Using A Learning Style Approach To Achieve Success On The CPA

advertisement

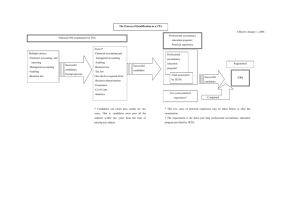

COV ERS T O RY Using A Learning Style Approach To Achieve Success On The CPA Exam by Dr. Greg Filbeck, CFA, FRM A s a CPA candidate, you should ask yourself two questions before beginning preparation for the CPA exam: Which learning or “sensory” system should I select to maximize my comprehension and retention? And, how can I best approach the material to match my learning style? Most candidates probably would not be surprised to learn of the variables, such as the number of hours spent studying and successful participation in a CPA review program, that are viewed as primary factors for CPA exam success. (Brahmasrene and Whitten, 2001, and Ashbaugh and Thompson, 1993). While this general information is helpful, what is the best way for YOU to be successful? Determining the way you learn best is a primary key to successful preparation for the CPA exam. Kaplan CPA Review starts with a very simple assumption: every candidate can pass the CPA exam once that person has identified his or her preferred learning style. Learning style research is not new. Previous research indicates that learning is most effective when a learner is: • Able to use life experiences to better understand principles (Dewey, 1938). • Actively engaged in the learning process (Lewin, 1951). • Matched with his or her psychological learning type (Piaget, 1971). 6 NEW ACCOUNTANT What is Your Primary Sensory System? Torres (1986) recognizes that people view the world through information that is filtered through three main sensory systems: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. In reality, most individuals learn best through a mixture of these systems. Kaplan recognizes that everyone learns in a different way and does not try to force everyone into a “one size fits all” program. Kaplan has used learning style research in developing a wide array of materials to meet the unique needs of each candidate. Your ability to identify the sensory system from which you tend to have maximum retention can be very helpful in your preparation efforts for the CPA exam. Visual sense includes retaining information presented as an image. Those operating primarily from this system can often be heard making remarks such as, “I can see what you’re saying” or “The idea is unclear.” Ask yourself the following questions to determine if visual sense may be the sensory system on which you rely: • Do I often visualize in my mind’s eye past examples of material I have learned? • Do I often find myself taking notes on a mental blackboard as someone speaks to me? Kaplan CPA offers Faculty-Assisted Video Courses, Lecture and Problem-Solving Videos in video CD format, flashcards, and Internet-based solutions that might appeal to you. For example, many visual learners prefer to carry flashcards with them wherever they go so that they can look at one question after another and then review each answer. These same candidates may prefer to watch a video presentation several times as a way of gaining comprehension for complex materials. Auditory sense includes talking (self talk) and hearing (active listening) and retaining information based on spoken words. Those operating primarily from this system can often be heard making remarks such as, “I hear what you’re saying” or “That’s music to my ears.” Ask yourself the following questions in order to determine if auditory sense may be the sensory system on which you rely: • Do I recall what others have said in the past through mental tape recordings? • Do I engage in internal dialogue? For this reason, many CPA candidates prefer to be in a Kaplan Faculty-Assisted Video Course where a concept is presented on a screen or board and then orally explained by a teacher. That oral explanation simply “makes the pieces come together” for them. In addition, Kaplan offers Audio Retention CDs where an essential question is asked, a pause of a few seconds is provided, and an answer is explained. Over the years, many delighted candidates have said, “I didn’t even realize that I was an auditory learner until I started listening to your Audio Retention CDs!” Kaplan CPA Lecture and ProblemSolving Videos are a natural choice for visual and auditory learners. Kinesthetic sense includes the use of touch, taste, and smell. Those operating primarily from this system can often be heard making remarks such as, “I’ll get in touch with you” or “I want a grasp of the facts.” Ask yourself the following questions in order to determine if kinesthetic sense may be the sensory system on which you rely: • Do I have strong internal feelings about information I receive? • Do I respond to hands-on opportunities to learn? For this type of learner, Kaplan CPA offers Internet-based questions and solutions that fit your learning style. The ability to read a question and click on a correct answer is a strong kinesthetic learning tool used by many successful candidates. Kinesthetic learners will appreciate the hands-on approach of an interactive online learning environment. Hopefully, you have a better idea of the sensory system on which you rely most. What’s your learning style? It is not that one style is good and the rest are bad or that one is superior and the rest are inferior. The key is to come to understand the style or styles that are most efficient for you. Kaplan provides study guides, true-false questions, Faculty-Assisted Video Courses, Internet-based programs, exam-like problems, Audio Retention CDs, and simulations because we want to help you develop the program that