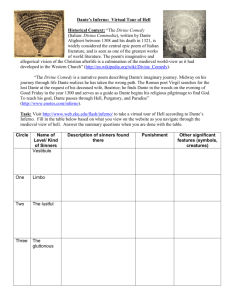

Introductions to The Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso

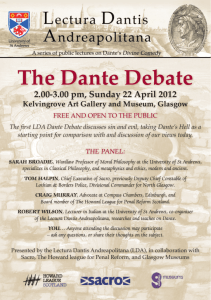

advertisement