Part II The Golden Age - The Center in Jerusalem

advertisement

II

Part

The Golden Age - The Center in Jerusalem,

Tenth and Eleventh Centuries

"Mourners a/Zion" and the "Congregation a/the Roses"

One of the strands leading to Karaism were apparently the Jerusalem "Avelei

Zion" (Mourners of Zion)!. Jews devoted to mourning the destruction of the

Temple and praying for the redemption of Zion are mentioned already in late

Roman times2• They appear again after the Arab conquest and are mentioned

there throughout most of the "Umayyad period (660-750). The term "Avelei

Zion" is mentioned fIrst in_the fIrst half of the ninth century3. ~

Their customs, such as a life of strict~poverty, abstaining-from the

consumption of meat and wine, and of fasting, were influenced by customs

which some of the early_Karaites--imported from Persia. The Karaite

settleiiient in ~s~tarted

in the ninth century (A. Paul believes that

around 85()4). Do we h,ave to regard all Avelei Zion after that date as

Karaites, or did Rabbanite Mourners exist in Jerusalem side by side with the

Karaite ones? Scholars are divided on this questions. But in due time

"mourning" became synonymous with Karaite allegiances. Increasin~ly the

appelation of Mourners dis3ppp.Med however, t<!l he rep13ced hy "AdM

n •..•

f t1l~ :R\?fJ8fJ"), '.'.'hkb "',,,, <>pplif'cI to

Hashushanim" (the "Conwgllti •..•

Karaites only6 LS~H On

Their settlement in Jerusalem was facilitated by political developments.

Cracks appeared in the monolithic structure of the Khalifate. Egypt broke

away, under the Tulunids, and captured Palestine in 878. Thus Jerusalem

became dependant on nearby Fustat (next to present day Cairo), instead of

far away Baghdad. Some of the Karaites enjoyed considerable influence at

the court of Fustat and later of Cairo, and were thus able to be of very real

help to their brethren in Jerusalem, especially in their conflicts with the

Rabbanites. The Gaon Ben Meir complained in a letter written in 321, about \A.l~

how the Rabbanites of Jerusalem had been persecuted by the local Karaites. ti.o.*L

••......

-

29

Thus quite an exceptional situation came to be, with the Karaites as the

stronger and more aggressive side7.

Some of the Karaites sent letters to members of the sect living in the

Diaspora,inviting them to come to Jerusalem and join them there in a life of

poverty and prayer.Thus, they hoped, to accelerate the coming of the

Messiah. Belief in the imminent advent of the Messiah was widespread, as

shown by various Karaite texts. In some cases specific years or months were

mentioned as the time in which his coming could be expected. When nothing

happened at the stipulated date, various excuses and explanations were put

forward, but the basic belief endured8.

The holiness of Jerusalem was accepted by all branches of Judaism, but

the active propagation of settling there became a specifically Karaite trait.

Several well known Karaite scholars, such as Daniul nl-Kumisi and saW ben

Mazliah toured the neighbouring countries and wrote letters in order to

promote the settlement of Jerusalem.

The quarter settled by the Karaites in JCIIINUlulTI

was outside the city wall,

on the (eastern) hill, where the original city of the Jebusites and King David

had stood. It was called Haret al-Mu::;hul'ukah(the quarter of the easterners)

because the Karaites who settled there Cllu10 from such eastern countries as

Persia. They themselves called it "~~Iu Eloph", alter Joshua 18:289. Their

Rabbanite opponents called them accordingly "The sect of the Zelah"" or,

from the same Hebrew root, "The IlllllO Noet"10. No archeological remains

have been found of thjs period in l'hi~ mllt·h "'Y"~"M"r1 part of Jerusalem, but

we have to imagine the Ka:raitc Q)IHl'ltW III IHlvehe~n a poor locality of narrow

•••..

alleys because of the Bfo-stylc of its lllhlll)l!'nnts..

Still, the existance of un hnportllllt Yl.lNhivah(academy) is reported from

this quarter. It was located in diU "coul'tyurd" (meaning the group of houses

surrounding a courtyard) of Joseph ben Bakhtawi, one of the richest and

most influential members of the Karalte comnunity, around 1000, and was

therefore named the Bakhtawi Academy. Tho Bakhtawi "courtyard" seems to

have served also as the Karaite communal center ("maglis") of JerusalemJl•

Students were sent even from abroad to study there. In the 1030's studied

there, for instance, Tobias ben Moses, from Byzantium. Some of the students

decided to settle in Jerusalem for good, but Tobias was, in the end, disgusted

with the discipline imposed by the Karaite Nasi, and by his mishandling of

funds - and returned home. Another such student, about a generation later,

was Jacob ben Simon, who translated into Hebrew one of his mentor's,

Jeshua ben Judah's, Arabic-language treatises on the law of incest. He, too,

returned to Byzantium. The academy declined after one of the nesiim had left

30

around 1060 for Fustat, and might have closed down round completely after

the Seljuk conquest of 107112•

It seems probable that there were at least as many Rabbanites as Karaites

in Jerusalem, as the city served in the tenth and eleventh centuries as the seat

of the important Rabbanite academy called "Yeshivat Bretz-Israel" (which ~

previously had been located for several centuries in Tiberias, and later was to

move to Tyre). saW ben Mazliah mentions in the tenth century sixty Karaite

sages in Jerusalem. This might refer to the number of active male Karaites in

the city, which would indicate a total Karaite population there of some 250

soulsl3. The Karaites stressed that they were in Jerusalem poorer than the

Rabbanites, and had fewer childrenl4. Yet a document from the Genizah

from 1040 shows Tobias ben Moses, when living in Jerusalem, to have been

a wealthy man, who was in charge of the Fatimid landed estates in all of

Palestinel5. Even more surprising: the Karaite Abu Sa'ad Itzhak: ben Aaron

ben Ali (or, in Arabic, Ishak: ben Kalafben 'Alun) served in 1060 as governor

of Jerusalem - a nearly unprecedented honour for a non-Moslem. He was

however unlucky: during his term of office the lightening installation of the

Dome of the Rock collapsed. This was regarded as a very bad omen and he

was speedily removed. Later he lived in Ramlel6.

The organization of the Karaite community is hinted at by Levi ben

Japheth Abu Sa'id, who mentions the following appellations of its leaders:

"Nasi':, "Adon" and "Melamed". The latter which means "teacher", was

subdivided into an instructor who taught "Tora and matters of the next

,world" and one who imparts "matters of this world" and handicraft. Another

Karaite scholar, Abraham ibn David, mentions also a further appellation,

"Sheikh". This Arabic term means much the same as the Hebrew "Adon" - a

communal leader. "Nasi" was reserved for the head of the community, a

descendant of Anan.

Anan is supposed to have built the old Karaite synagogue in Jerusalem.

This is clearly incorrect, not only because there is no corrobative evidence

for Anan's ever having visited Jerusalem, but because the architectural style

of the building indicates, according to J. Pinkerfeld, rather the eleventh or

twelfth than the eighth centuries. Ben Shamai suggests that it might have

been set up by Anan II ben David, one of the Ananite leaders, who had

become a Karaite in Jerusalem in the eleventh centuryl7. Its present state is

the result of two rebuildings in the nineteenth century. The original prayer

room was somewhat largerl8. M. Gil does not believe that the synagogue was

built before the crusadesl9, but that would leave us with a thorny question:

when was it built? Still, Gil is backed up by the fact that it stands in the

31

Jewish

quarter

on the

chapter

Quarter of the Old City (within the city walls), while the Karaite

of the tenth and eleventh centuries was located outside the city walls,

"Eastern Hill". We shall come back to this problem in the second

of Part N.

The various Karaite sources show that most of the members of the sect in

Jerusalem had initially come there from Persia. A later French document tells

about a ~banite

couple w:ho~ved

in J~sale~

frofu Spainfand

decided there to become Karaites and to settle in the Karaite quarter. But

when, after two years, they decided to return to the Rabbanite fold, they~re

accepted only after great difficulties20. Other sources mention repeatedly

some~mixed marriages between

Karaites and Rabbanites21.•.

...........--.

