PRELIMINARY - University of the Witwatersrand

advertisement

KOEBEE ROCK PAINTINGS,~

~~~PRELIMINARY

ON THEREPORT

~

WESTERN

17

South African Archaeological Bulletin

South African Archaeolosgical Bulletin 48: 16-25. 1993

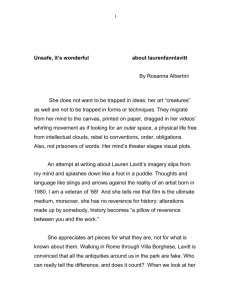

Table 1: Frequencies and percentages of male, female and indeterminate human figures in two samples recorded in the

EE ROCK PAINTINGS, WESTERNKoebee area. Data from sample 1and 2 are summated in the final two columns.

CAEPRELIM

ONRCA

THE~

INARYN

KOE

REPSORT

CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA*

,.

JEREMY HOLLMANN

s'8'3-

i

FEMALE FIGURES

SEX INDETERMINATE

i

\C~

,.- . „ *' 'TOTAL

} ,~ ~

a o rta yed%"

ive froam 50sites. erHupain ^s

in r hie portcdrco

species. Paintings of animals are limited tina restrictedmal

antelope.{

is antelope.

of which

of

rnetge

rangespecies

of species,, of

which the

the majority

majority is

-,--=

Symtbols, meteaphors and postures associated with San

dances,

occur. There are depictions

of healingalso

Thraeeictosohalndacs

a.~._aok..

fIk~,...

a complex fight' scene,

rufat

tailed sheep andriruasalsoceur

'

* * ' "

^-^

/ i

*...

Janus"~

Receivedn~

1993,~ Se. mber~~ 1992.~ rese

*Received

September 1992, revised January 1993

~rin~utabls

southern Drakensberg. M en are commonly depicted in

same sex 'processions' and groupings with hunting

equipment, in dance scenes, associated with animal

'\

and, less frequently, with therianthropes.

m

\

»images,

In one of the processions, painted on top of what are

probably the remains of two yellow

.... antelope,.- three men

1

*%

at~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~carry bows and/or quivers (Fig. 2). Seven carry whisks,

the !Kung use in ritual dances (Lee 1967; Marshall

,which

1969; Katz 1982). The men have the 'hookheads' so

widespread in the western Cape; traces of white on the

faces of some of the figures show that all the images were

.

...

probably originally bichrome. Some of the figures have a

'.

*

»penis.

~

32·*0

"

Although the area was explored by Godfrey and

Marjorie Hoehn in the 1960s (see also Van Riet Lowe

1956), the paintings of the Koebee River valley and

Fig. 1. Map showing the Koebee area and other localities

mentioned in the text.

surrounding mountainous highlands (Fig. 1) are under

researched compared with those in some other parts of

southern Africa. Humphreys er al. (1991) have described

an area to the east of the Koebee River, and rock art on the

Gifberg has been recorded by members of the Spatial

Archaeology Research Unit (SARU) of the University of

Cap Town

(Yates pers comm.). Areas south of the

Capeown

Ises.Yate

cmm.) Ares soth o the

Doring River have been extensively documented (e.g.

Yates

Yates et al. 1985)

1985).

The present survey located 50 painted sites in the

Koebee. Thirty-eight sites (sample 1) are on four

neiehbouring

neighbouring farms

farms approximately

approximately 55 km north

north of

of the

the

confluence of the Koebee and Doring rivers. Twelve sites

(sample 2) were recorded approximately 25 km north of

sample 1. All sites were plotted on 1:50 000 maps, and

notes and sketches were made at each site. Tracing was

necessary, particularly where environmental factors had

obscured much photographable detail (see Loubser & Den

Hoed 1991 for a discussion of tracing as a recording

method). The rock surfaces in question are, however, not

friable, and the chance of damage was considered

minimal. In addition to tracings. 35 mm colour slides and

black

nd whie

were

aken.(Vinnicombe

black and white phoograph

photographs

wereertaken.

taken.\

black

nd whie photographs were

features in c1975),

The Koebee

have paintings

certain fePakhuis

with rock art in other parts of southern Africa, but there

are also some differences. The significance of these

similarities and differences is not well understood; they

will have to be assessed in terms of the 'meanings' I

outline here and the specific historical trajectory of the

Koebee.

ae

-

b mnh

found. Many images that now appear to be monochrome

wereproabloriginally

orginllybichrome,

or,

were probably

bichrome

or, gossibly,

possibly,

polychrome (see Yates et al. 1985:70 for further

discussion).

, As in other areas, the paintings in the Kotbee are

characterized

by the

selective,

and

repetitive

nature'

of their

subject conventionalied

matter (Vinriucomber

1p76:5 nature of thersu9 ect mtter (VPn;lbcombe

t

1967; Vinnicombe

Pager 1971b; 1972;

Smits'Yates

1971;

1976:350;

see Maggs

Lewis-William~s

1972, 1974;

et

er

Vcl

l 1972T Yares o

Lew1s-Will8ms 1972s 1974; ins).

. 1985 for similar conclusions). The repetitive nature of

~~~~~~~~Koeb

~~case).

