Organic and Mechanistic departmental structures within a large

advertisement

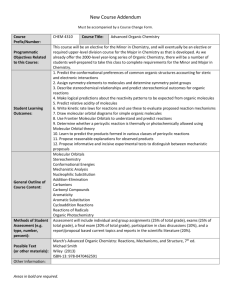

Organisational Structures And Vocational Training Provision A paper given at the Training and Learning Research Programme Conference, 16:30, Thursday 6th November 2000 by Brian Eyres (E-mail: brian.eyres@cibasc.com) BA(Hons) Open, PGCE(FAHE) MMU, MSc (Dist) Leicester Ciba Specialty Chemicals plc Background Tom Burns and Graham Stalker in their book The Management of Innovation (1961) (3rd Edition, 1994, Oxford University Press) developed and examined the concepts of Mechanistic and Organic characteristics using them to frame their analyses of organisational structures. Mechanistic characteristics were defined as being found where there are • hierarchical environments with central control functions • predominantly vertical communication channels, • high formalization and task/job definitions • and, to an extent, initiative mitigated by a rigidly defined command structure and positional terms of reference. Organic characteristics were those present • where organisational structure was more of a network, • where communications were more likely to be lateral • where task definitions are more fluid and flexible - related to competences and skills held rather than being a function of position in the organisation. • and where influencing of decisions were most likely to be made on the basis of expertise rather than an individual (or group’s) position in a command structure Considerably more points of contrast may be indicated such as • Authoritarian versus Democratic • Referential versus Empowered • Individual versus Group • Focused versus holistic approach • Internal rules as ‘law’ versus internal rules as guidance • Sometimes even a preference for qualifications gained within the organisation as opposed to those originating elsewhere despite the latter usually have a much wider currency and transferability. 1 Characteristic Task definition Communication Formalization Influence Control Mechanistic Rigid Vertical High Authority Centralized Organic Flexible Lateral Low Expertise Diverse The identification of these characteristics was intended to help to explain departmental functional behaviour in organisations and, indeed, this work has been developed, and used by other researchers over the years. However one area in which it would appear to have implications but which hitherto seems not to have been considered is where it impacts on training provision. In particular I’d like to talk briefly today about the usefulness of the model in examining the efficacy of vocational training in larger multi-departmental organisations. A useful way of approaching the model might be to view • • mechanistic features as those which encourage job/task-centred approaches to training, and organic features as those which focus more on the development of the individual. In my research, I examined the internal department structure of a multi-national chemical company and looked at the strength of the relationship found there between both mechanistic and organic departments and training provision. A questionnaire was sent to managers (i.e. the commissioners of training) at the company’s Manchester site to elicit answers which would allow the classification of departments as either organic or mechanistic. It went on to try to establish links between; • • • the department structures, forms of training found there, and whether they were successful and/or appropriate in meeting perceived needs of; ◊ ◊ ◊ individual trainees, department managers, and the company as a whole. The survey was extended to sites at Paisley in Scotland, then Grenzach, in southern Germany where similarities and differences were identified and discussed. 2 Though the sample was relatively small (120) an 85% response mitigated this to some extent and, after all, the cohort approached represented all those who were active in commissioning training within the company. Study Findings 1. Given that such environments do quantifiably exist, their characteristics may 2. 3. 4. 5. require the trainer to acknowledge the influence they may have on the organisation and delivery of effective, appropriate training. For example: • The trainer will be more effective if the training forms are congruent with the prevailing departmental type as trainees (and even more so where they are ‘qualified’ persons are undergoing ‘refresher’ training) will, wittingly or otherwise, identify with the training more and feel it to be more appropriate and relevant for them as its form and delivery accords with prevailing departmental philosophies and expected methods of working. (This certainly seemed to be the case with the departmental managers in the study.) If this is so it may well fundamentally question the rationale and suitability of a system of training being provided - and in some cases might help to explain its lack of efficacy. For example; • The progress and success of Vocational Qualifications in manufacturing settings which are predominantly mechanistic in orientation will be seriously compromised where the actual structure of the qualification is conceived and presented in organic terms. It was found that departments, with few notable exceptions, tended not to be extremes of type but have a preponderance of one set of characteristics or the other. What could be said from the study with a degree of