The Karaites in Jerusalem were dependant for some pwposes on the

Rabbanites and had, apparently, to pay their taxes to the Moslem authorities

by means of the Rabbanites as intermediaries. To thank them for their help

they had to close their shops not only on their own festivals, but also on the

Rabbanite ones. Quite some bad blood was caused by the different customs

of both sects. The Karaites were allowed, for instance, to eat meat and milk

products at the same meal, which has always been very strictly forbidden to

the Rabbanites. The latter used therefore each year on the day of Hoshana

Rabba (the seventh day of the Feast of Tabernacles), to have a ceremonial

gathering on the Mount of Olives, and to read then out a ban against the

Karaites, mainly because of their dietary laws.

the ear 1024 the Karaites succeeded, with the help of their influential

di ionists in Fustat to 0 tam l'om t 1e al1llU Khalif a _ r ,.; , ...

~s ban and also 0 the Rabbanite visits to any Karaite places of worshi~ and

of the Rabbanite polemics against them. Not all the Rabbanites were

prepared to accept this ruling, and two sons of a previous Gaon (head of the

Jerusalem Academy) read out the bim, in spite of the prohibition. The

authorities had them arrested and they were deported to Damascus (1030).

However they were later released and it is not clear whether the ban was or

was not read out in later years22.

In the second quarter of the eleventh century the relations between

Karaites and Rabbanites in Jerusalem improved markedly. When Ramie was

badly damaged in a Beduin raid in 1025, the Fatimid authorities levied a

special tax of 6000 dinars on the Jews of Jerusalem, in order to help the

victims, half of it was contributed by the Rabbanite community and half by

the Karaites. This shows, first of all, a new spirit of cooperation and further it

can be taken, perhaps, as an indication that both communities were of about

equal size at that time23.

-

32

----

A further indication of cooperation can be seen in the fact that in 1028 the

h~n JehuWlb ~erved in ~

~ Sl)aliah T_~ibur(leader in

"prayer) both of the Rabbanites and thy l>araite~ ll~ hp. rp.l'mmt" h;~~lf y:ilik

(,5omehumour24.

The period of the main flowering of the Jerusalem Center was in the tenth

and eleventh centuries. Some of the most important Karaite scholars were

active there, writiI;g mostly in Arabic (but usually with Hebrew letters) and

only rarely in Hebrew. H.H. Ben Sasson characterizes them as individualists

of a rationalistic turn of mind, who were united by their similar attitude to the

Scriptures, to Karaite history and to direct communion with God27. Further

they had in conmon that tilev did not believe that recompense for good deeds ~

i!1 this world should be looked for in the next world. They did believe that the

Torah indicates clearly that reward and punishment are only possible as long

as humans are still alive, and body and soul are conjoined, as this is the way

God creates them; while in the next world the soul survives without the

body28.

They believed that a catastrophic cataclysm had occured in history: the

destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Before this catastrophy the

recompense in this world was commensurate with the good deeds performed

by man. But afterwards this was no longer so, as God ceased to be in direct

contact with His creation. Therefore they had chosen poverty as their way of

life, as no other reward could any longer be looked for. Still, they call all

believers to come to Jerusalem, as only there is any hope of reestablishing

contact with God and of overcoming His anger towards His creation29.

With the capture of Jerusalem by the Seljuks in 1071 the real flowering of

the Karaite "Congregation of Roses" seems to have come to its end. But the

final stroke was delivered by the crusaders in 1099, as we shall show in the

last chapter of Part II.

.G~\WL.sW,Q.mo.U

The Karaite Social Fabric

Karaite ideology stressed in these centuries the importance of poverty. There

can be but little doubt that in their quarter outside of the city walls, with its

narrow alleys and small houses, the general standard of living was a low one.

But the picture painted by the Marxist historian R. Mahler of "downtrodden

Jewish masses" for whom Karaism was a movement of messianic and social

liberation1, is surely an overstatement. His modern terminology tends to

confuse a medieval situation to which it does not apply.

33

)

ll.ll. Ben Sasson has criticized Mahler's concept on several accounts2

* The severe legal code, especially of Benjamin Nahawendi, reflects

a

very different society from that imagined by Mahler. It shows an appreciation of property and the men of property can expect full legal backing and

protection.

* l(araite societr inclllned al~o ~eat ml"rrh<ant" :InrI l"ven cle1l1en::in Sl~ya....

(such as the Tustar clan of Egypt. f?r instance). beside artisans. peddlers and

the poor.

*~i1e

MaJ11prp;n0ri7.~d the hil!h taxes collected bv the sendlinJ:!jSof the

titb~s

»abYlonian exilarch, Ben Sasson pOints to the relativelv hi~htaXjs

.coll\'(Cteq late{ yi~orQUIlJv - even frQrn womvn - bv QJ~ Kar~i: le.l!ders~ •

* The lender of money is given precedence before orphans by Karaite law,

indicating a society with a highly developed sense of the value of property.

Borrowers who cannot pay may even be sold as slaves.

M. Gil has pointed out that some of the teachings of al-Kumisi and his

pupils, such as the ideal of poverty or asceticism and self-mortification,

do

indeed give the impression of a new social code. He stresses however that it

was held, at best, by a small group, nearly all of whom lived in Jerusalem.

Sahl ben Mazliah reports that some of the newcomers to Jerusalem lived

;9.

under difficult economic conditions. Still, it appears that he is speaking

mainly of previous members of the wealthy merchant class3.

Even in Jerusalem dwelled the wealthy Bakhtawi family, and a member of

the rich Tustar family was an active scholar there late in the eleventh century.

Goitein points out that the Genizah documents indicate that the Karaites

were generally richer than the Rabbanites, especially in Egypt. Two marriage

contracts from Jerusalem show that the newlyweds came from rich families.

In the previous chapter we have had occasion to mention Karaites who

occupied high office in Jerusalem. But other Karaites mentioned in this

period were sellers of cheese, or weavers, or lived from alms received from

their previous home towns4.

Daniel hen Moses al-Kumisi

He was the earliest of the important Persian Karaites in Jerusalem.Al-Kumisi

was born in Damghan, in the province of Kumis, in northern Persia.

Ben Shamai believes that actually he should be classifIed as an Ananite in

his early life, and only after arriving in Jerusalem he became a Karaite. The

Arab 1l1athematician al-Birulli (975-1048) reports that the members of one of

34

the Jewish sects are called the Ananites. He claims that the split occured a

hundred years before his time, which would place it arround the year 900 the time when al-Kumisi was active in Jerusalem. Ben Shamai regards this as

an epochal event in Karaite history, as from al-Kumisi onward the Karaite

ideology became dominant in the general Jewish sectarian religious ferment

of that periodl.

M. Gil sugges~ that al-Kumisi has to be understood against the background of the rising Isma'ili movement in his native Persia. Its preachers

were called duai, which can be translated into Hebrew as "hakore", "the

caller", and hence, perhaps, the source of the term "Karaite". Daniel alKumisi was such a preacher, or "caller". Some of his commentary to Leviticus shows Isma'ili influence, mirroring its teachings about the "dahir" and

the "batin" - the revealed and the concealed - in the Koran2.

AI-Kumisi mentions Persian political events, which took place in the third

quarter of the ninth century. He seems to have moved to Jerusalem around

8803•

He is the main follower of al-Nahawendi in the integration and unification

of the Karaite movement. He had, at least in his later life, few illusions about

Anan's actual importance in the formation of Karaism, dissented from some

of his halakhic principles, and after calling him "first among the sages" called

him later, after his conversion to Karaism, "fIrst among the fools". Probably

as a result, his name was excluded from the later Karaite memorial prayer, as

Anan had been accepted by then as the sect's founder.

Nor was he any less critical about Nahawendi.

He opposed his

11lh"IJ)fotal'ionof the law, and taught a much stricter version. He believed that

tho IIIWHof the Torah should be followed as originally formulated. He opptlNlld Nflhnwondi's method of Biblical exegesis and called for strict

IIdlu.)I'ulI(;i)to tho literal sense of Scripture. He did not accept Nahawendi's

lukqlJ'ctatioll that I'malakhim" are angels and preferred to regard them as

1111

LlI I'll I fOfCOHumployed by God.

