Discrimination and the McDonnell Douglas

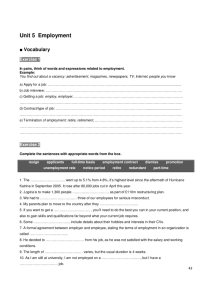

advertisement

John F. Myers, Attorney at Law Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 makes it illegal for an employer to discriminate in the workplace on basis of race, sex, national origin religion, origin, religion or national origin origin. In McDonnell Douglas v. v Green, 411 U U.S. S 792 (1973) the Supreme Court set forth a model in which an employee may prove workplace discrimination through the use of circumstantial/indirect evidence. [T]he critical issue before us concerns the order off prooff in d and d allocation ll ti i a private, i t non-class action challenging employment g g of Title VII discrimination. The language makes plain the purpose of Congress to assure equality of employment opportunities and to eliminate those discriminatory practices and devices which have fostered racially stratified job environments to the di d i i citizens. ii G i disadvantage off minority Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429 (1971). As noted in Griggs, supra: Congress did not intend by Title VII, however, to guarantee a job to every person regardless of qualifications. In short, the Act does not command that any person be hired simply i l b because h he was formerly f l the th subject bj t off discrimination, or because he is a member of a minority group. Discriminatory preference for any group, minority or majority, is precisely and only what Congress has proscribed. b d What h is required db by C Congress is the h removall off artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers to employment when the barriers operate invidiously to discriminate on the basis of racial or other impermissible p classification. Id. at 430-431. There are societal, as well as personal, interests on both The b h sides id off this hi equation. i Th broad, b d overriding interest, shared by employer, employee, and consumer, is efficient and trustworthy workmanship assured through fair and racially neutral employment and personnel decisions In the implementation of such decisions. decisions, it is abundantly clear that Title VII tolerates no racial discrimination,, subtle or otherwise.Id. at 430-431. (Emphasis added.) McDonnell Douglas, Id. at 800-801. Disparate Impact Does the employer use a particular employment practice that has a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin? For example, if an employer requires that all applicants pass a physical agility test, does the test disproportionately screen out women? Determining whether a test or other selection procedure has a disparate impact on a particular group ordinarily requires a statistical analysis. If the selection procedure has a disparate impact based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, can the employer show that the selection procedure is job-related and consistent with business necessity? An employer can meet this standard by showing that it is necessary to the safe and efficient performance of the job. The challenged policy or practice ti should h ld th therefore f b be associated i t d with ith th the skills kill needed d d tto perform f the job successfully. In contrast to a general measurement of applicants’ or employees’ skills, the challenged policy or practice must evaluate an individual’s skills as related to the particular job in question. If the employer shows that the selection procedure is job-related and consistent with business necessity, necessity can the person challenging the selection procedure demonstrate that there is a less discriminatory alternative available? For example, is another test available that would be equally effective in predicting job performance but would not disproportionately exclude the protected group? Title VII prohibits intentional discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. For example, Title VII forbids a covered employer from testing the reading ability of African American applicants or employees but not testing the reading ability of their white counterparts. This is called disparate treatment” treatment discrimination. discrimination Disparate treatment “disparate cases typically involve the following issues: Were people of a different race, color, religion, sex, or national origin treated differently? Is there any evidence of bias, such as discriminatory statements? What is the employer’s reason for the difference in treatment? Does the evidence show that the employer’s employer s reason for the difference in treatment is untrue, and that the real reason for the different treatment is race, color, religion, sex, or national origin? Simply stated, stated the McDonnell Douglas test provides: A plaintiff must first establish a prima facie case by a preponderance of the evidence, i.e. allege f t that facts th t are adequate d t to t supportt a legal l l claim. l i The burden of p production shifts to the employer, p y , to rebut this prima facie case by "articulating some legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for the employee’s employee s rejection. The employee may prevail only if he can show th l ’ response iis merely l a pretext t t thatt th the employer’s for behavior actually motivated by discrimination. (1) she was a member of a protected class; (2) she suffered an adverse employment action; (3) she was qualified for the position she lost; and (4) she was replaced p by y someone outside the p protected class,, or that "a comparable non-protected person was treated better." McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. at 802. Once the employee establishes a prima facie case of discrimination by a preponderance of the evidence, a rebuttable presumption of discrimination exists exists. See, See Tex. Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 254 (1981). (The rebuttable presumption is justified because if a p prima facie case is demonstrated,, the most likely and legitimate reasons for terminating an employee are eliminated.) "The burden of establishing a prima facie case of disparate treatment is not onerous." Burdine, 450 U.S. at 253. Establishment of a prima facie case creates an inference that the employer acted with discriminatory intent. Id. at 254. The employer must also articulate reasons that are clear and specific enough to give the employee a fair opportunity to respond to the third step in McDonnell Douglas framework. McDonnell Douglas, id., at 803. . In Tex. Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 253 the Supreme p Court held that once the employer p y produced admissible evidence of the reasons for the adverse action taken against the employee, the prima facie case is rebutted. Id., at 255. This burden of production is satisfied when the employer’s proffered reason “raises a genuine issue of fact as to whether it discriminated against the employee.” employee. Id., at 254. The employee must be given a full and fair opportunity to demonstrate by competent evidence that the presumptively valid reasons for the adverse employment action were, in fact, a cover-up for a discriminatory discrimination. McDonnell Douglas at 805. 805 “A plaintiff’s prima facie case, combined with sufficient evidence that the employer employer’s s asserted justification is false, may permit the trier of fact to conclude that the employer unlawfully discriminated.” Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Prods., Inc., 528 U.S. 133, 148 (2000) (2000). The employee does not have to produce additional evidence beyond the prima facie case and credible pretext evidence to sustain a finding of discrimination. Id., at 148. Demonstrate that employees, not within his protected class status, involved in conduct of comparable seriousness were nevertheless not disciplined or retained. The correct inquiry in determining whether a defendant's reason is pretextual is to determine if the employer "in fact fired [the employee] for this reason reason." Jackson v v. RKO Bottlers of Toledo, Inc. (6th Cir.1984), 743 F.2d 370, 378 cert. denied, 478 U.S. 1006, 106 S.Ct. 3298, 92 L.Ed.2d 712 (1986). Pretext is shown when the plaintiff establishes that the employer's proffered reason for the discharge simply is not worthy of belief. Texas Dept. Community Services v. Burdine,(1981), 450 U.S. 248, 256, (1981); Kline v. Tennessee Valley Authority, ( 6th Cir. 1997), 128 F.3d 337,342-343. In Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Products, Inc., 120 S. Ct. 2097 (2000) (Syllabus 1), the U.S. Supreme Court held that proof that an employer's explanation for a challenged job action is "unworthy of credence" is one form of circumstantial evidence of i intentional i l di discrimination i i i that h ""can b be quite i persuasive." i " In appropriate circumstances, the trier of fact can reasonably y of the explanation p that the employer p y is infer from the falsity dissembling to cover up a discriminatory purpose. Such an inference is consistent with the general principle of evidence law that the fact finder is entitled to consider a party's dishonesty about a material fact as "affirmative evidence of guilt." Id. at 2108 (internal (i l citations i i omitted). i d) In drawing such inference, the fact finder must be able to of the evidence,, that conclude,, based on a preponderance p p discrimination was a determinative factor in the employer's actions; simply disbelieving the employer is insufficient. Id. at 146-47. If an employer takes an adverse employment action against an employee for a discriminatory reason and later discovers a legitimate reason which it can prove would have led it to take the same action, the employer is still liable for the discrimination, but the relief li f that h the h employee l can recover may be b limited. li i d McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co., 513 U.S. 352 (1995). In general, the employee is not entitled to reinstatement or front pay, and the back pay liability period is limited to the time between the occurrence of the discriminatory act and the date the misconduct justifying the job action is discovered. McKennon, 513 U.S. at 361-62. When direct evidence of discriminatory bias, motive or animus is presented by a Plaintiff the defendant must prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that it would have taken the same action even if (Plaintiff) were not a member of a protected class. Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins p , 490 U.S. 228 ((1989). ) Under the "mixed motive" analysis, in a direct evidence case, case the plaintiff need not show that the unlawful reason was the only reason for the action. Plaintiff need only show that his or her protected class status was a motivating factor in the employer’s employer s decision to discipline and discharge, even if not the most important factor motivating the firing. The plaintiff in a disparate treatment case need only prove that membership in a protected class was a motivating factor in the employment decision, not that it was the sole factor. If the employer proves that it had another reason for its actions and it would have made the same decision without the discriminatory factor, it may avoid liability for monetary damages, reinstatement or promotion. The court may still grant the plaintiff declaratory relief relief, injunctive relief relief, and attorneys' attorneys fees and costs. 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g)(2)(B)(i). Direct evidence of discrimination is not required for a plaintiff to obtain a mixed mixed-motive motive jury instruction under Title VII VII. The starting point for this Court's analysis is the statutory text. See Connecticut Nat. Bankv. Germain, 503 U.S. 249, 253-254. Where, as here, the statute's words are unambiguous, the judicial inquiry is complete complete. Id Id., at 254 254. Section 2000e-2(m) 2000e 2(m) unambiguously states that a plaintiff need only demonstrate that an employer used a forbidden consideration with respect to any employment practice. Desert Palace, Inc. v. Costa, 539 U.S. 90 (2003)