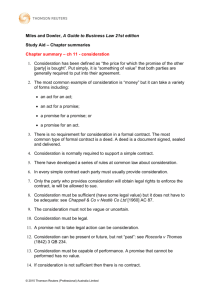

Contracts I

advertisement