's wide ran e of disa reement between

thu l'lJfl;UlTlONtimportant founders of Karaism shows from how . erent

Nognlcllt'~llOVl.lmcnt

was originallx fused together, and on how wide a

I'!'O III ngfcblllClllN hlld 1'0 he hammered out.

Kir:ki/'lUul fOllllll'kod about al-Kumisi's ways of thought and work: "He

would aCCl.lpllillY l.:ouc1usion arrived at by reasoning ... and would acknowh'd~() dUII1/J,l'HW1WIlUVUf

they occured in regard to opinions he had expressed

II hiN WllllllI'.M". Al-Kumlili himself stated "Those who come later will find

Ihfl 1I11I'h",Nhowlllg 1\ ¥(.)ry modem, empirical attitude towards the nature of

llllowh·dgo.

Y01 hll oppOIlt;d the study of philosophy among Karaites.

35

In his biblical exegesis al-Kumisi tries to keep to the simple meaning of

the text, in a rationalistic manner. His most complete surviving works are

commentaries on the Minor Prophets and on Daniel.

His most bitter criticizm was reserved for his Rabbanite adversaries,

whom he blamed for the prolongation of the Diaspora, because of their

arrogance, pursuit of worldly pleasures and wealth, their exploitation of the

masses of the people and, mainly, their erronous reliance on Oral Law.

AI-Kumisi seems to have been the real originator of the new Jerusalemcentric orientation of Karaism, which he might have regarded as a

counterbalance to the previously dominant Rabbanite center of Babylonia.

He appears to have been the real founder of the "Congregation of the

Roses" and was apparently the author of the official program of the

"Mourners of Zion". He initiated the energetic Karaite propaganda for

settling in Jerusalem and demanded, from Karaites living elsewhere, to

supply the funds needed to enable their coreligionists in Jerusalem to

dedicate their lives to prayer, to active mourning and to supplication for

redemption. Some of the epistles from Jerusalem called from now on for

speedy immigration to the Holy Land, while the "Rich of the Diaspora" were

bitterly denounced for hanging back4•

His appellation for the rabbis and hakhamim of the Karaite community in

Jerusalem seems to have been "Maskil", as used in his commentary on

Daniel. J. Mann has translated it as "wise man"5, 1. Nemoy as 'Jnan of

1!!lderstanding"6, N. Wieder as "those who make wise", meaning teachers,

guides or enlighteners7 and A. Paul as "sage"8.

M. Gil regards al-Kumisi as the real founder (or unifier) of Karaism, who

bestowed on it its three main characteristics

* Comolete dissociation from Rabbinic teachin~s

* Return to the Land of Israel

* The use of self mortification and self torture and also the active habits of

mourning9•

The Karaite scholars of Jerusalem

This is the Golden Age of Karaism. Even in Rabbinic circles respect was

expressed for the quality of learning to be found among the Karaite

"Teachers of Jerusalem" and "Exegetes of Jerusalem"!.

* 0bu Suri Sahl ben Mazliah ha Kohen lived in the tenth century. He

wrote a commentary on the Bible called "Mishneh Torah" and an Arabic

36

language Book of Precepts, but with a Hebrew language introduction, which

includes interesting material on the Karaite cornnunity of Jerusalem. Further

he wrote a book of Hebrew grarnmer and a Hebrew tract, named "Reproach

from the Diaspora", addressed to one of Saadia Gaon's pupils.

He was an energetic Karaite missionary, who travelled to Egypt and Iraq.

He and his fellow propagandists were so successful that he boasted of the

fact that several Rabbanites in Jerusalem and RamIe had adopted major

Karaite practices: "There are many of them who eat no meat of sheep and

cattle in Jerusalem and keep their mouths clean of every unclean food ... And

they do not touch the dead and do not become defiled by any of the

impurities ... They also refrain from marrying a daughter of one's mother and

a daughter of one's sister and a daughter of the wife of one's father and they

refrain from all the prohibited incestuous unions which the Karaite scholars

.., have proclaimed as forbidden ... They celebrate the festivals for two days

... There are some among them whose eyes God has ultimately enlightened

so that they have forsaken the calculation of leap-years"2.

He was no less vigorous in his propaganda for the return to Zion, and

reports at some length about the struggles between the Karaite leadership of

Jerusalem and the Rabbanite leadership of the "Land of Shine'ar "

(Babylonia)3. He stressed that in coming to Jerusalem the newcomers were

fulfilling a Divine command. Quoting Jeremiah 3:14 he calls for "One from a

£ity and two from a family, old' and young" to ioin the ranks of the

'.:Mourners of Zion"4.

The modern Karaite settlement _Mazlial1_in Israel (founded in 1950) is

named after him5.

*"Salmon ben Jeroham, in the tenth century, was one of the main Karaite

polemicists against Saadia Gaon. His "Milhamot Adonai" (Book of the Wars

Qf the Lord), written in Hebrew, is a rhymed attack on Saadia and on

Rabbanites in general. Ankori calls him an "ascetic zealot" 6. Abusive

language was the norm of the age, but Salmon outdid in this field all his

contemporaries. He wrote also some cornnentaries on the Scriptures. In his

view s,ecular studies were to be avoided, as ungodly. He also opposed the

study of philosophy.

He had decided political opinions. Living in the time of the progressive

disintegration of the Abbasid Caliphate, he had few illusions as to the real

nature of Islamic rule. He called it "son of a slave girl" and "man of deceit"7.

Yet he regarded the possibility that Christendom would reconquer Palestine

as an even worse alternative.

37

He seems well acquainted in his writings with the topography of Jerusalem

and the Dead Sea, yet his last years he seems to have spent in Aleppo and his

grave there was still venerated in the fifteenth century8.

* David ben Boaz (Abu Sa'id) was a descendant of Anan and lived in the

tenth century. He was the titular head (Nasi) of the Karaites in Jerusalem. Yet

he had some ties to Saadia Gaon, which is perhaps not swprising in a man

with Ananite roots. He wrote in Arabic. From his translation of the

Pentateuch some portions on Exodus, Leviticus and Deuteronomy have

survived as MSS in Leningrad and in the British Museum. He added to his

translations also a commentary and prepared another one on Ecclesiastes. In

these commentaries David opposed in a restrained manner some of Saadia's

opinions, using in his arguments sometimes quotations from the Talmud.

Further, he added grammatical glosses. His comnentary on Leviticus was

later used by Tobias ben Moses as an essential component of his "Otzar

Nehmad". But otherwise David's Arabic work was not translated into

Hebrew and, as a result, did not exert much influence on the later, nonArabic speaking, scholars of the Byzantine Period.

* Japheth ben AU ha-Levi (Abu AU aI-Hassan ibn Ali), was born in Basra

(hence his Arabic appellation "al-Basri"), in the middle of the tenth century

and was still alive in 985. In his youth he came to Jerusalem and in his

writings shows some knowledge of the topography of the city and of the

Holy Land.

He prepared a monumental literal translation of the Bible into Arabic and

wrote, also in Arabic, biblical commentaries, which won him considerable

renown. L. Nemoy has called him "the foremost Karaite commentator on the

Bible during the golden age of Karaite literature"9. Parts of the commentaries

were later translated into Hebrew and were used in later centuries by the

Karaites of Byzantium. Included therein can be found sharp polemics against

Rabbanites in general and Saadia Gaon specifically, but also against

Christianity and Islam. He is also critical of Anan and Nahawendi. His Book

of Precepts has not survived.

He admired the resurgent power of Byzantium under the Macedonian

dynasty and wrote about it "The iron represents the Romans and the clay the

Arabs ... But the kingdom of the Romans remained, as is witnessed in our

own day. Now, the kingdom of the Arabs is compared to clay, because they

have neither power nor force like the Romans"10.

He attacked the creed of Tiflisism, saying in conclusion "God shall cancel

these creeds and bring shame on (their adherents)"11,partly, perhaps, because

38

they appeared not to believe in resurrection, while he was convinced of the

imminence of the coming of the Messiah.

He called on the Karaites of the Diaspora, to come and settle in Jerusalem:

"Ye Mourners of Zion, remember your Mother from afar; sit not in gladness

in the company of the playful: Your Holy House is in the hands of strangers,

yet you are far away. The enemies of God are within it, yet you are

unmindful. Strive ye to appear before Him!"12

He is a typical representative of the intelligent, politically aware, critically

inclined Karaite scholar of that age.

