Latissimus Dorsi Transfer to Posterosuperior Cuff

advertisement

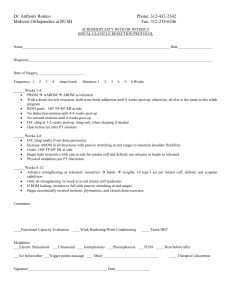

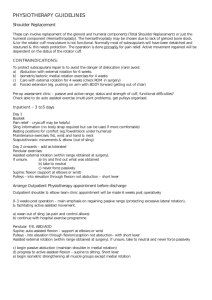

Post-operative rehabilitation guidelines Latissimus Dorsi Transfer to Posterosuperior Cuff Please note that this is advisory information only. Your experiences may differ from those described. A fully qualified Physiotherapist must demonstrate all exercises to a patient. We cannot be held liable for the outcome of you undertaking any of the exercises outlined here independently of direct supervision from the RNOH. Please read these guidelines with consideration to the specific physiotherapy discharge report that will be sent to the physiotherapist concerned. There may be individual variation that is patient specific in which case these general guidelines will have to be modified as appropriate by the physiotherapist. At RNOH, our emphasis is patient-specific, not condition-specific rehabilitation which encourages recognition of those patients who may progress slower than others. We also want to encourage clinical reasoning based on the continuum concept of shoulder rehabilitation i.e. similar rehabilitation tools are used for each shoulder procedure but the time of intervention varies according to the status of the tissues at pre-op, at surgery and the post-op restrictions. Most of our procedures at RNOH have guidelines that fall into categories loosely based on the Matsen classification of shoulder dysfunction rather than having specific guidelines for each of our more established procedures – however, as this particular procedure is often used to supplement another – it is difficult to necessarily generalise and suggest which classification it should be in – therefore, for now, these guidelines stand alone! Our hope is that by providing guidelines and treatment ideas, it will promote an equitable rehabilitation service to all of our patients and improve the overall understanding of the unique challenges that rehabilitation of the shoulder complex presents. Milestone driven Apart from phase one of the post-operative care which is based upon tissue healing times and surgical opinion, these guidelines are milestone driven and designed to provide an equitable rehabilitation service to all of our patients. The time periods documented at the beginning of each phase are purely there as a rough guide. We hope the guidelines will limit unnecessary visits to the outpatient clinic at the RNOH by helping the patient and therapist to identify when specialist review is required. If the patient and the therapist feel that rehabilitation is progressing satisfactorily and there are no concerns, the patient may cancel and re-book their follow up for a later date. Failure to progress or variations from the norm should be the main reason for clinic attendance. Both patients and therapists can book clinic visits by contacting the numbers given in this document. In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science It is essential you contact us if you have any concerns: Physiotherapy Team Occupational Therapy Team Consultant Team Secretaries 020 8909 5820/5519 020 8909 5310 020 8909 5456/5727 Surgical Indications for Latissimus Dorsi Transfer to Posterior Cuff Inability to actively place and hold the arm in a functional position in front of the body at waist level due to lack of active external rotation at the shoulder. - e.g. following Brachial Plexus Injury/Neurological Compromise, Irreparable Massive Cuff Tears. Being unable to place the arm in this position will prevent the ability to achieve the starting positions required for an Anterior Deltoid Programme should it be required. Inability to * “snug” the humeral head on initiation of abduction. This can lead to pain and decreased function in elevation. - e.g. secondary to posterosuperior cuff failure. *“Snugging” of the humeral head is a term we often use to explain the normal subtle movement of the humeral head as it centres towards the glenoid prior to any movement of the GHJ. This action is normally produced by a functioning cuff. It is tested with gently resisted abduction of the shoulder and the “down and in” motion of the humeral head is observed. Possible surgical complications Infection Neurovascular compromise Joint stiffness Failure of the transfer Expected long-term outcome When used to supplement a rotator cuff repair, expected outcome may take 9-24 months to achieve. Post neurological injury/BPL our experience shows that changes can continue to develop for up to 4-5 years post transfer. For patients who have had the transfer to supplement a cuff repair, the expected long term outcome should be similar to that of a standard cuff repair, but the time taken to achieve it