Patterns in Paintings

Most of the images are monochrome, red being the

most favoured colour. A small proportion are red and

white bichromes. No polychrome paintings and only a

very small number of yellow and black images were

%

SAMPLE 2

(12 SITES)

COUNT %

TOTAL

%

COUNT

103

111

214

44

16,8

18,1

34,9

7,2

35

22

57

11

14,3

9,0

23,3

4,5

138

133

271

55

16,1

15,5

31,6

6,4

355

613

57,9

100

177

245

72,2

100

532

858

62,0

1.00

"il

.TsL^cc

in this report derive from 50 sites. Humans are portrayed

:I

penises

bows/quivers

total male

breasts, steatopygia

no distiguishing

gender characteristics

MALE FIGURES

e/

"""**

Little systematic recording of rock art in the Koebee area

of the western Cape has been undertaken. Data presented

Introduction

CATEGORY

~.

,"

U.nrn,,..«.r.

^ ¥

ABSTRACT

-

,"

'

Rock Art Research Unit, Department of Archaeology

University of the Wirtwatersrand, Wits, 2050

SAMPLE 1

(38 SITES)

COUNT

the art over extensive areas is consonant with the notion of

a 'pan San cognitive system' (McCall 1970; Lewisthat is, 'aa set of conYates

et

~Villiams

Wllms 1981a;

1

te

e al.

a 1985),

15

nshape

Let and perceptions of the world that unif all ock art,

ritual and trance experiences of

and

the

mythology

prehistoric andcontemporary San" (tYates et el. 1985:70).

S

(

. 950

.indicate

Gender in the Koebee rock art

Researchers elsewhere in southern Africa have noted

that the paintings 'reflect a distinctly masculine bias

(Vinnicombe 1976:245; se also Pager 197a, 1971b,

1976:245; see also Pager 1971a, 1971b,

^ ^a similar bias in the

and Maggs (1967) recorded

area 60 km south of the Koebee. Quantitative data

from the Koebee (see Table 1) also show numerical male

dominance. Paintings of naked males comprise 16,1% of

humans; it is assumed that figures with bows and/or

quivers (15,5% of total) also represent men (see, however,

Solomon 1989 for argument that this is not always the

Figures with breasts account for approximately

6,4 % of human figures. The ratio of male:female figures

identified by the criteria given approaches 5:1.

Apart from certain dance scenes, men and women are

generally depicted in separate groups. This appears to be a

characteristic of San rock art; Vinnicombe (1976:352)

comments on "the repeated association of mun with

hunting equipment and women with digging stick." in the

sex groupings and 'processions', sometimes with digging

sticks. Paintings of steatopygous females (Fig. 3) have

s

been interpreted as connoting concept of nakedness

symbolically associated with "eland mating, girls' puberty,

fat, potency, goodness and social harmony" (Yates et al.

Lewis&Fig. 11; see also Biesele 1978:923-924;

1985:79.~."~

...

I

Williams 1981a:41-53;

Solomon 1989 for related

discussion). Paintings of women with sticks are also

common in the Koebee, occurring in mixed dance scenes

and in smaller all-female groups. The postures of some of

these women suggest that they are dancing (see Bleck

1935:12 for ethnography relating to dances and sticks).

The significance of the relationship between female and

-

\

.(

'

l

D

.

'

.,

~.2

%

Parkington has observed that in paintings of men in the

Cedarberg "penises are commonly depicted, often

exaggerated and sometimes attended by scrota" (1989:14).

In the Koebee. figures with semi-erect penises (Fig. 2),

'infibulation' (Fig. 4) and disproportionately long

penises/emanations from the groin (Figs 5 & 9) were

penises/emanations from

the groin (Figs 5 & 9) were

found. These figures occur in healing dances, (two

instances), and in 'processions' and groupings of male

figures (three instances).

As is the^ase elsewhere in the western Cape (Yates et

nl. 1985:79) and the southern Drakensberg (Vinnicombe

1976:246), women are often depicted in a 'clapping

posture' (Vinnicombe 1976:246 & 310; Biesele 1978:927;

Lewis-Williams 1981a:76) in dance scenes, and in same

F

2 Processon of male figures Note the scklike

h aklk

rcsinowhich five ae

upon

of theiue.Nt

figures are superimposed.

Itthsbe

has been suggested

that paintins

hssr a of this sort may

htpitnso

ugse

imply directionality, being read from left to right

(Solomon 1989). Areas enclosed by dotted lines

rock flakes. Solid: red; stippled: yellow;

white: unshaded, enclosed by solid line. Scale in this

and subsequent redrawings is in centimetres.

male images needs to be examined. Solomon (1989) agrees

with earlier writers that the art is dominated by a

masculinist principle, but cautions; ,ht this cannot simply

be inferred from quantitative data. She proposes a gender

taxonomy that

that organises

organises 'rock

"rock art,

art, narrative,

narrative, material

material

culture and spatial organisation" (1989:94) and argues that

the masculine:feminine opposition was used to make

statements about central concepts of fertility, prosperity

and order. Solomon suggests that, "overall the metaphors

and taxonomy are implicated in the differential valuation

and positioning of men and women in the San symbolic

order, to asymmetrical valuations of the genders, and

hence to ideology" (1989:76-77).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~taxonomy

South African Archaeological Bulletin

18

South African Archaeological Bulletin

SouthAfrian

,H^B& F W *7Pig.