* His son Abu Sa'id Levi ben Japheth lived in the time of the widespread

Carmathian uprisings in Palestine, to which he aludes in his "A commentary

on the Book of Daniel"13. He wrote in 1006/7 in Arabic a book on religious

law "Sefer Mitsvoth", later translated into Hebrew. His rulings are very strict.

He is an important source for the controversies between Karaites and

Rabbanites, and those between the scholars of Jerusalem and of Iraq. His

main importance was in his influence on the early Karaite halakha. He

stressed that Karaite legislation can only be derived "from Scripture, and

from deduction by analogy and from seeking for the truth"14.

As against the uncompromising stand of al-Kurnisi and other early

Karaites on the necessity to settle in the Land of Israel, Levi's positiom was

more ·fleXible. The Karaites living there could indeed follow the growth of

the new crop, in order to fix the New Year accurately, but it was admitted

now that most Karaites had to stay in the Diaspora and had to resign

themselves to logical deduction ("hakrabah" or "hagbarah").

This must not be allowed to affect, however, their basically Jerusalemcentric orientation. While this softening of their stand came too late to

remedy the rift with the Karaites of Babylonia, as shown by Levi's

disputations with their scholars, it did come in time to ensure better relations

with other Karaite centers, and especially the rising center of Byzantium.

Hence, perhaps, the later popularity of Levi's writings there15.

* Joseph ben Noah founded, around the turn of the rnillenium, the Karaite

Bakhtawi Academy, of seventy scholars in Jerusalem (possibly to conform

with the number of members of the Sanhedrion). His disciples, such as

Joseph ben Abraham ha-Roeh and Abu al-Faraj Harun, have carved out for

this academy a permanent place in Karaite cultural history. He was reported

to have rejected deduction by analogy, one of the basic tenets of Karaite

doctrine, put none of hi!'; worh have survived-.iwhich reportedly included

both a grammar and a commentary on the Pentateuch). He is regarded by Z.

Ankori as a worthy representative of what he calls the "Later Golden Age",

,

39

which is more mature in its literaty output than its predececessor and

"constitutes a lasting and positive contribution to Jewish learning of all

times"16.

I

I

,

* Abu al-Faraj Harun, in the :f1rsthalf of the eleventh century (he was still

alive in 1048), was a biblical exegete, lexicographer and, especially, a well

known grammarian (he was called 'the Grammarian of Jerusalem'). He was

the fIrst to study the Aramaic language of the Scriptures and its grammar,

and to compare it to Hebrew. He wrote several books, which have survived

mostly only as manuscripts - some of them in Leningrad. His major work

was "al-Mustamil ali al-Ussul wa-al-Fussul fi al-lughah al-'Ubraniah" (The

encompassing book of roots and derivatives in the Hebrew language), which

he completed in 1026. He was a friend of Joseph al-Basir, and among his

pupils were, apparently, Tobias ben Moses and Jeshua ben Judah. His work

was well known among the Jewish scholars of Spain: Abraham Ibn Ezra,

unaware of his sectarian identity, placed him second only to Saadia Gaon17.

* Jeshua ben Judah (Abu Furkan ben Assad al-Faraj) was active in

Jerusalem around 1050 (but lived still in 1065). He was one of the leaders of

the community and is regarded as the last important Karaite scholar of

Jerusalem of the Golden Age. He is the first Karaite.man of letters who had

the full text of Anan's "Book of Precepts" in its original, Aramaic, version to

work with. It seems to have been brought then to Jerusalem by Ananites from

Spain. He wrote two commentaries of the Pentateuch, which are called "the

longer" and "the shorter" one. This is, however very relative:. the "short" one

numbers 270 manuscript pages for Exodus XV - XXV alone! Of the longer

one less has survived, mainly on Leviticus.

He was influenced by the rationalistic theology developed by the

Mu'tazilites in Islam. He held that knowledge of the cre~tion cannot be

derived from Scripture alone, but is subject also to rational speculation. He

tried to define God and held that He, too, is bound by good and evil. Jeshua

tried to explain why God does good, though able to do evil, and what was

His purpose in creating the world. His line of thought is interesting and often

s,urprisingly modem ..

He and al-Basir broke with the tradition of their predecessors and

introduced the teaching of philosophy into the Karaite curriculum. This was

combined with the writing of philosophy in Jerusalem, of which he himself

was the outstanding practitioner.

In another field he tackled the difficult question of whom a Karaite can

marry without committing incest. Up to his time rules had been very strict, as

also the wife's family was held to be ineligible, and this because of the so40

called "rikkuv" theory, that man and wife form a unity of flesh (based on

Genesis 2:24). Thus also quite distant relatives of the other partner in the

matrimony became ineligible, as they were included in the biblical term

"'she'er". As the number of Karaites was never very large, this could have

had a negative influence on the sect's ability to survive. Thus a more lenient

ruling (which still was stricter than the Rabbanite one, and even more so than

the Samaritan one), was put forward, fIrst by Joseph ben Abraham ha-Kohen

ha-Roeh al-Basir, and under his influence, also by his pupil Jeshua ben

Judah. Blood relatives were thus reduced to parents, brothers and sisters and

their children. This was one of the most influential reforms to be introduced

to Karaite jurisprudence, and has been followed by most scholars - in spite

of their initial resistance - ever since18.

Joshua's influence was widely felt, among other reasons, because many of

his pupils settled in Byzantium. Such contemporaries of his as Tobias ben

Moses ha-Avel, and pupils of his, such as Jacob ben Reuben, laid the

cornerstone of the Karaite Center of Byzantium, which was to become

dominant in the Karaite world from the end of the eleventh century onward.

Jeshua was very influential also in Spain where Ibn al Tairas and his wife

were his pupils and friends19..

***

A few epigones were active in Jerusalem late in the eleventh century. Abu

el Hassan Ali ben Suleiman arranged and adapted earlier works by David ben

Abraham Alfasi from Morocco, by Aby al Taib from Tinnis in Egypt, by

Josef ibn Noah, by David ben Boaz and by others.

A member of the Tustar clan, saW ibn Fadl, or Jashar ben Hesed,

composed a comnentary on the Pentateuch and also treatises in the fields of

philosophy and Halakha. The following of his writings have survived: "AlTalwih 'ala al-Tawhid wa-al-'Adl" on philosophy, a treatise on incest and

another on Aristotle's Metaphysics. He lived in Jerusalem in the 1090's and

attacked fierc1y Jeshua ben Judah's conduct as a leader of the community.

His son is mentioned among the Karaite captives taken by the crusaders after

the 1099 capture of Jerusalem20•

Scholars of the Golden Age in places other than Jerusalem

Karaism was the product of an Islamic environment and till the twelfth

century flourished mainly in Arabic speaking countries. The Karaites were

41

1

using Arabic both as their spoken language and as their main literary

language. Jerusalem was the most important center of Karaite learning, but

not the only one. Their scholars were active also elsewhere in the Holy Land

and also in Egypt, Iraq, Persia and Morocco. Some of them travelled

extensively and it is difficult to know if they were active most of the time in

Jerusalem or elsewhere.

* Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Kirkisani, in the first half of the tenth century

hailed from upper Iraq and did not share al-Kumisi's attitude regarding the

central importance of settling in Jerusalem. His opinions are in many areas

very different from those of the scholars of the Holy Land and were

influenced to a great extent by the symbiotic cultural climate of Upper

Mesopotamia!. His principal work is a book of Karaite law, the "book of

Lights and Watch Towers"2. It is divided into 13 chapters and discusses such

legal subjects as the interpretation of the Law, the Conmandments, dietary

law, inheritance and legal aspects of incest (his strict views on this subject

were among those overturned a century later by Yusuf al-Basir and Jeshua

ben Judah). But other parts of his work range far and wide, from the

importance of rational investigations into theology to Jewish history. In a

separate part3 he discusses biblical exegesis. His many references to Anan,

Nahawendi and others make him the most important surviving source on

early Karaite history. Thus he speaks in his "Kitab al Anwar wal-Maraqib"

about "people of Anan", Karaites and "Benjaminites" as of three separate

sects.

