ownership rights. Contemporary liberals also recognise the importance of basic needs, but the fulfilment of these needs is not seen as related to the environment. The way the environment is currently conceived within the theories of contemporary political liberals (such as John Rawls, Brian Barry and Charles Beitz) is, according to Bell, inconsistent with key elements of these theories. According to Bell, there are two legitimate sources for environmental protection within liberalism, namely the right to have our basic needs met and the ‘fact of reasonable pluralism’. First, the importance of the fulfilment of basic needs is recognized by contemporary liberalism. Nonetheless, since the state must do far more than provide for basic needs, the bodily survival is taken for granted and has become less central. However, because of environmental problems the self-evident fulfilment of basic needs can no longer be taken for granted; even the most elementary goods, such as clean air and water, are no longer a matter of course. Bell states that liberalism ignores the fact the basic needs only can be met through the exploitation of the physical environment. If liberals are concerned about the fulfilment of basic needs of current generations and if they are concerned about the maintenance of liberal societies in the future (basic needs of future generations), than they have to adopt a principle of environmental sustainability, which is grounded in a conception of the environment as ‘provider of basic needs’. Moreover, insofar as meeting basic needs is a priority for liberals, it is this conception of the environment as ‘provider of basic needs’ that must take priority. Contemporary liberalism must at least conceive the environment also as ‘provider of basic needs’ and this conception has priority insofar the meeting of these basic needs is a priority for liberals1 (Bell 2004: 6-7; 2005: 182-3)2. Second, the second feature of political liberalism we need to consider is what Rawls’s ‘fact of reasonable pluralism’. A modern democratic society is characterized by a pluralism of For instance, John Rawls states that ‘basic rights and liberties may easily be preceded by a lexically prior principle requiring that citizens’ basic needs be met, at least insofar as their being met is necessary for citizens to understand and to be able fruitfully to exercise those rights and liberties’ (Rawls 1993: 7; my italics). 2 The restriction of ecological justice to the fulfilment of basic needs, leaves some questions open, such as: i) is there room for more far-reaching conceptions of (ecological) justice; ii) should sustainability (and its intergenerational aspect) be restricted to the fulfilment of human basic needs (as in the Brundtland definition); ii) does the stress on basic needs imply a cosmopolitan account; the latter is acknowledged by Bell in a footnote (Bell 2005: 193n.7). 1 4 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship incompatible yet reasonable comprehensive doctrines. This is a permanent feature of the public culture of democracy and it is the inevitable outcome of the exercise of human reason within the framework of free institutions. A political conception of justice is presented in its justification as being without any reference to any reasonable comprehensive doctrine (Rawls 1993: xvi, 12). Therefore political liberalism is not committed to and must abstain from any substantive conception of the environment, as being part of a comprehensive doctrine of the good. The prevalent liberal conception of the environment as property3 is just one of many reasonable conceptions of the environment. Because liberals cannot ground arguments about political justice in comprehensive doctrines, they can no longer conceive the environment exclusively as property. But if the fact of reasonable pluralism rules out the conception of the environment as property, does the same not hold for the conception of the environment as ‘provider of basic needs’? Bell states that the latter is consistent with reasonable pluralism since no reasonable comprehensive doctrine could deny either the factual or normative elements of that conception: i) any doctrine will recognize the fact that human survival depends on the physical environment (water, air, food, etc.); ii) any doctrine will recognize survival as a good, since it is a precondition for pursuing other goods. However, if liberalism is to be neutral on controversial metaphysical and moral issues, is there any other conception of the environment liberalism can endorse? According to Bell, the fact of reasonable pluralism suggest that there is one possible conception, namely the environment as ‘a subject about which there is reasonable disagreement’. This conception implies a certain mode of environmental decision-making, namely a democratic one. Citizens must have the opportunity to persuade others of their conception of the environment. So, whereas the conception of the environment as ‘provider of basic needs’ is tied to substantial principles of justice, the conception of the environment as a subject about which is diagreement is tied to procedural principles. Beyond what is required for the fulfilment of basic needs, political debates about the environment are debates between comprehensive doctrines and state policies will reflect the conceptions that win in the democratic procedures4. There is only one moment citizens cannot appeal to their comprehensive doctrines, that is in the prior debate about how environmental decisions should be made (the justice debate) (Bell 2005: 184-6). To sum up, according to Bell, the problem with contemporary liberalism is not that the list of rights is not extensive enough, but rather that is has an untenable conception of the environment: ‘this conception of the environment as property not only ignores the role of the 3 I think that the implicit and problematic conception of contemporary liberalism is another than the ‘environment as property’. It seems difficult to think about environmental protection without any form of property (the non-existence of property rights can be one of the causes of ‘the tragedy of the commons’ and the assignment of property rights can be one of the options to protect the commons). Perhaps a better suggestion would be that contemporary liberalism conceives the environment as ‘provider of commodities’, such as wood, food, minerals and water. It is probably this conception which conflicts with the satisfying of basic needs (cf. the debate between multinational corporations (MNCs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) which respectively see water as a commodity or as a basic right). However, I don’t think this undermines Bell’s contention that contemporary interpretations of political liberalism prioritise one particular conception of the environmental. 