CASE STUDY Use of a hydrogel dressing for

S12

CASE STUDY

Use of a hydrogel dressing for management of a painful leg ulcer

Ann Moody

Ann Moody is a tissue viability nurse for Morecambe Bay Primary Care Trust, Cumbria Email: Ann.Moody@mbpct.nhs.uk

W ound healing is affected by many variables, which must be assessed before treatment cn commence. These include patient factors (e.g. mental status, age, pain, mobility, nutritional status and comorbidities), wound factors (e.g.peri-wound skin status, vasculitis, cellulitis, wound colour, odour, and incontinence), as well as the macroscopic and microscopic environments (Snyder, 2004). Evaluation of necrosis, infection, nutrition, pressure, perfusion and tissue moisture balance are also paramount (Snyder, 2004).

Because of the multitude of factors that can affect healing progress, wounds cannot be tended to in isolation. The nurse needs to have an understanding of the process of wound healing and have undertaken a full patient assessment before focusing on the patient’s wound. Recognising and managing problems at the wound bed, e.g. necrotic tissue and excess exudate, can result in a better prepared wound bed and optimal healing (Dowsett, 2002).

It is important that any devitalized tissue is removed from a wound as soon as possible. For most patients, the presence of non-viable tissue is distressing as it can produce a noxious odour and frequently an unacceptable discharge. The devitalized tissue provides a suitable culture medium for bacterial growth, and wounds containing necrotic tissue are therefore at risk of becoming clinically infected (Poston, 1996).

Wound exudate is all too often perceived as a clinical management problem. While this can be the case, it should be recognized that exudate does fulfil an important function in the healing process. Gradual acceptance of the

AbstrACt

This case study is of an 82-year-old lady who was widowed and lives alone in a council house. A left lateral leg ulcer had developed over the gaiter area, and the community team were asked to assess in 2004. The main issues were her inability to tolerate compression (even when reduced) because of the pain. Nevertheless, the community nurses had tried very hard with compression, using different compression techniques at different times to try to encourage her to persevere. The nurses felt they were running out of ideas and therefore the tissue viability nurse (TVN) was asked to assess the wound. The TVN recommended ActiFormCool dressing.

This article will examine the background for wound healing, provide the rationale for the recommendation and describe the progress of the patient.

benefits of moist wound healing, combined with the current goals of the ‘ideal’ moist environment, focus attention on the role of exudates (Cutting, 2003). Although wound exudate is necessary for healing, when its production becomes excessive it becomes a problem, contributing to skin maceration and delayed wound healing. Treating the underlying cause of excessive exudate generation and selecting appropriate dressings are the keys to effective management (Watret, 1997).

Chronic wounds

Most chronic wounds have become ‘stuck’ in the late inflammatory phase of wound healing. For the normal repair process to resume, the barrier to healing must be identified and removed through application of the correct techniques (Schultz et al, 2003). This can be distressing and frustrating for patients who may have lived with such a wound for many months or even years. The key to the concept of wound-bed management is to prepare the wound so that modern methods of promoting healing can then be applied (Collier, 2002).

Chronic wounds are characterized by loss of skin or underlying soft tissue and does not progress toward healing with conventional wound care treatment. There are four basic principles of chronic wound care: w Remove debris and cleanse the wound w Provide a moist wound healing environment through the use of proper dressings w Protect the wound from further injury.

w Provide substrates essential to the wound healing process.

The removal of devitalized tissue, particulate matter, or foreign materials from a wound—debridement—is often the first goal of wound care. Debridement can be accomplished surgically (instrument/sharp), chemically, mechanically or by means of autolysis. Each procedure has distinct advantages, disadvantages, indications for use and risks, and a combination of methods will often expedite the process while limiting the chance of complications (Fowler and van Rijswijk,

1995). Underlying the care of chronic wounds is the necessity to assess the wound on an ongoing basis. Changes in wound care must be based on changing wound parameters, and timely, complete and accurate wound assessments must be documented (Frantz and Gardner, 1994).

KEY WOrDs

Leg ulcers

w

Pain

w

Compression

w

Hydrogel

Hydrogels

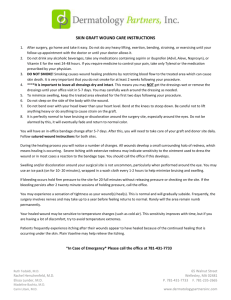

Many different types of wound dressings are available.

It is important that nurses know what sort of dressing

WoundCare, June2006

CASE STUDY

‘Hydrogel dressings can be used on necrotic, sloughy, granulating, and epithelializing wounds (Figure 1) and can be used in infected wounds if the patient is receiving systemic antibiotics and the dressing is changed daily.’

is appropriate for a patient’s highly exuding wound, as using the wrong dressing can lead to repeated dressing changes and soiling of clothes and bedding and will undermine the patient’s faith in care (Anderson, 2002).