suits your needs. What’s Your Learning Style? How can you learn about your own particular learning style? A variety of learning style inventories exist in order to test alternative hypotheses of learning effectiveness, including Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory, Dunn’s Learning Style Inventory, the 4MAT, and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Of the four, the MBTI has been used extensively to examine the relationship between learning styles and performance (Campbell and David [1990], Eggins [1979], Geary and Rooney [1993], Keirsey and Bates [1978], Lawrence [1984, 1994], McCaulley [1976], Myers [1979, 1980], Myers and McCaulley [1989], and Schroeder [1993]). The MBTI is the most widely used instrument in business, education, and counselling for assessing personality variations in mentally healthy individuals and is commonly used to better understand learner performance issues. The MBTI is based on earlier work by Carl Jung and was developed, tested, and then modified for over 40 years by Briggs and Myers. The popularity of the MBTI as a diagnostic assessment instrument has increased dramatically over the past 20 years with well over two million participants in the last year alone. Over 1,000 publications exist concerning the MBTI. It has been used in areas as diverse as career NewAccountantUSA.com 7 Dimensions Measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Preferences for focusing attention Preferences for acquiring information Preferences for making decisions Preferences for orientation to the outer world Extraversion (E) – Individuals focus attention on the outer world of people and things. They draw energy from interacting and being engaged and so learn most effectively when they are engaged in activity. Sensing (S) – Individuals focus on the concrete aspects of a situation and value what can be seen, touched, felt, smelled, or heard. They tend to be practical minded, concerned with details and facts, and have greater acceptance of what is given. Thinking (T) – Individuals focus on objective decision making based on a desire for fairness. They seek logic in their analysis of situations to achieve objectivity. They prefer to discover what may be wrong in situations that arise and are more likely to offer critical feedback. Judging (J) – Individuals focus on leading a life that is organized and orderly, seek closure, prefer control over their lives, and plan accordingly. Source: Filbeck and Smith (1996) and marital counselling to uncover work style strengths. Four dimensions are measured by the MBTI. • The first dimension represents the process by which participants are energized to generate ideas and gather information—extraversion (E) versus introversion (I). • A second dimension investigates how participants process information—sensing (S) versus intuition (N). 8 NEW ACCOUNTANT Introversion (I) – Individuals focus attention on their inner world. They draw energy from internal reflection and so learn best through reflecting and understanding the context of a problem before being engaged. Intuition (N) – Individuals focus on the abstract and value relationships not immediately recognizable to the physical senses. They strive to understand the “big picture” and are interested in change and future possibilities. Feeling (F) – Individuals focus on subjective decision making based on a desire for harmony. They consider impacts on people in their analysis. They prefer to affirm what is right with situations, and are more likely to offer appreciation and sympathy. Perceiving (P) – Individuals focus on leading a life that is flexible and spontaneous; they seek to keep decisions open and prefer to adapt to situations rather than control them. • A third dimension assesses how participants make decisions— thinking (T) versus feeling (F). • The fourth dimension measures their orientation to the environment—judgment (J) versus perception (P). Read through the following pairs for each of the four dimensions and determine which you feel is most like you. Once again, be as honest as you can; there are no right or wrong answers. The breakdown in the general population by dimension is approximately 75% extraverted (E), 25% introverted (I); 75% sensing (S), 25% intuitive (N); 50% thinking (T), 50% feeling (F); 55% judging (J), 45% perceiving (P). There is no differentiation based on gender, with the exception of the thinking/feeling dimensions, where approximately two-thirds of males prefer thinking and two-thirds of females prefer feeling (Myers and McCaulley, 1989). From these four dimensions, 16 possible combinations of MBTI What’s My Preference for Focusing Attention? Extraversion (E) Strategies Introversion (I) Interacting with classmates Focusing on individual study Learning by talking Motivating self through personal achievement Use of active experimentation Relying on lecture-based instruction What’s My Preference for Acquiring Information? Sensing (S) Intuition (N) Preferring lecture orientation, including stepby-step methods leading to the “big picture” Preferring innovative and unusual ways of learning, starting with an overview followed by a breakdown in steps Use of visual aids and props Use of imagination Incorporating practical hands-on examples Incorporating holistic linkages of material Strategies preferences exist. The combination of preferences results in individuals emerging in one of 16 possible combinations: ISTJ ISFJ INFJ INTJ ISFP INFP INTP ISTP to explain differences in performance on various test question formats on accounting examinations. They utilize Kolb’s learning style inventory (LSI) and data on the student’s sex, age, and accounting GPA. Their findings indicate that a learning style ESTP ESFP ENFP ENTP variable was significant for three of ESFJ ENFJ ENTJ ESTJ four testing formats. Previous research indicates that the two most common An individual whose preferences types found in the CPA population indicate a combination of ENFP, for are ISTJ and ESTJ (Satava, 1996, example, would tend to draw energy 1997). This result matches closely from external forces (E); process with research indicating that the most information based on possibilities common types among accounting and hunches (N); make decisions professionals are ISTJ, ESTJ, and based on values and feelings (F); INTJ (Jacoby, 1981, Kreiser, McKeon and prefer a flexible, adaptive and Post, 1990; Schloemer and environment (P). While sharing Schloemer, 1997; Shackleton, 1980). basic personality characteristics, So, after this discussion, let’s assume two individuals with the same type that you have a good indication of may vary widely in their application what your four-letter MBTI type because of life experiences, might be. How can you use this maturation, and environment. information to prepare for the CPA Holley and Jenkins (1993) exam in an optimal way to maximize construct a multiple regression model your learning style? Let’s explore each of the four dimensions of the MBTI complete with strategies for success for the CPA exam. Students preferring introversion tend to prefer classes that are primarily lecture-oriented, focus on linkages among materials across the entire course, and prefer personal achievement rather than group cooperation. Extraverts consistently prefer interactive learning, whereas introverts prefer learning environments that do not involve significant interaction. Extraverts will thrive in the group learning environment provided by the Kaplan CPA Faculty-Assisted Video Course. This dimension is the single most important one to consider when a learner establishes a study program for the CPA exam. Learners who have a sensing preference tend to prefer classes that are lecture-oriented and NewAccountantUSA.com 9 What’s My Preference for Making Decisions? Thinking Strategies Feeling Trust perceptions of hidden patterns among distracting stimuli Focus on holistic learning Solicit critical feedback for improvement Reward self for study milestones achieved Use of competition Use of collaboration What’s My Preference for Orientation to the Outer World? Judgement Strategies Perception Establish a schedule of topics to be covered with deadlines Establish a tentative plan to ensure all material is covered Organize study efforts into a syllabus Allow for open exploration of topical coverage Use drills and teaching games for motivation Focus on tactical learning opportunities classes that focus on one assignment or project at a time. Candidates with the sensing preference can maximize their study efforts by selecting step-by-step methods that facilitate accomplishing tasks at hand by explaining the steps that lead to logical leaps in reasoning and by using visual aids and props when available. When theory and concepts are more important than supporting details, candidates take appropriate notes and master the material accordingly. Sensing candidates should be encouraged to mix abstract thought and theory with concrete details and to make connections, see patterns, identify trends, think creatively, and consider why things happen the way they do. They should be increasingly exposed to and encouraged to consider complexities and ambiguities. In contrast, individuals preferring intuition as a means of collecting 10 NEW ACCOUNTANT information would rather see the overview of a chapter before the actual presentation and use innovative and unusual methods for completing assignments. Intuitive candidates learn best by analysing connections, patterns, and trends rather than by manipulating data or memorizing facts. When facts and details are critical, intuitive students should take appropriate notes and master the material accordingly. Students with the sensing preference learn new material best by going from concrete to abstract, while intuitive students learn new material best by going from abstract to concrete. The same material can meet both needs by initially presenting an overview of new material, then focusing on the concrete applications, subsequently providing the theory, and then focusing once again on concrete applications—including connections with overall course material. The sensing disposition of most accounting students causes them to gravitate towards concrete and sequential learning methods. Individuals with a thinking preference prefer critical feedback on how to improve. They perceive themselves as being good at ignoring distractions, concentrating while studying, and organizing their study time well in advance (Filbeck and Webb, 2000). Those with the feeling preference desire friendliness and the ability to ask questions when opportunities arise in live classrooms. This is accomplished by providing students with the opportunity for substantial interaction in each class period (which is a pedagogy that is preferred regardless of type). This interaction focuses on the impacts particular policies can have on various organizations and involves participants relating their personal experiences. Candidates with a preference for judging as an orientation to the outer world prefer to have—well in advance—a schedule of topics to be covered and deadlines for assignments, in order to organize their study time in advance, and time to compose questions