will be longer due to the early restrictions and the time taken to re-educate the function of the Latissimus Dorsi muscle. This operation is sometimes undertaken in conjunction with other operative procedures such as Total Shoulder Replacements (TSR) therefore it is imperative that all components and limitations of the surgery are taken into consideration. A standard goal for all patients is to report a pain-free shoulder (other underlying pathology to be considered) that can be held comfortably in neutral rotation at waist level allowing for increased functional activity. Further progress from this stage and long-term functional In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science outcome is dependent on the underlying pathology/neuropathology/additional surgery rather than purely the latissimus transfer itself and it is important that the patient’s goals and expectations are realistic at the outset. In-patient post op care plan The RNOH Shoulder Physiotherapy Service follows this care plan prior to discharge. Goals: 1. To educate the patient on post operative instructions and expected outcomes following surgical procedure – this may include explaining the purpose of an in-patient rehabilitation admission for initiating Phase 2 in the future. 2. To explain the purpose of the patient’s specific support – ie spica or abduction pillow and demonstrate ideal positioning/how to alter and remove components of spica/abduction pillow for exercises - within post-operative restrictions. 3. To ensure patient is safe mobilizing on ward with arm immobilized in spica or abduction pillow and feels they can manage stairs/check they can manage stairs, with arm immobilized (as appropriate). 4. To teach scapular setting and hand/wrist/elbow ROM exercises (where appropriate). 5. To teach and ensure that the patient and/or carers are competent with the post operative exercise programme and can maintain the programme post discharge. 6. To ensure all patients requiring further physiotherapy are given a copy of their outpatient referral prior to discharge and are aware that they can contact the Shoulder Service if local services fail to provide a timely appointment. 7. To fax/send physiotherapy referral with patient specific guidelines and information about accessing generic guidelines to local physiotherapy team (as appropriate). In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science Initial rehabilitation phase one: For Latissimus Dorsi Transfer to Posterosuperior Cuff Discharge – 8 (or 12) weeks (Dependent on patient specific post-op instructions) If additional major surgery was carried out in conjunction with the transfer, the guidelines may vary. The integrity and tension of the graft will drive the decisions regarding Phase One. Goals: 1. Ensure Wound/Tissue Healing (as able, according to method of immobilization – ie spica or abduction pillow). 2. Encourage effective pain control. 3. Ensure patient is safe mobilizing with spica/abduction pillow. 4. Maintain/Increase Passive/Active-Assisted ROM -ranges will be documented on patient specific referral. 5. Initiate scapular control. 6. Continue Isometrics (IR+ER) and eccentric ER -only if documented on patient specific referral. Restrictions: 1. The patient is not to lower the arm from the abduction pillow or remove abduction pillow or spica. 2. No exercises to be carried out, other than those outlined in the post-op plan, that would affect the graft. 3. Exercise should remain relatively pain-free. Education: Patient education on anatomy of shoulder complex, post-op restrictions, progression of short/long term goals in conjunction with guidelines, postural advice/retraining. Milestones to progress to phase two: 1. Adequate pain control. 2. Adequate scapular control. 3. Achieved time specific goals specified on individual referral. Often, to initiate this next phase, the patient will be brought into RNOH rehabilitation ward for one week – especially if they have been immobilised in a plaster spica, if this is not due to happen, please progress…….. In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science Rehabilitation phase two: Approx weeks 8 (or 12) to 9 months Goals: 1. To hold and maintain at least 30 degrees ER with the elbow supported on the abduction pillow (ie with the arm resting at approx 40 degrees scaption). 2. To be able to eccentrically control the arm from 30 degrees ER position on abduction pillow, back to rest on abduction pillow. 3. (After achieving 1 & 2 above) To wean off the abduction pillow, deflating it, lowering the arm on the support, whist ensuring some control is still achievable as the abduction component decreases. 