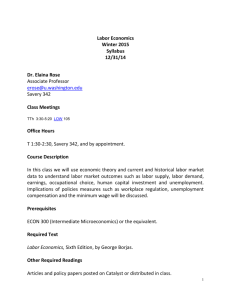

Syllabus - Brandeis University

advertisement

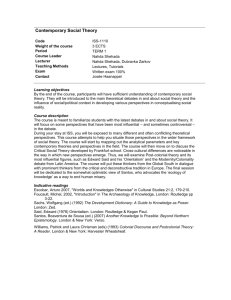

THE HELLER SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL POLICY AND MANAGEMENT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY HS372B. ECONOMIC THEORY AND SOCIAL POLICY Spring 2014 Christine Bishop Office: Schneider 214 Phone: ext. 6-3942 E-mail: bishop@brandeis.edu MPP Students: Wednesdays, 2:00-4:50 Ph.D. Students: Wednesdays, 1:00-3:50 Schneider G1 Barry L. Friedman Office: Schneider 205 Phone: ext. 6-3783 E-mail: bfriedman@brandeis.edu TAs Kim Lucas, klucas@brandeis.edu Henrietta Awo Osei-Anto hawo@brandeis.edu Course Description: This course introduces concepts of economic analysis that can be applied in the analysis of social policies. Familiarity with basic microeconomic concepts as in HS245f would be helpful. The main part of the course deals with microeconomics with basic tools being introduced in the context of labor markets. It begins with supply and demand, focusing on the labor market. Then it goes into the numerous complications that arise in studying markets. The analysis leads to a consideration of inequality and the factors that can contribute to it. On the policy side, the course will deal with welfare policy, human capital policy, the problems of disadvantaged groups, economic policies to deal with discrimination, and unemployment. It also considers labor market institutions such as unions. Course Objectives: The student should come away with a basic comprehension of microeconomic tools and processes. The student should learn about tools that can be useful in evaluating social policies and should gain an understanding of the economic issues in selected social policy areas. Course Structure: Each week, there will be a core session from 2:00 to 3:50 for the whole class, which will develop the basic concepts and theory for the week. There will be an additional hour before this for Ph.D. students and after for MPP students. MPP group (4:00-4:50): Each week a team will choose a policy topic related to the week’s core topic and prepare a 2-page background statement on it, including analysis of the problem from an economics perspective. The statement should not only present background, but also recommend a solution, or at least some policy alternatives. In consultation with instructors, the team will select readings giving background on their policy topic. The team will lead 533574087 1 1 the discussion. Ph.D. group (1:00-1:50): In most weeks, a group of students will give a presentation stimulated by the articles marked with a § on the reading list for that week. The presentations might consider the theory in the articles, research methods, research conclusions, and policy recommendations. The presentations should inform others who may not have read the articles, should be interesting to them, and should stimulate discussion. In weeks with no presentation, there will be a group discussion related to the core topic or readings of the week. Course Requirements: The following activities are required for the course. 1. Presentations by MPP students. Required. 2. Presentations by Ph.D. students. Required. 3. Homework assignments. In this course, new technical concepts will come up at nearly every session. In order for students to keep up and to master the concepts, there will be technical exercises in most weeks during the semester. Problems will be assigned at the beginning of the week. At the end of the week, answers will be distributed. Students will grade their own exercises, correct them, and hand them in. A student will receive 5 points for every homework assignment turned in. 4. There will be a midterm exam and a final exam, each graded on a scale of 100 points. Course Reading: The following book will be available in the bookstore: George J. Borjas, Labor Economics, McGraw Hill Irwin, 6th edition. If you have earlier editions, they are OK. There are also many readings on the syllabus that will be available on LATTE. In general, these are difficult. But they also illustrate the way economists formulate and test the hypotheses necessary to evaluate social policies. Provisions for Feedback: Weekly homework assignments will be self-graded. Each of the other written assignments will be graded and returned. The grade for the course will be Satisfactory or Unsatisfactory for Ph.D. students and a letter grade for students in other programs. Academic Integrity: Academic integrity is central to the mission of educational excellence at Brandeis University. Each student is expected to turn in work completed independently, except when assignments specifically authorize collaborative effort. It is not acceptable to use the words or ideas of another person- be it a world-class philosopher or your lab partner – without proper acknowledgement of that source. This means that you must use footnotes and quotation marks to indicate the sources