4 This statement may seem controversial, but I think the counter-arguments are convincingly addressed by Bell (2002). 5 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship environment in satisfying our (liberal) rights to have our basic needs met (environment as provider of basic needs) but also is inconsistent with the liberal commitment to the fact of reasonable pluralism (environment as subject about which there is reasonable disagreement)’ (Bell 2005: 186). 2.2 Liberal environmental citizenship rights Until now we have considered two legitimate sources of a liberal environmental policy. From these two sources liberal environmental citizenship rights can be derived (Bell 2004: 9-11; 2005: 186-8). Substantive (versus procedural) environmental rights can be derived from the first source, namely the idea that the environment is crucial for the fulfilment of basic needs. This corresponds with most liberal approaches, which focus on rights to particular environmental goods, such as clean air and water. The dissension about the detailed specification of the substantive environmental rights cannot be ‘rationally’ resolved, but must be resolved by means of democratic decision-making procedures. If citizens in a liberal democracy have a substantive right, they should also have a corresponding procedural right, namely the right to defend the substantive right. This procedural right can take two forms. First, there is the right to defend and claim an already existing legal right. Second, if such a right does not exist already, one has the right to campaign for it. From the second source of liberal environmental policy, namely the conception of the environment as a subject about which there is disagreement, two types of rights can be derived. First, citizens should have procedural rights to participate in the process of policymaking about the environment. Liberal citizens have the right to promote their own conception of the ‘good environment’ through the democratic process. However, this promoting is limited by the substantive right to have the basic needs satisfied; beyond this requirement, one can adhere to one’s own conception of the ‘good environment’ in the democratic debate. Note that, the liberal environmental citizen might prefer tarmac to ‘green’ spaces; as long as this preference does not violate the substantive right about basic needs, the liberal environmental citizen needs not to be ‘green’. Second, Bell states that there is also another type of rights derived from the conception of the environment as subject of disagreement, namely ‘personal rights’: ‘In those “spaces” where the state does not prescribe action, individual citizens have the right and the freedom to choose to take the environmental effects of their actions into account’ (Bell 2005: 187). I would like to make one comments on these ‘personal rights’, namely about the argument for it. The function of these rights is not to maintain reasonable pluralism, but to indemnify freedom of choice as a precondition for realizing the good live. Freedom is a precondition because, on the one hand, we want to live our lives from the inside, in accordance to our beliefs about value; it is difficult to imagine that someone leads a better life if he of she goes against his or her deepest ethical convictions, instead of living in accordance with these 6 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship convictions. On the other hand, one should be free to revise one’s projects if one comes to believe that these are not worthwhile (Kymlicka 2002: 222). 2.3 Liberal environmental citizenship duties Liberal citizens have both negative and positive duties, namely, respectively, the duty to obey and to promote just institutions. I follow Bell’s discussion (2005: 188-9) and start with the negative duties: the duty to comply with just institutions and apply to them. In our case the just institutions are environmental laws. When is an environmental law a just law? There are two legitimate sources. First, the law is made to guarantee substantive environmental rights (‘environment as provider of basic needs’) and came into being through a democratic decision-making process. Second, the law relates to our ideals of the good environment (environment as subject about which there is reasonable disagreement) and has been made by voters in a (deliberative) democracy. In addition to negative duties, liberals also have positive duties, namely ‘to further just arrangements not yet established, at least when that can be done without too much cost to ourselves’ (Rawls 1999(1971): 99). This is a necessary element of citizenship theories, since, as we have seen, theories of citizenship identify what is needed to promote and maintain the sorts of institutions defended within theories of justice (see above). However, the potential scale of such a positive duty is enormous, especially since a lot of environmentalist theories take a cosmopolitan stance. ‘Liberal environmental citizens in any contemporary democratic society could devote every minute of their lives to promoting global environmental justice and still leave plenty for others to do. In other words, the duty to promote just arrangements could be utterly all consuming leaving no space for decent liberal environmental citizens to do other things or have “more rounded” lives’ (Bell 2005: 189). Therefore, in a world where there are serious injustices, a ‘cost proviso’ is needed: we should only further just institutions when this can be done without too much cost to ourselves. However, several problems are