4. To start to use the arm at waist level for functional activity. Restrictions: 1. Where possible, minimize exercises that may exacerbate pain. 2. Once in this phase, even prior to gaining control, the patient can remove the support for washing/dressing etc, but should return to the abducted/neutral rotation position at other times so as not to overstretch the graft, making it harder to gain activity – this resting position can be on an armchair or table at times if the patient prefers. 3. Avoid removing the abduction pillow too quickly – even though the patient will want to be rid of it! Continue using it for resting and exercises until the patient is able to isometrically hold at approx 30 degrees ER so as to avoid stretching the graft and therefore compromising the ability to recruit to the muscle. 4. Avoid GHJ stretching other than to achieve the ranges required for the goals above. Advice: It is important to remember that when working through these very basic stages, the exercises are not about just “strengthening” the muscle – the muscle/tendon transfer itself would have been of adequate quality and strength in it’s previous position and function, and although it has been disrupted and immoblised and therefore weakened, “strengthening” as such, is not the main focus. The important concept is that of developing the neuromuscular control of the muscle in its new roles as an external rotator and posterosuperior stabilizer of the humeral head. Latissimus Dorsi has always worked predominantly as an internal rotator and adductor of the GHJ and as a depressor of the shoulder girdle. In its new role, it will still depress the shoulder girdle and adduct the GHJ, but it now has to externally rotate the shoulder and assist the remaining cuff (if applicable) to “*snug” the humeral head onto the glenoid. You will need to initially get cognitive control of the new role and then eventually, as neuroplasticity takes place, it will hopefully become more automatic. In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science Some ideas to assist the exercise progression: In the 40/45 degrees position on the abduction pillow, assist the ER movement to 30/40 degrees as able and encourage “holding” with the addition of some adduction/depression – i.e. using part of the “old” role to activate the LD muscle, but assist the new ER position – as the patient is able to hold it isometrically, try to decrease the active adduction component. Don’t request a maximum contraction – it is not about “strength” but activating the muscle appropriately – perhaps try “30%” effort as a starting point. Use biofeedback if you have the facility, placed on the belly of the LD transfer, to give visual feedback as to when the transfer is working and encourage the “holding” – even if still supported Use FES in a similar way to the biofeedback, giving sensation feedback as to how to activate the muscle – join in with it. Place a hand on the area to give proprioceptive feedback so the patient knows where the contraction should be happening and can get some feedback. Manually facilitate the adduction/depression component that you are trying to activate whilst the patient “joins in”. Repetition! Repetition! Repetition! Use 30-40 degrees of ER as this is roughly the mid to inner range of the transfer and therefore, from a length-tension relationship point of view, it should be easier! However, if the patient is struggling, vary the degree of ER. Once you have the isometric hold, work on eccentric lowering back to neutral rotation – i.e. back to the abduction pillow – gaining control this way will prevent “hitching”/elevating of the scapula and it appears to gain control more easily than working concentrically. Hydrotherapy can be useful to assist with the upper limb control and also with general scapulothoracic control, core stability etc Education: Patient education about the reasoning behind the exercises and the need for continuing abduction/ER support, ongoing postural education. Milestones to progress to Phase Three: (if this is much sooner than 9 months – please still progress…that is the purpose of milestones rather than specified time periods) 1. To be able to hold the arm at approx 30 degrees ER with the arm resting at approx 40 degrees scaption/abduction. 2. To be able to eccentrically control the arm from approx 30 degrees ER position back to neutral when resting at approx 40 degrees scaption/abduction. 