of any phrases, sentences, paragraphs or ideas found in published volumes, on the internet, or created by another student. Violations of university policies on academic integrity, described in Section 3 of Rights and Responsibilities, may result in failure in the course or on the assignment, and could end in suspension from the University. If you are in 533574087 2 2 doubt about the instructions for any assignment in this course, you must ask for clarification. Notice: If you have a documented disability on record at Brandeis University and require accommodations, please bring it to the instructor’s attention prior to the second meeting of the class. If you have any questions about this process, contact Mary Brooks, disabilities coordinator for The Heller School at x 62816, or at maryeliz@brandeis.edu Course Schedule and Readings (tentative) 1. January 15 Introduction to the labor market. This session reviews supply and demand in the context of labor markets. Ways of measuring the labor force are introduced. In the MPP and Ph.D. sections, current economic conditions will be discussed. 1. Borjas, chapters 1, 2. 2. January 22 Labor supply. The supply side of the market is examined in more detail. The technical tool of indifference curves is introduced and used to derive a labor supply curve. Various applications are discussed in the text. Measuring macroeconomic variables (GDP and its components, inflation) for PhD and MPP sections. 1. Borjas, chapter 2. 2. Mankiw, Principles of Macroeconomics, chapters 22 and 25. 3. January 29 More on labor supply and applications. Measuring labor market indicators for PhD and MPP sections. 1. Borjas, chapter 2 2. Bureau of Labor Statistics, How the Government Measures Unemployment. 3. Claudia Goldin, “The Quiet Revolution that Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family,” 2006 Ely Lecture, January 2006. 4. Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, “Female Labor Supply: Why Is the US Falling Behind?” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 103(3) 2013, pp. 251-256. 4. February 5 Labor supply, welfare, and family 1. Borjas, chapter 3 , continued. 2. Background/ overview: Moffitt, R.A. (2002). Welfare Programs and Labor Supply. Handbook of public economics. Volume 4. A. J. Auerbach and M. Feldstein, ed.: Handbooks in Economics, vol. 4. Amsterdam; London and New York: Elsevier Science, North-Holland: 2393-2430. Good review using the tools we are learning. 3. Background/ overview: Bitler, M.P. & Hoynes, H.W. (2010). The State of the Social Safety Net in the Post-Welfare Reform Era. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 71-127. DOI: http://www.brookings.edu/about/projects/bpea/past-editions. 533574087 3 3 4. § David Card and Rebecca Blank, “The Changing Incidence and Severity of Poverty Spells among Female-Headed Families,” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings,” May 2008, pp. 387-391. 5. § Marianne Bitler, Jonah Gelbach, Hilary Hoynes, “What Mean Impacts Miss: Distributional Effects of Welfare Reform Experiments,” American Economic Review, September 2006, pp. 988-1012. 6. § Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Emmanuel Saez, “Using Differences in Knowledge Across Neighborhoods to Uncover the Impacts of the EITC on Earnings,” American Economic Review, 103(7), October 2013, pp. 2683-2721. 5. February 12 Labor demand. Marginal productivity theory is reviewed as a way to understand more about the demand for labor. 1. Borjas, chapter 3 . Minimum Wage 2. § Background: David Neumark and William Wascher, “The Effects of Minimum Wages on Employment,” Minimum Wages, MIT Press, 2008, chapter 3, pp. 37-89. 3. § David Card and Alan Krueger, “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania,” American Economic Review, September 1994. 4. § David Neumark, Mark Schweitzer, William Wascher, “The Effects of Minimum Wages on the Distribution of Family Incomes: A Nonparametric Analysis,” Journal of Human Resources, Fall 2005, pp. 867-894. February 17-21. Midterm Recess. No Class. 6. February 26 Labor market equilibrium. Since there are many labor markets, individuals will consider moving between them. Given the exit and entry of workers in particular markets, this session considers the determinants of equilibrium across labor markets. 1. Borjas, chapter 4. Compensating differentials. This session introduces the concept of compensating wage differentials, which looks differences in job characteristics as an explanation of differences in wages. 2. Borjas, chapter 5 3. § England, P., Budig, M. & Folbre, N. (2002). Wages of virtue: The relative pay of care work. Social Problems, 49, 455-473. 4. § Hersch, J. (2011). Compensating Differentials for Sexual Harassment. American Economic Review, 101, 630-634. DOI: http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/. 