His interests were catholic and ranged from the Koran and Arab

philosop~cal and scientific literature to the Talmud, Rabbinic liturgy, and

the New Testament. L. Nemoy has called him "the greatest Karaite mind in

the first half of the tenth century "4. Among his persoanal friends were

Rabbanites, Moslems and Christians.

He was opposed to the opinion of his contemporaries in the Holy Land in

that he believed in the importance of the study of philosophy. But large as he

looms in modern historical research, he had little influence on the

philosophic outlook of later Karaites. In his writings he relied on logic and

avoided the vituperations typical of some of his contemporaries. He believed

the study of the Talmud to be important, in order to fmd suitable material for

use in the polemics with the Rabbanites. As a result he was able to compile a

list of the differences in law and ritual between the Rabbanites of Babylonia

and those of Palestine. His moderation and common sense made him even

more effective as a propagandist of Karaism.

* Yaakub Yusuf al Basir, or Joseph ben Abraham ha-Kohen ha-Ro'eh,in

the first half of the eleventh century, lived in Persia or Iraq, but worked for

many years in Jerusalem. He was reported to have been blind and hence his

nickname "ha-Ro'eh", "the Seer". In spite of this affliction he travelled

widely.

In his "Kitab al-Tumayiz" and in his main work "al-Muhtawi" (The

Comprehensive) he tries to fmd the common denominator between Karaism

and Mu'tazilite rationalism. He stresses the rational character of ethics and

shows the priority of reason over revelation and study over tradition. He tries

to show that man enjoys free will, but God knows beforehand what his

choice will be. AI-Basir gives in his philosophy pride of place to the nature

of good and evil and to the question of God's justice. The Commandments

are His means of guiding man and those who follow them will be rewarded

in the Next World. He believed in accepting philosophy as a legitimate

subject matter in the Karaite program of instruction.

In his works he polemizes against various sects and religions, from

Epicureans to Christians and, of course, against Saadia Gaon. His opinions

and innovations on incest and the "Rikkuv" theory have been discussed in the

previous chapter, under Jeshua ben Judah. AI-Basir influenced decisively the

later Karaite philosophy and much of its cohesion is due to him. He died in

10405•

* Nissi ben Noah, lived in Persia, in the eleventh century. (Z. Ankori dates

him around 120(6). The "Sefer 'Asaret ha-Devarim", a philosophical

commentary, on the Ten Commandments (in the Firkovich collection in

Leningrad), has been attributed to him. Somewhat surprisingly he stressed

the importance of Karaites studying the Talmud and also other Rabbinic

literature. Another work by him, "Bitan ha-Maskilim" has been lost.

* David ben Abraham Alfasi came from Fez in Morocco, but spent some

years in Palestine. He was active in the second half of the tenth century. He

composed a Hebrew-Arabic lexicon of the Bible ("Kitab Jami al-Alfaz"),

which is one of the earliest and most salient works of this type, and most

important for the understanding of the development of Hebrew philology.

Modern philologists have accepted many of the parallels pointed out by him,

between biblical and mishnaic Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic. He classified

the roots of verbs according to the number of their letters and explained

many of them by metathesis, meaning the permutation of letters. Yet in his

own days his work exerted a limited influence only, and was soon

superseded by later compositions. His biblical commentaries have not

survived7•

43

42

•••

-

- -

~(r

ffI

._--

* Were the eminent masoretes, Moses Ben Asher and his even more

famous son Aaron, resident in Tiberias, in the ninth and tenth centuries,

really Karttites? Opinion among scholars is divided, with the majority now

negating this once widely held opinion8• The Ben Ashers worked out the

main elements of the system of Hebrew vocalization, which is still used

-., today. Aaron's "Sefer Dikdukei ha- Te'amim" is regarded as the foundation of

Hebrew grammar9.

-ilJ

fA.,1AiJ:ti

***

To summarize: The Karaite scholars of the Golden Age, both in Jerusalem

and in the Diaspora, are distinguished by the variety of their specializations

and opinions. Many of them were very outspoken, - not only when they

attacked Saadia Gaon. But they were mostly original thinkers, holding often

very different opinions. The wide field of subjects covered by them, from

philosophy to exegesis, law and grammar, is very impressive. They were not

overawed by the prestige of their own leaders, and were often prepared to

contest Anan's or Nahawendi's opinions, They were contemptuous of any

evidence of irrational thinking. In their view, ever since the catastrophy of

the destruction of the Temple, the contact with Divine Justice has been cut

off, and now each individual is on his own, and has to try as hard as he can to

reestablish contact. Rational thinking was regarded as his best tool in this

quest10•

The geographical spread of Karaism

Jerusalem was not the only Karaite center in the Holy Land. In nearby Ramie

a sizeable and important community is reported in the tenth and eleventh

centuries. Ramie had been founded by the Umayyads in the early eighth

century, and had served since as the regional capital of southern Palestine

(the province called Falastin). Jews settled there soon after and their presence

is reported by Arab geographers since the ninth centuryl. A local Jewish sect

is reported by Kirkisani, Hadassi and Makrizi, from the ninth century, named

"AI-Malkiah"

or "Al-RamIiyah".

They were supposed to have been

connected with the pre-Karaite Tiflisi sect. Their founder was usually called

"Malik a-RamIi"2.

Karaites are :f1rst mentioned in Ramie in the tenth century. Sahl ben

Mazliah speaks about their close relations with the local Rabbanites, and

their influence on them: - "Now should someone say "Behold our brethren,

the disciples of the Rabbanites on the Holy Mount (Jerusalem) and in

44

\

111....l._"

~

Ramlah are far removed from such deeds", then you must really know that

they walk the path of the (Karaite) students of Torah and do as the Karaites

do; indeed, they have learned it from the latter". He enumerates several

Karaite customs which they follow3•

Later on the Karaite community grew in size and frictions were reported

with the Rabbanites. The Karaites had at least two synagogues in Ramle, one

called "The Middle one", the other named after the Prophet Samuel. The

latter is mentioned in the colophone to a Karaite Torah scroll from 1013. A

Karaite document of divorce has survived in the Cairo Genizah, which was

prepared in Ramle in 1036. It is now at Oxford. The Karaites of Ramle are

mentioned also in other Genizah documents4•

The names of some of the central figures of the community have been

preserved. Thus Ali ben Abraham, called a-Tawil ("the tall one") wrote at the

end of the eleventh century a commentary on Scripture, called "Yerahmehu

ha-El yit'aleh". Israel Haramli is mentioned in a book of polemics against the

Karaites, dating from 1112. As by that time Ramie was in crusader hands, his

name indicates only that he hailed originally from that city. Jacob ben

Reuben seems to have lived for some time in Ramle, as he mentions in his

"Sefer ha'Osher" repeatedly features of that city. One of the copies of Japhet

ben Ali's commentaries

to Ruth and Canticles dated from 1084, was

especially copied in Ramle for the library of "the respected elder Abu alFaraj Ya'akub" (now in the British Museum)5.

On the advent of the crusaders in 1099 Ramie was left by its inhabitants,

including the remnants of the Karaite community. Nearly 900 years later it

was to become, in our days the seat of the Karaite World Center.

It is possible that there was a Karaite community in Hebron, south of

Jerusalem, and there still exist there remains of a Karaite cemetery6. Late

traditions of such a community were mentioned in 1786 by the Karaite

traveller Benjamin ben Elijah, from the Crimea7• However there seems to be

no trace of such a congregation after the end of the crusades8•

A Genizah document from 1052 mentions Karaites in Ghaza, who helped

in the fixing of the calendar for that year by reporting on the state of the

barley harvest in the vicinity9.

Another document, from 1050, mentions Karaites in Sebaste (the ancient

town of Samaria)lO.

The presence of Karaites in tenth century Tiberias (the capital of northern

palestine, called Urdun - Jordan) depends on the thorny question if the Ben

Asher family was indeed Karaite, on which we have touched in the previous

45

,

__

>---

~-

_

-~

J.

I

chapter. Otherwise there are at present no signe of a Karaite community

therell.

One of the Genizah documents was written by a Karaite refugee from

Acre, after the city had fallen to the crusaders, showing that at least a few

Karaites must have lived there before its capture in 110412. In another

document, this one from 1051, (a marriage contract) Karaites are mentioned

in Tyre13.