when opportunities arise. Those with the judging preference can best meet their needs by developing a syllabus for instruction with at least approximate dates for covering material. Judging students also prefer to work on only one topic at a time, and they benefit from specific guidelines for assignments. The smaller perceiving group prefers open exploration of material without a preplanned structure; does not organize studies well in advance; and, probably for that reason, works best under the pressure of a deadline. Setting periodic deadlines may be desirable in order to ensure that perceiving candidates do not fall behind. REFERENCES The Kaplan Activity Planner (KAP) provides judgement-oriented candidates with the self-assurance of a solid plan. Perceiving candidates will value the flexibility of this customizable study planner that keeps them on track. Now that you are familiar with each learning style and sensory system, ask yourself again the two previous questions before you begin your preparation for the CPA exam. Which learning system should I select? How can I best approach the material to match that learning style? Identifying your sensory system and learning style can be a tremendous aid as you prepare for the CPA exam. Take time to understand your strengths and develop an effective learning strategy based on a review program tailored around your strong points. Kaplan’s CPA Review products allow you to choose the study methods that best fit your individual style. Not only do Kaplan’s CPA Review products allow you to maximize your retention using your learning style, they are also designed to provide the convenience and flexibility you need to make exam preparation a part of your busy lifestyle. Without an effective learning strategy, preparing for the CPA exam can be an overwhelming task. Partner with Kaplan to give you a targeted learning approach and help you begin to enjoy a successful CPA exam review experience. For more information, visit www. kaplanCPAreview.com or call 1-800CPA-2DAY. Thanks to Joe Hoyle for his feedback and suggestions. Jacoby, P.F., 1981, “Psychological Types and Career Success in the Accounting Profession,” Research in Psychological Type, 4, 24-37. Myers, Isabel and Mary McCaulley, 1989, Manual: A Guide to the Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychological Press. Keirsey, David and Marilyn Bates, 1978, Please Understand Me, Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis Books. Nardi, Dario, 2001, Multiple Intelligences and Personality Type, Telos Publications: Huntington Beach, California. Brahmasrene, Tantatape and Donna Whitten, 2001, “Assessing Success on the Uniform CPA Exam: A Logit Approach.” September/October, 45-50. Kolb, David, 1985, The Learning Style Inventory, 2nd Edition, Boston, McBer. Piaget, Jean, 1971, Psychology and Epistemology, Middlesex, England, Penguin Books. Campbell, Dennis and Carl Davis, 1990, “Combining Critical Thinking Skills with Psychological Type,” Journal for Excellence in College Teaching, 1, 39-51. Kreiser, L., J. M. McKeon, Jr., and A. Post, 1990, “A Personality Profile of CPAs in Public Practice, The Ohio CPA Journal, Winter, 29-34. Satava, D., 1996, “Personality Types of CPAs: National versus Local Firms,” Journal of Psychological Type, 36, 36-41. Dewey, John, 1938, Experience and Education, New York, MacMillan. Lawrence, Gordon, 1984, “A Synthesis of Learning Style Research Involving the MBTI,” Journal of Psychological Type, 8, 35-41. Eggins, J.A., 1979, The Interaction Between Structure in Learning Materials and the Personality Type of Learners, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Indiana University. Lawrence, Gordon, 1994, People Types and Tiger Stripes, Gainsville, FL, Center For Application for Psychological Type, 3rd Edition. Filbeck, Greg and Linda Smith, 1996, “Learning Styles, Teaching Strategies, and Predictors of Success for Students in Corporate Finance,” Financial Practice and Education, 6 (1, Spring/ Summer), 74-85. Lewin, Kurt, 1951, Field Theory in Social Sciences, New York, Harper and Row Publishers. Ashbaugh, Donald and A. Frank Thompson, 1993, “Factors Distinguishing Exceptional Performance on the Uniform CPA Exam,” July/August, 68 (6), 334-337. Filbeck, Greg and Shelly Webb, 2000, “Executive MBA Education: Using Learning Styles for Successful Teaching Strategies,” Financial Practice and Education, 10 (1), 205-215. Geary, William and Cynthia Rooney, 1993, “Designing Accounting Education to Achieve Balanced Intellectual Development,” Issues in Accounting Education, 8 (1, Spring), 60-70. Satava, D., 1997, “Extraverts or Introverts: Who Supervises the Most CPA Staff Members,” Journal of Psychological Type, 43, 40-43. Schloemer, P.G., and M.S. Schloemer, 1997, “The Personality Types and Preferences of CPA Firm Professionals: An Analysis of Charges in the Profession,” Accounting Horizons, December, 24-39. Schroeder, Charles C., 1993, “New Students - New Learning Styles,” Change, (September/October), 21-26. McCaulley, Mary, 1976, The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Teaching Learning Process, Gainsville, FL, Center for Application of Psychological Type. Shackleton, V., 1980, “The Accountant Stereotype: Myth or Reality,” Accountancy, November, 122-123. Myers, Isabel, 1979, Type and Teamwork, Gainsville, FL, Center for Application of Psychological Type. Torres, C., 1986, “The Language System Diagnostic Instrument.” The 1986 Annual: Developing Human Resources, 99-103. Myers, Isabel, 1980, Gifts Differing, Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychological Press. NewAccountantUSA.com 11