-recalls

^H^^Mf~f

5^ff^~~

;HdI~

:

C

~~

^Wistrokes

If-shoulder

Fig. 4. Male dancers. One figure holds a whits stick and

there are white 'bars' across their erect penies. Similar

are around the buttocks and emanate from the

rhelgia

5. Healing dance. The inverted figure on the right

descriptions of San dance participants who turn

somersaults, reportedly as a result of fiercely boiling

potency. Paintings similar to the two horizontal figures

in the centre of the dance scene have been interpreted

as copulation, but the healing context depicted here

u

suggests that the images might relate to healing

practices observed amongst the !Kung: healers

maximize their contact with patients by lying on top of

them (Katz 1982). Stippling represents varying

densities of red paint.

of the right-hand figure. The langitudinal

tracks of white dots on the torsos may represent sweat,

which the !Kung believe to have magical/healing

·

Fig. 3. Steatopygous woman with stick. Note the white

paint at the wrist, elbow, waist, knees and ankles,

Note

the odepiction ofa dance

properties.

epciratlves

o prpris

aon

noeth

c rattles around

their calves/

which probably represents ornamentation. There are

two enigmatic white dots above the figure's head. Stip-'

'/y'

Animal Images

pled areas represent faint traces of red paint.

Although there

, cr j ,Jff

. i. .

i *. ..

r ,.

longitudinal tracks of dots on the torsos,

the

sprays of dots

frm th

around

thebuttocks ando th lineo eaie

she

a

ro un d

and

""*''"ttock~~~~nd

Shamanism he line emanating romthe

of the right-hand figure have been 'endered in

an Sham

Healingansmshoulder

The importance of healing dances in contemporary and

while paint.i

.

historical San societies is well documented (e.g. Lee 1967;

In the second group (Fig. 5), at least five of the images

Marshall 1969; Biesele 1978; Katz 1982). Lewis-Williams

have been rubbed or smeared (see below). Five of the

has referred to the '/Xam preoccupation with medicine

figures have their arms raised in what the ethnography

men' (1981a:75), and the /Xam ethnography shows that

suggests is a dance posture (cf. Fig. 4). Seven have

/Xam 'sorcerers' were feared and respected for their

unrealistically long, penises/emanations from the groin.

powers (Bleek & Lloyd 1911; Bleek n.d. 1935 & 1936).

Two have short, knobbed sticks in their raised hands that

Developing her account of the 'asymmetrical

might be dance rattles. The extreme right-har.d figure is

valuations of the genders', Solomon (1989; see also

depicted upside down and is about twice the size of thei

Parkington 1989) has argued that access to trance states

others; marked variation in size is a characteristic of many

rock paintings in the western Cape (cf. Yates et al. 1985:

and the ability to heal was largely male dominated.

Indeed, at least two scenes from the Koebee suggest that

fig. 3). A red line, now rather faded, is associated with the

predominantly men are depicted in the role of

predominantly

men are depicted in the role of

midriff of the inverted figure (see Lewis-Williams 1981b;

healerlshaman.

Dowson

1989).

,

U~~~owson

D.,-..,

., , ..

First, the three figures in Fig. 4 are part of a row of

In addition to such dance groups, several images in the

eight similar figures. All three are portrayed in postures

Koebee are of the kind that have been dascribed as

adoptedand

by dance

participants

that are sometimes adopted by dance participants that

in theare sometimes

"conceptual

visionary

forms translated into graphic

Kalahari (Lee 1967:32; Schadeberg & Hulme 1982).

representations" (Lewis-Williams 1981a:75). Figure 6, for

Similar postures can be seen in rock paintings throughout

example, depicts a reclining figure with a disprothe subcontinent (e.g. Stow 1930: plate 55; Lee &

portionately large arm connected by a thin red line to the

Woodhouse 1970:102 & 174; Lewis-Williams & Dowson

eared figure to the right (see also Fig. 10). The line seems

to emanate from the top of a very small hookhead. San

1989:39,42). The figures have long, thin necks, very

ethnography identifies this part of the body as the area

and

bulk

to

the

length

relative

and

short

arms

heads

small

from which shamans' spirits leave their bodies on out-ofof their torso, a 'distortion' that may be related to the

body travel (Marshall 1969:377; for /Xam accounts of

feelings of elongation !Kung healers say they experience

while in an altered state of consciousness (Lewis-Williams

out-of-body travel see Bleek 1935:23, 30-31, 1936:142

143). South of the Doring River, human figures connectedof

& Dowson 1989:77; Solomon 1989 associates elongation

by similar lines have been interpreted as representing out-travel

with masculinity). Several features, such as the lines

penises

travel

erect(Yates

(Ypaintings

the travel

theaof-body

'infibulation'), the

across the erect penises (so-called

'infibulation'),

of-body

et

el. 1985:78).(soecallred

~~~~~~~~~~~~~Healing

of

ano

iamls

/

/soemgtepc

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~healer/shaman.

~9S9).

~et

Vi~

\

v

Fig. 6. A set of image comprising a paint patch, or

'palette', and a small reclining figure connected by a

line to a larger therianthropic figure holding a whisk

in each hand. The images (see 'a' in Fig. 10) are part

a larger, confict scene and may depict out-of-body

as described in San ethnography. lhe paintings

eof

