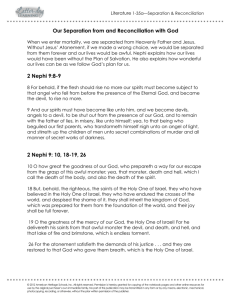

2 Nephi 2 Seminar - Mormon Theology Seminar

advertisement