5. § Link, C.R. & Yosifov, M. (2012). Contract Length and Salaries Compensating Wage Differentials in Major League Baseball. Journal of Sports Economics, 13, 3-19. DOI: http://jse.sagepub.com/content/by/year. 533574087 4 4 6. § McCrate, E. (2005). Flexible Hours, Workplace Authority, and Compensating Wage Differentials in the US. Feminist Economics, 11, 11-39. DOI: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfec20. 7. § Miller, R.D., Jr. (2004). Estimating the Compensating Differential for EmployerProvided Health Insurance. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 4, 27-41. DOI: http://link.springer.com/journal/volumesAndIssues/10754. Who pays for employer-sponsored health insurance, the employer or the employee? Midterm Exam Distributed. 8. March 5 Compensating differentials, continued. Human capital. Human capital investment creates differences among workers. It is an important contributor to individual earnings and the productivity of the economy. But it also contributes to the inequality in wages. 1. Borjas, chapter 6. 2. Claudia Goldin, “The Human Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past,” Journal of Economic History, June 2001. 3. Claudia Goldin, Lawrence Katz, and Ilyana Kuziemko, “The Homecoming of American College Women: The Reversal of the College Gender Gap,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2006, pp. 133-156. Human Capital Policy for Disadvantaged Groups 4. § Cullen, J.B., Levitt, S.D., Robertson, E. & Sadoff, S. (2013). What Can Be Done to Improve Struggling High Schools? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27, 133-152. DOI: http://www.aeaweb.org/jep/. 5. § Duncan, G.J. & Magnuson, K. (2013). Investing in Preschool Programs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27, 109-132. DOI: http://www.aeaweb.org/jep/. 6. § Rosenbaum, J.E. & Rosenbaum, J. (2013). Beyond BA Blinders: Lessons from Occupational Colleges and Certificate Programs for Nontraditional Students. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27, 153-172. DOI: http://www.aeaweb.org/jep/ 7. § Dave, D. M., H. Corman and N. E. Reichman (2012). "Effects of Welfare Reform on Education Acquisition of Adult Women." Journal of Labor Research 33(2): 251282. Midterm Exam Due. 8. March 12 Wage structure. This session considers the distribution of wages. It looks at ways to measure inequality. It begins to put together various sources of inequality, which might explain the wage structure. 1. Borjas, chapter 7. 2. Peter Gottschalk and Sheldon Danziger, “Inequality of Wage Rates, Earnings, and Family Income in the United States, 1975-2002,” Review of Income and Wealth, June 2005, pp. 231-254. 533574087 5 5 3. Jonathan Haskel, Robert Lawrence, Edward Leamer, Matthew Slaughter, “Globalization and U.S. Wages: Modifying Classic Theory to Explain Recent Facts,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2012, pp. 119-140. Income of The Top 1%. Topic for presentations. 4. § Facundo Alvarado, Anthony Atkinson, Thomas Picketty, and Emmanuel Saez, “The Top 1 Percent in International and Historical Perspective,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), Summer 2013, 3-20. 5. § Gregory Mankiw, “Defending the One Percent,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), Summer 2013, 21-34. 6. § Steven Kaplan and Joshua Rauh, “It’s the Market: The Broad-Based Rise in the Return to Top Talent,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), Summer 2013, 3556. 9. March 19 Taxes, Inequality, and Labor Supply. This session introduces basic features of the US tax system. It examines the distribution of income and of taxes. It considers issues in tax reform including effects on equity and on labor supply. 1. Samuel Brown and William Gale, “Tax Reform for Growth, Equity, and Revenue.” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, November 30, 2012. An opinion piece that raises important issues in tax design and reform. 2. Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “How Progressive is the US Federal Tax System? A Historical and International Perspective,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), Winter 2007, 3-24. 3. Michael Keane, “Labor Supply and Taxes: A Survey,” Journal of Economic Literature, December 2011, pp. 961-66. Labor mobility. Low waged workers; intergenerational mobility in income and wealth. Topic for presentations. 4. Background. Pew Charitable Trust, “Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility Across Generations,” July 2012. 5. Background: Website and interactive map: Economics of Opportunity Project http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/ 6. § LaDonna Pavetti and Gregory Acs, “Moving Up, Moving Out, or Going Nowhere? A Study of the Employment Patterns of Young Women and the Implications for Welfare Mothers,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Fall 2001, pp. 721736. 7. § Henry Farber, “What Do We Know about Job Loss in the United States? Evidence from the Displaced Worker Survey, 1984-2004,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives, 2nd Quarter 2005, pp. 13-28. 