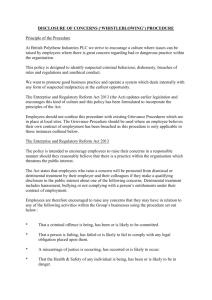

Australian Open Disclosure Framework

advertisement