attached to the idea of a ‘cost proviso’: there is the obvious problem of defining its limits and it opens the possibility that some rights are unsecured while no one fails to do their duties (Bell 2004: 13). This conception of liberal environmental citizenship duties does not encompass the duty to protect ‘green spaces’. Of course, citizens are allowed to campaign for this if it fits in with their conception of the good environment; nevertheless, this is not required to fulfil their duties of liberal environmental citizenship. In order to understand the meaning of these liberal citizenship duties, it is useful to compare them with the duties of another approach of environmental citizenship, namely the ecological citizenship notion of Andrew Dobson. The starting point of Dobson (2003; 2006) is ‘ecological non-territoriality’: environmental problems do not respect national boundaries. Therefore, ecological citizenship requires a new conception of political space. The relationship that is relevant for environmental problems is the practical, material and causal relationship; this relationship produces the relevant political space. These relationships of harm are both potentially international and intergenerational. According to Dobson, the relevant political space is best expressed by the notion of ‘ecological footprint’: this is a 7 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship measure of consumption of natural resources, which is expressed in surface area (hectares). Dobson connects this notion of political space with the normative contention that everyone should have disposal of an equal share of ecological space. Since the total ecological space is limited, one harms someone else if one uses more than one’s fair share of ecological space. This implies the following citizen duty: one should take care that one’s footprint is not bigger than the fair and sustainable footprint. ‘The nature of the obligation is to reduce the occupation of ecological space, where appropriate, and the source of this obligation lies in remedying the potential and actual injustice of appropriating an unjust share of such space’ (Dobson 2006: 230). Regarding citizenship duties, there are at least three important, interconnected differences (Bell 2003) between Dobson’s account of ecological citizenship and Bell’s account of liberal environmental citizenship. First, in the account of Dobson there are only negative duties (complying with the sustainable footprint), whereas in Bell’s account there are both negative (obeying laws) and positive duties (promoting laws). Second, in Dobson’s account one should realize justice in one’s own life, whereas in a liberal account justice is realized by means of institutions. Third, Dobson’s environmental duties may be allconsuming, whereas Bell puts forward a ‘cost proviso’ to prevent the possibility of an allconsuming duty. The main reason behind these differences is that liberals attribute great value to institutions in mediating rights and duties among citizens, while Dobson shifts attention from institutions to individual responsibility. 3 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship Within the debate on what we should do in our private live regarding environmental problems, there tend to be two camps. On the one hand, some stress individual responsibility in reducing the overall environmental impact. The idea behind this position is straightforward: since all environmental damage is derivable from individual consumption behaviour, it is clear that changing this behaviour will change the overall environmental impact. On the other hand, some emphasize institutional solutions. The idea behind this position is as straightforward as beyond the former position: if I am the only person who chooses to behave environment-friendly, the overall contribution will be negligible and my sacrifice will be useless. Both positions seem to hold something valuable: the importance of both lifestyle and of institutions. The approach of Bell will allow us to take a more nuanced position between these two camps. Until now we have seen two elements relevant for the examination of private liberal duties. First, liberal citizens have ‘personal rights’, namely they are free to make choices in their everyday life about how they affect the environment. Second, liberal citizens do not have the duty to realize overall justice by means of lifestyle, but rather have the duty to obey and to promote just institutions. These two elements seem to suggest that the liberal citizen does not have private duties. However, Bell states that there are two ways of conceiving private environmental duties within liberalism. First, private pro-environmental actions might be the best way of promoting just arrangements. ‘In so far as private pro-environmental actions are 8 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship necessary or effective mains of promoting changes in law and policies, liberal environmental citizens (acting on their duty to promote just arrangements) may have a duty to perform them’ (Bell 2005: 190). Second, there may be some private pro-environmental actions that a liberal state should support and encourage but the enforcement of such actions by law could possibly violate fundamental liberal rights. In such cases, an appropriate response of the state might be a democratic declaration of a non-enforceable ‘citizen’s duty’ (Bell 2005: 190-2). In the following points, I will go more deeply into these two private duties. According to me, the first private duty is a positive private duty, while the second one is a negative private duty. The reason why I think it is necessary to consider them separately is that the distinction private/public is different for both private duties. In the case of positive private duties I will consider the potential impact of the personal lifestyle, while in the case of negative private duties I will go into the value of privacy; I start with the latter. 