Kirkisani mentions early in the tenth century Isawites in Damascus, who

might later have merged with the Karaite movement. In the eleventh century

the Karaites of Damascus sided in the struggle for the Gaonate of Jerusalem

with the usurper, Nathan ben Abraham, against the Gaon Salomon ben

Jehudah. This is what Nathan himself reports. It has to be taken as an

indication that the Karaite commnunity of Damascus was quite sizeable. In

the eleventh or twelfth century a branch of the House of Anan established

there a seat of the Nesiut (Patriarchate), which continued to exist for over

five centuries. Around 1040 a Genizah document was written by a Karaite

weaver living in Damascus14. After 1099 some of the survivors of the

massacre in Jerusalem by the crusaders, appear to have moved to

Damascus15.

Another community existed already in the tenth century in Aleppo, and the

polemicist Salmon be Jeroham spent his last years there. His grave was still

venerated in the fifteenth century. The local community adhered to the

Jerusalem type of calendar.

It is possible that Karaites lived also in Armenia, in addition to the local

Tiflisite sectarians, who are mentioned there in the ninth to the twelfth

centuries.

An important Karaite community is reported from the tenth century

onward in Fustat, and later from nearby Cairo, the capitals of Egypt under

the Tulunids (868-905), Fatimids (969-1171), Ayyubids (1171-1250) and

Mamluks (1250-1517). Some of its members were influential enough to have

a Rabbanite synagogue closed in Fustat (1039)16 and to have been able to

help the Karaite community of Jerusalem1? One of its leaders was in the mid

tenth cennuy the above mentioned Salmon ben Jeroham.

In the synagogue in Fustat named after Ezra the Scribe, which appears to

have been originally in Karaite hands, the famous Genizah was discovered at

the end of the nineteenth century. Among its hundreds of thousands of

documents and fragments there are therefore many which mention the names

and occupations of contemporary Karaites, from the tenth and eleventh

centuries onward. A typical Karaite occupation was for instance that of

46

moneychanger and moneylender, who had their stands in the market of the

goldsmiths18.

Another of their synagogues was destroyed by the fanatic Fatimid khalif

al-Hakim (996-1021), who persecuted Christians, Rabbanites, Samaritans

and Karaites indiscriminately19.

The Fatimids founded Cairo immediately north of Fustat soon after their

conquest of Egypt. The Karaites settled eventually in its eastern quarter,

Zuwayla, where also most of the Rabbanites were concentrated. Fustat was

destroyed by fire in 1168, set by the Egyptians themselves, during their wars

with the crusaders. It was never fully restored. The Karaite community of

Cairo continued to exist till nearly the end of the twentieth century, often as

one of the main Karaite centers20.

Other Karaite communities of Egypt are mentioned in a document from

1028, in Damietta (the harbour on the main eastern branch of the Nile),

Tinnis (further east, on an island in Lake Tannis) and Sahragt. Tinnis was the

stronghold of the Tustar clan, who wielded great influence at the court in

Fustat.

Further Karaite communities existed in some of the cities of the Mughreb.

The above mentioned David ben Abraham Alfasi hailed, for instance, from

Fez in Morocco. A Genizah document from the middle of the eleventh

century is addressed to a Karaite in Tripoli21, and one from 1030 mentions

Karaites in Caiman in Tunisia and in the oasis of Quargla in Algiers22.

Some members of Anan's family are reporrted to have settled in Spain and

to have still been there in the eleventh century. Till about 1100 the Spanish

Karaites appear to have followed the Palestinian practice of computing the

'alendar, but afterwards they changed over to the Rabbanite practice23.

The first report of Karaites in Constantinople is dated from 102824.Further

information about the early Karaite settlement in Byzantium can be found at

fhe beginning of Part III.

Most Karaites lived apparently at the beginning of this period still in Iraq

IIld Persia as indicated by the backgrounds of some of the outstanding

Hcholars. Thus Japhet ben Ali Halevi came from Basra, Kirkisani from Iraq,

Yw;uf al Basir lived in Persia, saW ibn Fadl might have come from Shustar

II P0fsia, Nissi ben Noah lived in Persia, etc. Kirkisani mentioned early in

tlill jonth century Karaite comnunities in Baghdad, Basra, Fars (in southern

1'(111'111), Khorasan (south-east of the Caspian Sea) and Tustar (north-east of

IIlIMlI)7A , Bull'here certainly took place a slow movement of Karaites westwilid.

47

The Karaite Nesiim (Patriarchs)

The backbone of the Ananite sect were the descendants of Anan. Mter both

sects had amalgamated, Anan's descendants were accorded for many

generations by all Karaites the title of "Nasi" (which has been translated as

"Patriarch", but their function was more that of secular leaders, than this term

would lead one to believe).

Later sources mention already Anan's son Saul and grandsons Josiah and

Daniel as Nesiim. But in reality the fIrst generations of his descendants

appear to been Rabbanites in good standing. His great grandsons, Josaphat

and Tsemah even have headed in the ninth century the Rabbanite "Academy

of the Land of Israel" in Tiberias, holding the title of Gaon1• Tsemah's sons

Asa and Jefet were not allowed to continue as Gaonirn, apparently because

they were regarded already as sectarians, showing that by the middle of the

ninth century the break was already complete.

Somewhat earlier, in the fIrst half of the ninth century, a grandson of

Anan, Daniel (the brother of Josiah, the father of Josaphat and Tsemah)

competed still for the title of Exilarch, but was defeated, as mentioned both

by Natronai Gaon and Michael the Syrian. The latter calls him already an

"Ananite". Natronai claims that he spoke up against the Mishnah and

Talmud, and in favour of the "Talmud" written by his grandfather Anan2• His

son Anan the second lived in Jerusalem.

Josaphat's son Bo'az is mentioned in the Genizah documents about

Bustenai. The names of two of his sons have been reported, David (Abu

Sa'id) and Josiah (named after his great-grandfather). They are mentioned,

somewhat surprisingly, as belonging to the camp of Saadia Gaon, by the

Gaon of the Babylonian Pumbedita Academy. This places them early in the

tenth century and shows that even by then the lines between Karaites and

Rabbanites were not drawn as clearly as one would have expected (but this

applies perhaps more to Ananites and especially to Anan's descendants, than

to others). Another source mentions David still in 993, by which time he

must have been a very old man. We have mentioned him also in our list of

Karaite scholars living in Jerusalem. His relations with the Gaon of the

Jerusalem Academy were strained and this might have caused his

rapprochement with Saadia Gaon, though he disagreed with him on several

points, as shown in his commentary on the Pentateuch3.

Also David's son Solomon lived in Jerusalem, as mentioned in a document

from the Firkowich collection, which places him there in 1016 and mentions

also his two sons Josiah and Hezekiah. These two seem to have lived,

however, most of their lives in Fustat, but had strong ties to the Jerusalem

community. The title of Nasi was held in Fustat, initially by the descendants

of Tsemah, Asa and Jephet. Only after the death of Asa's son Tsemah and

grandson David, did Hezekiah inherit the title of Nasi in Fustat. The later

Nesiim there were all his descendants4•

Yet in the colophon of the Aleppo "Keter" both brothers, Hezekiah and

Josiah, are mentioned as Nesiim. A letter of the Gaon of Jerusalem, Salomon

ben Judah, to Hezekiah has survived, dating from about 1026, in which he

invites him to come to Jerusalem, in order to help him in his struggles against

his adversaries there, illustrating the close relations which existed at that time

between the Rabbanite and Karaite leaders. In this and another letter there

are hints that the Karaite Nesiim of Fustat had at their disposal considerable

sums of money, some of which they spent on their co-religionists in

J erusalem5 •

The Nesiim were in Fustat in close contact with the powerful Karaite

Tustar clan, and one of the Tustars married the daughter of Hezekiah or

Josiah (the marriage contract has survived in the Genizah, with the name of

her grandfather, Salomon, but not of her father)6.

The following is a partial family tree of the Nesiim

Anan

I

Saul

I

I

I

Josiah

I

I

Josaphat

I

Asa

I

I

David(Abu Said)

I

Josiah

1

Anan

Jefet

"

Josiah Tsemah

I

Salomon

I

I

I

Tsemah

~I~I_~I

Boaz

I

Daniel

David

I

Hezekiah

In later poriods the title used in Fustat was "Nasi of Israel and Judah". Also

the title Exilnrch was used by some of Anan's later decendant's in Egyptdown to the Novcntcenthcentury7.