3. To have weaned off the abduction pillow and be using arm at low level for light activities. In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science Once these milestones have been achieved, if there are no other reasons for restricting it, driving can be restarted if the patient feels safe to do so. Rehabilitation phase three: Approx 9 months+ (Dependent on underlying pathology and other rehab requirements) Regardless of whatever additional operation your patient has had, the information below incorporates the final progression of the LD transfer +/- other operations. At this stage –if your patient has also had an additional Total Shoulder Replacement or Rotator Cuff Repair – see “Smooth and Weak” Guidelines for more specific guidance if required, and work through the phases according to the milestones outlined. Goals: For those without an existing, functioning Rotator Cuff: 1. To restore full active range of movement (patient specific). 2. To achieve MMT grade 3/5 from an internally rotated position to neutral rotation at 0 degrees abduction – achieving a comfortable “neutral position”, but not necessarily being able to achieve full MMT grade 3/5 through full passive ER range. 3. To develop automatic control of ER and endurance of appropriate muscle groups (patient specific) and relate to functional tasks. For those without an existing, functioning Rotator Cuff, but a functioning Deltoid: 1. To restore full active range of movement (patient specific). 2. To achieve MMT grade 3/5 from an internally rotated position to neutral rotation at 0 degrees abduction – achieving a comfortable “neutral position”, but not necessarily being able to achieve full MMT grade 3/5 through full passive ER range. 3. To develop automatic control of ER and endurance of appropriate muscle groups (patient specific) and relate to functional tasks. 4. To work through an Eccentric Deltoid Programme and maximize functional range. For those who have had the transfer to supplement an existing cuff/cuff repair: 1. To restore full active range of movement (patient specific). 2. To achieve grade MMT 3/5 through rotation range. 3. To develop automatic control of ER and endurance of appropriate muscle groups (patient specific) and relate to functional tasks. 4. To recruit the LD transfer to achieve “snugging” of the humeral head automatically on the initiation of abduction. 5. To progress Rotator Cuff/Transfer control initially to the exclusion of Deltoid in varying positions through range and without inappropriate In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science muscle patterning (Pecs, Traps, etc) and then to progress control through full functional range with addition of Deltoid. For all patients - try to restore scapulohumeral rhythm, maintain core and postural control and address all other aspects of the kinetic chain as required to maximize function. Restrictions: 1. Where possible minimize exercises that may exacerbate pain. 2. If the patient has an active Rotator Cuff, ensure it is functioning well at a low level and the humeral head is “snugging” into the glenoid prior to progressing to active exercises above shoulder level. Education: Patient education around pacing of activity. Return to sporting activity – initially non contact. Caution to be taken with previously aggravating activities. Ongoing postural education. Normal movement with functional activities. To remind regarding the purpose of the LD transfer for each individual patient so that expectations are realistic. Some ideas to assist the exercise progression (as appropriate): When stretching, start with active-assisted stretches into range – considering the expected outcome as to how much range is going to be needed for long term goals. Maintain and monitor the ER control that has been gained closely as you start to stretch the GHJ as you are now stretching the graft and could lose control if you stretch too quickly. Use capsular stretches as required for anterior and posterior capsule – again, monitoring the active ER gains that have been made and ensuring these are maintained. Use slings and springs or hydrotherapy to offload the arm, allowing low level cuff exercises (as appropriate), now treating the LD transfer as posterosuperior cuff, add resistance and decrease support as control improves. If using therabands, use a maximum strength of a yellow band if you are trying to target just the cuff itself. Monitor the transfer activity during exercises (with biofeedback/palpation) to ensure that it is now activating appropriately as posterosuperior cuff. Still use the concepts of initiating “old” functions of LD while trying to achieve “new” functions to recruit appropriately – as in Phase Two – assisting with manual, visual, proprioceptive feedback and facilitation where required. As the control improves at waist level, incorporate more functional activities to try to make the transition from cognitive control of the graft to automatic control. Use a closed and open chain exercise programme. Address and strengthen LD’s original and ongoing action of scapula depression, GHJ adduction and