3.1 Negative private duties Some private pro-environmental actions should be supported and encouraged by the liberal state, but the enforcement by law, nevertheless, could be undesirable because of a violation of basic liberal rights. In this case, according to Bell, a declaration of a non-enforceable ‘citizen’s duty’5 might be an appropriate solution. If the declared duty is the outcome of a democratic decision-making process, it might be reasonable expected that these citizens’ duties would have some motivational force for good liberal citizens. It may look like a cheap option because of the absence of enforcements cost but ensuring compliance to these duties might involve substantial facilitation, promotion and education costs (Bell 2005: 191-2; 2004: 15). These duties are negative duties, since it are duties to comply with existing institutions. However, it is not completely clear why Bell calls these duties private. The distinctive characteristic of these duties, compared with the negative duties discussed earlier, is that they are not enforceable by law. Why are they not enforceable? Bell gives the following example about recycling: ‘if the enforcement of a law is likely to be impossible without serious invasion of citizens’ privacy, as might be in the case of compulsory recycling, the balance of reasons may not support law making. There may be many things that a liberal state should do to promote (household) recycling: from requiring local authorities to provide kerbside collection through charging households for collection of non-separated waste (for example, by total volume) to implementing educational programmes promoting recycling. However, there may be some things a liberal state should not do, for example giving someone the right to go through people’s refuse to check that they have separated out all of their recyclable material. This may compromise the liberal concern for privacy too much’ (Bell 2005: 191) 5 Non-enforceable duties are not an uncommon feature of liberal theories, for instance the duty of civility and the virtue of public reasonableness. 9 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship I think, however, that privacy is more than just an example. It is probably because of the value of privacy that duties are duties non-enforceable and, therefore, it is the protection of privacy that makes the duties ‘private’6. Why should we protect privacy? Individuality is not only threatened by political coercion, but also by the omnipresent pressure of social expectations. ‘The presence of others can be distracting, disconcerting, or simply tiring. Individuals need time for themselves, away from public life, to contemplate, experiment with unpopular ideas, regenerate strength, and nurture intimate relationships’ (Kymlicka 2002: 394). The basic liberal motivation for respecting privacy is the value of having some freedom from distraction and from incessant demands from others, and the value of having room to experiment with unpopular ideas and to nourish intimate relationships (Kymlicka 2002: 398). In this paper, I am interested in the potential conflict between privacy and environmental-unfriendly behaviour, especially consumption behaviour: in which cases is privacy important enough to prevent the state from steering environmental-unfriendly behaviour? This I will examine by looking successively at three dimensions of privacy, namely decisional, informational, and local privacy (Roessler 2006). First, decisions regarding consumption may be important in forming one’s own identity and self-representation and therefore one should be free to take these decisions (decisional privacy). Nonetheless, the choice of buying product A rather than B does not have the same far-reaching for the way we would like to live as, for instance, choices about sexuality and procreation. Therefore, it seems acceptable that the state, in order to achieve environmental protection, influences decisions regarding consumption, for example, by means of taxes. The steering of consumption behaviour does not necessarily imply a significant reduction of the freedom of choice. Of course, some products are forbidden because of their harmful nature, but this does not generate a serious conflict with decisional privacy since the prohibition has the some goal as privacy, namely protection of autonomy (e.g. health). Secondly, consumption can create privacy problems if information about consumption behaviour is stored (informational privacy). The storage of such information could be used for environmental policy aims. For instance, instead of raising the price of certain products, one might settle the account afterwards: all purchases are count up in order to determine the total environmental cost. However, this seems both ineffective as undesirable. On the one hand, it probably is ineffective because the incentive of environment-friendly behaviour is situated after the moment of purchasing. On the other hand, it is undesirable because it requires that almost all consumption behaviour is registered. There would be an enormous amount of stored information which cannot be controlled by the individuals concerned. This potentially conflicts with the requirement of informational privacy, namely keeping knowledge that others have under control: ‘people want to have control of their own self-presentation; they use the information others have about them to regulate their relationships and thus the roles they play in their various social spaces’ (Roessler 2006: 705). Because of informational privacy, environmental policy measures cannot be based on aggregative consumption 6 The problem of public and private is often thought to be a boundary problem. The task of formulating clear boundaries, however, has proven to be very complex; see: Steinberger, Peter J. (1999). Public and Private, Political Studies 47: 292-313. 10 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship measures such as the ‘ecological footprint’. On a macro-level such measures are useful, but on the individual level they are undesirable because of the amount of information that must be stored. Thirdly, there is a dimension of privacy tied to a particular area, namely one’s own home (local privacy). People need the possibility to withdraw within their own home, to do what they want, unobserved and uncontrolled. It is this dimension of privacy which potentially conflicts with the supervision of environmental-unfriendly behaviour (consumption). However, since the moment of purchasing is already passed when a product enters the private realm, the potential conflict is limited to the use of the products and services. In such cases, the state can declare non-enforceable duties. In sum, negative private duties of liberal environmental citizenship are ‘negative’ since they are about complying with just arrangements. They are ‘private’ since the reason why they are not enforceable is the protection of privacy and especially of local privacy. 