8. § Gregory Acs, “Waking Up from the American Dream,” Pew Charitable Trust, Sepember 2011. 533574087 6 6 10 and 11. March 26 and April 2. Discrimination. This session examines discrimination in labor markets as another source of earnings inequality, one that is not explained by either differences in jobs or differences in workers. 1. Borjas, chapter 9. Should Taxes on the Rich Be Increased? Topic for presentations March 26. 2. § Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez, “The Case for a Progressive Tax: From Basic Research to Policy Recommendations,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2011, pp. 165-190. 3. § Gregory Mankiw, Matthew Weinzierl, and Danny Yagan, “Optimal Taxation in Theory and Practice,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2009, pp. 147-174. Exclusion and labor markets. Although many populations are excluded by society in some way and suffer discrimination, the processes work differently for different groups. We first consider processes for specific groupsbased on sexual orientation, gender, and race. We look also at policies that have attempted to deal with discrimination. A. Sexual Orientation. Section discussions on April 2 1. Optional. M.V.Lee Badgett, “The Economic Penalty for Being Gay,” chapter 2, and “Costs of the Closet,” chapter 3, Money, Myths, and Change: The Economic Lives of Lesbians and Gay Men, University of Chicago Press, 2001. The first effort to apply economic concepts to the study of discrimination in relation to sexual orientation. 2. § Dan Black, Hoda Makar, Seth Sanders, and Lowell Taylor, “The Earnings Effects of Sexual Orientation,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56(3) April 2003, pp. 449-469. Update after Badgett. Includes good discussion of data problems. 3. § M.V.Lee Badgett, “The Double-Edged Sword in Gay Economic Life? Marriage and the Market,” Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice, 109, 2008, pp. 109-128. 4. § Kristen Schilt and Matthew Wiswall, “Before and After: Gender Transitions, Human Capital, and Workplace Experiences,” B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, Volume 8, Issue 1, Article 39. B. Race and Ethnicity. Section discussions on April 9. 1. § Finis Welch, “Catching Up: Wages of Black Men,” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, May 2003, pp. 320-325. 2. § Arthur Goldsmith, Darrick Hamilton, and William Darity, “Shades of Discrimination: Skin Tone and Wages,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, May 2006, pp. 242-245. 3. § Patrick Mason, “Culture and Intraracial Wage Inequality Among America’s African Diaspora,” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, May 2010, pp. 309-315. 4. § John H. Donahue III and James Heckman, “Continuous Versus Episodic Change: The Impact of Civil Rights Policy on the Economic Status of Blacks,” Journal of Economic Literature, December 1991, pp. 1603-43. 533574087 7 7 5. § Lang, K. and M. Manove (2011). "Education and Labor Market Discrimination." American Economic Review 101(4): 1467-1496. C. Gender. Section discussions on April 23. 1. § Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, “Gender Differences in Pay,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2000, pp. 75-99. 2. § Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, “The Gender Pay Gap,” The Economists’ Voice, June 2007. An update of their previous work. 3. § Claudia Goldin, “The Rising (and then Declining) Significance of Gender,” May 2002. 4. § David Matsa and Amalia Miller, “Chipping Away at the Glass Ceiling: Gender Spillovers in Corporate Leadership,” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, May 2011, pp. 635-639. 12. April 9 Unions. Incentive Pay. This session looks at important labor market institutions to see how they affect the functioning of the markets. We look at unions and then at the mechanisms used to set pay. 1. Borjas, chapter 10, Labor Unions. 2. Borjas, chapter 11, Incentive Pay. 3. § Hirsch, B.T. (2004). What Do Unions Do for Economic Performance? Journal of Labor Research, 25, 415. 4. § Dresser, L. & Bernhardt, A. (2006). Bad Service Jobs: Can Unions Save Them? Can They Save Unions? Justice on the Job: Perspectives on the Erosion of Collective Bargaining in the United States. R. N. Block, S. Friedman, M. Kaminski and A. Levin, ed.: Kalamazoo, Mich.:W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: 115137. 5. § Ichniowski, C. and K. Shaw (2003). "Beyond Incentive Pay: Insiders' Estimates of the Value of Complementary Human Resource Management Practices." Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(1): 155-180. April 15-April 22. Spring Recess. No class. 13. April 23 Unemployment. Unemployment is a challenge to our understanding of markets. This session looks at data and theories related to unemployment. 1. Borjas, chapter 12. Final Exam Distributed April 30. Final Exam Due. No class. 533574087 8 8