~~~~~~~~~~aacross

are proportionately fewer animal

in Maggs's (1967)

in Magga's (1967)

(1976)

wester

Cape sample and

Vinnicombe's

Drake

sites, all nsberg

three have certain patterns in

common Paintings of humans outnumber animals by

hu

woter

an

by

alm osmt ',5

i tho

,swe

Table 2 compares

Vfrnncesos ail

isp

recorded

,

Tn e K2b

c

ear

fr'q uenies

Ma

woa

im rn

p e sample and Vinnicombe's

MsgssD(6s erter

ape

e speaesVsombnate

numerically in all three samples. Paintings of eland and

nueily

i althe a m shalf of antelope depictions

hten

th Koetea Similar

a

ronortion prevail in the other two

te Koebe. Siil opotiontsreva

nt foth th f

sample Pitins of sa

to p

out or 4 %of

s

proporton very close

a

t

to that recorded by Maggw.

rm etr

aests(t

7

&Sealy983

table

e

1967:102; Maggs & Sealy 1983:44 table 1; Yates

al. 1985:73 & 79), the proportion of elephant paintings

in the Koebee is far higher than in the Drakensberg.

rded

the Koebee

paintings of felines were recorded in the Koebee

(see also Maggs 1967), although I was told of such a

p

asnowweaway

felties differentiates the two western Cape samples from

feline

.1_

n of te southern Drakensberapwhere 37

th ok aof teins wern recorded (Vr, h

mbe

r

recorded (income

p

1976:364).

A eature that seems to distinguish the Koebee from

Maggss (1967) western Cape sample is the high number

of fat-tailed sheep (see Manhire er al. 1986:22). Although

they occur at only three sites, afte smallantelope and

eland sheep are the most numerous category of animal

a fuarther 13 sheep-like

~~~~~~~~~~~~images

in the Koebee sample than

images in the Koebee sample than

^\

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Mag

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~No

South African Archaeological Bulletin

South African Archaeological Bulletin

and Bushmen' (Nienaber & Raper 1977:726,

1980:528-530). Nienaber and Raper (1980:530) suggest

that 'Koebee' be translated as 'place of fighting'

(oorlogsplek).

The presence of paintings of sheep in a dance scene

(Fig. 7) has apparently not hitherto been recorded in the

Cape (see Manhire et al. 1986:26 & 29) and

suggests that domestic stock had become increasingly

important conceptually and ritually to the San of this area.

In addition, a painting on the nearby Gifberg of a tall

figure pointing towards a sheep (Fig. 8) suggests that these

animals were implicated in San magical practices (see

Lewis-Williams & Dowson 1989:48 for a discussion of

Table 2. Frequencies of animal species depicted in rock art as recorded in samples from the western Cape and southern"Hottentots

Drakensberg.

KOEBEE 1 + 2

50 sites

COUNT

>riANIMAL

TYPE

27

78

105

Eland

Other antelope

Total antelope

Baboon

Elephant

Feline

11,0

31,7

42,7

16

14

0

6,5

5,7

0

10 6

10,6 26

0,4

2,4

12

W. CAPE

(MAGGS 1967)

46 sites

COU~INTr

DRAKENSBERG

(VINNICOMBE 1976)

150 ,ites

V6western

COUNT

80

136

216

18,6

31,6

50,2

848

1002

1850

8

40

0

5

49

5

37

7

0

1

17

1,9

9,3

0

1,.2

,

0

0,2

3,9

10

44

N/A

125

18

430

29,0

4,3

100

sIS

786

3606

26

~~~~~~~~~~~~Sheep

Warthog

Possible canine

possible equid

1

6

3

Unidentifiable

Other species

TOTAL

75

0

246

30,5

0

100

·

'- ~ ~': · ,f-":......

;- .*=';'..k~

;:~'%

-igure

a

.re^

.t...· 7 :=..~.

:r.

~.-

."^^"TK;*^

" ,:-|®' ~,~:

'

" '~ ~'^

','/~

''--"

-a-"

-,''-

;e .

'.-'

--

~?~Sla.a_:',

- -T

.^

~l~'t.-'^

.:5

,it'

^^

''

....

'."~.has -

. N

the'

. :-' ',.-5

". ,~:~,:

A

.

-

' ,iX.

i.

'Paint patches', or 'palettes', may be related to

smearing. They were noted at six sites from sample 1;

none was recorded from sample 2 . At two sites, patches

seem to be part of 'sets' of images (see Lewis-Williams

1992b for a definition and discussion of'sets') that include

depictions of humans in postures that signify al:ered states

of consciousness (see Fig. 6). Another group includes a

'palette', a kaross-clad figure, an ithyphallic figure and

:.