3.2 Positive private environmental citizenship duties According to Bell, there is another reason why a liberal can endorse private environmental actions, namely private pro-environmental actions might be the best way of promoting just arrangements. Bell gives again the example of recycling: ‘High levels of voluntary recycling (despite the difficulty) might be the clearest sign to a government that there would be a popular support for public spending on improved recycling facilities. Recycling their waste might be the most effective contribution that liberal environmental citizens can make to promoting just environmental laws and policies’ (Bell 2005: 190). Since these proenvironmental actions promote (non-existing or threatened) just arrangements, I will call these duties positive duties. Because the motivation behind these duties is the promotion of institutions and not the realization of justice by means of private actions, these duties are liberal. It is, however, not clear why these duties count as private. In the case of positive private duties, the border between public and private cannot be the non-enforceability of law since positive duties are about non-existing institutions. Where should we draw the line between public and private in the case of positive duties? On the one hand, private actions are at least to be distinguished from classical political actions, such as voting and demonstrations. On the other hand, in contrast with negative private duties, it seems that positive private duties are not limited to the domain of one’s home, the domestic sphere (cf. local privacy). Bell’s example, recycling, takes place in the domestic sphere, but other examples are conceivable, for instance, using public transportation as a mean of promoting sustainable transportation policies. So, it seems that, in the case of positive duties, the distinction public/private is situated between the political and the domestic domain, namely somewhere in the ‘social’ or ‘cultural’ domain. According to me, the following distinction may be illuminating: the public positive duties encompass a broad interpretation of political actions, whereas the private positive duties encompass the rest, namely the non-political actions. I try to clarify these two categories. First, a broad interpretation of political actions includes, on the one hand, classical political actions (voting, 11 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship demonstrations, letters to MPs, petitions, etc.) which are aimed at influencing the classical political system (political parties, parliament, government, etc.). On the other hand, a broader interpretation of political actions makes room for actions of which the intentions are directed towards social change in a more general sense, namely change in other people’s behaviour/opinions and change of institutions. Examples of such actions are supporting an environmental organization, participating in a consumer boycott, trying to convince friends of an opinion, etc. Such actions, a broad interpretation of political actions, I would call public positive actions. Their distinctive characteristic is that they are mainly directed towards social change. Consequently, private positive actions are actions that are not mainly directed towards change, but are mainly oriented towards other goals. For example, I buy organic vegetables because I want to have food. After deciding that I would like to buy vegetables, I could take the mode of production into account. Another example, I take a train to Brussels, not to support the public transportation system, but rather to get to Brussels. Nonetheless, since I need to get to Brussels I could support public transportation at the same moment. The main focus of the action is not social change; such change is a, possibly intended, side effect7. The distinction between public and private for positive actions, respectively actions mainly or not mainly directed towards change, may seem arbitrarily8. This distinction is, nonetheless, in line with the notion of a positive duty, namely the duty to promote just arrangements, or, in other words, the duty to undertake actions which are directed towards just changes of institutions. The distinction between public and private positive actions (duties) is relevant because liberals seem to deny the possibility of private positive duties. Liberals see the promoting of justice as a burdensome activity (instrumental vision on duties) and, therefore, they tend to think of such promoting only in a direct way (public positive duties). However, this ignores the fact that such promoting can be a ‘side-effect’ of private behaviour (private positive duties). So, the question we have to consider is in which way the personal lifestyle (the aggregate of private actions) can contribute to the promotion of just institutions. I resume the example of Bell: ‘High levels of voluntary recycling (despite the difficulty) might be the clearest sign to a government that there would be a popular support for public spending on improved recycling facilities’ (Bell 2005: 190). (1) This is a first, direct way: lifestyles can motivate the government to design institutions that facilitate the individual behaviour. (2) There is, secondly, a more indirect way: lifestyles can motivate other people to adopt parts of their lifestyles and the state can, subsequently, respond to the total number of adherents of the lifestyle. The copying of lifestyle elements can happen in two ways. (2a) On the one hand, I 7 A consumer boycott is a border case. I have put consumer boycotts in the category of public positive actions since such actions (non-buying of a specific product) are mostly aimed at realizing a political demand. 