Although surgical

(sharp) debridement is the most rapid and effective technique for removing devitalised tissue, topical enzymes, moisture-retentive dressings, biosurgical therapy and vacuum therapy have been used as alternative approaches to wound cleansing and preparation

(Bowler, 2002). However, the simplest and most cost-effective method of removing devitalised tissue is through autolytic debridement with wet dressings such as hydrogels.

On a molecular level, hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers. Depending on the type of hydrogel, they contain varying percentages of water, but do not altogether dissolve in water. Despite their high water content, hydrogels are capable of additionally binding great volumes of liquid because of the presence of hydrophilic residues. Hydrogels swell extensively without changing their gelatinous structure and are available for use as amorphous (without shape) gels and in various types of application systems, e.g. flat sheet hydrogels and non-woven dressings impregnated with amorphous hydrogel solution.

These products consist of hydrophilic homopolymers or copolymers which interact with aqueous solutions, absorbing and retaining significant volumes of fluid. Flat sheet hydrogel dressings have a stable crosslinked macrostructure and therefore retain their physical form as they absorb fluid

(Vernon, 2003). The selected dressing in this case study was a sheet hydrogel (ActiFormCool ® , Activa Healthcare).

Hydrogels, in the form of amorphous gel, have been successfully used for aiding debridement for longer than a decade, their primary role being particularly rehydration of dry necrotic wounds. Hydrogel dressings can be used on necrotic, sloughy, granulating, and epithelializing wounds

( Figure 1 ) and can be used in infected wounds if the patient is receiving systemic antibiotics and the dressing is changed daily (Morgan, 1997). (However, if the infected wound is producing copious amounts of exudate, applying an amorphous hydrogel may lead to maceration of the skin edges).

Hydrogels are therefore of value in a wide spectrum of wounds (Flanagan, 1995). Most hydrogels have a high water content of approximately 70% and it is this factor that successfully promotes rehydration. Hydrogels also have the ability to absorb some fluids from low exuding wounds, However, if used in sloughy and highly exuding wounds, hydrogels can begin to donate fluid to the wound

(Hampton and Collins, 2003) and this can increase the fluid levels in the secondary dressings and may escalate potential for this fluid to macerate the surrounding tissues. Slough is partly rehydrated necrotic tissue and also requires a moist environment if complete debridement is to be achieved.

ActiFormCool

ActiFormCool dressings are two-sided, colourless, transparent hydrogels formed around a supporting blue polyethylene matrix and contain approximately 70% water with the remaining 30% consisting of a swollen acrylic polymer with phenoxyethanol as a preservative. The gel is permeable to water vapour, gases and small protein molecules, but impermeable to bacteria. The cooling element of the dressing provides a moist environment at the surface of the wound and this has been found to reduce pain in painful wounds (Hampton, 2004; Collins and Heron 2005).

ActiFormCool may be placed directly onto the surface of an exudating wound and held in place with tape or a bandage, as appropriate. If additional absorbency is required, an absorbent pad may be placed immediately over the dressing.

The dressing liner must always be left in place unless there is a large volume of exudate. Painful wounds (where the pain is actually in the wound, not in the surrounding tissues) also benefit from a moist environment (Flanagan, 1997) as the moisture ‘bathes’ nerve endings and can reduce pain.

The ActiFormCool hydrogel sheet moistens the wound and slightly and temporarily drops the temperature of the wound (data on file, Activa Healthcare) thereby soothing painful tissues. The temperature then climbs to an optimum condition to promote wound healing.

ActiFormCool may be used as a wound contact layer, providing cooling and soothing, as well as exudate absorption and retention and is primarily indicated for burns, scalds, radiation therapy damage and epidermal damage.

ActiFormCool should not be used as a covering for deep narrow cavities or sinuses.

ActiFormCool may be placed directly onto the surface of an exudating wound and held in place with tape or a bandage, as appropriate. If additional absorbency is required, an absorbent pad may be placed immediately over the dressing.

As with all wounds, frequent monitoring is required and the dressing should be changed as often as the condition of the wound dictates (Collins and Heron, 2005) or when it becomes cloudy or opaque owing to the absorption of wound exudate. In the treatment of an infected wound, it may be necessary to change the dressing more frequently.

the case study

The patient, an 82-year-old lady, had a venous leg ulcer of 5 months’ duration on the left lateral gaiter area ( Figure 1 ).