-

.

,.'^

,

...

"'

'e

-

."",.~

5

'*)

'.Fi..

...

,!.

-i ',,--.·-,~

.;

.reas

'~~~~~~~~~~

'Kobee'inkit o rlatonsips etwen he an nd tepantigs

heir right, centreou arguablysen.

7.Ft-tie

~ ~~~~~~~~t

presrvaion.

aining' suges

Teseep tha th Kobee

a arcored

furthsit butwerenot

animls wre

classified as such, owing to their incomplete state of

preservation). The sheep paintings suggest that the Koebee

artists were in close contact with people who kept

domestic stock, although the exact and no doubt changing

nature of this contact is unclear (see for example

-p

.

:

.*

"*

*'

.. "''

-all.

t

"

[..~--

..-

''

^^"^

.-. _

.'-:

'T:"'"

8 ...

Pantn

'

fro'' '"h Gieg .......

ng a'

:algr

fat-taldsep

mle ua

toad a"

,

-

'

..

A.

--'·

wthn'"yo"-eshe' bde....tig ae

sugstv of trnc stte., Te "-aopgus

pos-~~

-

^

1",.

"-~

',:"-.-/.^:-' ~,A:.^j:i

*.*:'--^s

.I:~'.--f' ,

".~'-r::

t^'a.-' 2

.~.:

*'".-,- .*': ".-.

.

re an

C~varin shade ofc~

r...

eitedcapig

'._,

.: :.ie.,, 'pinin

'

.rj'.'.

.

..

..

~.,; 1~. h figure

-C_~

Fig.

Fig.s7.Ft

in

e ts

c tale

entre ot ade soene Aimm

figoure at lower left is depicted in the 'arms-back'

posture suggestive of trance states. The steatopygous

women to its right are depicted clapping. The figure

',-_.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~:

?

-. '

.

:~::.

woe

oisrih

...

-.

,

~~ ~ ~

Paint Patches

-'~i·

.. \¶L"

.-.....

....

.

1,3

0,1

pointing). Commenting on paintings of sheep in Zimbabwe, Huffman has argued that the San considered them

1,0

potent because of their fatness: "sheep

Qparticularly

0,2

are not likely to be simple scenes of new people

,~~~~~~~~~~paintings

0,3

but complex statements about the control of potency"'

(Huffman 1983:51). Solomon (pers. comm.) suggests that

1,2

sheep were implicated in San fertility beliefs, and a

N/A

painting of a steatopygous woman and four fat818si 22,7qui~,Koebee

22,

tailed sheep could thus be interpreted as equating women

and sheep by virtue of their 'fatness'.

21,9

100

*..

.

· t-~~~~b&

23,5

27,8

51,3

recorded in sample 2. In total, some 67 images were

identified as smeared. I did not include paintings that

could have been affected by non-human factors, such as

water. With the exception of only two animal-like images,

all the smeared paintings are of human beings (see Fig. 9).

It appears that individual images and groups of images

were selected for this treatment; I did not encounter whole

panels that have been smeared. Yates &Manhire (1991:9)

have argued that smearing was a ritual practice peformed

either by the creators of the images, their contemporaries

or their descendants. It is, however, not clear what significance was attached to the practice.

.

thair

ediately

stestopygous, has a penis. Note the unpainted areasre

within many of the sheep's bodies. Paintings are in

varying shades of red and white.

Parkington et a). 1986; Smith et al. 1991; Schnire 1992).

Two of the many explanations for the Khsoekhoen name

'Koebee' link it to relationships between the San and the

Khoekhoen. One report suggests that San raided

Khoekhoen livestock and then retreated into the Koebee;

the other refers to the Koebee as a gathering place for

hat"hav

ben dlibrFig. b.cPainyingyfofmhethecisboseedhowtngCaetall avebee

pointing towards a fat-tailed sheep. A smaller human

are

pailn in

tog

the

eto

for

S ern adRpitngfinger

Smeared images, defined by Yates & Manhsire as

paintings that "have been deliberately obscured by

smearing of the pigment' (1991:3), are widespread in the

western Cape (see also Yates et al. 1990). Smeared images

were noted at eight Koebee sites in sample 1; none was

smears of paint. No instances of rubbing were

detected. Yates & Manhire (1991:4,8) noting that 'a great

many' of the patches observed in the Cederberg have 'been

rubbed, suggest that the patches form an integral part of

image assemblages and "that they were positioned within

compositions to be used ... in an interactive capacity'.

South African Archaeological Bulletin

South African Archaeological Bulletin

*

~~~

-%.~

~

~

~

~ %:2rr

~*%.f,~*-'

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~?:S

'I r

.v'

:.

. .