certainty however was that mechanistic features tended to increase with proximity to the manufacturing process and decrease the further an area was situated from it. • In the example in the study then, this meant Production, Packaging and Warehousing areas were strongly mechanistic whilst IT and HRM/D were strongly organic. • Areas such as R&D proved to be more problematic and displayed both sets of characteristics at different levels of their internal organisation (i.e. Product development interacted mostly with Production and was highly mechanistic; on the other hand other research-driven areas did not and were organic in structure.) A example to reinforce the findings is that seen when desirable employment characteristics listed by the ‘organic’ HRM function were utilised to judge the suitability of prospective process operators for the ‘mechanistic’ Production departments. After the procedure was modified to include Production Team Leaders on the interview panels a greater proportion of new starters completed initial training successfully and were taken on permanently. One of the factors at work in this instance would seem to be the need for the presence of a more taskfocused approach, somebody who’d worked in production and so was used to the hierarchical power structures prevalent there. 3 6. As indicated by the previous point, real-world, in-service solutions are constantly having to be found and this research merely works towards demystifying the rationale behind such events. Managers could indeed (albeit unwittingly) generally categorise their departmental needs adequately and commission appropriate standards and complexions of training. In other words, training types were usually allocated appropriately. 7. Nevertheless there was found to be substantial inappropriate provision which, seen through the framework of this model, is a waste of finite and valuable time, money and resources. 8. To be cost effective, planning of vocational training provision needs to consider the organisational framework in which the training itself is taking place. In the context of the model sketched in this paper that may mean an evaluation of where it is likely to situate along the organic-mechanistic continuum. Further issues and questions for debate 1. Might organic training in mechanistic areas project an ethos of selfdetermination, decision-making potential and independent thought incompatible with the nature of departmental operations? 2. Might mechanistic training in organic areas seem didactic/behaviourist given that a learner’s usual environment has accustomed them to proximity to decision-making and independent action? 3. If these scenarios do exist, wouldn’t not taking their influence into account be detrimental to the construction and development of optimal workplace training environments in general not merely in specific cases? 4. More positively, might organic courses presented to workers from mechanistic areas enhance operations by liberating them from a mundane environment perhaps re-energising and motivating them? 5. How far can this go before it the tensions it may generate begin to start questioning (and ultimately compromising) the fundamental complexion of the department? 6. It’s absolutely crucial that where training is organised and facilitated for areas which have differing make-ups in mechanistic/organic terms, this is taken into account. What can often happen is that a training function/provider (most naturally at home in, and the product of, an organic environment) may tend to value and promote courses or training packages which reflect that particular orientational base. 4 Implications with reference to conference theme of “Raising attainment in authentic settings.” 1. There is a need to fully recognise, amongst employers, that vocational qualifications are not learning or training in themselves but merely the frameworks by which those processes might be appropriately structured. 2. Existing learning/training, especially in manufacturing, largely reflects departmental orientation in terms of mechanistic/ organic characteristics. 3. In the light of points 1 and 2, the efficacy of vocational qualifications in particular contexts (not just manufacturing, or even industrial) might be optimised by taking into account the structure of the organisational environment. i.e.; • • Vocational qualifications in mechanistic areas are probably more likely to be more effective if they are more prescriptive in their delivery as well as in their expectations. Similarly, those in organic areas might profit from a less prescriptive approach, which aims to be somewhat more consultative, inclusive and discursive. 4. To be optimally effective and to compliment particularly industrial learning and training strategies, vocational training must be flexible enough to be able to • emphasis qualities and attributes of learner-based (organic) approaches as the situation requires • emphasis qualities and attributes of function-based (mechanistic) approaches as the situation requires • do these things without the danger that the inherent tension this produces will pull the structure apart • still retain, and advocate as core, many elements of both approaches whichever way emphasis is shifted in particular cases. Further research The speaker is currently researching into vocational qualification initiatives in diverse Mechanistic and Organic environments to try to quantify 1. disruptive effects where there is a mismatch of training with the predominant organisation type, and 2. the benefits of being able to tailor training provision to harmonise with intrinsic organisational structures. 