8 One could ask whether it would not be better to specify private positive actions simply as ‘consumption’. Both interpretations (consumption; not mainly directed towards social change) will mostly coincide with each other, but the category of consumption encompasses, nevertheless, less because some relevant private actions are difficult to term as consumption, for example walking in a forest, having dinner at home with friends, participating on internet forums, cycling to one’s office are, etc. 12 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship could find someone’s lifestyle attractive and look at that lifestyle as an example for me (direct way). (2b) On the other hand, the influence can be more indirect, namely the behaviour of people can influence norms and status9 (indirect way). For example, if more people choose for a particular action, this action may become more socially acceptable. I will try to illustrate this direct and indirect way by using Horton’s empirical research of everyday life among green activists (Horton 2006). First, I start with the indirect way (cf. 2). Horton’s study shows that environmental behaviour is not primarily learned through education, bur rather learned though informal contacts with others, via ‘cultural diffusion’. Green activists create an own cultural world with culturally specific behaviours and understandings and these green cultural codes can be learned steadily, producing a green lifestyle. Second, an example of the direct way (cf. 1) could be the living without a car of green activists. The car’s absence has important effects on everyday life: ‘the geographies, and thus socialities, of green activists tend to shrink toward the local. Carlessness produces compact lives, with the spatial ranges afforded by the practices of walking and bicycling configuring the very contours of this local’ (Horton 2006: 139). This restructured everyday live requires conditions that enhance the possibilities of such a lifestyle, for instance small shops local instead of out-of-town supermarkets. Activists will undertake actions to promote a spatially dense structure, but their way of living will also function as a stimulus for policymakers and the market. In sum, actions that are not mainly directed at social change (private actions; personal lifestyle) may have as a side-effect social change, namely the promotion of just institutions (positive duties). However, liberals want to minimize the interference in the personal lifestyle, since they see freedom as a condition for leading a rewarding life (see above) and, therefore, duties are seen as an impediment to this conditional freedom. This is why duties should be minimized by selecting the most effective and efficient ones. Therefore, the preference is mostly given to public positive duties. Nonetheless, there may be examples where private actions are a necessary or effective means of promotion just institutions. ‘In so far as private pro-environmental actions are necessary or effective means of promoting changes in law or policies, liberal environmental citizens (acting on their duty to promote just arrangements) may have a duty to perform them’ (Bell 2005: 190). In a conference paper, Bell mentions J.S. Mill’s idea of ‘the moral coercion of public opinion’; Bell suggests that such ‘informal social pressure’ can play a central role in understanding environmental citizenship (Bell 2003: 12-4). 9 13 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship 4 Summary of liberal environmental duties: examples Overview: duties of liberal environmental citizenship Liberal versus non-liberal Negative versus private duties approach Public versus private duties Public negative liberal duties (enforceable laws) Negative liberal duties example 1 (complying with existing just institutions) Private negative liberal duties (non-enforceable laws (because of local privacy)) example 2 Public positive liberal duties Liberal duties (behaviour mainly directed towards social change) (realizing justice by means of institutions) Positive liberal duties (promoting of non-existing just institutions) example 4 Private positive liberal duties (behaviour not mainly directed towards social change) Condition: lifestyle is a necessary of effective means of promoting just institutions example 5 & 6 Non-liberal approach (realizing justice in one’s own life) example 3 In the table above, an overview of the different duties discussed in this paper is presented. Here, I will not repeat all the definitions, but I will present six examples in order to illustrate the given definitions. At the same time, I hope these examples demonstrate the relevance of such a classification. I will give six examples: 1. Should I put my litter in a (costly) refuse bag that will be collected, or can I dump my litter somewhere in a forest? This is a question about public negative duties. In the most countries, there is an enforceable law that prohibits illegal dumping. If the law was passed through democratic procedures, we have as good liberal citizens the duty to comply with the law; of course, it may be difficult to enforce the law, but this does not change the nature of the duty. 2. Should I separate my litter, or can a put everything in one refuse bag? This question is different from the previous one because there is a problem of enforceability. The enforcement of a law that compels the separation of household waste in one’s home probably would require a violation of local privacy, for instance, by inspection of the content of one’s refuse bag, or, even worse, by camera surveillance. In this case, the government could declare a ‘citizen’s duty’ to separate household waste. If the declared 14 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship duty is the outcome of a democratic decision-making process and if it is seen as necessary in order to realize the policy-aims, then the good liberal citizen has a duty to comply with the declared duty. ‘The idea of explicitly non-enforceable political duties recognises the capacity of citizens to act justly even when there is no threat of punishment for unjust actions’ (Bell 2006: 191). 