~~~,

r-.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~r

,~~~~~

'b:~~~~~~~~~~~~~anig

Rise

Fig. 9. Smeared figure. The image must have been

deliberately smeared, because the surrounding images

are relatively clear. A long penis or emanation fringed

Handprints

'Plain' and/or 'decorated' handprints were found at ten

of the sites recorded (see Manbire & Parkington 1983:32

for definitions and distributions in the western Cape of the

two types). They are relatively common in the western

Cape and in the Waterberg (north-western Transvaal); they

are much rarer in the south-eastern mountains (Van

Rijeses 1984;128).

Images

of Conflict

The striking painting shown in Fig. 10 seems to depict

a conflict or fight (it was first copied by Marjorie Hoehn

in the early 1960s). It draws together a number of the

themes I have discussed and points to the conceptual unity

of the Koebee art.

Conflict scenes in southern African rock art have often

been interpreted as literal records ofpart/cular events (see

Campbell 1986:256-257 for discussion). In many cases,

however, there are elements in the paintings that defy

literal interpretation (Campbell 1986; see also Yates er al.

1985:78 & figs lOa & lOb; Lewis-Williams & Dowson

1990:5-6 & fig. 2; Yates et al. 1990:52, for discussions of

the well-known Veg en vlug 'conflict' scene at Sevilla in

the western Cape). In the Koebee scene, two opposing

groups are depicted (Fig. 10). A group of eleven fairly

well preserved figures, nine of whom hold bows, are to

e ndwie

in

198:2)

with white dots can be seen on the left-hand figure,F.

who carries a quiver and is decorated with white paint.

Paintings in red and whitees

-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~heads;

the left; there is also a supine figure. This grotp faces a

larger group of 23 figures, at least eight of whom are

similarly holding bows (traces of a bow painted in white,

held by a ninth figure, can also be discerned). Eleven of

the 23 figures in the right hand group have hook-heads

while all eleven of those to the left have 'solid' r-eads.*Veg

The two groups appear to be focused around a large

and imposing figure with human feet and hands and animal

ears or horns, or, possibly, a headdress of some sort (Fig.

11; marked 'b' in Fig. 10). It is sitting and holding a staff.Frans

To its right a smaller 'eared' figure holds a tod. Three

similar figures are painted elsewhere at the site.

Immediately above the 'eared' figure is a sa:iall patch

of pigment which strongly resembles a small human figure

with what appear to be extremely elongated amd spindly

arms and legs that extend downwards over the large sitting

figure and end in an indistinct mass of pigment below

(Fig. 11). This may be another of the elongated bodies

associated with San curing dances,

Above and to the left of the 'eared' figure two figures

appear to be 'restraining' a third that is betveen them

(Fig. 12; marked 'c' in Fig. 10). A bow lies at their feet.

This group is similar to one in the Drakensberg that

Campbell (1986:260 & fig. 1A) suggests may refer to the

careful regulation of 'boiling' energy that has been

observed at !Kung healing dances (see Biesele 1978; Katz

1982 for discussion of the regulation of this energy).

Accounts of healing amongst the /Xam also refer to the

necessity of restraining medicine men and women, who

may enter a frenzy (Bleek 1935:2).

10. C

sn

A th

th tre he olid

lge

therianfl ic

. figure in

ha

ve solid

centre

theanthropic figure inthe

eleven of those to the right have hook-heads.

Images marked a, b and c are reproduced separately to

show greater detail. Red and white.

The images of out-of-body travel discussed above (see

Figs 6 & 10) also form part of the 'conflict scene'. The

themes of conflict and out-of-body experiences as depicted

in the panel seem to have been conceptually related - the

en Vlug' paintings also incorporate images of

anti this suggests that they are the product of a widespread

belief system.

and out-of-body

conflict travel - and suggest that such

fight scenes have deeper and more complex associations

than literal interpretations allow,

uys Wiese and Peter Rau first put me in touch with

local landowners. Messrs Botha and Basson generously

accommodated me and allowed me access to their land.

Kotze, Johannes Perrang, John Basson, Johnny

Phillips

the

and Boks and Van Zyl families guided me to

paintingsh Nic Swart spent weeks in the

field

with me,

His

and

debat

ing the images.

photographing

companionship and help in checking and redrawing the

tracings are gratefully acknowledged. Duncan Miller,

Shirley-Ann Pager and Thomas Dowson encouraged me to

write about the Koebee. David Lewis-Williams took an

active interest in my work and provided valuable feedback

whilst I was writing this report. I am grateful to Tony

Manhire and Royden Yates of SARU for showing me sites

on the Gifberg, especially the painting reproduced in Fig.

8. Anne Solomon kindly discussed aspects of her work

with me. Thanks to Godfrey and Marjorie Hoehn for the

opportunity to compare notes and redrawings, as well as to

Tony Humphreys and the two referees for their suggestions. Financial contributions were made by the late

Tatiana Dubrova and the Rock Art Research Unit of the

University of the Witwatersrand. The Rock Art Research

Unit is funded by the Centre for Science Development and

the University of the Witwatersrand.

Agreeing with numerous writers on southern African

rock art, art historian Nettleton (1984:67) notes 'that in

practically no reputable studies of so-called pre-literate art

has the art for art's sake motive been found to be valid for

the image making activities of so-called primitive peoples.