5 Some background reading in the area • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Aldag, Ramon J. and Ronald G Storey, “Environmental Uncertainty : Comments on Objective and Perceptual Indices,” pp.203-5 in Arthur G Bedeian, A. A. Armenakis, W. H. Holley Jr., and H. S. Field Jnr., (eds.) Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, (1975), Auburn, Alabama : Academy of Management. Burns, T. and Stalker, G. M., (1961), The Management of Innovation, Tavistock Publications Burns, T. and Stalker, G. M., (1994), The Management of Innovation, (3rd Edition), Oxford University Press CLMS, (1995), ‘Determinants of Training Activity within the Organisation’, Leicester. Crozier, Michel, (1965), The Bureaucratic Phenomenon, Oxford University Press Emery, Fred E. and Eric L. Trist, (1965), “The Causal Texture of Organizational Environments”, pp 21-32 in Human Relations, February, 1965 Handy, C. B., (1981) Understanding Organisations, 2nd edn., Harmondsworth : Penguin Hendry, C., (1991), ‘Corporate Strategy and Training’ in Stevens, J. and Mackay, R., (eds.), Training and Competitiveness, London : Kogan Paul Koontz, H. & Weihrich, H., (1990), ‘Basic Departmentation’, in Essentials of Management, Chapter 8, 5th edition, McGraw-Hill Lawrence, P. R. and Lorsch, J. W., (1967), Organization and Environment : Managing Differentiation and Integration, Boston : Div. of Research, Harvard Business School. Mintzberg, H. (1979), The Structuring of Organizations, Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice Hall Pettigrew, A. M., (1979), ‘On Studying Organizational Cultures’, Administration Science Quarterly, Volume 24, pp 570-581. Pettigrew, A. M., (1985), ‘Culture and politics in strategic decision-making and change’, in Pennings, J. M., (ed.), Organizational Strategy and Change, San Francisco : Jossey Bass Pettigrew, A. M., Jones, G. R. and Reason, P. W. (eds.) (1982), Training and Development Roles in their Organisational Settings, MSC. Taylor, F. W., (1911), The Principles of Scientific Management [Reprinted in Scientific Management, New York : Harper, 1947] Tosi, Henry L., Ramon J. Aldag and Ronald G. Storey, “On the Measurement of the Environment : An assessment of the Lawrence and Lorsch Environmental Subscale,” pp.27-36 in Administrative Science Quartlerly, March 1973 Woodward, Joan, (1962), Industrial Organization : Theory and Practice, London 6 Characteristics of Mechanistic and Organic Systems [collated from Burns and Stalker, The Management of Innovation (1961)] a) b) c) d) e) f) g) Mechanistic Specialised differentiation of functional tasks into which problems or tasks are broken down. Abstract nature of tasks pursued with techniques and purposes mostly distinct from those of the concern as a whole. Improvement of means pursued rather than accomplishment of company ends. Reconciliation, at each hierarchic level, of distinct performances by individuals or groups by their superiors who are in turn responsible for seeing each task is relevant in its own special part of main task. Precise definition of rights, obligations and technical methods attached to functional roles. Translation of rights, obligations, methods into responsibilities of functional positions. Hierarchic structure of control, authority and communication. a) b) The ‘realistic’ nature of an individual task which is seen as set by the total situation of the concern. c) Adjustment and continual redefinition of individual tasks through interaction with others. d) Shedding of ‘responsibility’ as a limited field of rights, obligations and methods. e) The spread of commitment to the concern beyond any technical definition. f) Network structure. Sanctions on conduct more from a presumed community of interest than contract relationship with a nonpersonal corporation represented by an immediate superior. Omniscience not imputed to the concern head. Technical, commercial knowledge and tasks may be sited anywhere in network. Location becomes ad hoc centre of authority and communication on the subject. g) Reinforcement of the hierarchic structure by location of knowledge of actualities exclusively at top of hierarchy where final reconciliation of distinct tasks and assessment of relevance made. 7 Organic Contributive nature of specialist knowledge and experience to the common tasks of the concern. h) i) j) k) Tendency for interaction between members of the concern to be vertical, i.e., Between superior and subordinate. Operations/working behaviour governed by instruction/decisions from superiors. Insistence on loyalty to the concern and obedience to superiors as a condition of acceptance. More importance/prestige attached to internal over general (cosmopolitan) knowledge, experience and skill. h) Lateral communication through the organisation between people of different rank. Consulting rather than command. i) Communication being information and advice rather than instructions and decisions. j) Commitment to the task and ‘technological ethos’ of progress and expansion at least as highly valued than loyalty or obedience. Importance/prestige given to affiliations /expertise valid in industrial, technical, commercial milieux external to firm. k) 8