3. Should I take a shorter shower, or can I shower as long as I like? (i) If shower time is reduced in order to reduce the total consumption of water in the world, then the reduction of shower time cannot be a liberal duty (non-liberal approach). For the distribution of justice, liberals point at institutions. (ii) Could it be a negative duty? Can something like this be regulated by means of a law? The enforcement of a law requiring reduced shower time inevitably violates local privacy, so it cannot be a question of a public negative duty. (iii) Should the government declare a citizen’s duty (private negative duty)? Probably, there are more effective means of realizing a reduction of the total water consumption, for instance, by subsidizing water saving showers, or by raising the price of water. Therefore, it would not be necessary to declare a citizen’s duty in this case. (However, the situation may be different in the case of ‘squandering’ water, for instance, leaving the tap running without making use of the water. This would be more an example of irrationality then of personal preference – the desire of taking a longer shower could be, by contrast, a personal preference. ‘Not squandering water’ could be a citizens’ duty to declare.) (iv) Is it possible to interpretate the shorter shower as a positive duty? It is clearly not a public positive duty, since the action is not mainly directed towards social change. (v) Finally, could it be a private positive duty? Also this option we have to reject. It seems difficult to imagine that strictly private behaviour, such as the duration of a shower, will contribute to the promotion of just institutions, especially since such behaviour is invisible, both for other people and for the state. In sum, the duty to take a shorter shower cannot be a liberal duty. Of course, if a specific act is not a duty, one is free to perform it anyway. For example, if someone thinks it is really valuable to take a shorter shower, one is, from a liberal point of view, free to do so. There are two possible motivations. First, taking a shorter shower could be part of one’s conception of the good. For example, a shorter shower is seen as healthier or more pleasant. Second, the person may not share the liberal vision on politics: one might think that justice should not be realized by means of institutions (liberalism), but that a just distribution should be realized on the individual level, by means of individual responsibility (de-politicisation). However, these reasons make it difficult to demand the action from others (since it relies on particular conceptions of the good). One can try to convince others of one’s own conception of the good or of politics, but it seems difficult, if not impossible, to speak of a duty. 4. Should I sign a petition for a law that settles limits to air pollution, or can I turn from such a petition? If the proposed law is a non-existing just institution and a petition would be a means of promoting such an institution, the signing of the petition might be a public positive duty of a good liberal citizen. 5. Should I reduce my consumption of meat, or can I eat meat as much as I would like to? If the reason for the reduction is the moral wrongness of killing animals, this cannot be a political liberal duty, since it relies on a specific conception of the good (vegetarianism). 15 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship However, it could be a private positive duty if the following conditions are satisfied: (i) the reduction of meat consumption must relate to justice. This relation can exist, for instance, when meat production (inefficient food production) puts so much pressure on the environment that the satisfying of basic needs becomes problematic; (ii) the reduction of meat consumption must be realized by means of institutions; (iii) the private action, eating less meat, must be a necessary or effective way of promoting institutions. A raising number of vegetarians could be a sign for the government to enhance the conditions for vegetarian consumption – for instance, the requirement that all restaurants should include vegetarian meals into their menu. Since these three conditions might be fulfilled, reduced meat consumption is not necessarily excluded from the scheme of liberal duties. 6. Should I buy fair trade coffee, or can I buy any other coffee? The answer on this question is similar as for the previous question: to be a private positive duty several conditions should be fulfilled, namely: the private action should be a necessary or effective mean to promote just institutions. However, there is an important difficulty in this example which was less clear in the other examples, namely: is it, in this case, possible (or desirable) to realize justice by means of institutions. In the case of fair trade, it is obvious that a just institution would go beyond the legislative powers of the national state. I return to this in the next, final section. 5 Discussion I hope the previous examples have demonstrated both the content and the relevance of the classification of liberal duties. However, several important questions and problems are inevitably situated beyond the scope of this paper. Because of their importance, I will go through four such issues, which can initiate further research. First, this paper focused on which duties should be fulfilled. However, since liberals see duties as burdensome (cf. instrumental interpretation), the question could be raised why one would fulfil one’s liberal duties. Liberals offer a two-level response for this question. First, liberals assume that citizens have a sense of justice. Second, the social unity based on principles of justice is too thin and, therefore, must be further strengthened by a shared sense of nationhood (liberal nationalism) (Kymlicka 2002: 331). However, the question is whether these reasons are sufficient to motivate people to fulfil their liberal environmental duties? The two answers offered by liberal nationalism are probably insufficient, especially since there is inevitably a cosmopolitan element in environmental citizenship, namely the satisfying of basis needs. Secondly, the state may not have sufficient power to enforce certain laws. A substantial part of power is moving away from the classical political centre towards other part of society (science, economics, media, etc.)10. Since liberal theory lays emphasis on legal institutions, it 10 This thesis is extensively elaborated in the work of the German sociologist Ulrich Beck (see especially Beck 1997). 