1\9

48

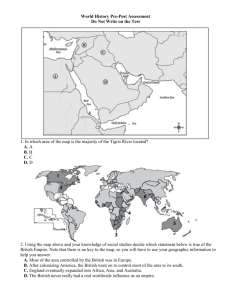

Problems of the Karaite Calendar

One of the areas of greatest discrepancy and friction between Karaites and

Rabbanites Was that of the calendar, and that for obvious reasons: the

adherence to a specific calendar was the real criterion of one's

denominational identity. Kirkisani reports, for instance, that Rabbanites in

Damascus were prepared to intermarry with Isunian sectarians, who regarded

both Jesus and Muhammad as prophets, but did not differ from the Rabbanite

calendar, while they were not prepared to do so with Karaites, who did differ

in ,!be timjng~oftheir days of festivall.

The Rabbanite'ealendar was b;ythat time-precalcUlated and only rareIyhad

to be tinkered with. KaraiSill'represented in this, like in many other fi~lds;--a

conscious a.ttempt to return to~asimpler, earlier Judaism. The ripening of the

ears of barley_in the Holy Land wls regarded as the sign for the advent of

spring ("abib") and thus of a new calendar year. If there was any delay,

intercalation became necessary and religious festivals took place on quite

different days from those of the Rabbanites. Each party was thus forced to

desecrate the days held to be holy by the other.

This was made even more problematic by the Karaite insistence to base

the beginnings of each month ("Rosh Hodesh") on actual lunar sightings.

Its different calendar, more than any of its other outward features, gave

Karaism its mark of institutional separatism, resented by the Rabbanites.

Adherence to it was regarded as so important, as to be included even in

Karaite marriage contracts, examples of which have survived both from

Jerusalem and from RamIe. From Egypt the text of an interdenominational

"Ketubah" has come down to us, showing that in the case of a marriage

between a Rabbanite man and a Karaite woman, her rights in this respect

were insisted upon2• Incidently, the Karaites demanded that the text of a

Ketubah had to be in Hebrew, which the Rabbanitelidid not.

The Karaite system necessitated the presence of Karaites in the Holy Land

in order to carry out the necessary observations. The "Mourners of Zion"

thus appealed for settling there, as a prerequisite for full redemption, partly

because of the requirements of the calendar. AI-Kumisi claimed that a return

to Zion would enable the pious to observe properly the ripening of barley and

would thus eliminate a source of sin that delays Divine reconciliation with

Israel.

It was further necessary that the observations should be transmitted to the

Diaspora immediately, - which was not always easy, because of the insecure

\III

and turbulant state of Palestine during much of the tenth and eleventh

centuries.

Thus in Iraq Karaites often computed the calendar on similar lines to the

Rabbanites, instead of making use of the sightings of "abib" in the Holy Land

- a practice condemned by such Karaite scholars as Levi ben Japheth, who

was, however prepared to soften somewhat the rigid position of earlier

Karaites such as al-Kumisi.

Another difficulty was, that the Karaites of the Golden Age in Palestine

were no longer agriculturists, but rather city dwellers. As wars and revolts

engulfed Fatimid Jerusalem, it was difficult to find nearby barley fields to

watch. Hence the complaint by Levi ben Japheth "Now those who preceded

us (followed the abib) on the basis of their own actual acquaintance with, and

knowledge of the seeds, since they themselves cultivated and inherited the

soil. Thus, they used to inform each other (of the state of the crops) and (their

prognosis) would be unquestionably correct. (Nowadays) all these things

have become difficult for us, since all the land is not ours and most of us are

incapable of recognising the seed "3.

As the position in~Palestine became even more difficult, after the Seljuk

capture of most of the country in 1071, Karaite scholars in the Diaspora

found it increasingly difficult to await instructions, as shown by the letters of

Tobias ben Moses from Byzantium. The answer he recerved from Jerusalem

(perhaps by Jeshua ben Jehudah) was to follow in the meantime the

Rabbanite way of calendation, but after the receipt of instructions from the

Land of Israel, to follow them as well, even if that meant to observe a festival

twice .

. Mter the disappearance of the Karaite community of Jerusalem in 1099,

the situation became even more problematic. The Karaite principle was not

given up, but in the twelfth century the tendency in the new center of

Byzantium was to follow the Greek Orthodox computation, in order not to

have Passover precede Easter, which would have incurred a prohibition

(dating from the time of Justinian) of its public celebration.

The Karaites of Egypt, Syria and Palestine continued to follow their old

system, but those of Byzantium accepted during the following centuries the

Rabbanite computation on a de facto basis, till a difference of a complete

month had opened up by 1336. The fifteenth century leaders of the Karaites

of Turkey, of the Bashyazi family, accepted the Rabbanite 19-year cycle

officially, though upholding for appaerances' sake the fiction that this was an

ancient Karaite legacy4.

50

51

This solution was later copied in the Crimea by Simha ben Solomon

Babovich (1790-1855).

Karaite customs

On dietary laws the differences with the Rabbanites in tenth and eleventh

century Jerusalem was even more marked than they are today. Now they

differ on the detailed regulations of ritual slaughter and the Karaites regard as

a result the meat of animals slaughtered by Rabbanites as prohibited. But alKumisi regarded all consumption of meat as sinful, as long as there were no

sacrifices. He prohibited even the consumption of fown. Kirkisani stressed

that these prohibitions applied only to Jerusalem, but that properly

slaughtered meat could be consumed elsewhere2• An anonymous Karaite

Genizah document, published by Schechter, prohibits both the consumption

of meat and the drinking of wine3• saW ben Mazliah quoted several instances

of Rabbanite laxity and demanded, too, that no meat should be consumed

while Israel is in the Diaspora4• To him and his contemporaries thelDiaspora

was not a geographical term, but a definition of the situation of all Jews since

the destruction of the Temple, wherever they might be, - even in Jerusalem.

Friedlander believed that these strictures have their roots in Manichean

influences5•

The Karaites were less strict than the Rabbanites on the Biblical

prohibition of "boiling a kid in its mother's milk" (Ex 23: 19; 34:26; Deut.

14:21). Solomon ben Jehuda reported in the eleventh century that Karaites do

eat meat with milk. Further he related details of a dispute between

Rabbanites and Karaites in Ramie on this subject, as the Karaites refused to

accept Rabbanite supervision6• But in Jerusalem disputes on this subject

seem unlikely, as the consumption of meat was prohibited anyway. In later

periods however, there is more evidence of this Karaite custom7• Mter the

rapprochement with the Rabbanites in Byzantium, Karaites, too, were

prohibited to consume meat of cattle with milk or butter, - but not that of

fowl.

The customs of ritual impurity were far stricter among the Karaites than

among the Rabbanites, but there was (and is) quite a bit of similarity to those

of the Samritans. The impurity of the menstruation period necessitates the

segregation of the woman concerned in a corner of the house.

Karaite circumision (like Samaritan circumcision) is less far reaching than

the Rabbanite custom. Peri'ah and mezizah are rejected by the Karaites,

resulting in an incomplete removal of the foreskin.

Karaite prayers consisted originally mainly of the Ma'amadot (prayers

referring to the Temple sacrifices). Later the custom of two prayer services a

day (morning and evening) was generally accepted (Rabbanites observe

three). Only on the Sabbath and on certain festivals is the Musaf prayer

added. Prayers must consist of seven parts: shevahim, hoda'ah, viddui,

hakkashah, tehinnah, ze'akah and keri'ah, and in addition the confession of

faith. Most of the prayers consist of passages from the Psalms, or from other

parts of the Bible. But also prayer-poems are included, which are unknown to

the Rabbinic rite. The Shemonah-esreh prayer is not used by the Karaites, but

the Shema is included in their rite.

Karaite liturgy consisted originally only of biblical psalmody, and is quite

unlike its Rabbanite counterpart. The haftarot selection of the Karaites, too,

differs widely from the Rabbanite one.