extension from a flexed position In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science For information on cuff exercises and Anterior Deltoid exercises see “Smooth and Weak” Guidelines and exercise examples on the RNOH web page. Address general core control and proprioceptive deficits - consider Kibler et al, 2001. Principles of Kinetic chain and the incorporation of lower limb exercises. Failure to progress: If a patient is failing to progress, then consider the following: Possible problem Pain Inhibition Action Adequate analgesia Maintain pain free exercises Return to passive stretches if appropriate Slow rehab programme If severe night/resting pain then refer to Shoulder Unit Inability to gain any activity Try exercise ideas outlined in phase two and if no in LD Graft flicker can be elicited at all by six months, refer to Shoulder Unit Poor Rotator Cuff Control once Transfer seems to be working reasonably well in isolation Inability to activate Deltoid for an Eccentric Deltoid Programme (having checked “Smooth and Weak” Guidelines and Eccentric Deltoid Exercises for ideas) Ensure “snugging” is taking place ie the transfer is working automatically as posterosuperior cuff – if not revert back to ideas in phase three Ensure passive range is gained Isometrics through range Rotation dissociation (cuff control without additional muscle assistance or scapula movement) through range with decreasing levels of support and increasing resistance Slow progression through theraband resistances (e.g. Yellow/white tend to bias cuff and green tend to incorporate deltoid) Ensure there is innervation to Deltoid – i.e. check for history of nerve damage Try activating a static contraction at low level to give patient feedback as to which muscle should be working Ensure the humeral head is located beneath the acromion in passive elevation Try to maximize passive ER at 90 degrees flexion, to ensure the position is encouraging anterior Deltoid activity Ensure that at least 100 degrees passive flexion can be achieved with ease, and more if possible, as in positions lower than 90 degrees, the weight of the limb acting through a longer lever against In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science gravity will increase the work of Deltoid If still concerned, refer to Shoulder Unit Poor Scapular Control Work on scapular setting through range without pec and/or lat overactivity Try closed chain exercises to increase proprioception Consider prone lying to develop control/awareness Poor Core Stability Develop patient appropriate stability programme Secondary ‘frozen’ Maintain passive ROM as able – specifically in shoulder flexion Use manual mobilizations if appropriate Patient exercising too Education on pacing, risks of flare-up scenario vigorously Poor patient compliance Set functional based goals with HEP Return to ADL too soon Reduce activity levels Cervical/thoracic referred Assess and treat pain Altered neurodynamics Assess and treat Many thanks for your help The Shoulder Unit, RNOH References of interest: Iannotti J, et al (2006) ‘Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer for Irreparable Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Tears: Factors Affecting Outcome,’ The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American);88:342-348. - This (albeit small study) suggests that there is a better clinical result when there is synchronous contraction of the transfer present with ER and flexion Aoki M, et al (1996) ‘Transfer of Latissimus Dorsi for Irreparable Rotator-Cuff Tears’ The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Br];78-B:761-6. - Again, it is noted that the patients with the poorer results demonstrated nonsynergistic action of the transferred Latissimus Dorsi and the supraspinatus Gerber (1992) ‘Latissimus Dorsi Transfer for the Treatment of Irreparable Tears of the Rotator Cuff’, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research: 275: 152-60 Holt M, et al ‘GOST3: Guide for Orthopaedic Surgeons and Therapists’, 3rd Ed, Liverpool Upper Limb Unit and South Manchester University Hospitals Trust, Biomet-Merck. - Very useful resource for sample exercises especially glenohumeral rotation control and closed kinetic chain. Contact Biomet-Merck for copies. In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science Kibler W B, et al (2001) 'Shoulder rehabilitation strategies, guidelines and practice', Orthopaedic Clinics of North America, 32, 3, 527-538. McMullen J and Uhl T, (2000) 'A kinetic chain approach for shoulder rehabilitation', Journal of Athletic Training, 35, 3, 329-337. 2008 Tania Douglas Updated – May 2009 (review date May 2011) In association with the UCL Institute of Orthopaedics and Musculoskeletal Science