16 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship has difficulties to think about institutions in a more general, sociological sense (e.g. norms, economic laws, status, scientific developments, etc.). The incorporation of such norms would strongly change the interpretation of the duties presented in this paper: if non-legal institutions are crucial for a just distribution, there will be more cases where lifestyle elements count as a positive duty11. Thirdly, one could ask whether the two legitimate sources of just environmental institutions are sufficient for an environmental approach. All environmental protection that transcends the requirement of satisfying the basic needs of current and future generations is left to the democratic discussion between reasonable comprehensive doctrines. Fourthly, the given example of the shower is, of course, provocative since it has two particular characteristics: first, it is socially invisible behaviour and therefore it cannot influence the opinions of others, and second, it is a kind of action that fits the liberal instrumental approach of duties, namely the duty is experienced as burdensome. However, a lot of ‘good’ environmental behaviour is not necessarily experienced as burdensome. For example, people can like cultivating home-grown vegetable, or walking and cycling, or travelling by train, or living frugal and working less, or using natural shampoo, etc. People can prefer these actions over other environmental-unfriendly actions, even without taken the environmental consequences into account. This, I think, is a very attractive idea for a green political theory, namely the overlap between lifestyle elements of a ‘green’ comprehensive doctrine and lifestyle elements that have environmental-friendly consequences. 6 Conclusion According to me, the contention that liberalism cannot think of private duties is, as I have tried to demonstrate in line with Bell’s ideas, mistaken. Both in the case of negative and of positive duties, there is room of conceiving private duties. First, even if our action is not mainly directed at social change (private actions), we might have a liberal duty to perform this action (positive private duty), namely if the action is a necessary or effective means of promotion just institutions. Second, even if a law is non-enforceable because of local privacy (private sphere), we might have a liberal duty to perform the non-enforceable action (negative private duty), namely if this action is declared by the state as a citizen’s duty. This paper demonstrated that environmental problems challenge the employed distinction between the public and the private sphere within a political liberal account of citizenship. If liberalism is to take this challenge seriously, it should take the personal lifestyle into consideration References 11 In this paper there was one exception on the focus on legal institutions: in the discussion about private positive duties there was room for institutions such as norms, but only as an indirect means of promoting legal institutions. 17 Private duties of liberal environmental citizenship Beck, Ulrich (1997). The Reinvention of Politics. Rethinking Modernity in the Global Social Order. Cambridge: Polity Press. Bell, Derek R. (2002). ‘How can Political Liberals be Environmentalists?’, Political Studies, 50/4: 70324. Bell, Derek R. (2003). Environmental Citizenship and the Political. Paper presented at ESCR Seminar Series on ‘Citizenship and the Environment’, Newcastle, 27 October. Bell, Derek R. (2004). Justice, Democracy and the Environment: A Liberal Conception of Environmental Citizenship. Paper presented at PSA Annual Conference, Lincoln, 6-8 April 2004. Bell, Derek R. (2005). ‘Liberal Environmental Citizenship’, Environmental Politics, 14/2: 179-194. Dahrendorf, Ralf (1994). ‘The Changing Quality of Citizenship’, in Bart Van Steenbergen (ed.), The Condition of Citizenship. London: Sage, 10-9. DeCew, Judith (2006). ‘Privacy’, in Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2006 Edition), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2006/entries /privacy/>. Dobson, Andrew (2003). Citizenship and the Environment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dobson, Andrew (2006). ‘Citizenship’, in Andrew Dobson and Robyn Eckersley (eds.), Political Theory and the Ecological Challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 216-31. Dobson, Andrew and Bell, Derek (eds.) (2006). ‘Introduction’, in Andrew Dobson and Derek Bell (eds.), Environmental Citizenship. Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press, 1-17. Horton, Dave (2006). ‘Demonstrating Environmental Citizenship? A Study of everyday Life among Green Activists’, in Andrew Dobson and Derek Bell (eds.), Environmental Citizenship. Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press, 127-50. Kymlicka, Will (2002). Contemporary Political Philosophy. An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Leydet, Dominique (2006). ‘Citizenship’, in Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2006 Edition), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2006/entries /privacy/>. Rawls, John (1999(1971)). A Theory of Justice. Revised Edition. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press. Rawls, John (1993). Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press. Roessler, Beate (2006). ‘New Ways of Thinking about Privacy’, in John S. Dryzek, Bonnie Honig and Anne Philips (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 696-712. Saward, Michael (2006). ‘Democracy and Citizenship: Expanding Domains’, in John S. Dryzek, Bonnie Honig and Anne Philips (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 400-19. Van Steenbergen, Bart (1994b). ‘Toward a Global Ecological Citizen’, in Bart Van Steenbergen (ed.), The Condition of Citizenship. London: Sage, 142-52. 18