The ulcer was shallow, diffuse and exuding high amounts of fluid, presenting initially with two management problems: that of a sloughy wound bed, and maceration to the peri-ulcer skin. A key objective of the consequent wound management plan would be to remove the slough and promote the growth of granulation tissue (Gray et al, 2005) while concurrently managing the exudate. Slough formation is common during the inflammatory stage and occurs when a collection of dead cellular debris adheres to the wound surface, creating a fibrous cover across the bed of

S14 WoundCare, June2006

CASE STUDY

Figure 1. July 2004. The ulcer had been unhealing for 5 months. It is macerated and painful.

the wound. Slough must first be removed from the wound bed in order that an optimal environment may be achieved to promote the formation of granulation tissue.

Maceration occurs when excessive amounts of fluid remain in constant contact with the skin. Wound exudate, while an essential component of the local wound healing environment, can provide this excessive fluid. The enzymatic component of the exudate can lead to skin damage and even an increase in size of ulcer.

The ulcer had previously been managed by the district nurses who initially tried a 4-layer bandaging compression system. Despite the use of this compression, the ulcer continued to produce large amounts of exudate and daily visits by the nurses were required in order to manage it. As time passed, the patients ability to tolerate the compression produced by the 4-layer system declined. The compression was therefore changed over time to 3-layer, then to short stretch bandages. Several factors contributed to the patient’s changing response to compression, including pain caused by the ulcer and despondency that the ulcer was not healing.

The management of this patient raised a number of concerns among the district nurses, and the team eventually concluded that with respect to this particular patient, they were running out of ideas, although the problem still remained. This prompted intervention by the tissue viability nurse specialist (TVN).

The initial TVN assessment was made in July 2004

( Figure 1 ). Although the lady had an independent rubor, with capillary refill when dependent, the toes blanched when elevated, suggesting there may be an underlying element of arterial aetiology. However, there was no resting or night pain reported. The limb was generally oedematous and Doppler assessment gave an ABPI of 1.02. Taken on balance it was decided that it was safe to compress. The ulcers were wet, but the skin on the feet was dry.

Holistic assessment and a care plan tailored to reflect a patient’s individual needs are an essential component of leg ulcer management. Local documentation and guidelines developed by the TVN take the assessor through a logical series of questions which considers many aspects of the patient as a whole person: staring with height, weight and blood pressure, the assessment proceeds through past medical history (including details of pregnancies), current medication and any known allergies, social details (e.g. support networks, mobility, where they sleep (e.g. chair/bed) etc) and progresses to undertake a general health assessment, before examining the leg, skin and finally the ulcer. Very detailed note is taken of the ulcer history (and any previous ulcer history) position of the ulcer, surrounding skin condition, wound edges, depth, exudate and level of joint mobility and pain. Only then is the Doppler assessment used to support the clinical presentation of the ulcer, and a diagnosis made. This holistic and systematic approach not only supports a reliable diagnosis but has also been shown to help achieve concordance: working with the patient to address their main identified problems helps to formulate a care plan which is more likely to be acceptable to the patient and therefore adhered to.

In the case of this patient, the main issues were pain, and quality of life relating to the amounts of exudate. Leg ulcers, in particular, have been shown to have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life, with experience of pain being the most overwhelming feature. In addition patients have found the effects of coping with leakage and odour from wet dressings to be particularly distressing and at times unbearable, often leading to social isolation (Charles,

1995; Walsh, 1995; Neil and Munjas, 2000; Douglas, 2001;

Rich and Mclachlan, 2003).

Following the initial assessment in July 2004, a hydofibre dressing was applied to the ulcer bed to act as a soothing wound contact layer. It was also capable of desloughing, absorbing exudate and providing an optimal environment for granulation to take place. This was combined with a full compression bandage system which should aid venous return, reduce oedema and further help to control exudate levels.

Unfortunately during the following 3 months the patient was unable to tolerate the compression because of discomfort at the ulcer bed, and between July and

October the wound began to obviously deteriorate, the ulcer extending in size and maceration developing to the peri-ulcer skin ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. October 2004. Maceration and an increased ulcer size indicate deterioration.

S16 WoundCare, June2006

CASE STUDY

This was not an easy case but it was certainly a successful one from this perspective.

Conclusion

This case study shows that there are simple solutions to problems within wound care, but that requires careful thought and assessment of the individual patient. In this instance,

ActiFormCool was the ideal dressing and led to concordance of the patient and healing of the wound. BJCN

Figure 3. May 2005. The wound is all but healed at this point.

A decision was made by the TVN to change the primary wound contact dressing to ActiFormCool, because of its properties of soothing pain. ActiFormCool has a high absorption capacity (Hampton, 2004) and can be cut to the shape of the wound if required. This ensures that the peri-wound area does not become macerated.