... In most of these societies making art is a ritual activity,

hedged around by sanctions and prohibitions and couched

in terms of conventional iconography and style." The Koebee paintings bear out this understanding. Smearing and

the so-called 'palettes' both suggest that paintings were

considered to be potent in their own right. Moreover, the

artists' concern with dancing and supernatural potency is

evidenced by the use of metaphors and symbols, many of

which have been linked to San experiences of altered states

of consciousness. Over and above these associations, the

art seems to have been implicated in the negotiation of

gender relations. The Koebee images therefore follow

conventions that obtain elsewhere on the sub-continent,

Acknowledgements

South African Archaeological Bulletin

k];(

> J \~~~~~~~~\ \*B

!1JbiHiI

~

~

~

3

^^B

l

«-r

~~~~~~paintings:

~~~~l^H^T~

(

~

I^R JH~~~~~~~~~~~~

^^^^®~~~,«*i-r

^BU^

(^^&

iB ^K

^ *{ \.*R

W~

^S''''-^^^^^^~~~~~~~~~'-(^ '1^RV^L.~~~

(BP*

*l».

"*<^'i'^^ ^^P^

~series

~~~~~~'Maggs,

~rock

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

/4^^^^fe'^~~~~~~~

rx}

s

IV.a^1?%^^®%'

*-~

,

S

''

*

~:~~~~~~~~~~

SManhire,

&»

'

^ f

P

~~~~~

-i~~~~'*i~~~~

IfS

*

',*

»l

^

1

y

,.intingHottentotica

WI~~~~~/~

1

-.

-..-

Fig. 12. Images of restraint (detail from Fig. 10), such as

this, may refer to the regulation of potency during

j.

hio

heln dancea Th babe shap in* th adso

atnai

t

tt

gr1cNettleton,

may-represfaen na

mide

would

probably;not

noticed

a reply had

idl Ir

probably

r~ not

pp have

have

oabeen

been

nru.·r~s

noticed

had tathe

the

paintings not been traced. A bow liea at the feet of the

paint

not

ing

been

s

traced.

A

bow

lies

the

feet

thesother

Humiddleys,

Aigure.JRedandB

wt.Nienaber,

middle figure.

Red and white.

Donng~River south-Research

·igradas

~e

.

ter

ofZigureabove.

Schadeberg, J. & Hulme, G. 1982. The Kalahari Bushmen

dance. London: Jurgmen Schadeberg.

Schrire, C. 1992. The archaeological identity of hunters

and herders at the Cape over the last 2000 years: a

critique. South African Archaeological Bulletin 47:62-

Fig.HufmNienaher,

lrsalrgrtis

extend·:

~~~~~~art

erd Afigre

ed

hunting and mating in Bushman thought. Ohio

University Papers in International Studies, Africa

7.

T.M. O'C. 1967. A quantitative analysis of the

art from a sample area in the western Cape. South

African Journal of Science 63:100-104.

Maggs, T.M. O'C. & Sealy, J. 1983. Elephants in boxes.

South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series

4:49-53.

l~'® &

^ Parkington, J.E. 1983. A distributional

A.H.

approach to the interpreaation of rock art in the southwestern Cape. South African Archaeological Society