During public prayer Karaites do wear a fringed garment, the zizit of

which includes a blue threat. They do not use tefillin and affix the mezuzah

only to the gate of a synagogue, but not to that of a private dwelling. Inside

the mezuzah they have the ten commandments.

In matters of inheritance the Karaites diverge too from the Rabbanites.

According to al-Kumisi, daughters are entitled to inherit a third of the

inheritage, and are not discriminated against relative to sons9• Kirkisani

claimed that this precept goes back to the Ananites, but personally opposed

it10• There were other Karaites as well who opposed it, as shown in a Cairo

court case of the tenth centuryll. Karaite marriage contracts differed from

Rabbanite ones at that time. If a woman died childless all of her dowry was

to be returned to her father's household, while Rabbanites stipulated that only

half of it was to be returned12•

Another Karaite stricture was the baking of Matzot from barley instead of

from wheat, as customary among Rabbanites8•

The customs of marriage and the problems of the theory of incest and of

"rikkuv"

dation. have been described already, and so have the practices of calen-

The polemic against Saadia Gaon

Rabbanite Judaism was influenced by much the same ideas as were the

Karaites of Jerusalem and Iraq. Thus Saadia (882-942), too, can be said to

52

3

Ul,

I/!

have belonged to the rationalistic school of the Mu'tazilites and was

influenced by Aristotelian philosophy. He, too, attempted. to reconcile

Scriptue and philosophy, reason and revelation. If so, why was the

disputation between him and the Karaites so bitter?

The reason has to be looked for in the very similarity of their assumptions,

while they were separated by their different attitude to Oral Law. Saadia

believed that human rationality is reinforced in its attempts to understand the

Divine will, by both Written and Oral Law!. The latter was, of course,

completely unacceptable to the Karaites. They regarded him as especially

dangerous because otherwise their views were so similar.

III

I

I

The fIrst shot in the polemic was fIred by Saadia, when only 23 years of

age, by issuing a responsum to Anan. This caused most Karaite thinkers to

concentrate their fIre on him, - none more so than Salmon ben Jeroham. In

his "Milhamot Adonai" Salmon crystallised the Karaite case against Saadia

in fIfteen main points, every single one of which turning on the question of

Oral Tradition. Just as a sample, number nine: in the Mishna we fInd that the

schools of Hilel and Shamai disagree, - if so, whose opinion are we to

accept?

number

if the Mishna stands in need of further commentary,

how

can Or

it be

God's ten:

teachings?

In other parts of his work Salmon attacks some of the customs of the

Rabbanites (such as having two day festivals in the Diaspora) and holds up to

ridicule

the Agadot (legends), which were of course, also a part of the text of

the Talmud2.

In previous chapters we have mentioned other Karaite scholars, nearly all

of whom attacked Saadia in one way or another, though usually in a more

restrained tone, than Salmon ben Jeroham. Nearly all of their arguments, too,

did not concern Saadia's basic philosophy, which was similar to their own,

and turned instead on the use of Oral Law. Saadia's commentary on Leviticus

is the Rabbinic text most vigorously attacked by Karaite polemicists. In

Leviticus are concentrated most of the laws, such as the code of purity, the

calendar of feasts, laws on incest and dietary prohibitions, over which

Karaites and Rabbanites disagreed.

Later Karaite scholars, less creative than those of the Golden Age, did not

have the wide philosophical scope of their predecessors (or of Saadia) and

usually only repeated the main arguments used already in the tenth and

eleventh centutries. The question of the Oral Law continued as the be all and

end all of these polemics throughout the ages.

What was the real importance of Saadia's role in this struggle? It has been

differently 'interpreted by different scholars. "While some would credit him

with warding off the danger of "Karaization" of all Jewry, others would

consider precisely his attack the decisive factor in uniting and consolidating

the otherwise weak and scattered sectarian forces"3. Z. Ankori has suggested

that he has to be regarded as the most important representative of Babylonian

supremacy in its struggle with the danger of "the equation of Karaite counterinstitutionalism with the cause of Palestine in her contest with Babylonia"4.

It seems however clear enough that Saadia did alert Rabbanite Judaism to

the danger of Karaite encroachment. He and his successors did succeed to

limit the sectarian ferment and to prevent it from endangering all of Judaism.

Eventually they confined Karaism to the role of a relatively small minoritysect.

From the tenth century onward the Karaites regarded themselves as "the

righteous few struggling in a commnunity of sinners", thus expressing the

Karaite "minority complex" which prevades much of their later work. They

admitted thus, inadvertently, the failure of their attempt to take over Judaism,

and their basic awareness that their sect was doomed to remain only a small

segment of the Jewish people. This basic fact has not materially changed in

the long period since5.

1099 - the Advent of the Crusaders

The Golden Age did not end, like so many others, in slow decline, but by one

act of war, the capture of Jerusalem by the crusaders. On June 3rd, 1099, the

crusader host reached Ramle and found it empty. Together with the

Moslems, also her Karaite inhabitants must have left, and, as we shall see

luter, seem to have made their way to Ascalon, which remained in Fatimid

llllnds for more than half a century.

The crusaders continued to Jerusalem, which they reached June 7th and

(lllptured July 15th. Most of the Moslem and Jewish inhabitants were

IIIllssacred, but the Fatimid governor and the garrison were allowed to

wll'hdraw. The Karaites seem to have been relatively lucky. Their quarter

Wllll outside of the city walls, and thus many must have fled on arrival of the

I 11iNaders,and_thus saved their lives.

A detailed letter~'apparently from Alexa'ndria, has survived! which shows

t the number of Karaite survivors was sizeable. It was written about aye!!!:

the capture of Jerusalem and by that time most of the Karaites were in

lion, Jiving under very strained conilitions. A few were still held for

!ll~~()mby the crusaders (apparently by Godfroy of Bo~lon's LOtharingians,

54

55

~

as the ...--letter speaks abou~damned Germans"). A few,

~ who had fled into the

cIty of Jerusalem onarrival of the crusaders, had been abl~to come out with

the garrison~None of the Karaite-women had been raped by the GermanJ.

Quite a few of the Karaites had fall~n-into the hands of the crusaders and

were held for ransom. Some had died already, others were said to have been

kil~pUFpose.

Luckily the crusaders were not aware of the going rate for

Jewish prisoners (three for a hundred dinars) and asked for much less. Thus

the limited resources of the Karaites were still sufficient to release some

ru.rtlier ~s, but not all. The Karaites handled this problem alone, without

cooperation with the Rabbanites. The center of the relief action was

app$..e~tly.in Alexallilria, but the money came mostly frOI!!.the large Fustat

community.

Most of~those who had been released died of exposure and an unidentified

epidemic. Others perished during the sea voyage (presumably from Ascalon

to Alexandria). No Karaite physicians seem to have been available in

Ascalon, as expenses for medical services are mentioned. Mainly the poor

prisoners were initially released and had to be supplied with food and

clothing, while the crusaders still kept the more valuable, rich ones. Among

them was a boy, whom they tried to convert to Cluistianity, but at the time of

writing he was still holding out, exclaiming "how can a Cohen become a

Christian?"

Many of the religious books had been bought back from the crusaders, 230 bibles, 100 codexes and 28 Torah scrolls. The total expense for prisoners

and books had been, at the time of writing, 700 dinars. The author of the

letter demanded urgently more money, in order to continue with his activity2.

In another letter from the Genizah3 a Karaite refugee writes in 1115 from

Fustat. He had come from the port of Acre, had fled to Alexandria, and

complains about the community there. He writes to an acquaintance and

requests his help. This letter shows that even several years after the advent of

the crusaders, the Karaite survivors found their new lives fraught with

difficulties. Acre had fallen to the crusaders five years after Jerusalem and

was destined to become under their rule the biggest and richest town of their

kingdom. In the thirteenth century a sizeable Jewish community grew up

there, but so far there are no signs that any Karaites lived there4•

In the end most of the surviving Karaites from Palestine ended up in

Egypt, but a few reached Damascus5• During the 200 years of Christian rule

in Palestine or parts of it, there was no real chance to renew the Karaite

community of Jerusalem, and even when it was renewed, in the late

thirteenth century, it continued to be a small congregation of little

importance, with no pretension of renewing its dominant position of the

Golden Age.

57

56