ActiFormCool also helps with pain reduction (Collins and Heron 2005; Hampton, 2004) and when pain is reduced quality of life is improved (Hampton and Collins,

2003). ActiformCool’s ability to donate moisture to a wound would also provide an agent to deslough the wound by autolysis.

ActiFormCool suited the patient – pain was reduced, and exudate levels managed, and she became able to tolerate therapeutic compression. By the next TVN review in February 2005 dressing changes were reduced from daily to every third day. The following TVN review was made in May 2005. The community nurse visits had now been reduced to twice weekly and the wound was almost healed.

Since the patient was experiencing repeated minor trauma injuries to her leg when inexperienced carers applied the Class 2 compression hose, a decision was made by the

TVN to modify the treatment and it was changed to using two liners from the Activa 2-piece kit: since the white liner is extremely easy to put on trauma was avoided. However, as the liner only applies 10mmHg pressure, a second liner was applied over the first giving a total pressure of approximately 20mmHg. This approach enabled compression therapy to continue where otherwise it may have had to be abandoned. This is not recommended practice for compression, but it was the only method that the patient would tolerate. Figure 3 (dating from May 2005)shows the skin to be clear of maceration and the ulcer all but healed.

The wrinkles show that although the compression was not the recommended method, it worked for this lady and reduced the oedema, which led to the natural wrinkling of the compressed tissues.

Anderson I (2002) Practical issues in the management of highly exuding wounds. Prof Nurse 18 (3): 145–8

Bowler PG (2002) Wound pathophysiology, infection and therapeutic options.

Ann Med 34 (6): 419–27

Charles H (1995) The impact of leg ulcers on patients’ quality of life. Prof

Nurse 10 (9): 571–4

Collier M (2002) Wound-bed management: key principles for practice. Prof

Nurse 18 (4): 221–5

Collins J, Heron A (2005) Stages of wound healing: applications in practice

– Abstract. Wounds UK 1 (2) [AQ10 Pages?]

Cutting KF (2003)Wound exudate: composition and functions. Br J Community

Nurs 8 (9 Suppl): 4–9

Douglas V (2001) Living with a chronic leg ulcer: an insight into patient’ experiences and feelings. J Wound Care 10 (9): 355–60

Dowsett C (2002) The role of the nurse in wound bed preparation. Nurs Stand

16 (44): 69–72

Flanagan M (1995) The efficacy of a hydrogel in the treatment of non-viable tissue. J Wound Care 4 (6): 264–7

Flanagan M (1997) Wound Management . Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Fowler E, van Rijswijk L (1995) Using wound debridement to help achieve the goals of care. Ostomy Wound Manage 41 (7A Suppl): 23S-35S; discussion 36S

Frantz RA, Gardner S (1994) Elderly skin care: principles of chronic wound care. J Gerontol Nurs 20 (9): 35–44, 74–6

Gray DG, White R, Cooper PJ, Kingsley A (2005) Understanding Applied

Wound Management. Wounds UK 1 (1): 62-8

Hampton S, Collins F (2003) Tissue Viability . Whurr, London

Neil JA, Munjas BA (2000) Living with a chronic wound: the voices of sufferers.

Ostomy Wound Manage 6 (5): 28–38

Poston J (1996) Sharp debridement of devitalized tissue: the nurse’s role. Br J

Nurs 5 (11): 655-6, 65–62

Pudner R (1998) Hydrogels. Practice Nursing 9 (16): 201

Rich A, McLachlan L (2003) How living with a leg ulcer affects people’s life: a nurse led study. J Wound Care 12 (2): 51–4

Russell L (2000) Understanding physiology of wound healing and how dressings help. Br J Nurs 9 (1):10–16

Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V et al (2003) Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 11 (Suppl

1):S1–S28

Snyder R (2004) Proteases in wound healing: understanding how these chemical mediators work represents a paradigm shift in wound care. Podiatry

Management (www.podiatrym.com - subscription required)

Vernon T (2000) Intrasite Gel and Intrasite Conformable: the hydrogel range. Br

J Community Nurs 5 (10): 511

Walshe C (1995) Living with a venous ulcer: a descriptive study of patients’ experience. J Adv Nurs 22 (6): 1092–100 Watret L (1997) Know how … management of wound exudate. Nurs Times 93 (30): 38-9

KEY POints

w Holistic assessment is essential to identify and address all the factors affecting the formation and healing of a wound.

w Wounds cannot always be treated in the ideal way.

w Treatment should aim to achieve the best fit between the clinical priorities and the patient’s needs, which may not be the same.

Regular reassessment is needed to monitor the wound. Changes in the wound may require changes to the treatment regime.

w In this case, ActiFormCool and reduced compression were able to address the patient’s needs for exudate control and comfort

WoundCare, June2006

S17