~~~~~~~~',''~

~~~~~'"

M

'~~~~I~~~~ bt~~~~

4 =A,

^

-r

I

the veil: San rock paintings and the rock face. South

African Archaeological Bulletin 45:5-16.

Loubser, J. & den Hoed, P. 1991. Recording rock

some thoughts on methodology and

technique. Pictogram 4:1 1-15.

McCall, 1970. Wolf courts girl: the equivalence of

-,^^^^^^'^i,~~

E,-'.r

Parkington, J.E., Yates, R.J., Manhire, A.H. & Halkett,

D.J. 1986. The social impact of pastoralism in the

south-western Cape. Journal of Anthropological

.

/^|fr4-J^A^^l^C••

';

t Note

imbe

Fig. 11. Detail of Pig. 10, showing the large 'eared'

figure and a similar, smaller figure to its right. Note

the figure above the 'eared' figure's head; its limbs

extend downwards over the large sitting figure.

References

Biesele, M. 1978. Sapience and scarce resources:

communication systems of the !Kung and other

foragers. Social Science Information 17:921-947.

Bleek, D.F. n.d. Bushman charms. Historical Society of

South Africa. Leaflet 1.

Bleek, D.F. 1935. Beliefs and customs of the /Xam

Bushmen: Part VII. Sorcerors. Bantu Studies 9:1-47.

Bleek, D.F. 1936. Beliefs and customs of the /Xam

Bushmen: Part VIII. More about sorcerers and charms.

Bantu Studies 10:131-161.

Bleek, W.H.I. & Lloyd, L.C. 1911. Specimens of

Bushman folklore. London: George Allen &Company.

Campbell, C. 1986. Images of war: a problem in San rock

art research. World Archaeology 18:255-268.

Dowson, T.A. 1989. Dots and dashes: cracking the

entoptic code in Bushman rock paintings. South

African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 6:8484.

a,R .1 . Boilui

rnergy: omutyheai agh mong

of Zimbabwe. South African Archaeological

Society Goodwin Series 4:49-53.

Humphreys, A.J.B., Bredekamp,1991.

H.C. & Kotzee, F.

aaar!ung

CAmrde:har

othe

ardU of

erst

A painting

of a fully recured

bow from noth

the

Dorting River, south-western Cape. South African

Archaeological Bulletin 46:46-47.

Katz, R. 1982. Boiling energy: community healing among

the Kalahari !Kung. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

Lee, D.N. & Woodhouse, H.C. 1970. Art on the rocks of

southern Africa. Cape Town: Purnell.

Lee, R.B. 1967. Trance cure of the !Kung Biushmen.

Natural History 76:31-37.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1972. The syntax and function of

the Giant's Castle rock paintings. South African

Archaeological Bulletin 27:49-65.

Lewis-Williams, J. D. 1974. Superpositioning in a sample

of rock paintings from the Barkly East district. South

African Archaeological Bulletin 29:93-103.

Believing and seeing:

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1981a.

symbolic meanings in Southern San rock paintings.

New York: Academic Press.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1981b. The thin red line: southern

San notions and rock paintings of supernatural

potency. South African Archaeological Bulletin 36:513.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. 1992. Vision, power and dance: the

genesis of a southern African rock art panel.

Veertiende Kroon-Voordracht. Amsterdam: Stichting

Nederlands Museum voor Anthropologie en Praehistorie.

Archaeology 5:313-329.

64.

Smith, A.B., Sadr, K., Gribble, J. & Yates, R.

Excavations in the south-western Cape, South Africa,

and the archaeological identity of prehistoric huntergatherers within the last 2000 years. South African

Archaeological Bulletin 46:71-91.

Smits, L.G.A. 1971. The rock paintings of Lesotho, their

content and characteristics. South African Journal of

Science Special Issue 2:14-19.

Solomon, A.C. 1989. Division of the Earth: gender,

symbolism and the archaeology of the southern San.

Unpublished MA thesis. University of Cape Town.

Stow, G.W. 1930. Rock paintings in South Africa.

anhire,

A.H.

n gton i , M nt.E,azel,

A.D. & Magg,

Van Riet Lowe, C. 1956. The distributi

TM. aC. 1986. Cattle, sheep and horses: a review of

rock engravings and paintings in

Goodwin animals

Series art

4:29-33.

London: Methuen.Series 7. Pretoria:

A

ca.

Archaeological

Afriern

of south

in the rock

domestic

5:22-30.

Marshall, L. 1969. The medicine dance of the .'Kung

Bushm.ent. Africa 39:347-381.

image, function and meaning art:

rock

A. Sana

African

Archaeological

Willcox.

N'leon

el to. A.R.

AR

u mrsi:imge

ico South

Su untonad

fra

rhelgcl

eligwould

Bulletin 39:67-68.

at

of

Raper,

Toponymica

&

P.. 1977.G.S.

inbr

.

Rp,

A: H-Z. Pretoria. Human Sciences

Council.

Graz:

25

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A. 1989. Images of

rock

art.

Bushman

power:

understanding

Johannesburg: Southern Book Publishers.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. & Dowson, T.A. 1990. Through

IT-

)»~~~~'V*^&~~~~~~~~~~~~

ii\,i\

South African Archaeological Bulletin

G.S. & Raper, P.E. 1T980. Toponymica

Hottentotica B. Pretoria. Human Sciences Research

C ouncil.

Pager, H. 1971a. The rock art of the Ndedema Gorge and

neighbouring valleys, Natal Drakensberg. South

African Journal of Science Special Issue 2:27-33.

olonay:

ma g,Graz: oiv,

Pager,

H. 1971b. Ndedema.

Akademsiche

Druck. ald

conet

Pager. H. 1975. Stone age myth and magic.

Akademische Druck.

Parkington, I.E. 1989. Interpreting paintings without a

commentary:

meaning,

motive,

content

and

composition in the rock art of the western Cape.

Antiquity 63:13-26.

ofon

prehistoric

South Africa.

rchaeological

who painted what? South African Archaeological

Bulletin 39:125-1S29.

Vinnicombe, P. 1972. Myth, motive and selection in

southern

ro fia

African

ck

a rt.t Africa

utr

ok

fia 42:192-204.

21-04

Vinnicombe,

P.

1976.

People of the

elnnd.

A c

Pietermaritzburg: Nata U l

niversity

Press.

Yates, R.J., Golson, I. & Hall, M. 1985. Trance

performance: the rock art of Boontjieskloof and

Sevilla. South African Archaeological Bulletin 40:7080.

Yates, R., Parkington, J. & Manhire, T. 1990. Pictures

from the past - a history of the interpretation of rock

paintings and engravings of southern Africa.

Pietermaritzburg: Centaur Publications.

Yates, R. & Manhire, A. 1991. Shamanism and rock

paintings: aspects of the use of rock art in the southwestern

Cape,

South Africa.

South African

Archaeological Bulletin 46:3-1.

^